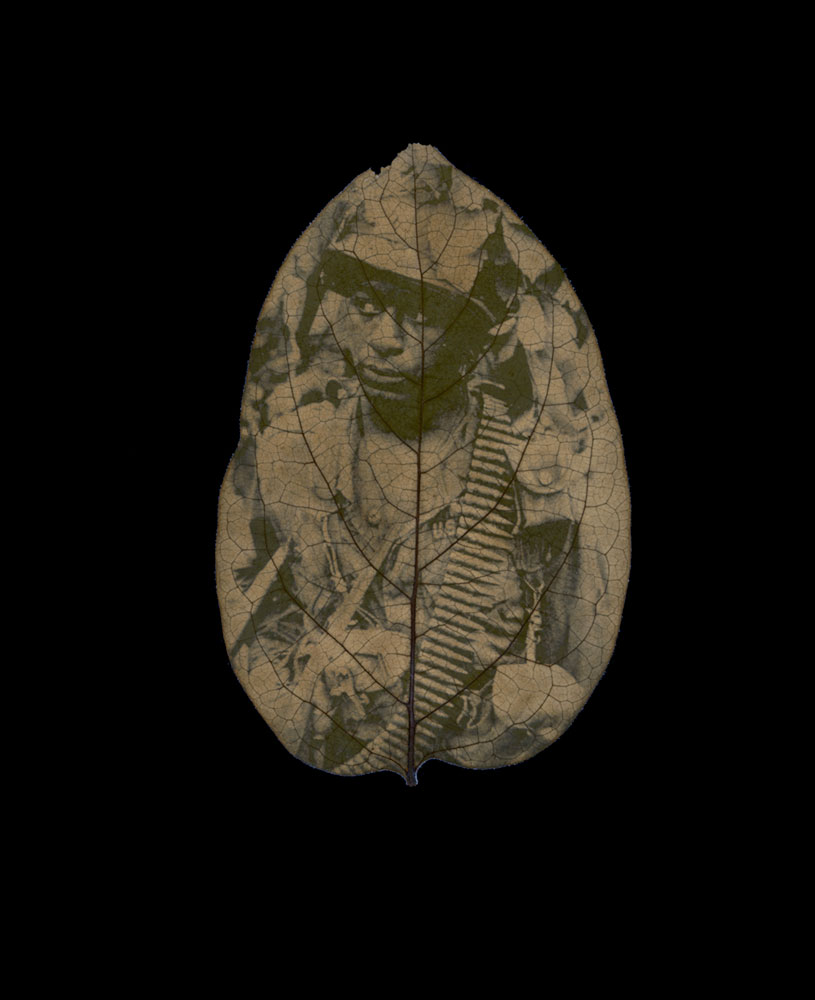

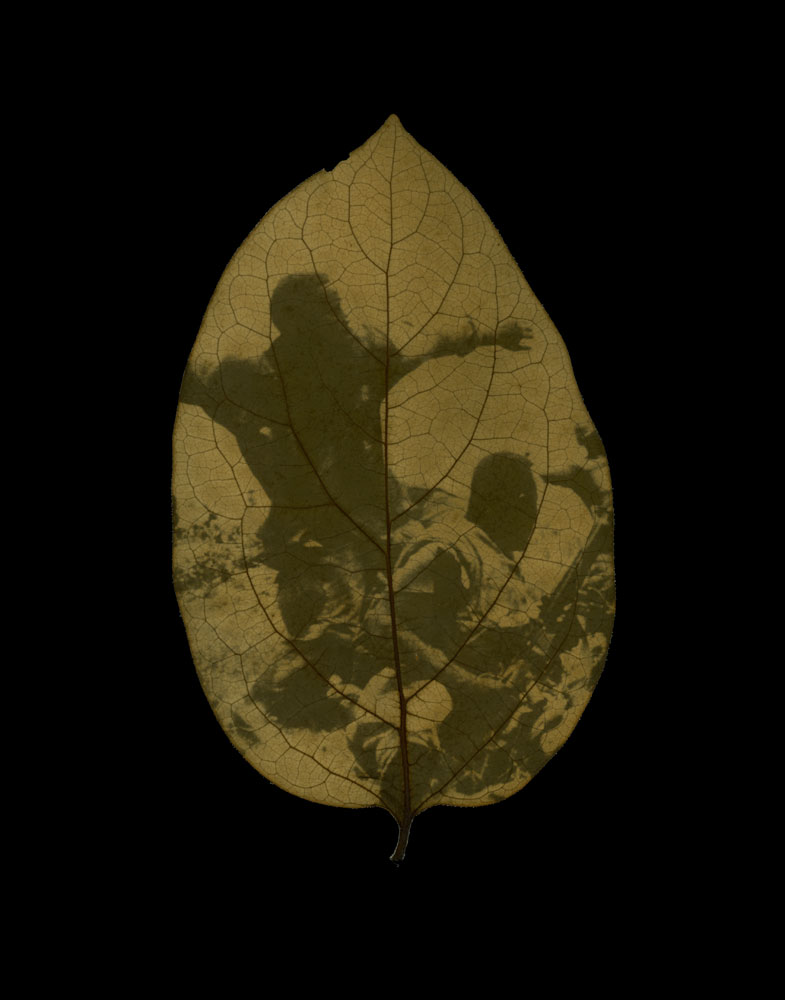

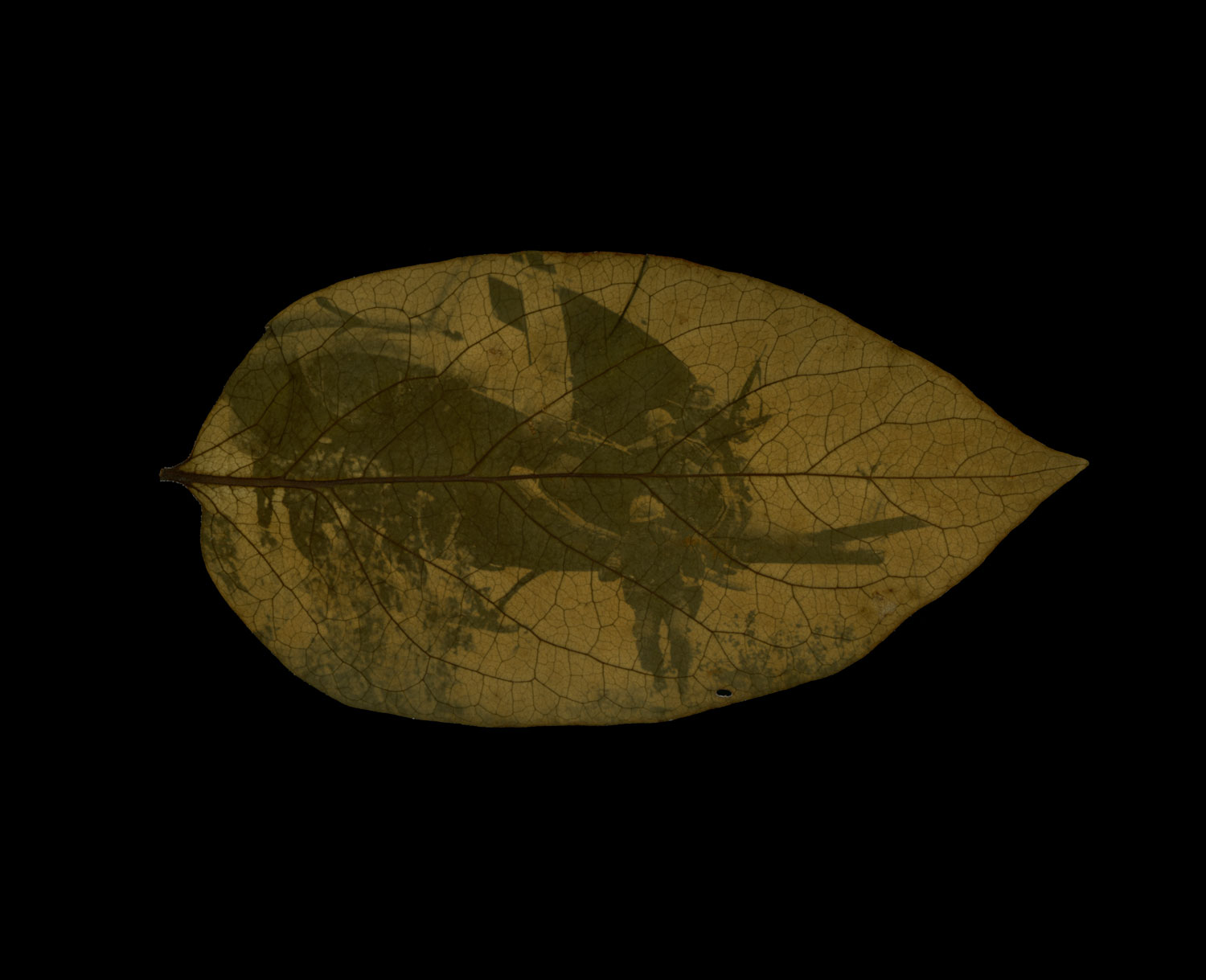

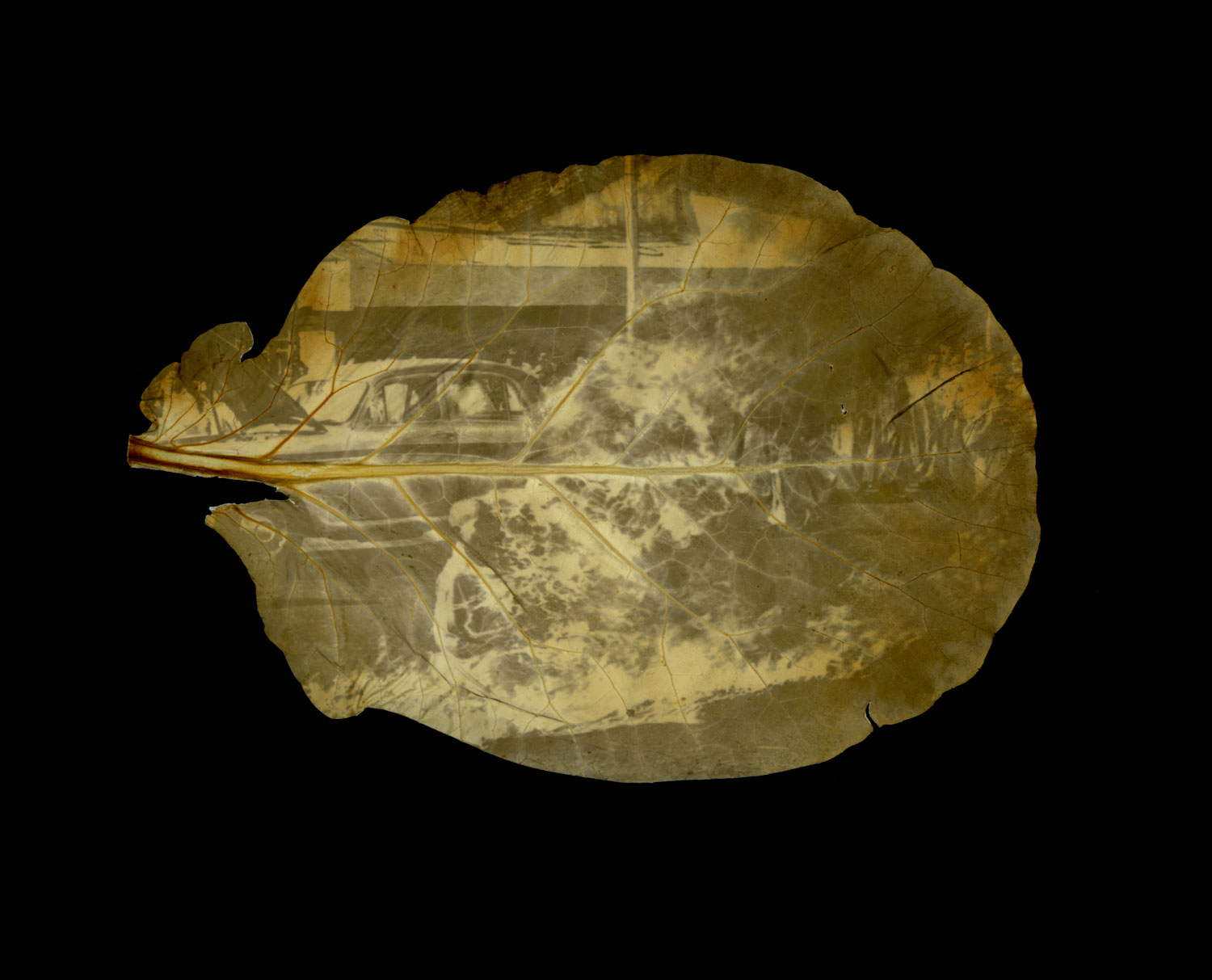

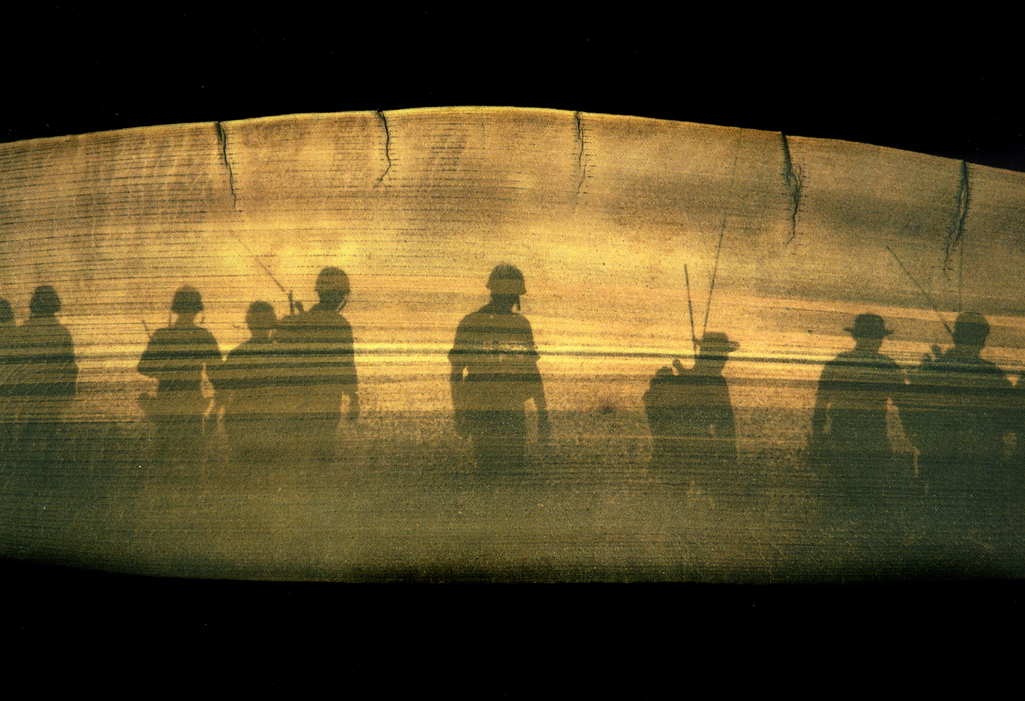

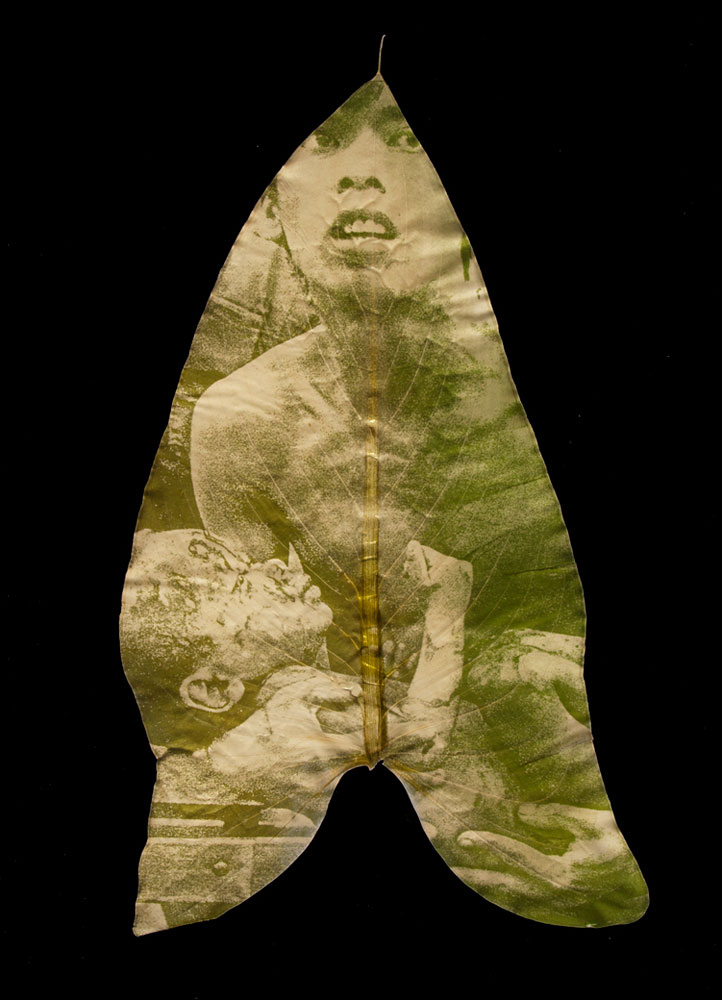

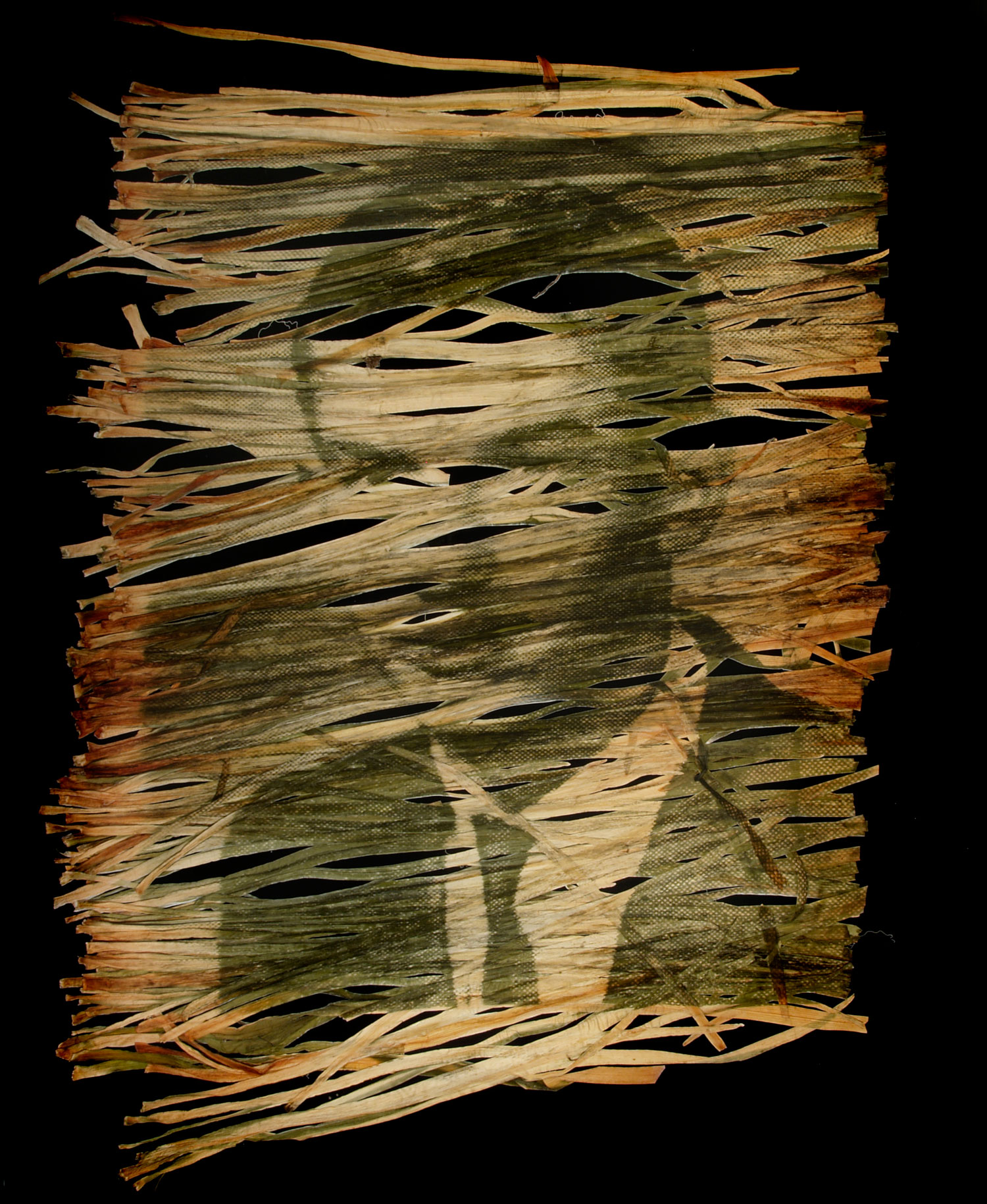

When Binh Danh was a child he noticed the impression of objects left on a grass lawn over time. This observation, combined with an early fascination with science and a personal legacy of war—Danh immigrated