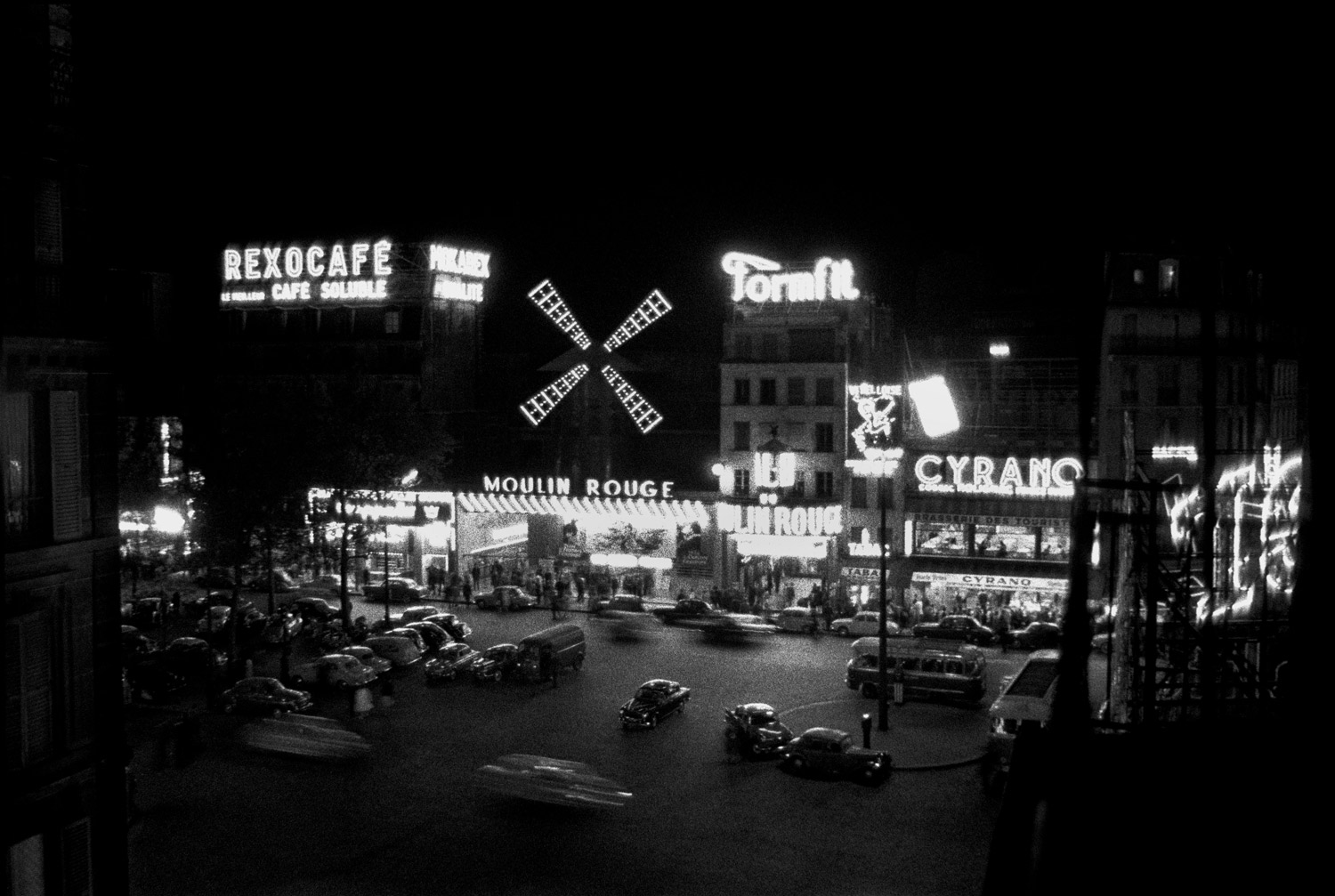

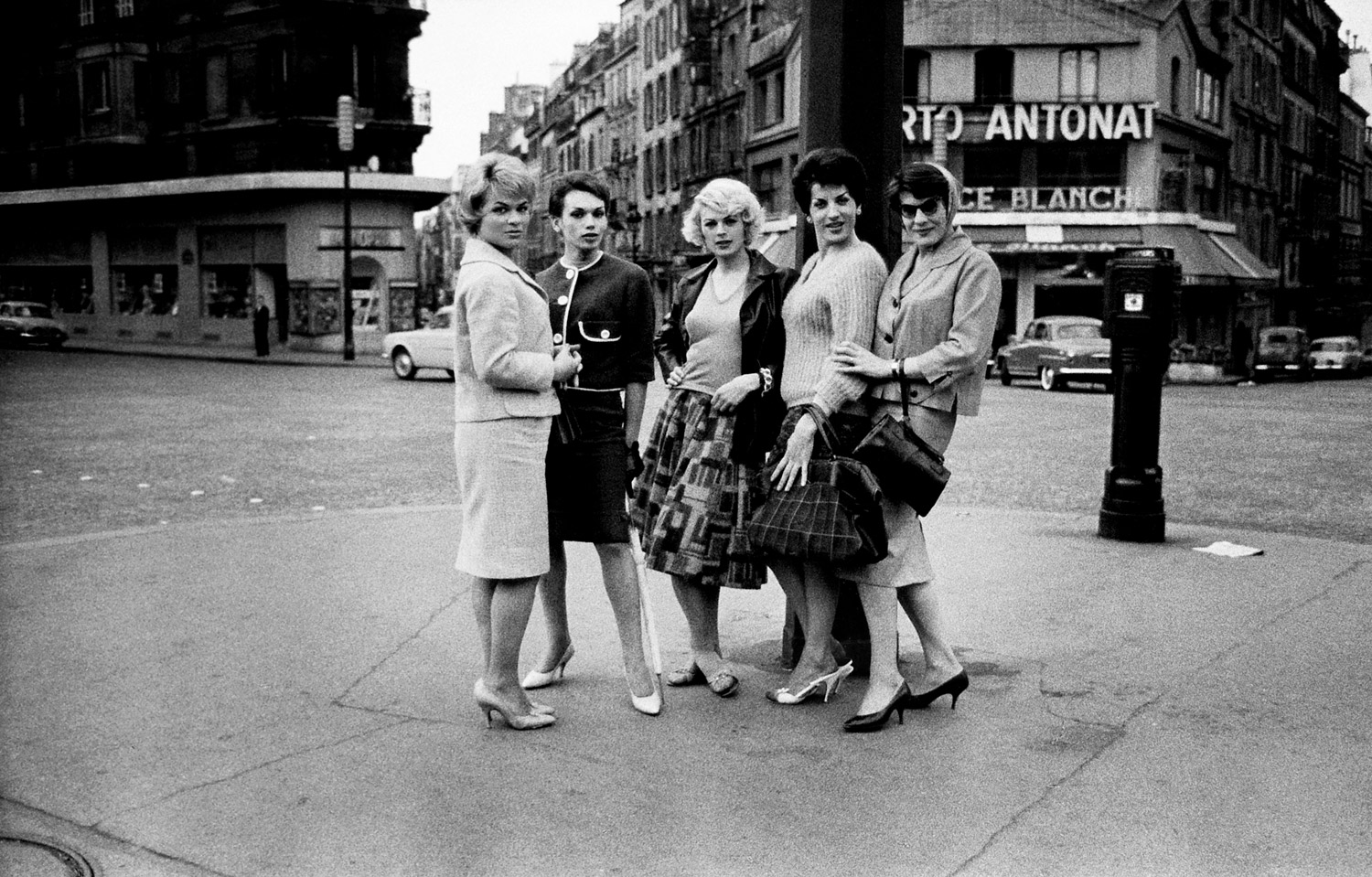

In 1959, Swedish-born photographer Christer Strömholm moved to the Parisian neighborhood of Pigalle. There, during the darkest hours of the night, he would comb the streets, not as a voyeur, but as a participant of the night’s activities. In time he would meet and form intimate relationships with the transsexuals of Place Blanche. At that time, France was ruled by General Charles de Gaulle, the man who led the Free French Forces during World War II, and his wife Yvonne, who were both devout Roman Catholics. Tante Yvonne (Aunt Yvonne), as she was known to the general public, held old-fashioned conservative views that created a puritanical atmosphere. As a result, Strömholm’s “friends of Place Blanche” found solace in each other, most having escaped a life of misconception. These friends, biologically born as men, were forced to flee their hometowns in search of a place where they could be at ease with themselves.

But life in Paris was just as difficult. It is a widespread belief that it was Aunt Yvonne’s influence on her husband that brought forth the reinstatement in of a 330-year-old draconian law that punished landlords who allowed prostitutes to work on their premise with the forfeiture of their property. There was no social security in Paris nor any chance of getting hired if the name on a person’s identification card did not match his appearance. Without the help of society, these ladies of the night had little choice but to sell their bodies in hopes of earning enough money to make it to the hospitals of Casablanca where they could physically be transformed into women.

