Leonard Freed had seen his fair share of violence. The Brooklyn-born photographer, who died in 2006, spent nearly a decade behind the lens encountering the American Civil Rights movement in the 1960’s as well as events in Israel surrounding the 1967 Six-Day War. So when New York City faced near-bankruptcy and soaring crime rates in the 1970’s, he was prepared to engage the whole rawness of his hometown. But for Freed, rawness did not only mean violence. Instead, the gritty reality also inspired one of the deepest and most complex everyday studies of the storied New York Police Department (NYPD).

Forty years have passed since Freed first began to document these officers. And although his original book, Police Work, published in 1980 and no longer in print, a larger collection of prints from the series is on display at the Museum of the City of New York through mid-March.

Freed began photographing the NYPD as a commission for the London Sunday Times in 1972. When published—accompanied by an article titled “Thugs, Mugs, Drugs; City in Terror”—the collection raised more than an uproar. Mayor Jon Lindsay called the article “a gross insult to the city,” and the Daily News even sued. Freed himself had a different angle on his own photographs. “They wanted blood and gore,” he told Worldview magazine about the article. “But I was more interested in who the police were…I wanted to get involved in their lives.”

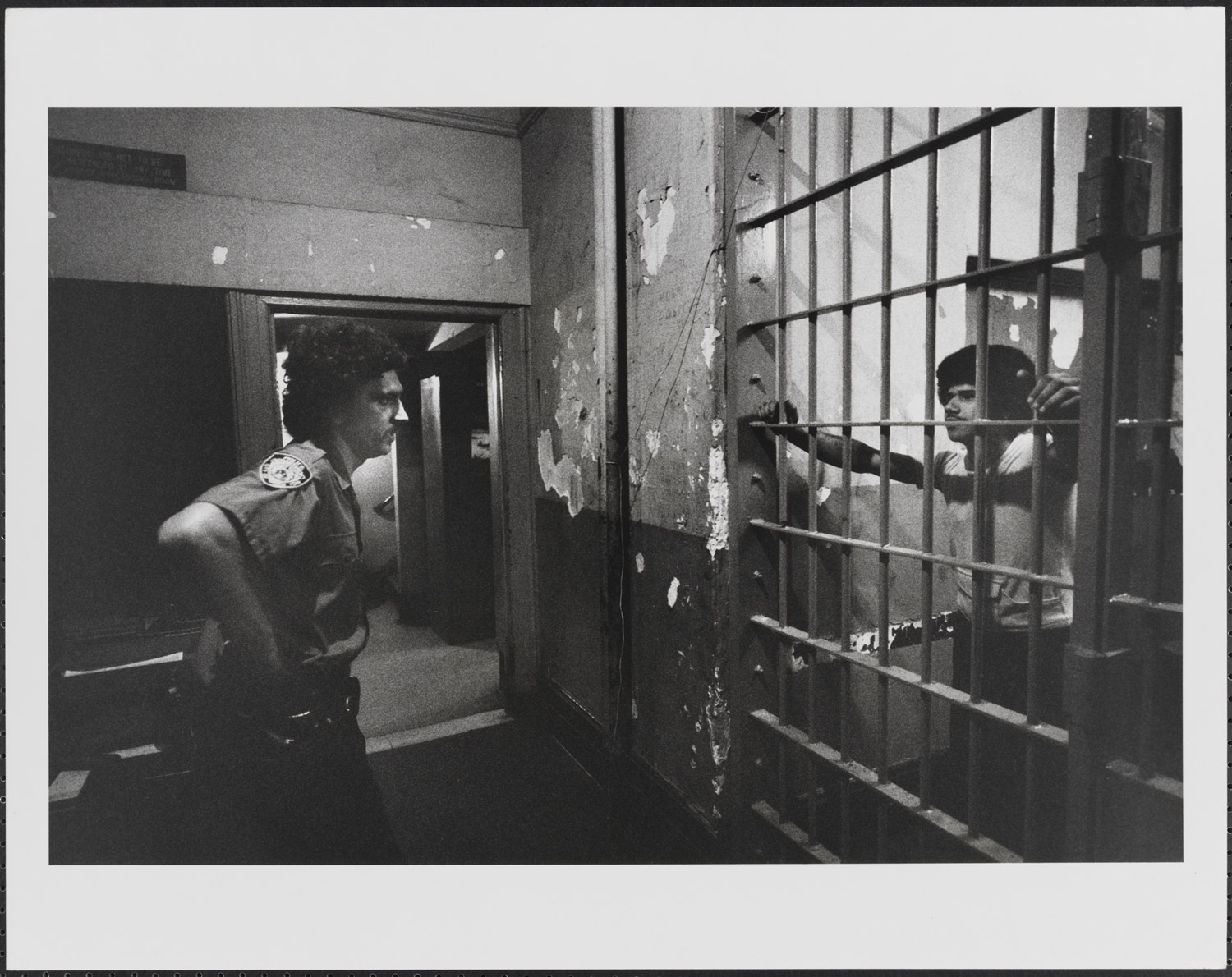

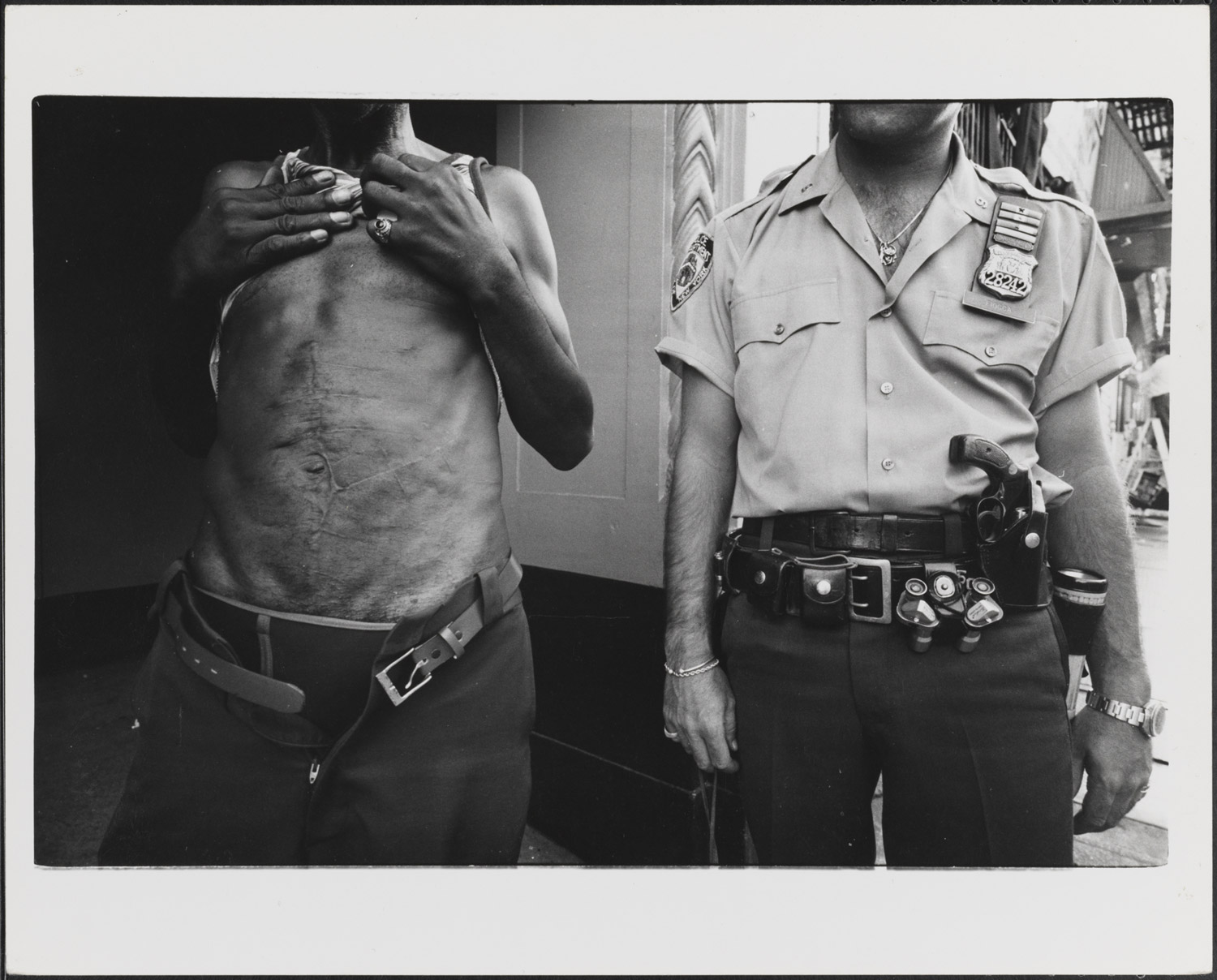

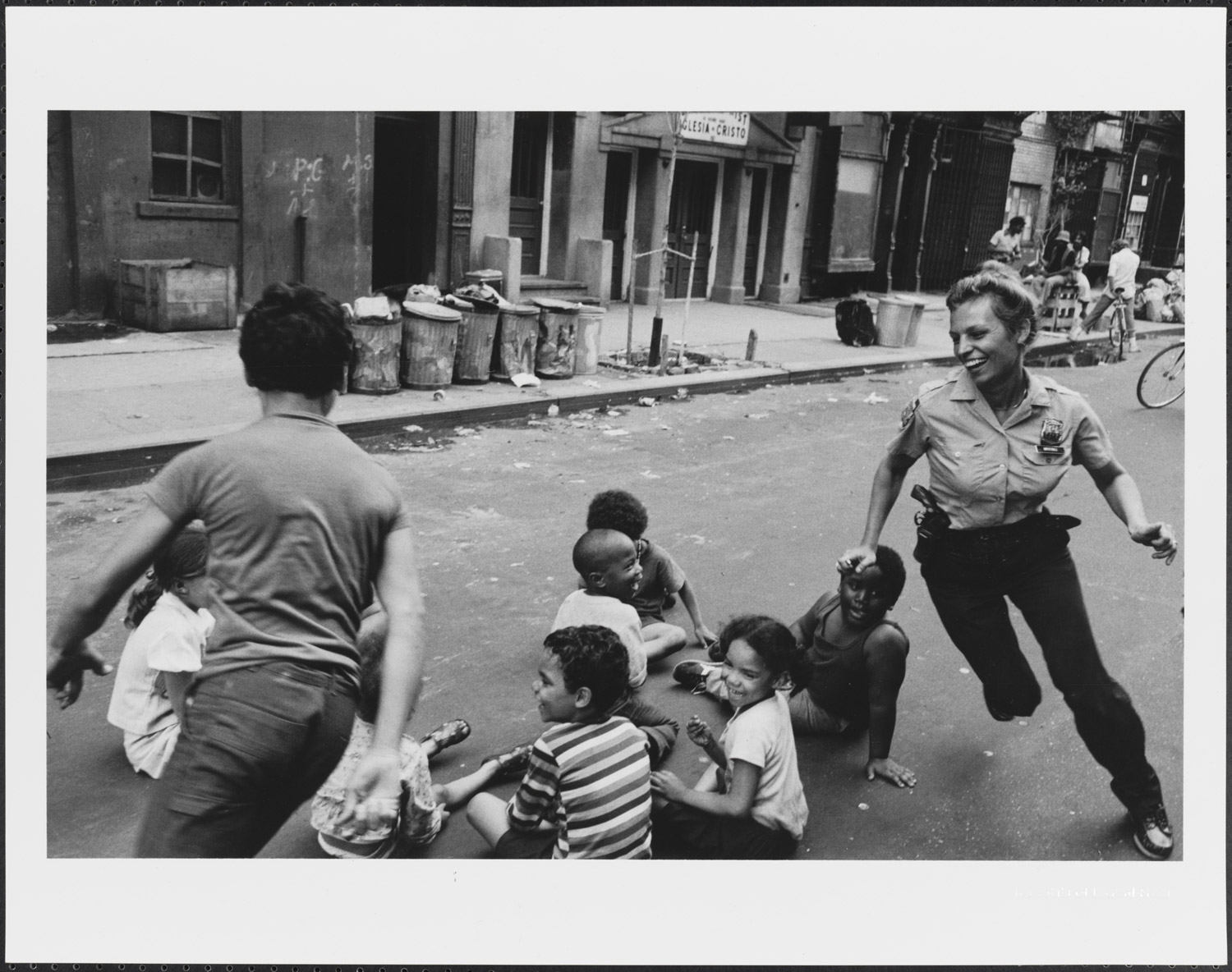

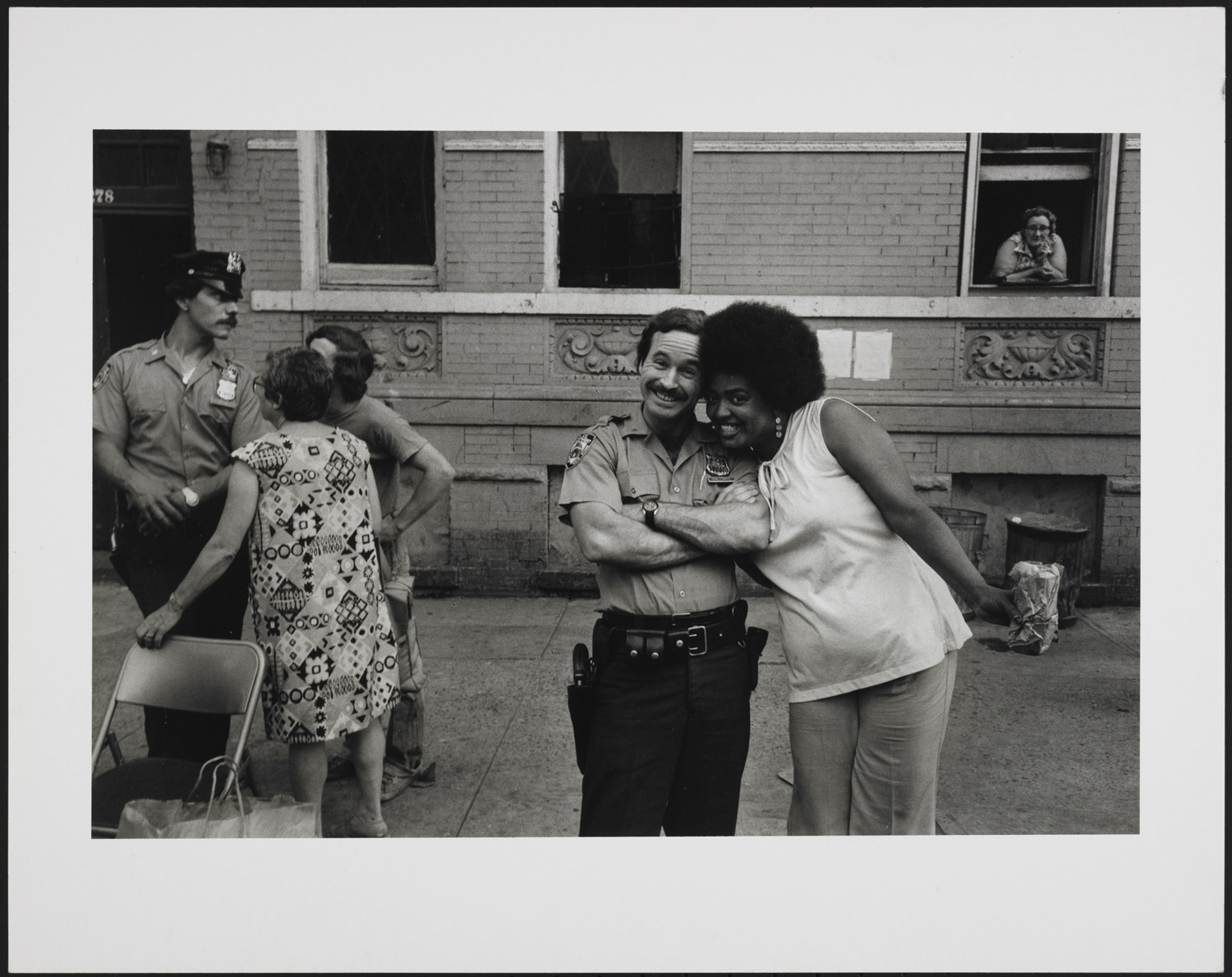

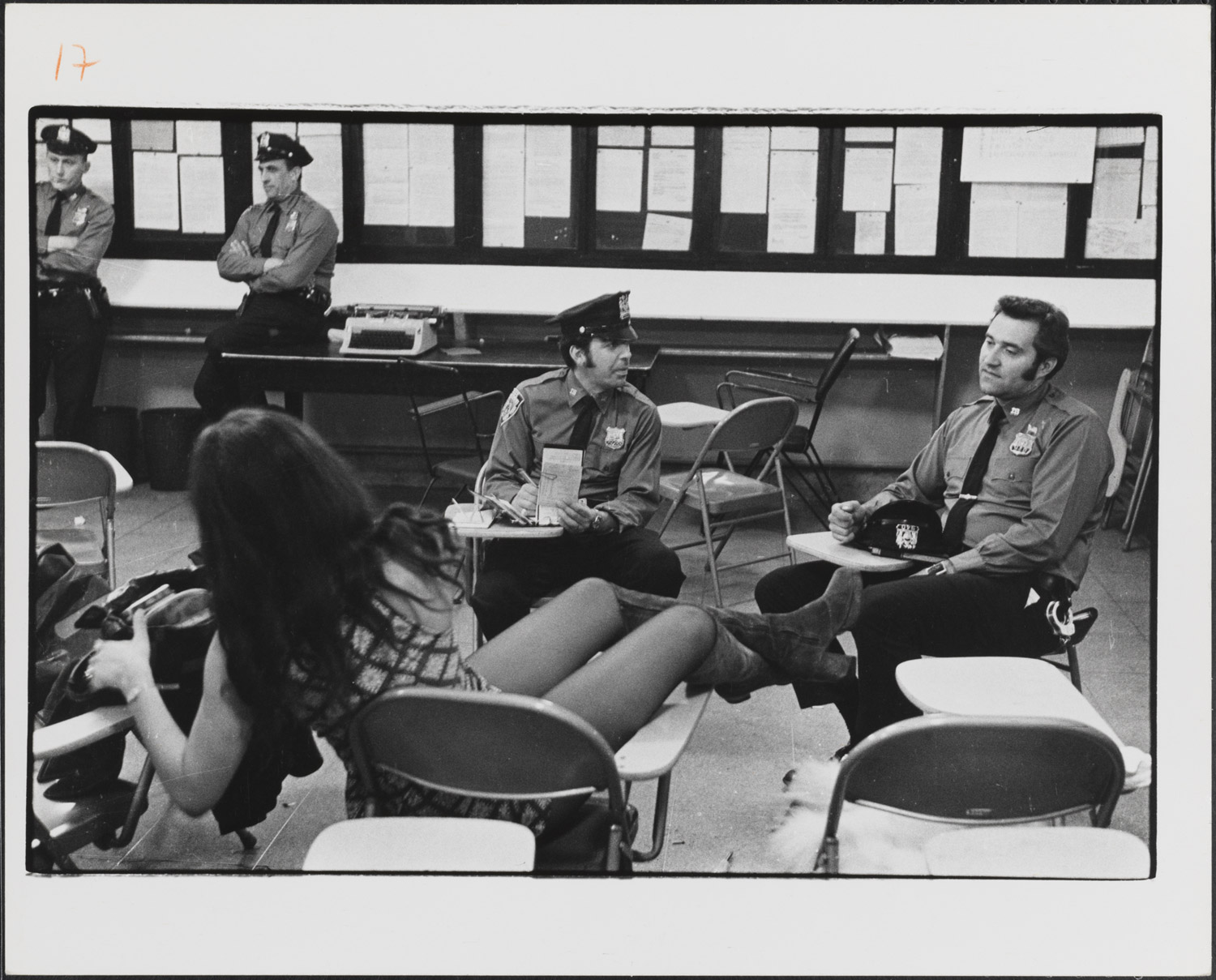

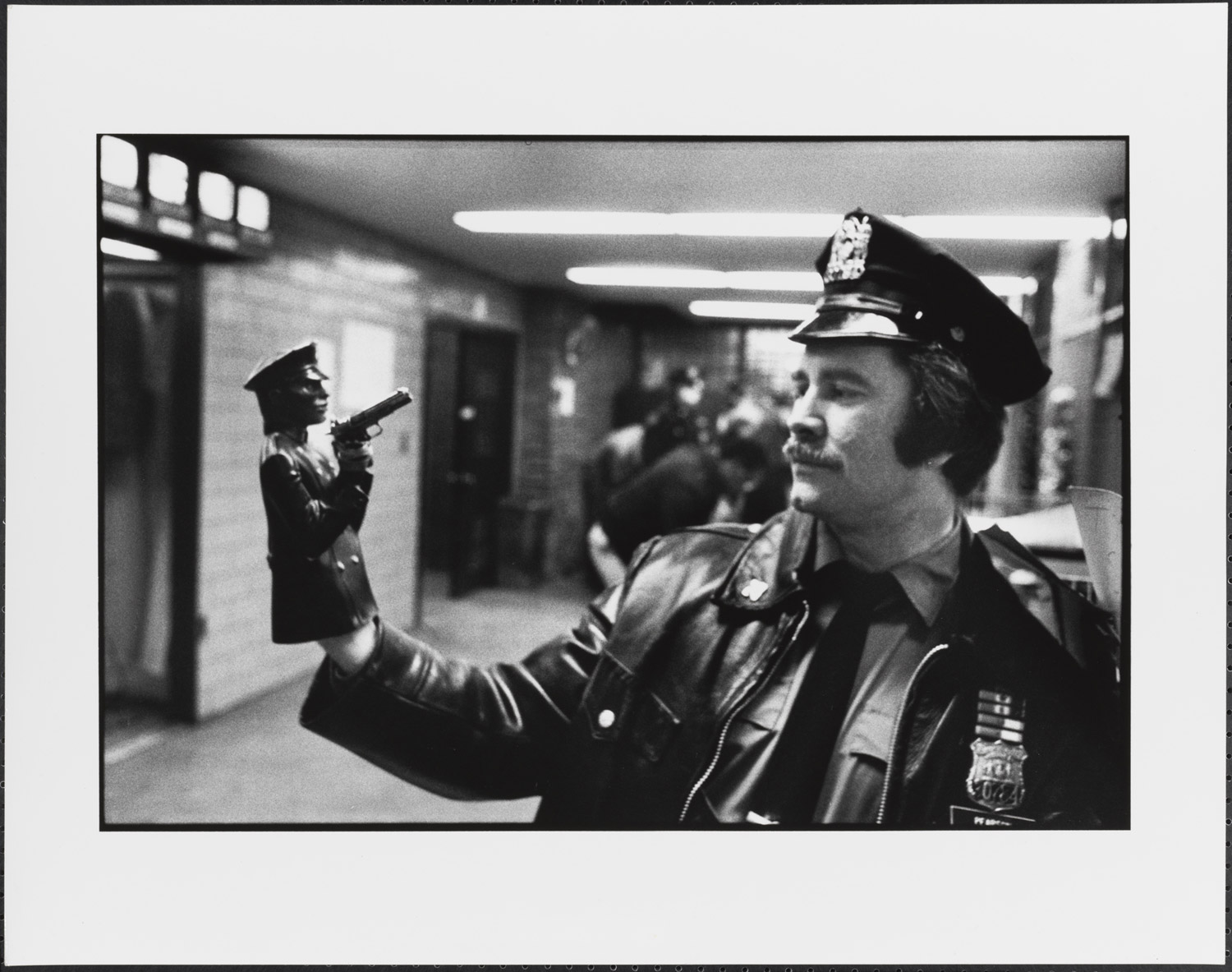

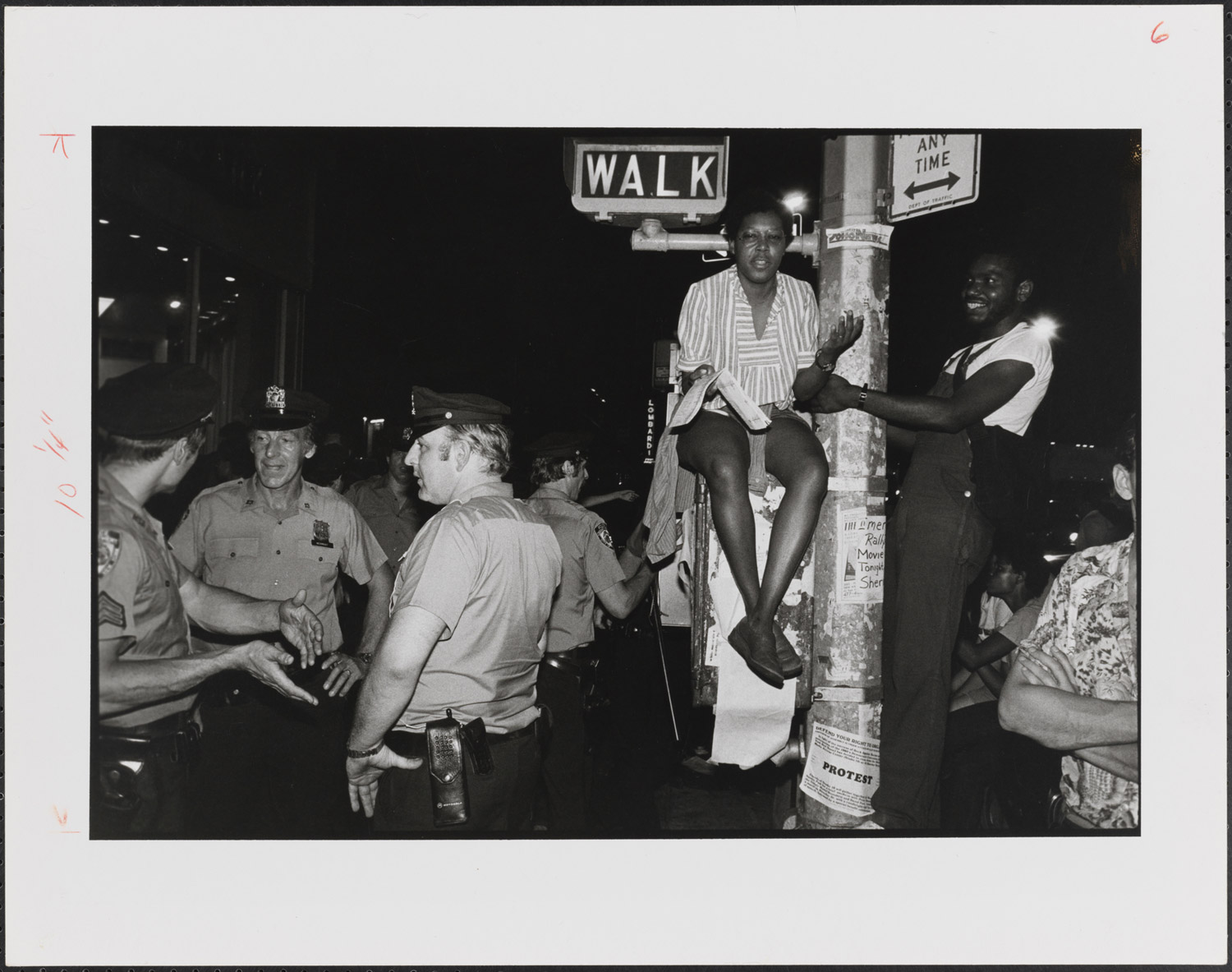