to the States as a child refugee from Vietnam—would later coalesce into the series of images for which he is most widely known. Danh appropriates iconic images of the Vietnam War and prints them on organic material such as leaves and grass, using a unique printing process he calls Chlorophyll printing. The images—ethereal and fragile, endowed with a sense of heart-wrenching loss—speak poetically of memory, impermanence and the remnants and aftermath of war.

April 30th marks the 37th anniversary of the fall of Saigon, the official end of the Vietnam War. For Danh, a Vietnamese American, the legacy of that conflict is complex and profoundly personal: photography is his means to connect with the painful shadows of that legacy by empowering a narrative that grounds him in his own identity. “It’s something that my parents I think want to talk about, but it’s difficult for them to communicate because they have such a direct relationship to what happened,” he says.

The artist uses two different processes to create his images. The first resembles traditional black and white printing where a negative is placed on a living patch of grass or leaf. Like the imprint of a hose on a green lawn, light-blocking material removes the green chlorophyll pigment from organic matter. The image transfers when the dark portions of the negative block light, removing the pigment, while the transparent sections keep the underlying portion of the grass or leaf alive. In the second method, fake grass is cut and layered on a board to form a canvas onto which the artist projects a positive. The clear part of the transparency that lets sunlight through gets washed out, forming an image.

In an ode to the impermanence and fragility of memory, it is impossible to chemically fix the photograph like a silver gelatin print. The artist recommends pressing the material in a book to retain color, and displaying and storing them away from direct sunlight. However, Danh takes this a step further and casts his work in resin, which, for him, becomes a way to preserve the leaf to hold onto that memory. “I feel that when we forget about the memory of war, war can happen again,” he says. “And of course in this country we forget very quickly.”

Binh Danh is an artist presented by Haines Gallery in San Francisco and Lisa Sette Gallery in Scottsdale, Ariz. See more of his work here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in Februar

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com