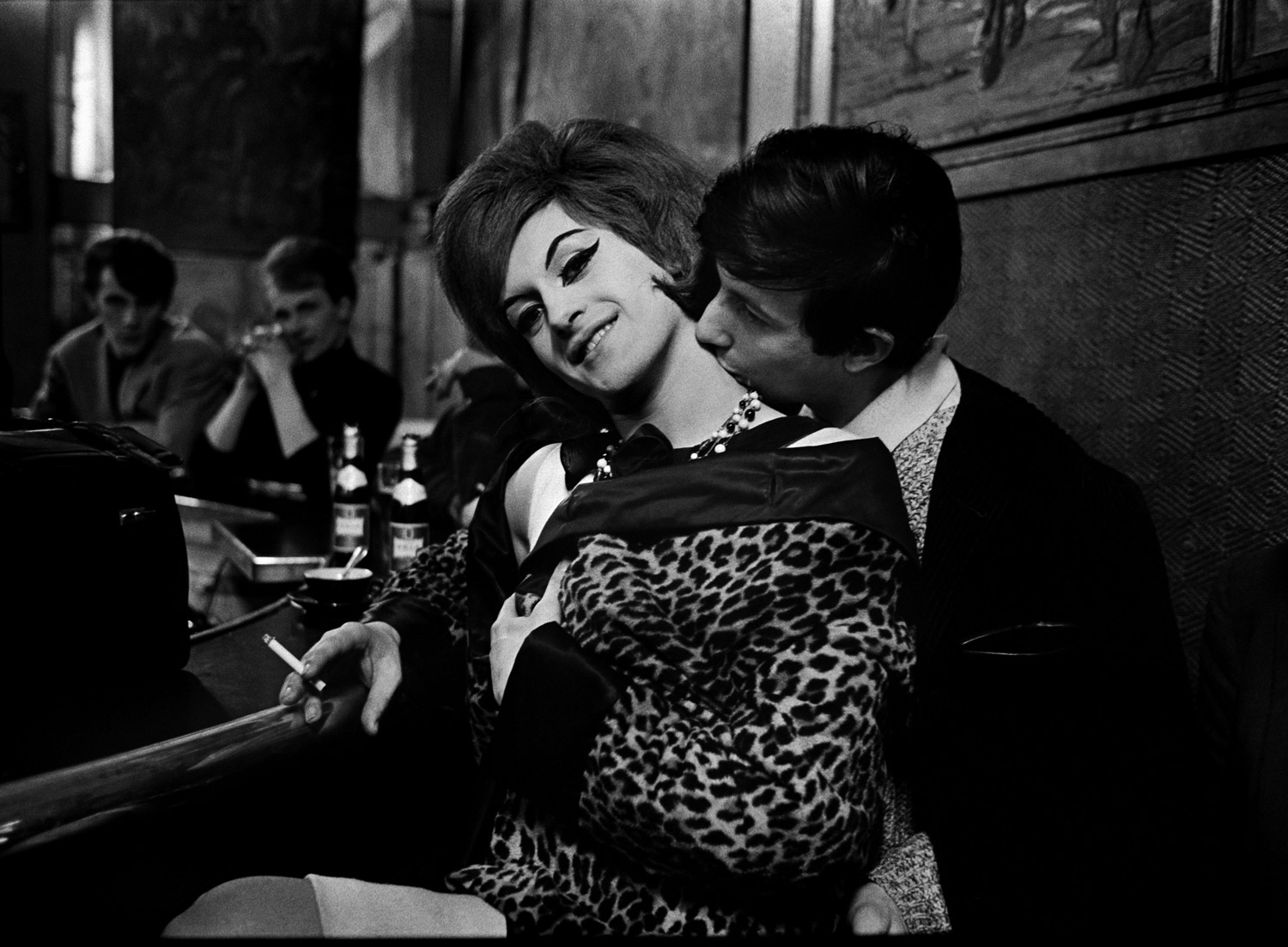

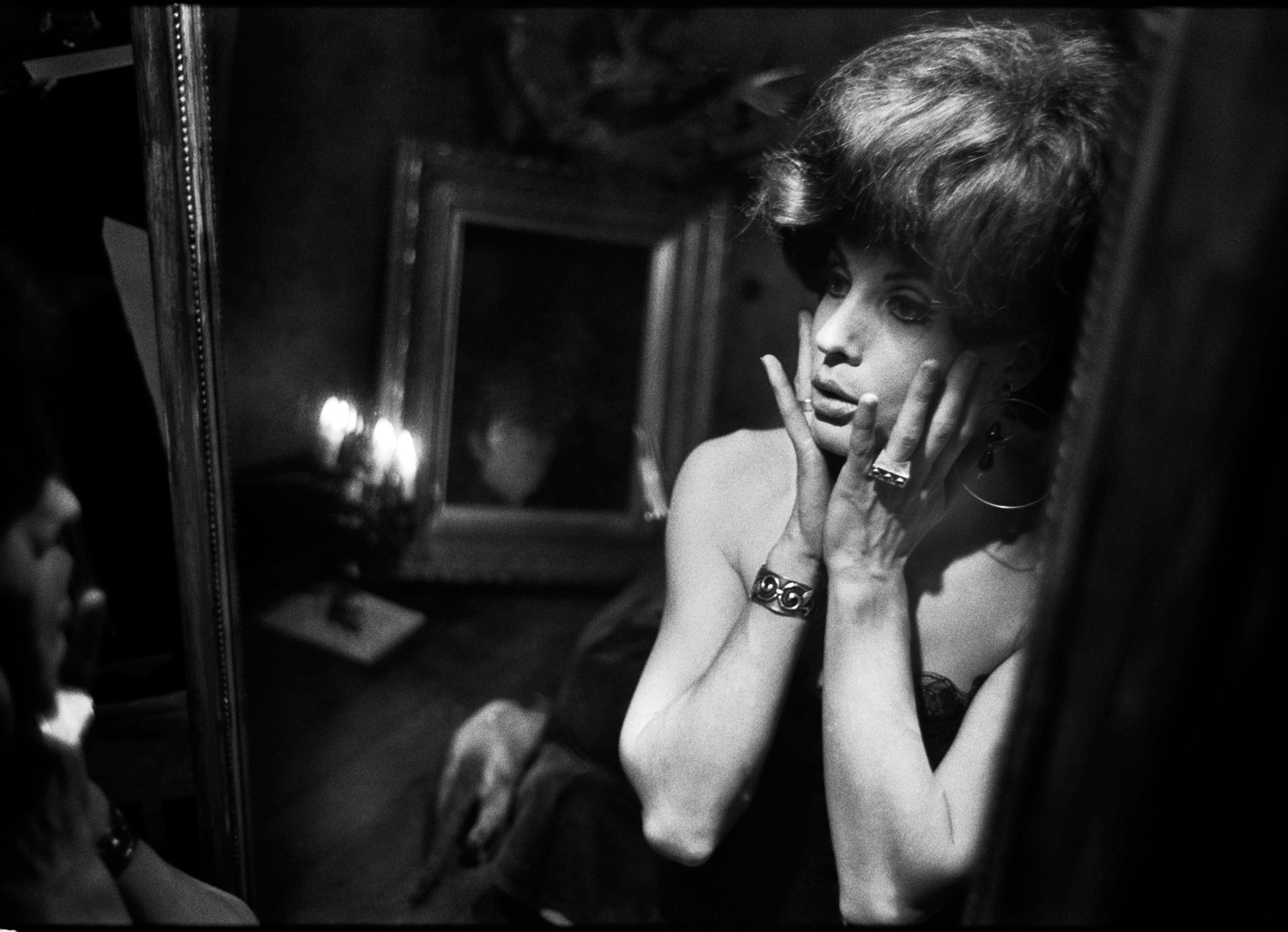

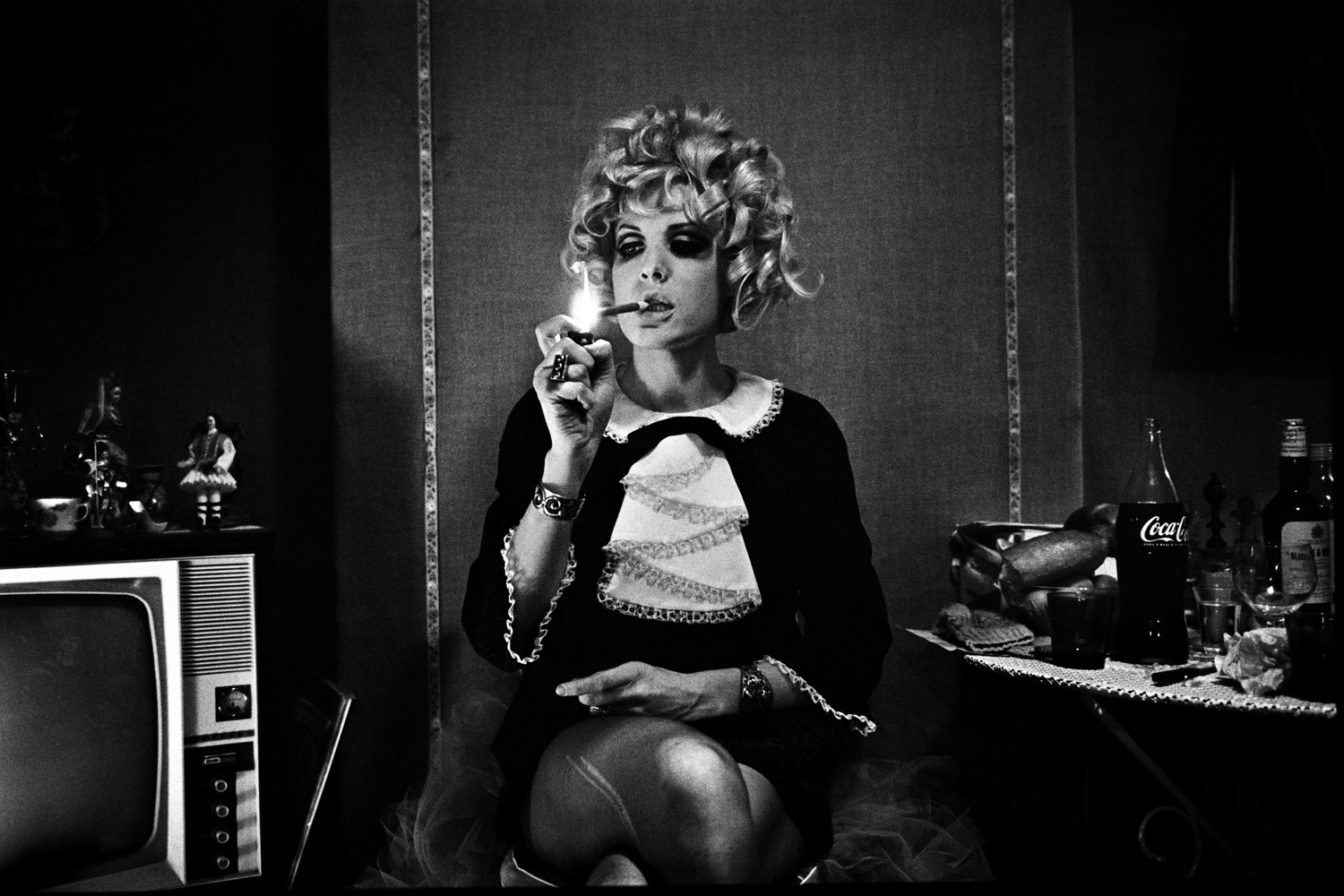

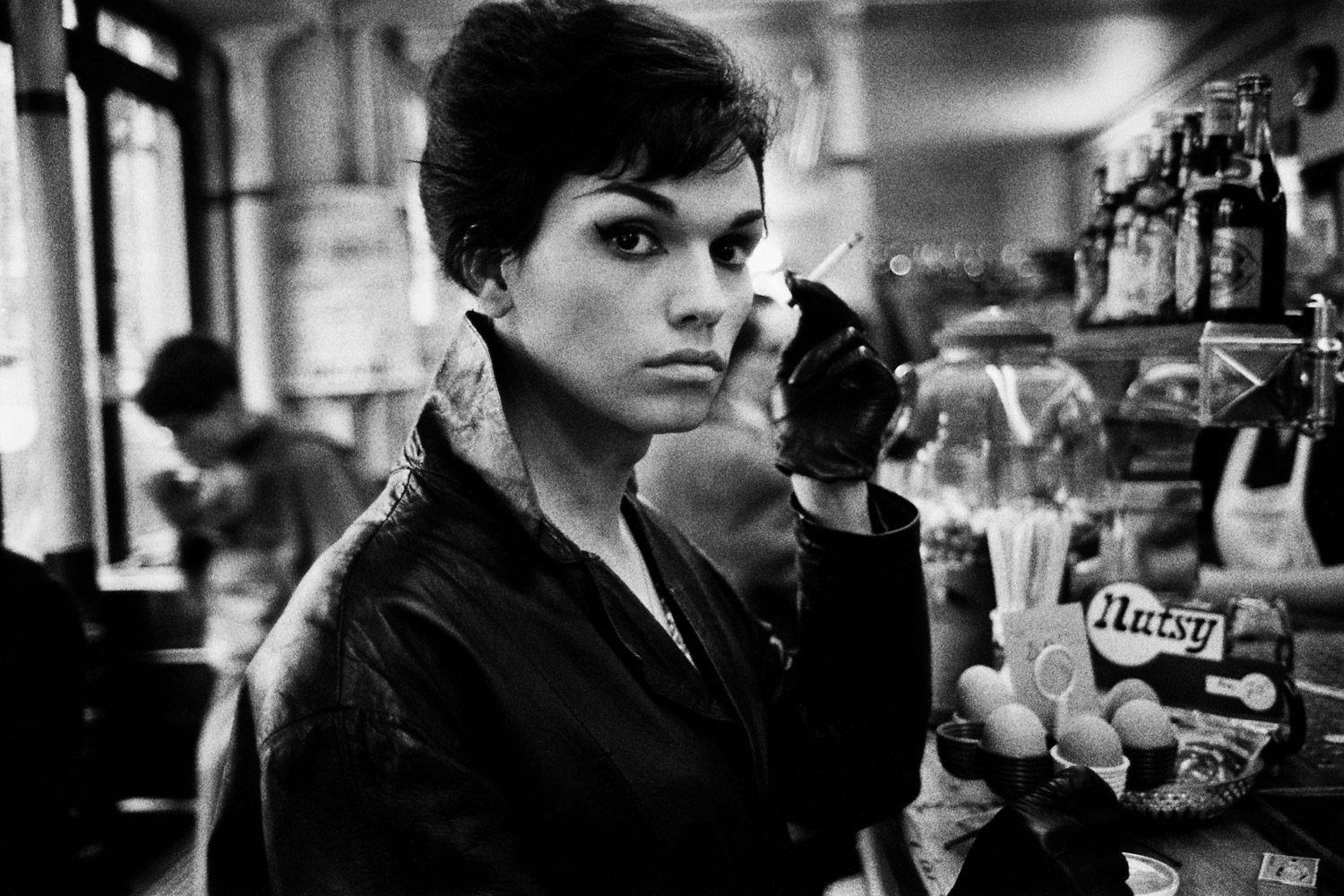

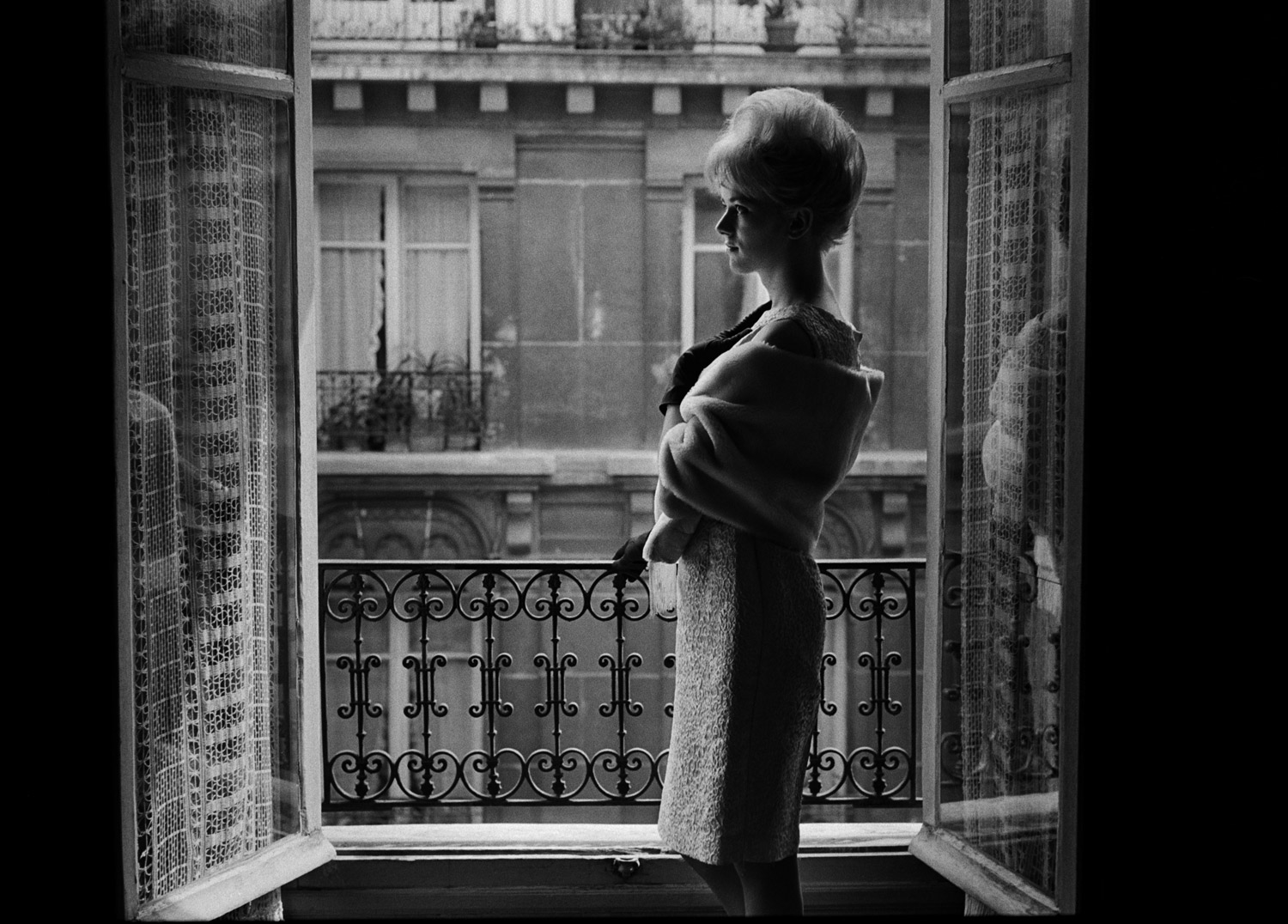

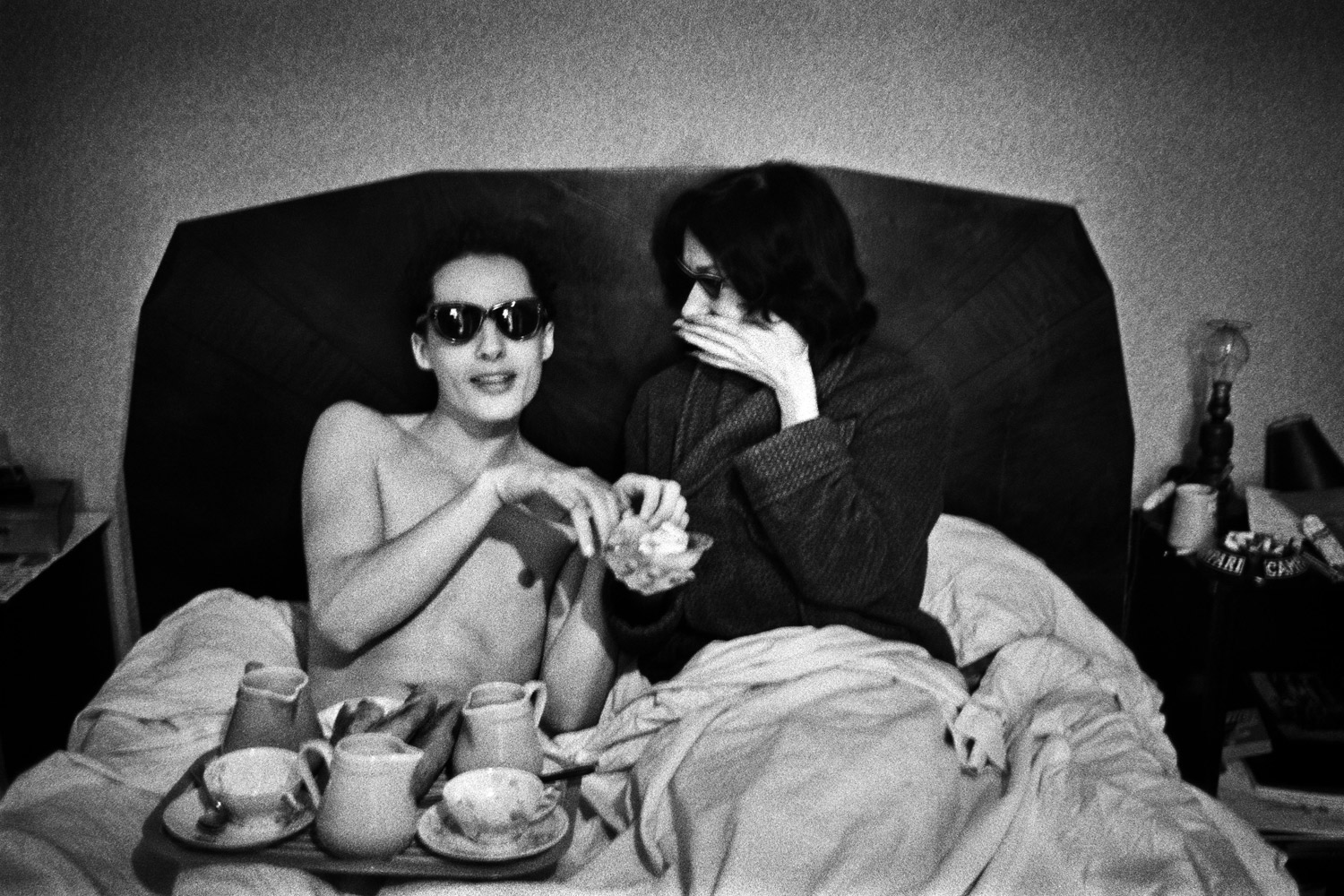

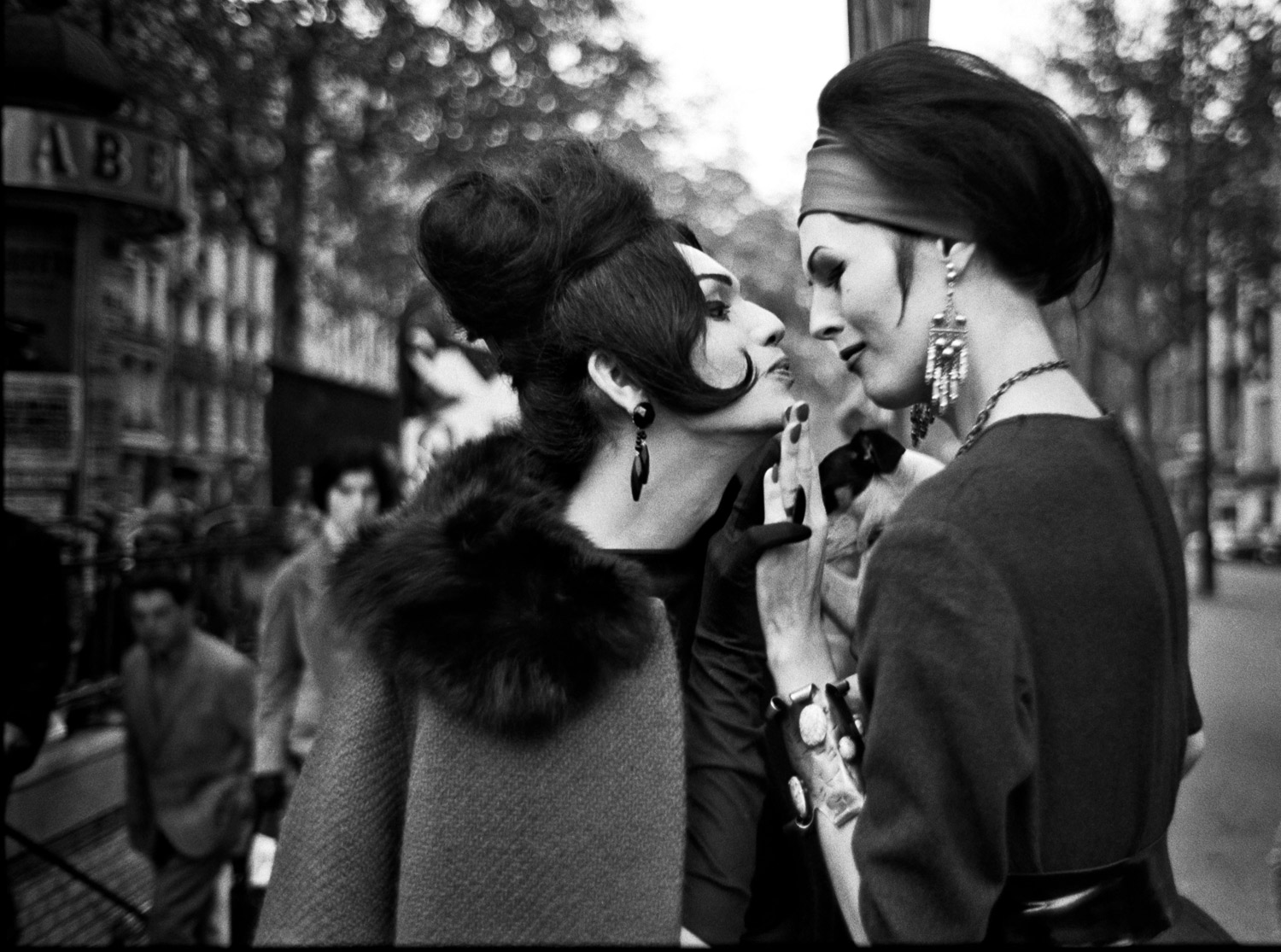

