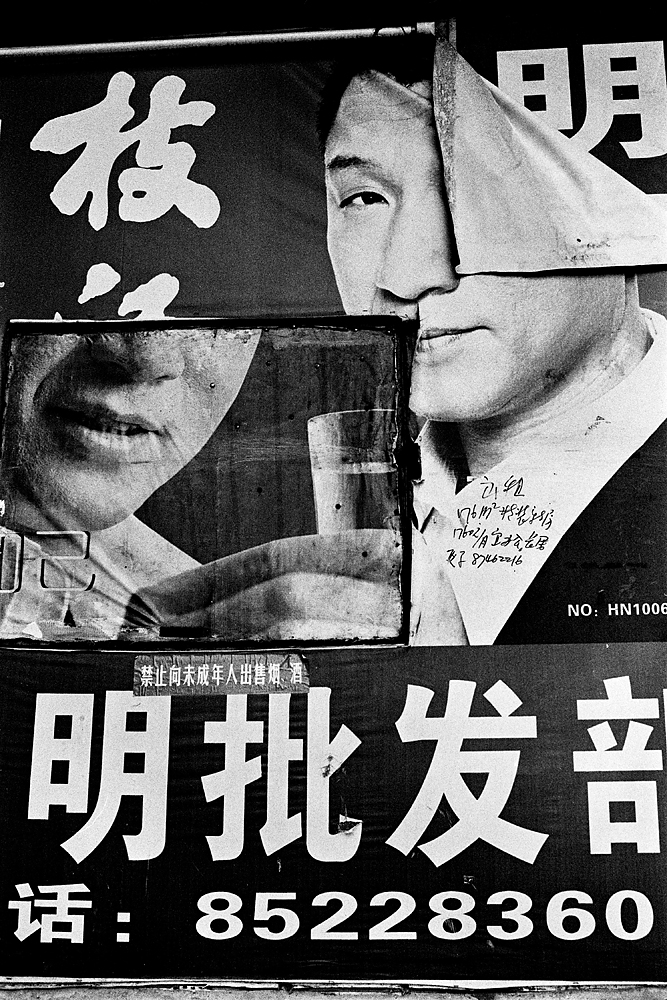

Rather than see the city of Changsha fall into Japanese hands during World War II, Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek decided to burn the entire city to the ground in 1938. Out of the destruction, Changsha, now a metropolis of six million, has risen from the ashes.