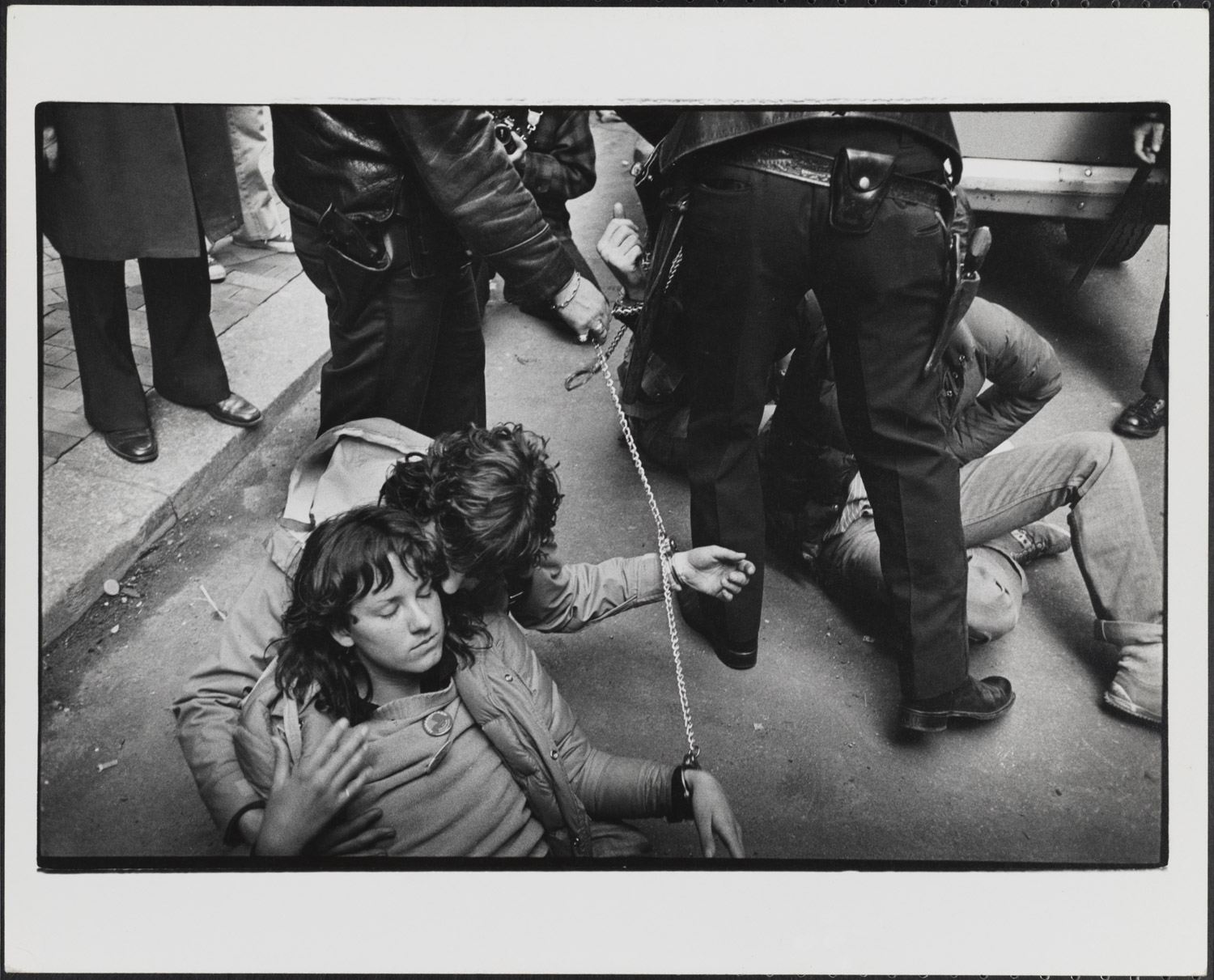

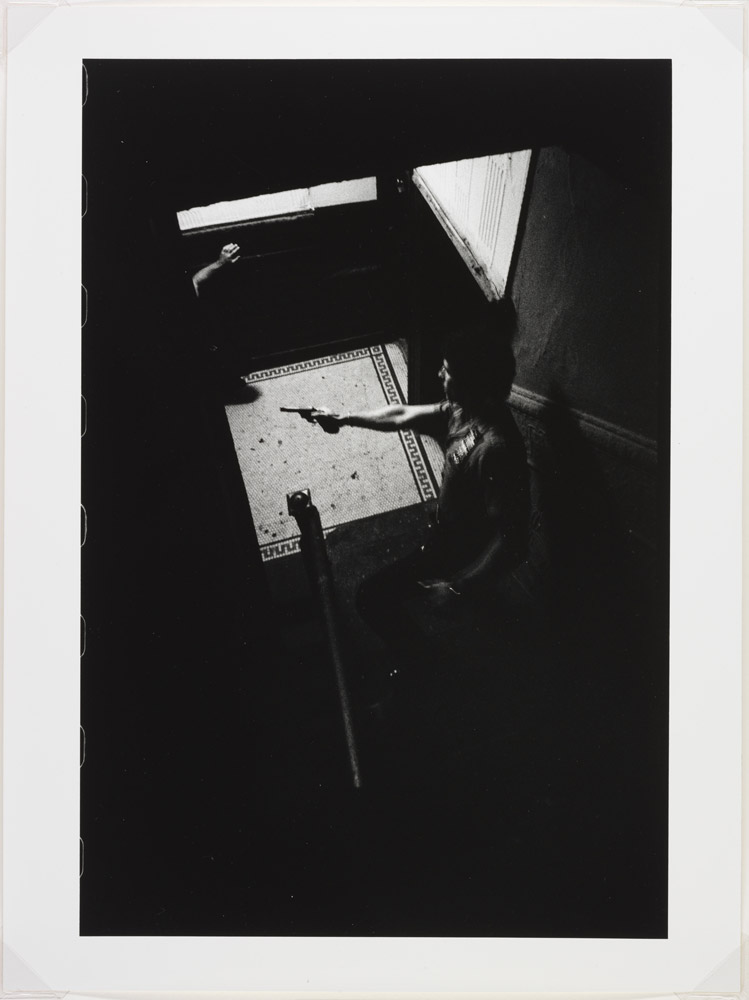

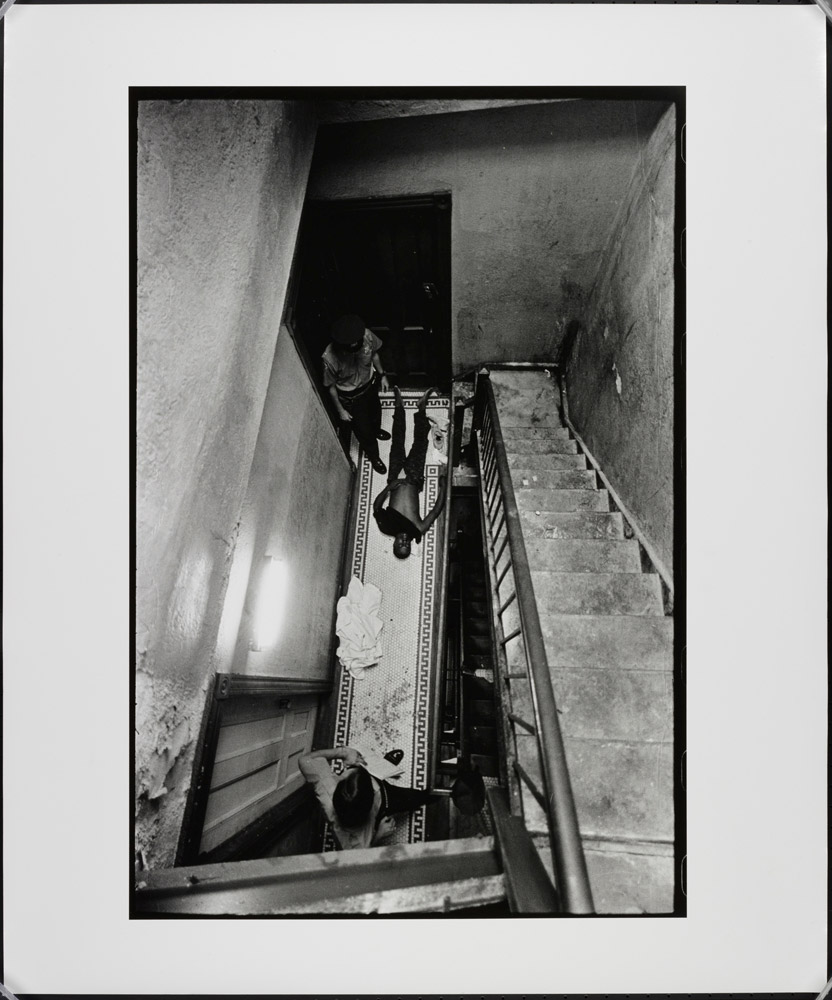

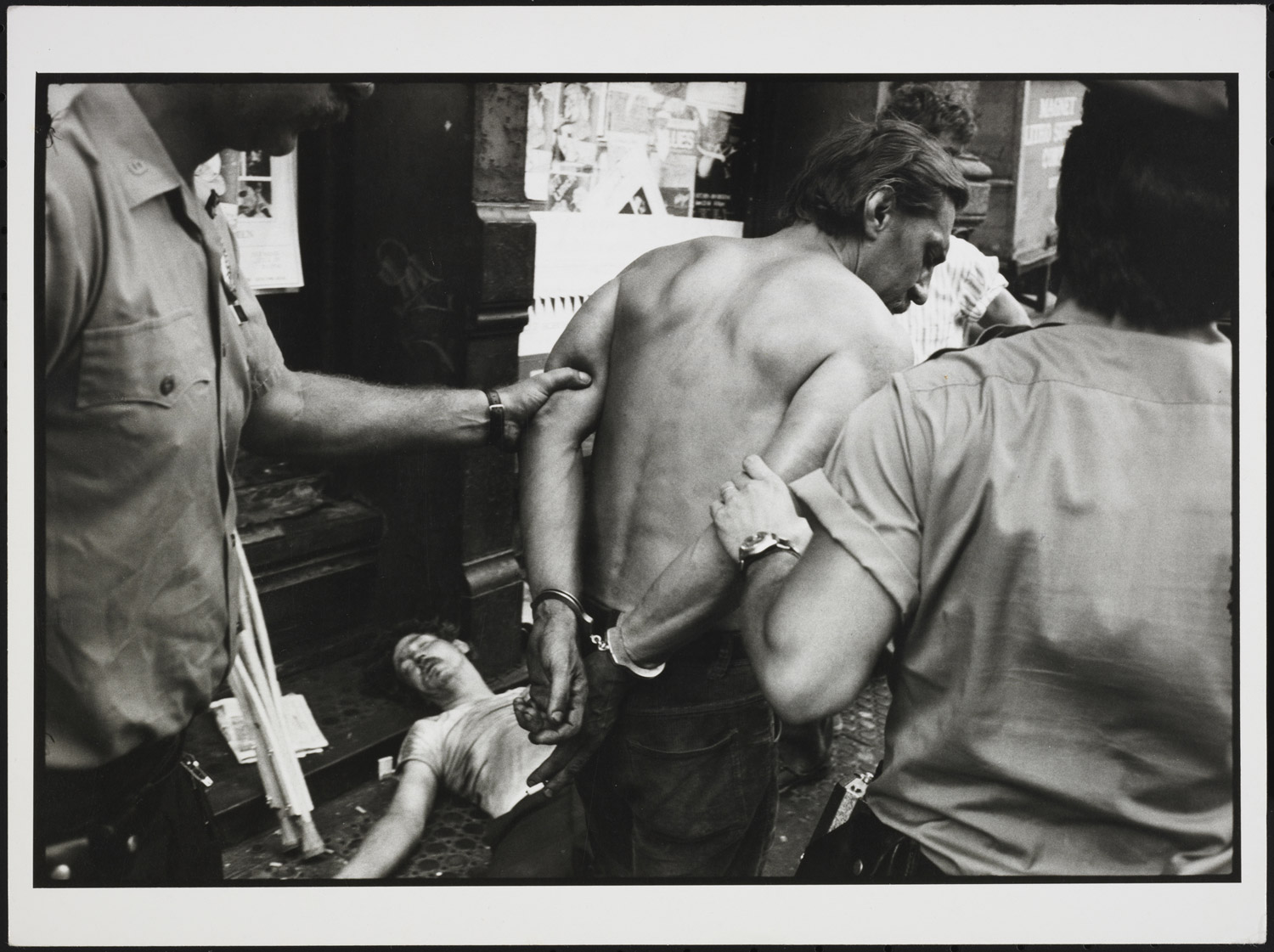

So Freed did, accompanying the officers during drug busts, protests and murders that furthered a common, negative perception of the storied NYPD. But the photographer also saw a complex picture. He was on scene as a policewoman played duck-duck-goose with neighborhood kids. Elsewhere, Freed’s lens captured an African-American woman who embraced a white officer and quipped, “Isn’t he cute?” And above all, he saw a force made up of people were more like the rest of the middle class than many Americans thought. “I chose this title (Police Work),” Freed once said, “because the police are workers, they are not in command, they are not the mayor, they are not the lawyers. They are ordinary working people.”