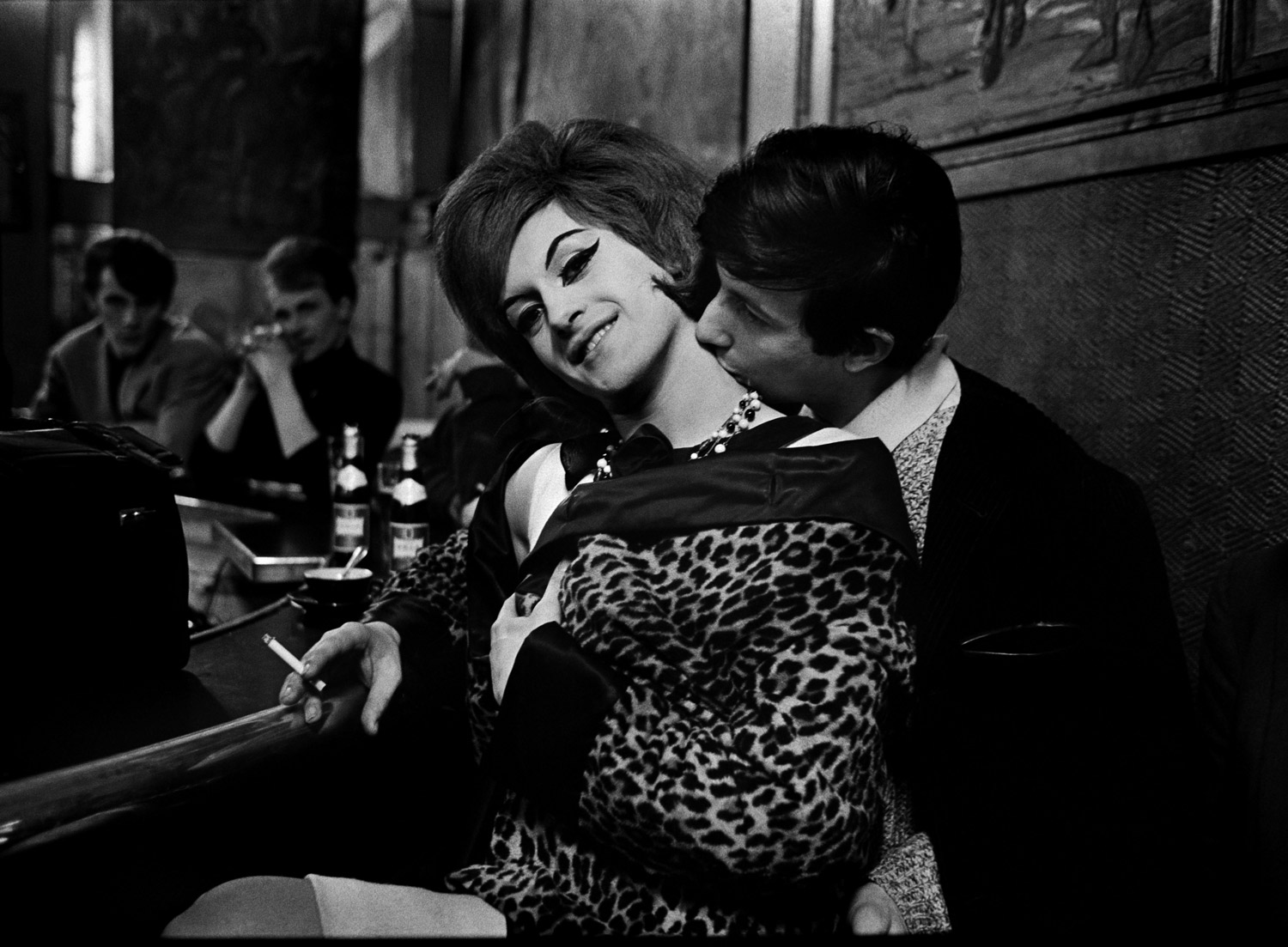

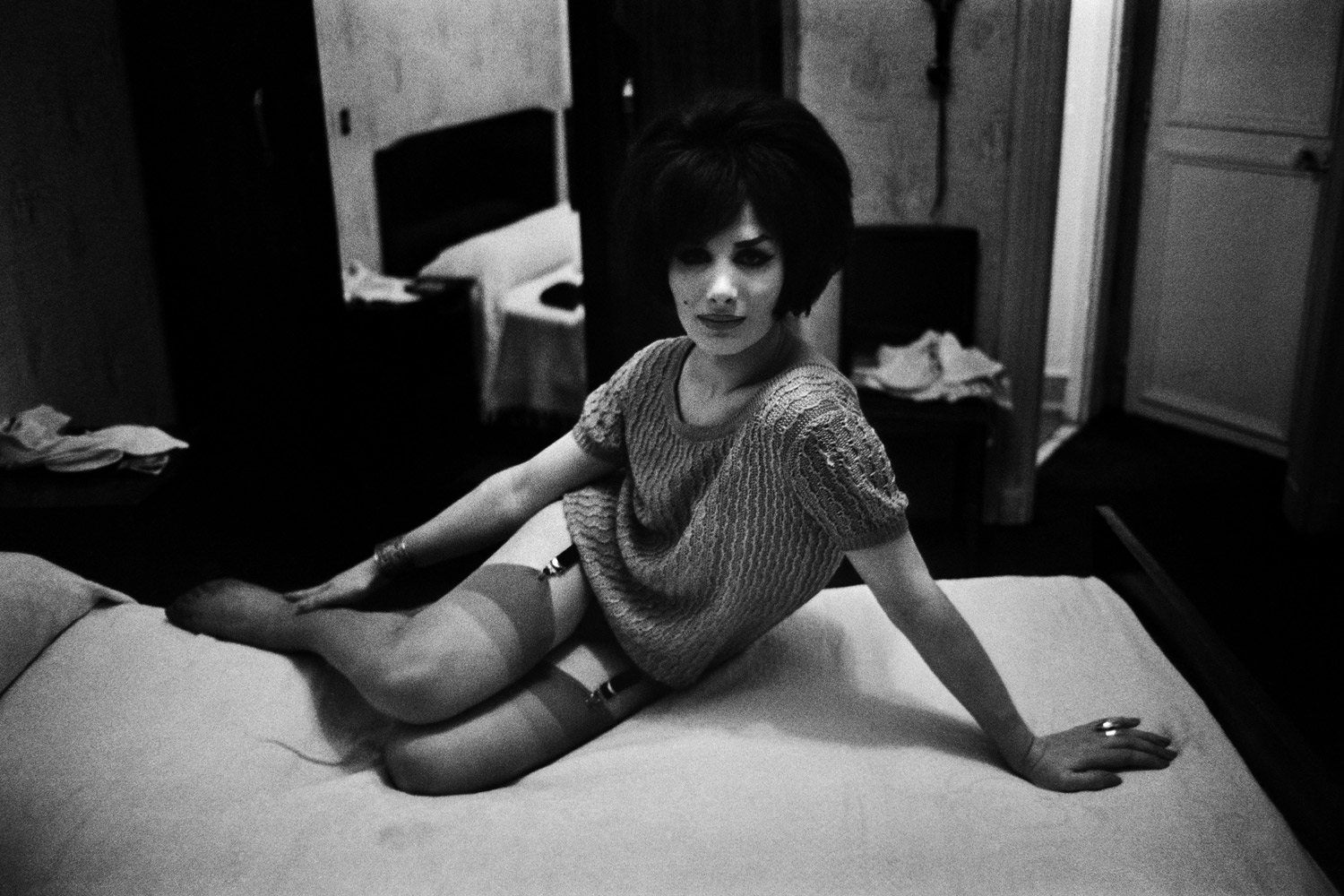

The photographs in Les Amies de Place Blanche, a new re-edited version of the original book published in 1983, demonstrate the photographer’s compassion for these women and the intimate friendships he developed during the time he lived in Paris’ red light district. They do not reflect the cruelty that these women endured, perhaps because in their own world, life was that much brighter and hopeful. After spending all night working the street corners, Strömholm and his friends would gather at the brasserie on the place Blanche and order hot chocolate and walk quietly back to their hotel rooms. The next day Cobra, his next-door neighbor at Hotel Chappe, would knock on the wall to announce that coffee was ready just as dusk was breaking. Crumbs would fall into the creases of the sheets as they shared their thoughts in bed.

Living side by side with these women, Strömholm perfected taking photographs at night. As these women got ready for work, so too did the photographer. With his Leica, Tri-X films and a pipe in his hand, he would walk down the boulevard from place Pigalle to place Blanche ready to capture fleeting moments of beauty.

Les Amies de Place Blanche, will be published by Dewi Lewis in the United Kingdom this February, and in the United States this March.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com