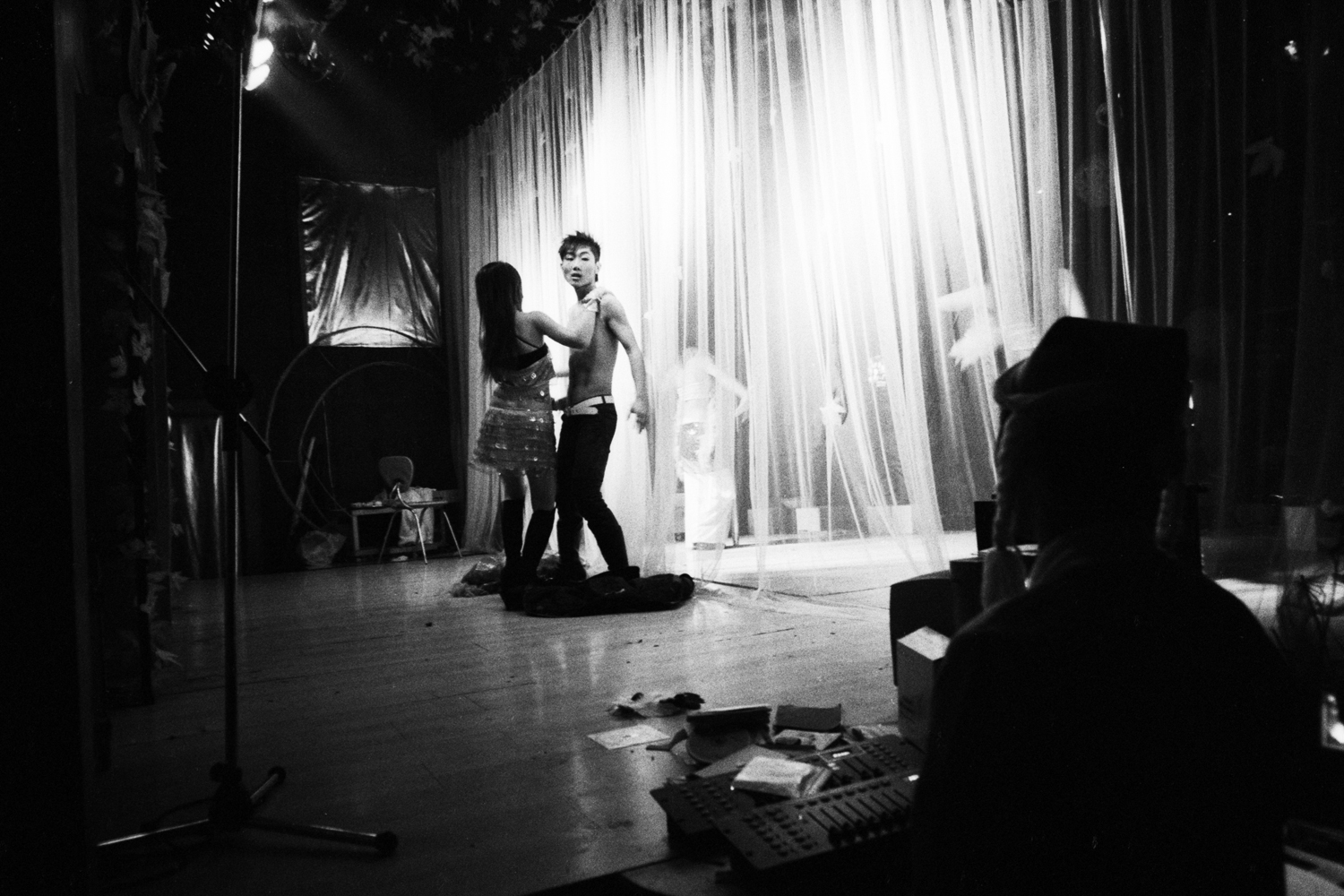

Photographer Rian Dundon spent the last six years creating a gritty black-and-white exploration of people living and making their way in Changsha, as well as Hunan, in a geometrically evolving civilization. A dizzying place, where “bit-players in the unfolding epic of China’s development” deal with forces beyond their control, he says.

Dundon describes Changsha as “Blade Runner meets Brooklyn: a sprawling warren of ad-hoc concrete, grand boulevards and neon dreams laced with an energy that made me dizzy.” After six years living and working in China, the photographer has begun composing a book dummy and is selling advance copies via emphas.is to help fund its publication.

The photographer originally moved to China thinking it was only a yearlong commitment, tagging along with his then-girlfriend who had landed a position teaching English for Princeton University. Living in China subverted Dundon’s imagination, and he found himself surprised by the disparity between what he had envisioned and what he actually found. “I had expected something more exotic, more foreign,” he says. “My notions of China were of a place removed from the rest of the world.”

