“Ultimately, photography is subversive not when it frightens, repels, or even stigmatizes, but when it is pensive, when it thinks.” -Roland Barthes

If I follow the train of thought of Barthes as ascribed by the quote above, Robert Adams would be the American “protest” photographer of my choice. Several of his books—The New West, What We Bought, and Our Lives, Our Children: Photographs Taken Near the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant—use the weapon of subtle metaphor to warn against expansion into nature, greed and consumerism, and the endgame of all, nuclear annihilation. The idea of photography taking the task of exposing the wrongs of the world as a kind of subversive “protest” has a long history. I think of the montages John Heartfield in the thirties, or Gilles Peress’ reportage on genocide in Rawanda from the nineties. These are photographs with content that declare a stand in opposition to the status quo. The recent Protest Box, compiled by the British photographer Martin Parr, just published by Steidl, contains five facsimile reprints of some of the most important books of protest produced within the history of the photobook.

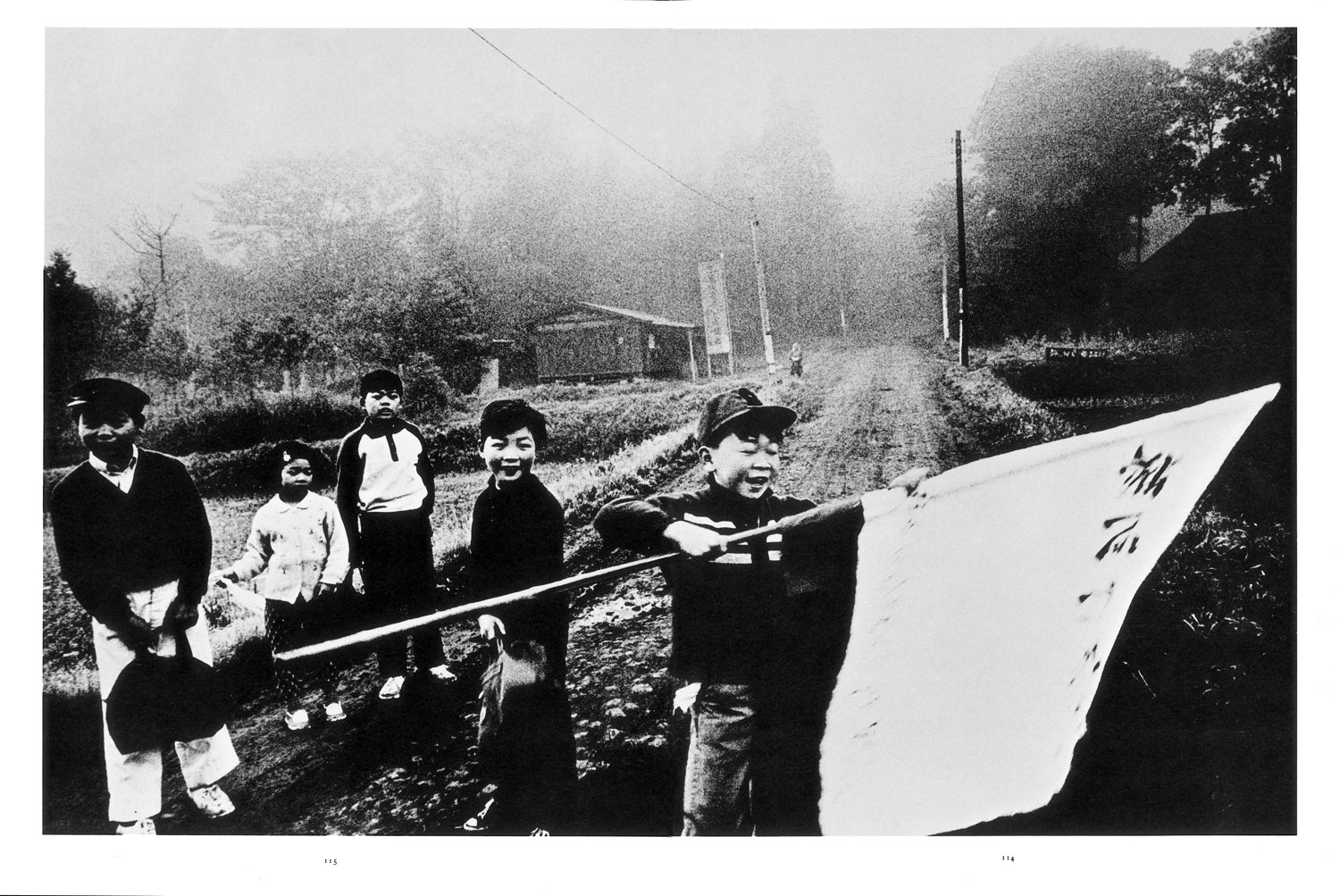

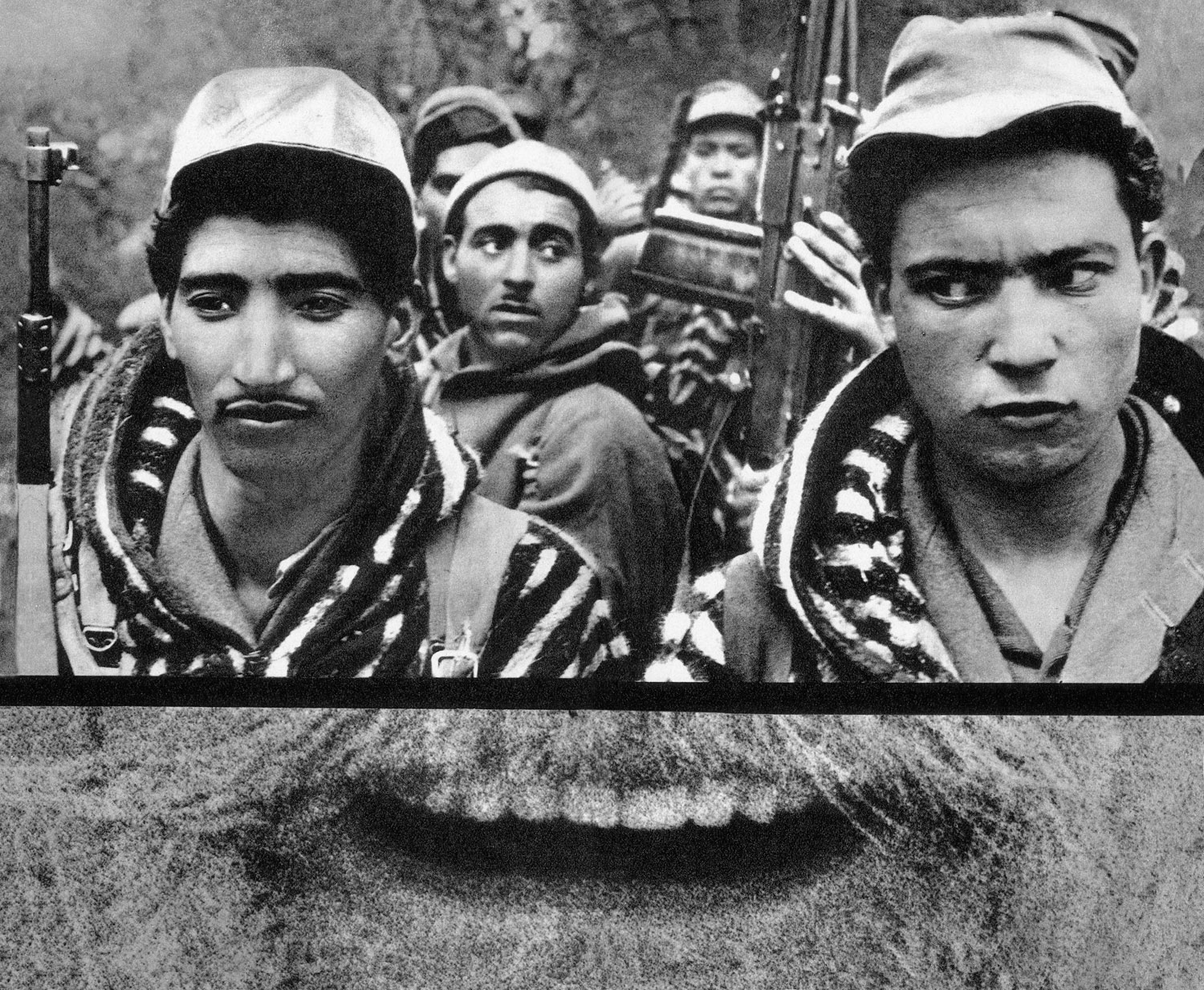

The first book by the German photographer Dirk Alvermann has to be, in my opinion, one of the most exciting discoveries in photobooks during the last decade. Algerien/ L’Algerie, published in 1960, takes as its subject the bitter independence struggle of Algerians against French colonialism. Shot in black and white with a distinctly pro-Algerian tenor, Alvermann constructs his narrative through brilliant design techniques that take their cue from the cinematic montage of filmmakers such as Sergei Eisenstein. With the flow of radically cropped images and image repetition along with page layouts that appear at times almost surreal, Alvermann seemed free to push the boundaries of the material to its most provocative point.