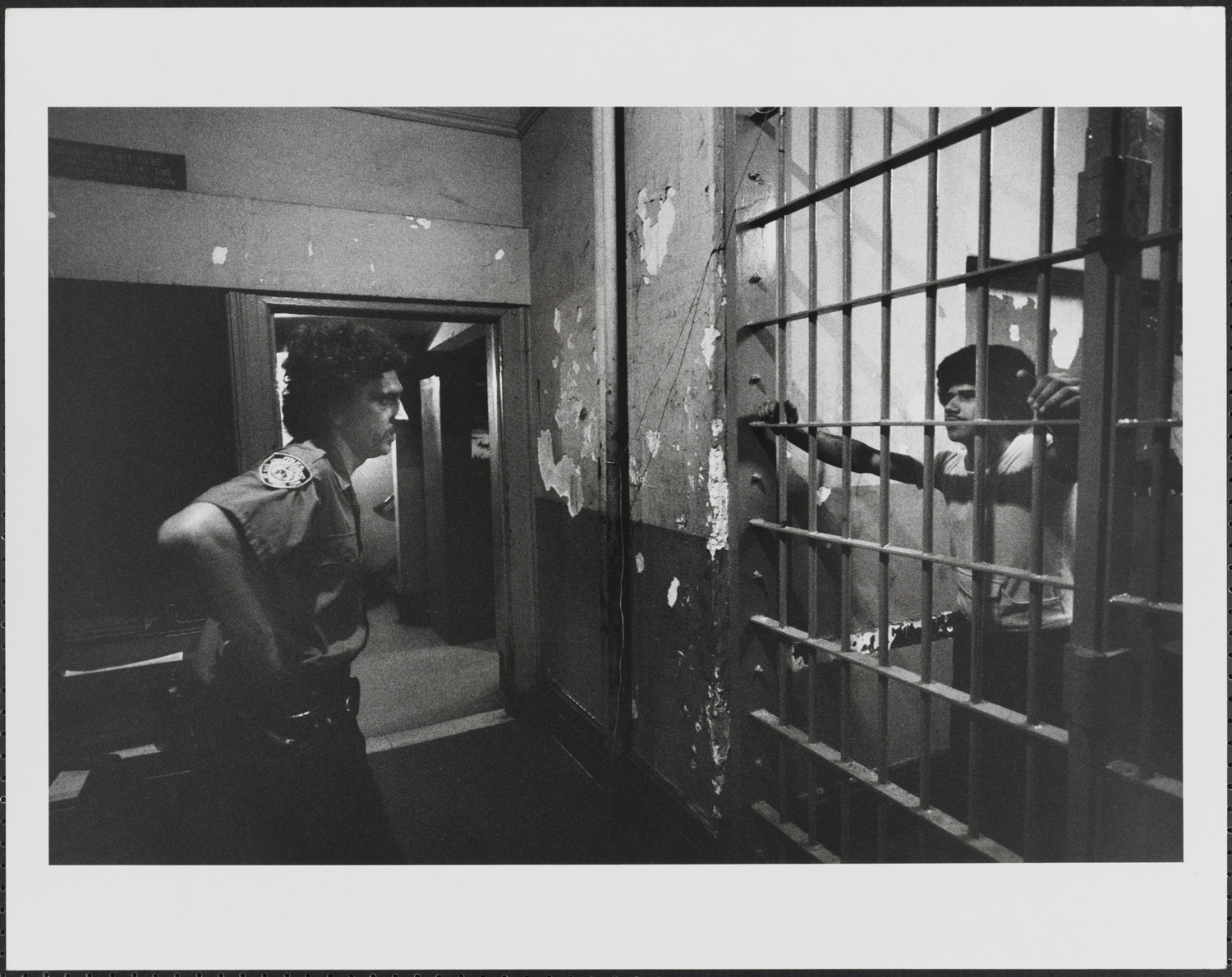

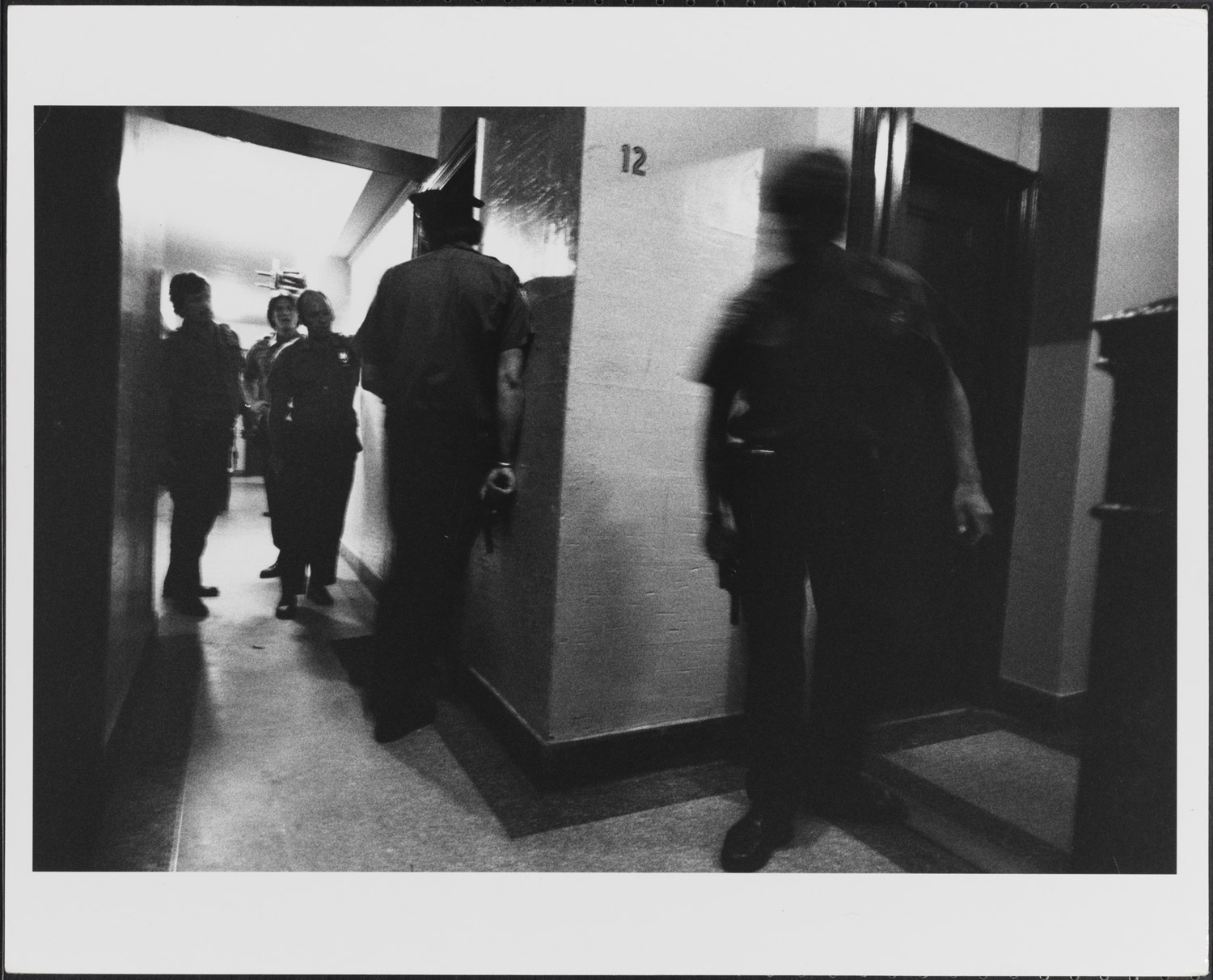

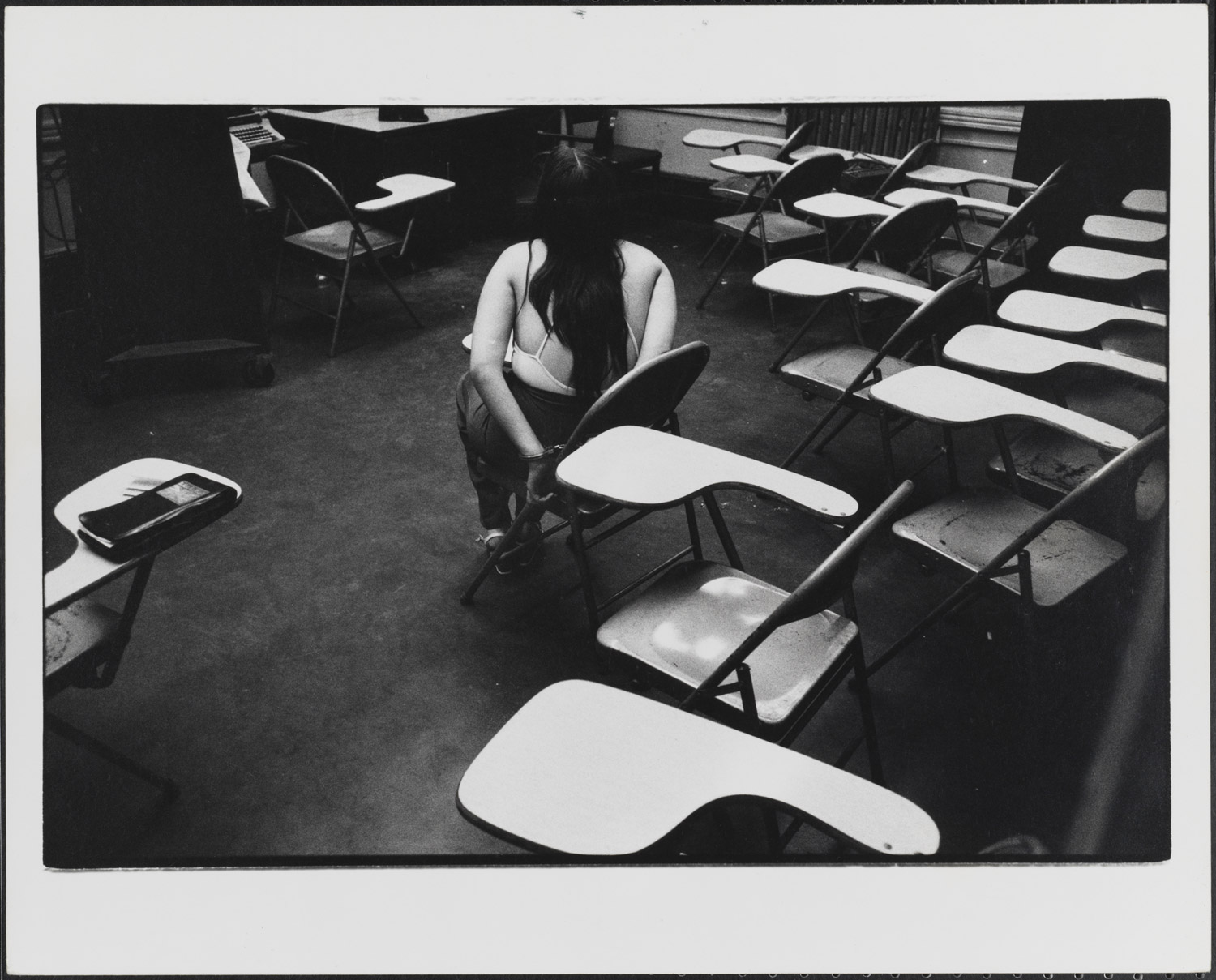

Freed worked on his Police Work collection for nearly a decade and eventually published more than 100 images. “As a series, it is one of his best,” says Sean Corcoran, curator of prints and photographs at the Museum of the City of New York. “The more you see, the more you see all the angles.” Many of Freed’s photos are framed in very close proximity. “You are right there in the middle of it all,” says Corcoran. “He is not standing back. He is not behind that police tapeline. He is in there with them, experiencing things with them.”

This newfound nearness opened many Americans to the police world for the first time. In his day, there was no Law and Order or CSI. “Today we think we know what it is to be a cop based on these shows,” says Corcoran. “But these guys are working with type writers, and they are wearing very loud plaid. In some sense, his pictures are more real than the T.V. shows because he doesn’t pull punches—there are a couple of really tough murder scenes in these pictures. It goes back to the reality of the policeman’s experience.”

Police Work is on display at the Museum of the City of New York through March 18.

Elizabeth Dias is a reporter in TIME’s Washington bureau. Find her on Twitter @elizabethjdias.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Introducing the 2025 Closers

Contact us at letters@time.com