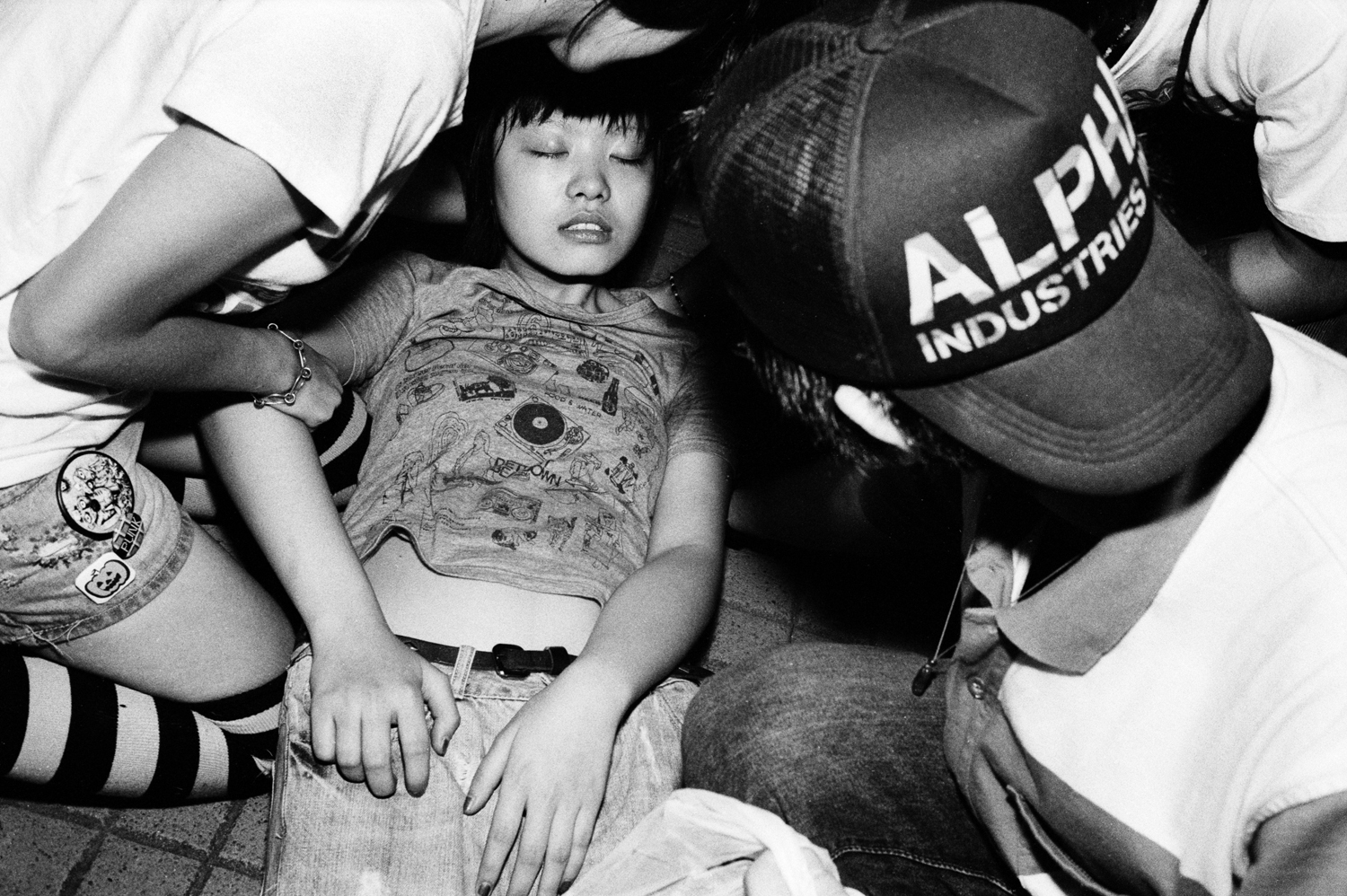

Dundon began to learn Mandarin in the city’s pool halls, counting balls in Chinese, and practicing his language skills with local billiards sharks and spectators. He befriended a liquor salesman and a bar owner who introduced him to a grittier side of the city’s nightlife. By day, he explored Changsha, soaking in the rhythm and the texture of the place. “I did my best to absorb everything, every bit of local language or news or culinary offering. And I photographed, always photographed. Only now I wasn’t just a visitor or a journalist,” he says. “Without a story to cover or a deadline to meet, I consigned myself to the sensuality of living, engaging with the people I met and staying open to different modes of experience,” Dundon wrote in his project outline.

“After one year I knew I had only scratched the surface. There were so many layers to dig through. And there’s no way to rush this kind of thing,” Dundon says. Despite the fact that his girlfriend left after a year, Dundon ended up staying in China for six.

Rather than take a traditional journalistic approach, Dundon photographed in a more experiential way. In his work, Dundon found himself “trying to maintain a continuous sense of personal narrative in my work—a unifying perspective. In China I was more interested in atmosphere and attitude than a strictly defined subject or story,” Dundon says. “And I had to accept the fact that I knew nothing. That only by staying open to different tracks of experience would I be able to produce something honest. I needed to give up control. Allow myself to be led.”