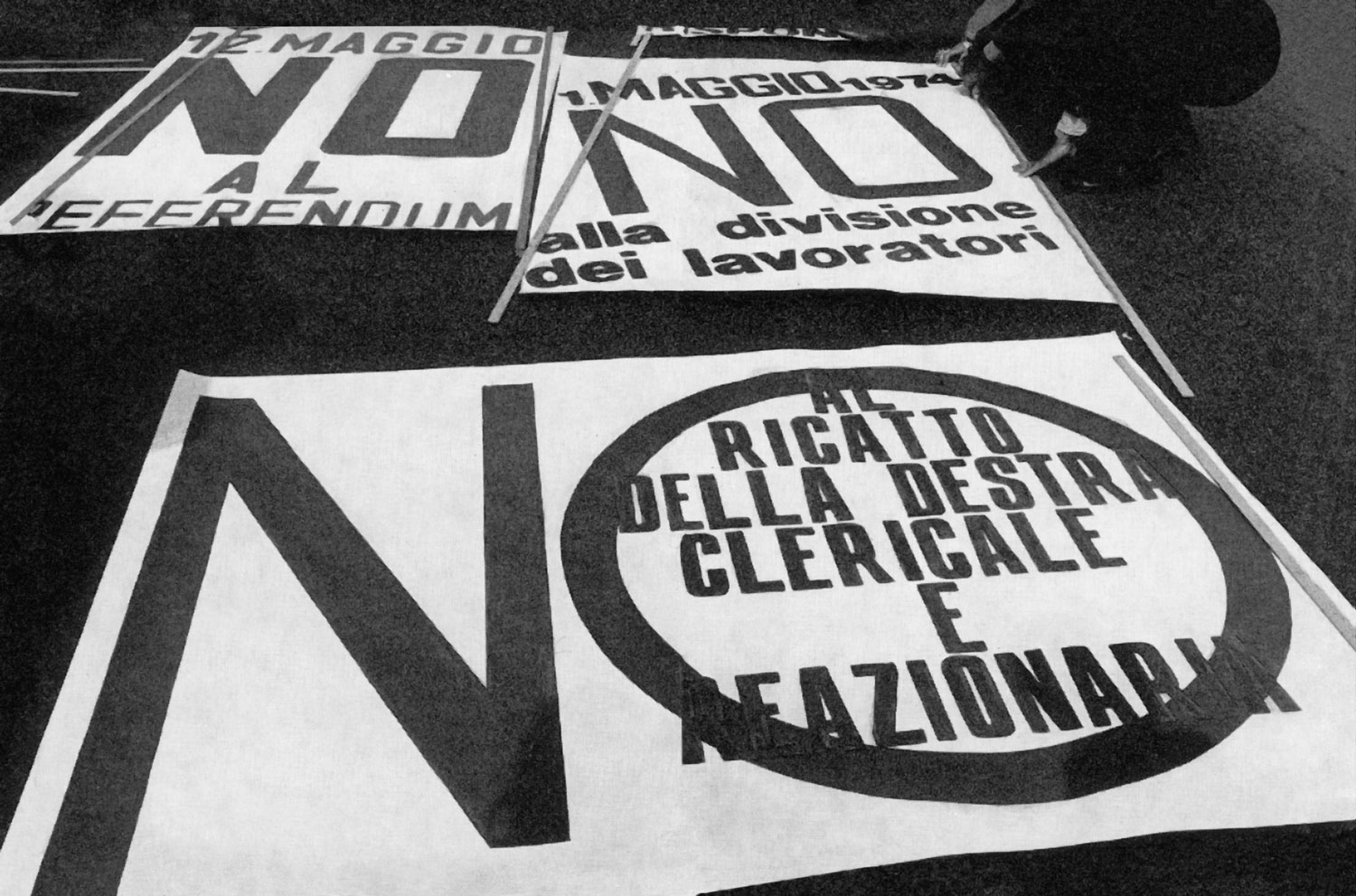

The second book, No Images by Italian photographers Paola Mattioli and Anna Candiani, is the story of the ‘No’ campaign, where conservative forces backed by the vatican were attempting to overturn “The Fortuna Law” passed in 1970 that allowed for divorce in Italy. The first abrogative referendum in the history of the Italian Republic was held on May 12, 1974 resulting in a 90 percent turnout at the polls, where 59.3 percent voted against the repeal of the law. This tiny photobook, about half the size of a postcard, pulls together a string of images where the word ‘no’ appears on walls, banners, posters and fliers. It has almost a conceptual tone that meditates on the word that is the basis of any protest.

