In 2005, I set out to photograph my home state of South Dakota, a sparsely populated frontier state on the Great Plains with more buffalo, pronghorn, coyotes, mule deer, ring-necked pheasants and prairie dogs than people. It’s a landscape dominated by space and silence and solitude, by brutal wind and extreme weather. I was trying to capture a more intimate and personal view of the West. I was trying to capture what all that space feels like to someone who grew up there. A year into the project, however, everything changed. One of my brothers died unexpectedly. For months, one of the few things that eased my unsettled heart was the landscape of South Dakota. It seemed all I could do was drive through the badlands and prairies and photograph. I began to wonder: Does loss have its own geography?

That first year of grieving was a blur of motel rooms, back roads, and dreams of my brother. I still remember, however, one particularly elusive, haunted, dreamlike image. One overcast day on a deserted country road in the Missouri River valley, I was startled by a flock of some thousand blackbirds. I was mesmerized by how the birds flew through the stormy, unsettled Western sky as if they were one huge, dark, undulating, ravenous creature, picking clean the remains of the corn and sunflower fields in the last days of autumn.

For days when I’d least expect it, I’d see the blackbirds descend upon a field. It didn’t seem to matter how quickly I stopped the car and raised the camera to my eye. Inevitably, the dark flock vanished as quickly as it had appeared.

For at least a week, I kept dreaming about those blackbirds. Finally, one afternoon near the small town of Gray Goose, South Dakota, I saw the flock hovering over a field of sunflowers. This time I was somewhat more prepared—I had my camera around my neck, and, thanks to the dirt road’s wide shoulder, I could quickly pull over and rush toward the field, crouching low to keep from scaring off the skittery birds. I remember wondering what I’d say to the farmer if he caught me trespassing on his land.

Then something happened that I wasn’t expecting—the flock lingered in the field. Were there more seeds than usual to feed on? Were the towering sunflowers hiding me from the skittish birds? Slowly I inched closer until I was standing directly behind one of the tallest sunflowers in the field. Beneath its large bowed head, I clicked the shutter again and again until the dark flock vanished once more into the cold, grey, blustery November sky.

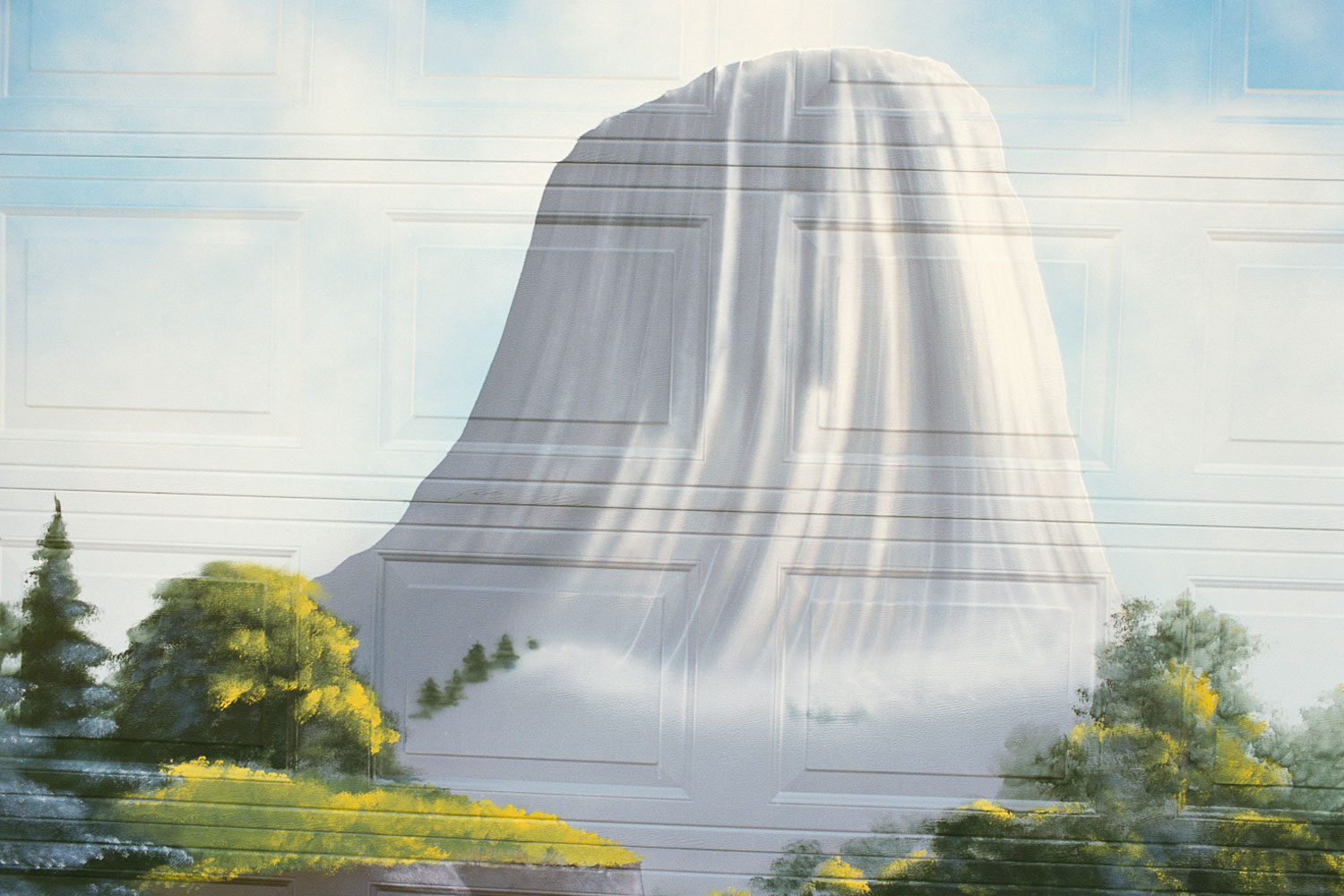

They say your first death is like your first love—and you’re never quite the same afterwards. After my brother died, my photographs started to change. They were more muted, often autumnal. I remember saying to the writer, Linda Hasselstrom at her ranch house near Hermosa, South Dakota, where I did much of the writing for the book, “I see summer, fall, and winter, in the photographs, but not spring.”

“When you’re grieving, there isn’t any spring,” Hasselstrom replied.

Looking again at the work now that My Dakota is finally a book, I realize that I was photographing this particularly dark time in my life in order to try to absorb it, to distill it, and, ultimately, to let it go. Not only did my first grief change me, but making My Dakota changed me as well, both as a human being and as a bookmaker.

Rebecca Norris Webb is a New York-based photographer. More of her work can be seen here. My Dakota (Radius Books) will be launched at the International Center of Photography in New York City on May 24. There will be an exhibition of the work at the Dahl Arts Center in Rapid City, South Dakota, from June 1 through October 13.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com