The thought that most photographers working today will no longer, or will never, step foot in a traditional analog darkroom is remarkable for me. So much of the public imagination historically (and cinematically) with “photography” has been tied to the image of a man or woman hunched over trays of liquid watching an image appear on paper while enshrouded by the warm, amber glow of a safelight. Will that collective image ever be replaced with one of someone sliding a cursor along a histogram while bathed in the cool glow of a Macintosh monitor? Adam Bartos’s new book from Steidl Darkroom sheds some white light on the dying craft of analog printmaking and the environments that have produced most of the medium’s greatest images.

Bartos is a photographer of the generation where working in a darkroom was a natural extension of the artist’s process and although I suspected this book to be a kind of lament to their near extinction, Bartos himself has been making digital prints of his work for over a decade.

“I’ve never thought that spending time in a darkroom makes for a better (or worse) photographer. That’s a matter of choice and process…The difference might be that I make distinctions about prints because I have a feeling for them as objects with history. Those of us who have spent time in darkrooms may be more likely to share that experience, but I hope that photographers who haven’t will be interested in what the possibilities of printmaking are before thoughtlessly accepting the standard product. It’s quite easy to make a digital print that looks alright, but it’s still very difficult to make one that is beautiful and expressive.”

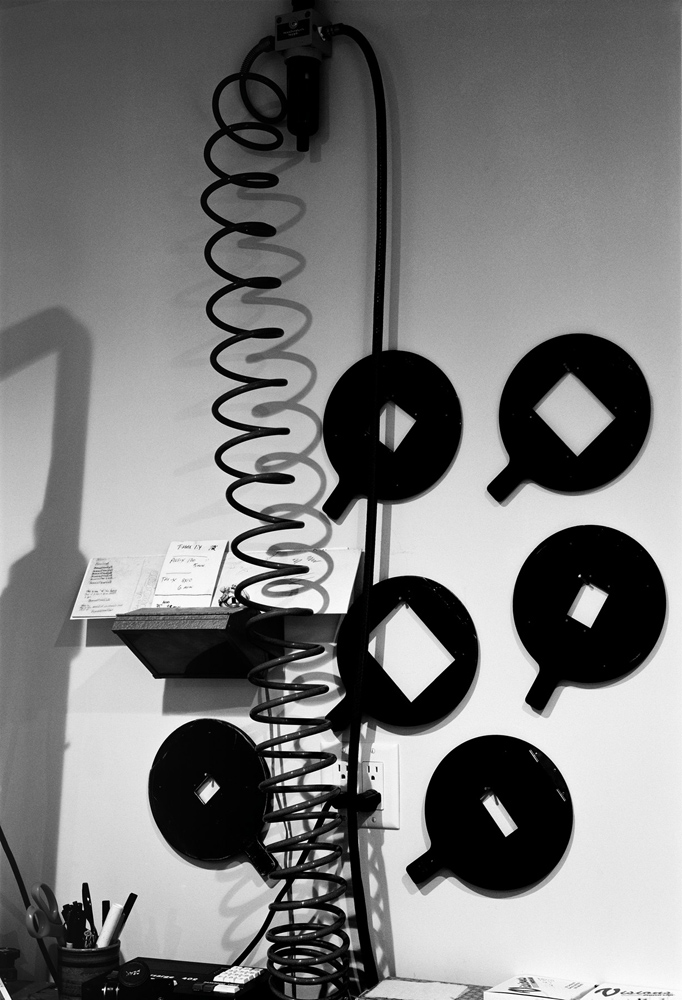

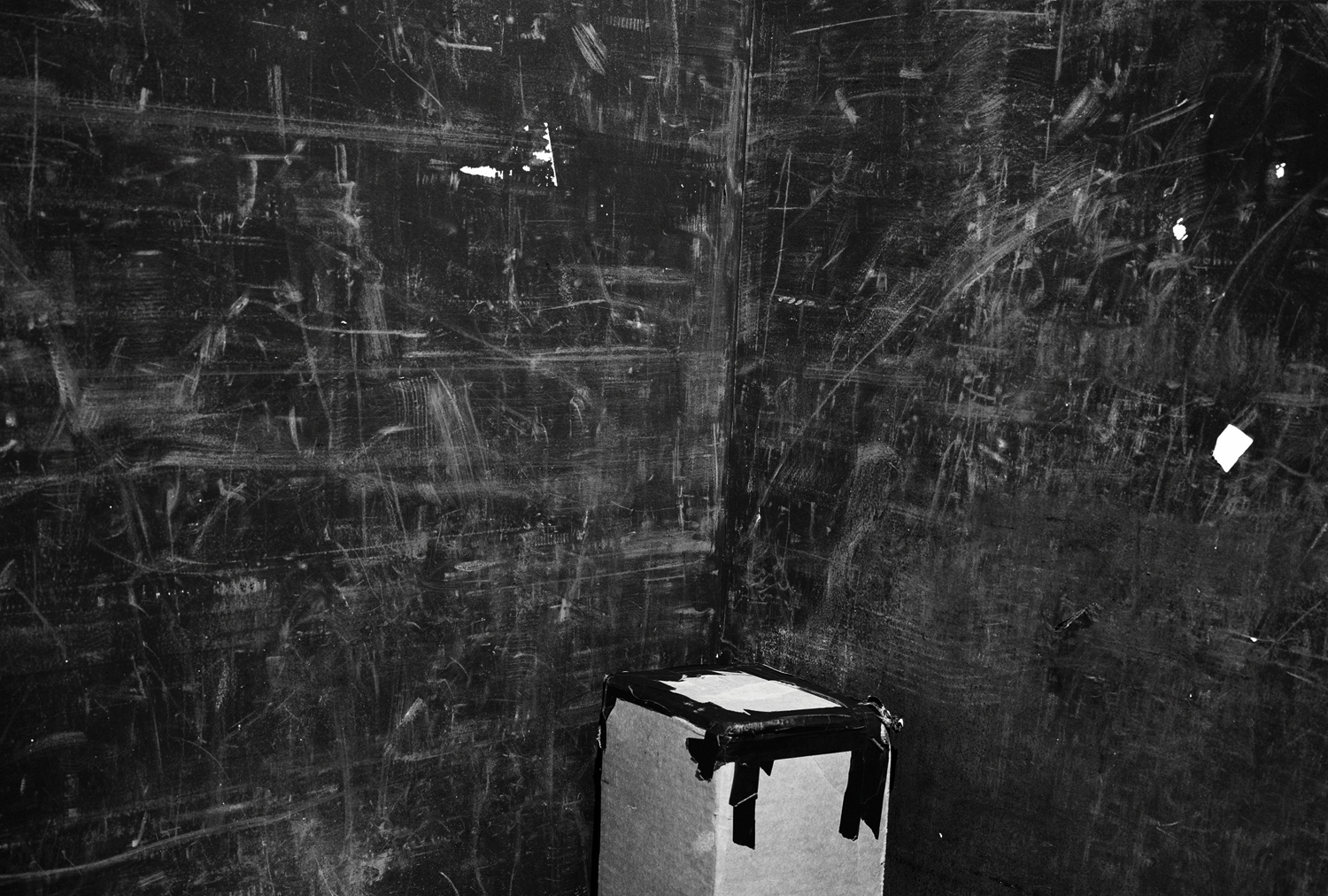

Bartos’s still-lifes describe how darkrooms are part laboratory and part personal spaces – lived in and decorated with talismans; a ball compass hangs from a safelight fixture, old test prints and penciled notations are left pinned to walls, layers of dust coat unused equipment. (I recall reading a story about the American photographer Garry Winogrand and his darkroom enlarger upon which hung several items including an old bow-tie and a string of rosary beads. When asked about these things he simply replied, “They can’t hurt.”)

I have spent most of my life as a printer in such environs so the first few images bring a flood of memories from the last twenty-five years: Printing in Helen Buttfield’s ancient darkroom above the old Irving Klaw Studio where Betty Page was often photographed at 212 East 14th street; Trying to print on GAF photo-paper that had expired in 1968 – the same year I was born; My printing teacher Sid Kaplan pouring his hot coffee into the developer tray because the chemistry was “too cold”; Coming home to find a pigeon sitting on my film drying lines in my improvised darkroom in my 35th street tenement apartment. Discovering my cat Bun-Bun had once again used one of my 16X20 developing trays as a litter box. Having my exhaust fan tumble out of my window and somehow shatter my downstairs neighbor’s window. The shrill beep of my Gra-lab enlarger timer as it counted down: 5, 4, 3, 2…

Adam Bartos’s Darkroom is available from Steidl this now.

Jeffrey Ladd is a photographer, writer, editor and founder of Errata Editions.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com