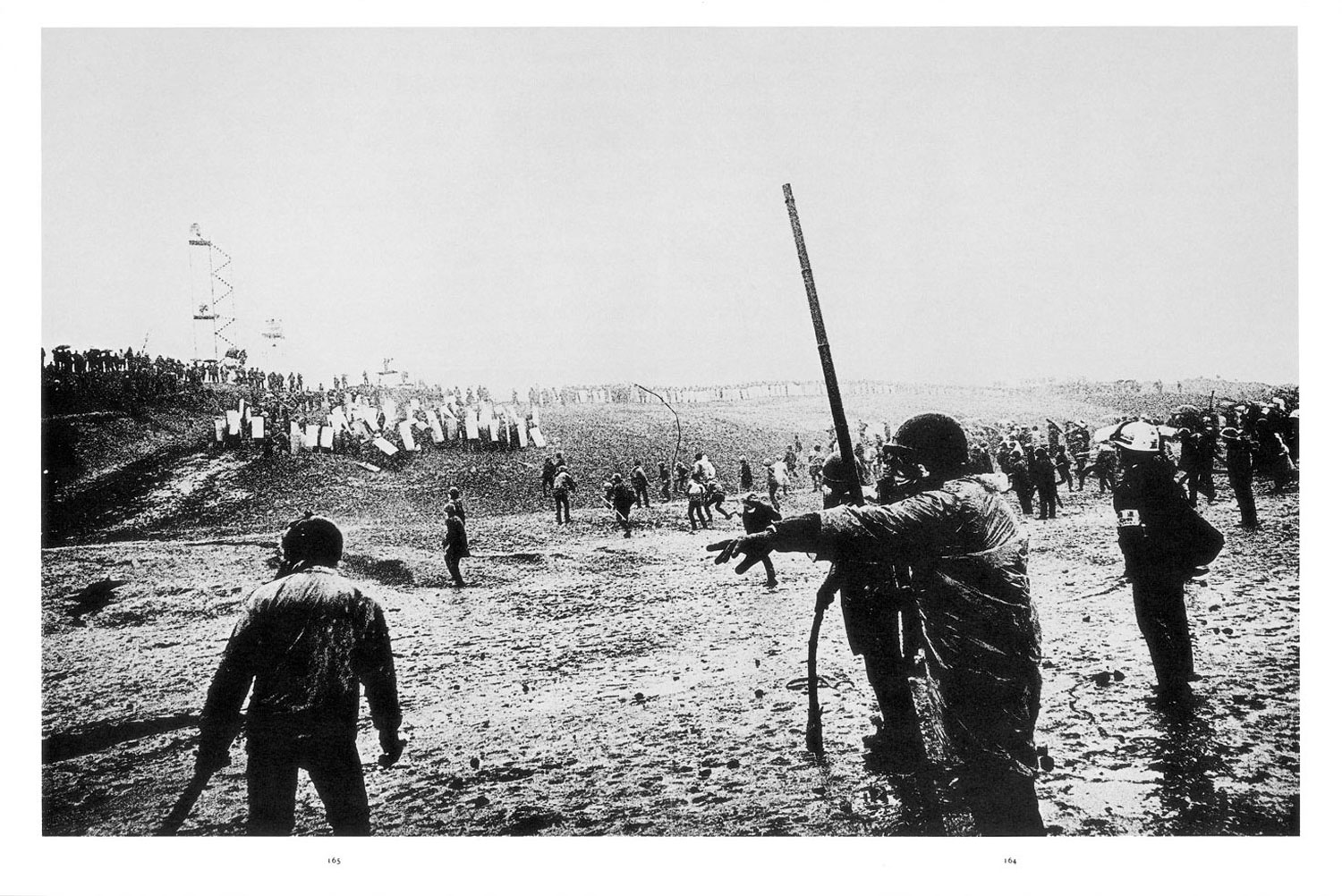

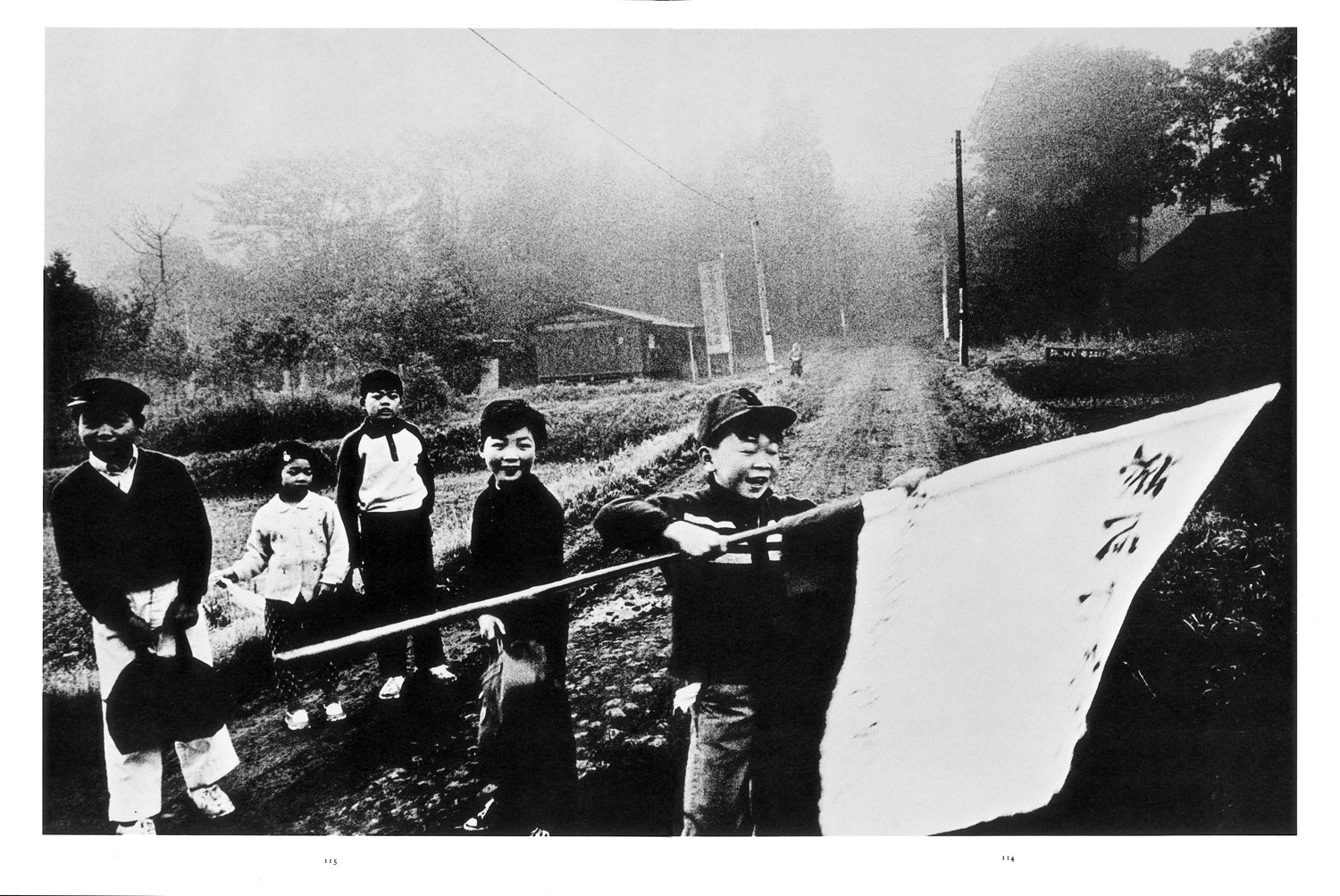

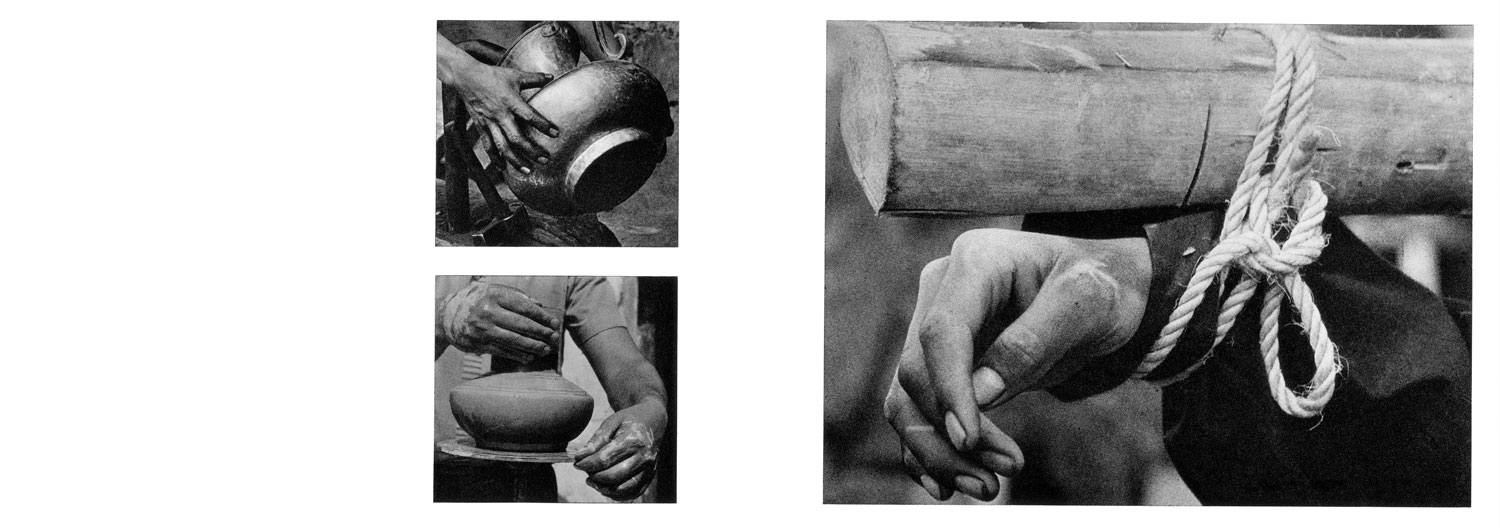

The next book, stemming from Japan in 1971, Kazou Katai’s Sanrizuka documents aspects of one of the longest and most highly charged Japanese protest issues: the building of the Narita Airport which threatened the livelihoods of farmers in the surrounding rich agricultural region including the village of Sanrizuka, from which the book takes its name. Shot in grainy black and white and evoking a calmer tenor to the blurry and contrasty ‘Provoke’ style, Katai concentrates not on the violent clashes of the struggle but instead the disruption of the centuries-old way of life for the farmers. His concern is reflected in the book’s afterword as he comments, “This is no longer a place suitable for human life…How to sow the thoughts of these murdered villages and their vengeful spirits into this very earth.”