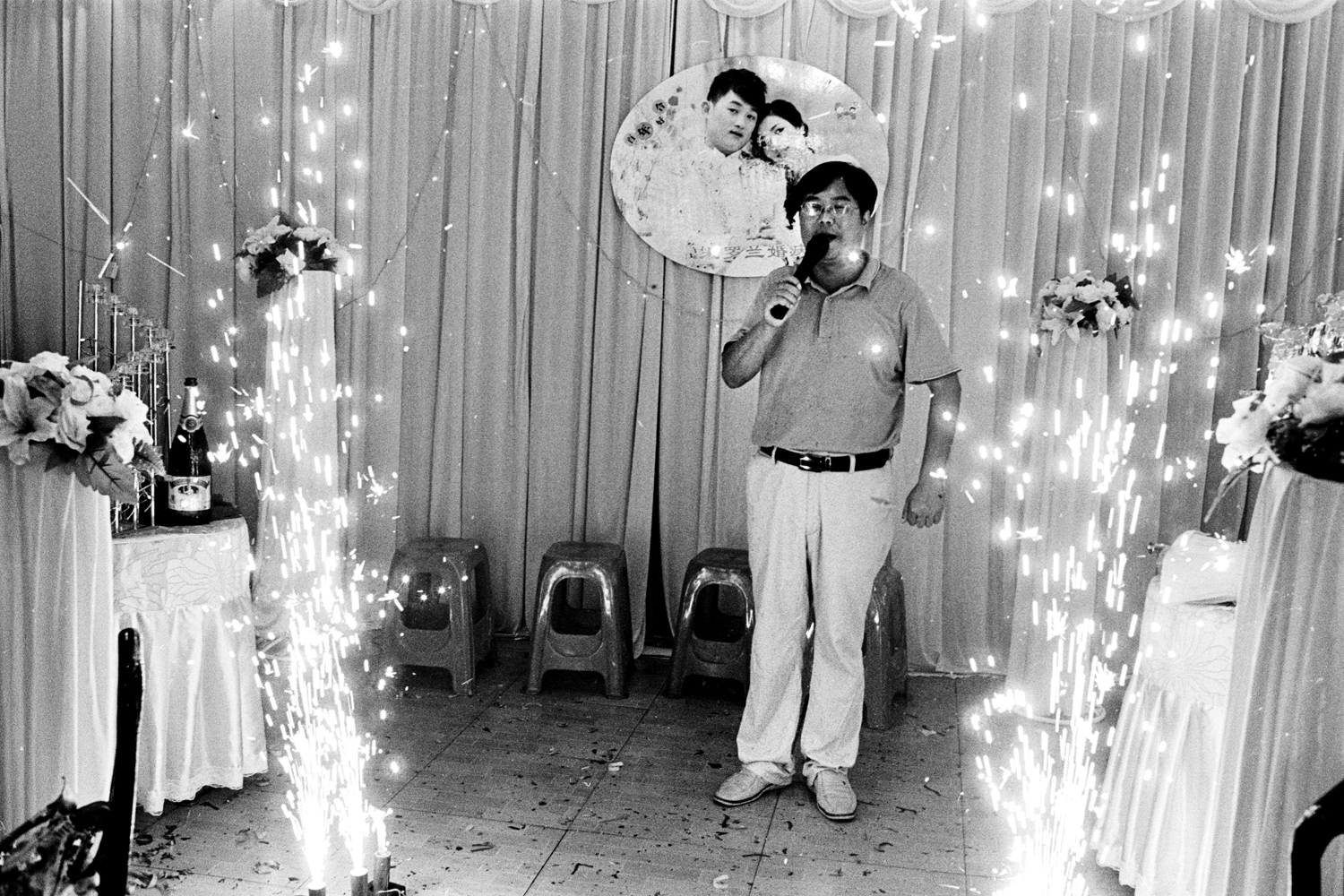

In Changsha, Dundon befriended a crew of funeral planners, cemetery consultants and speculators. “The death business is booming in China. Most of them were young kids fresh out of college who kept a canny sense of humor despite the somber surroundings,” he says. Despite the growth opportunities in the industry, these ambitious youths were stuck in an odd interstitial area, between the cultures of both ancient and modern China. The power and presence of sprits and ghosts is still respected by many Chinese, and for this group, that meant keeping their work secret—save for a small cadre of family members and friends. “Most people don’t want to get close to someone who spends their days with the dead. And that shared experience of exclusion was the glue that bound their tightly knit group together.”

Dundon took a trip home to rural Liling County with one of his Changsha confederates. “He told me that nobody in his village could know what he really did for a living.” Dundon says. Despite his success in the city, “he was still forced to lie about his job when he went home for holidays. After tasting city life he said he could never move home again.”

Rian Dundon is an American photographer. See more of his work here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com