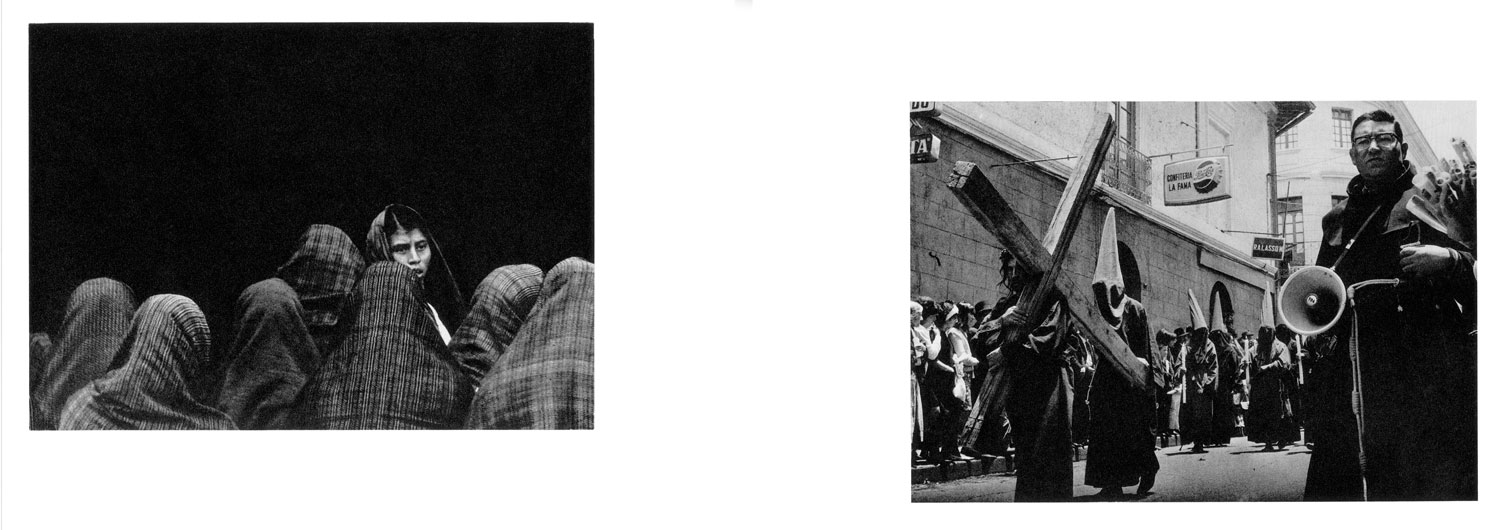

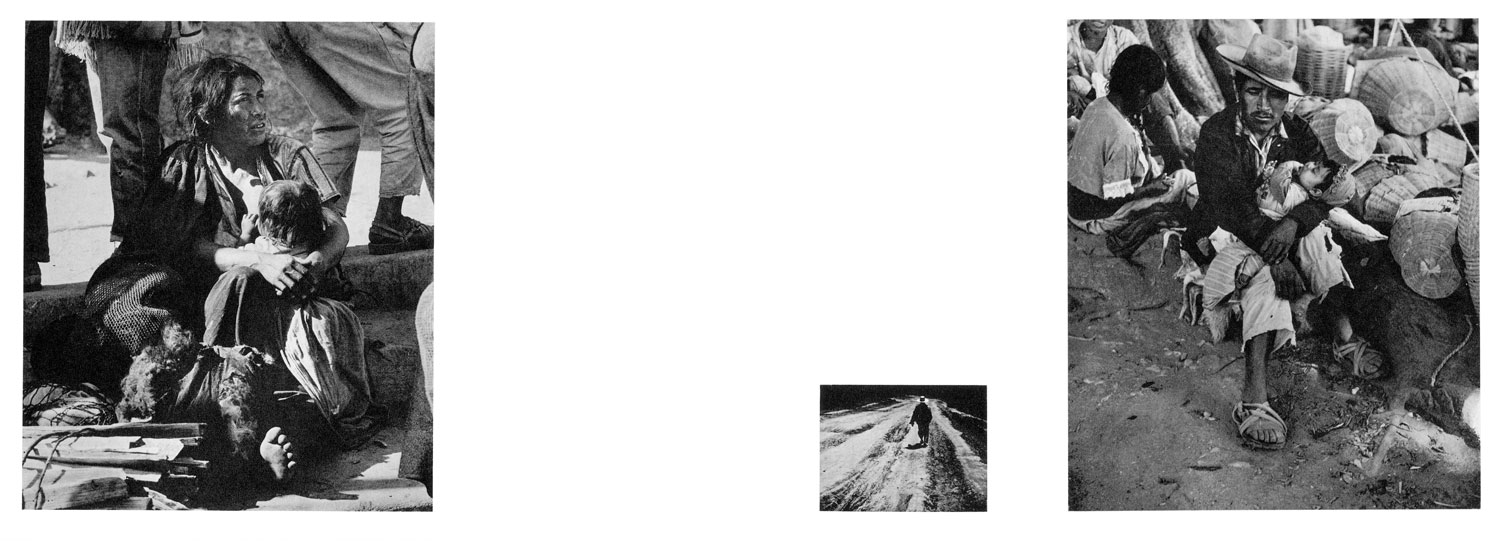

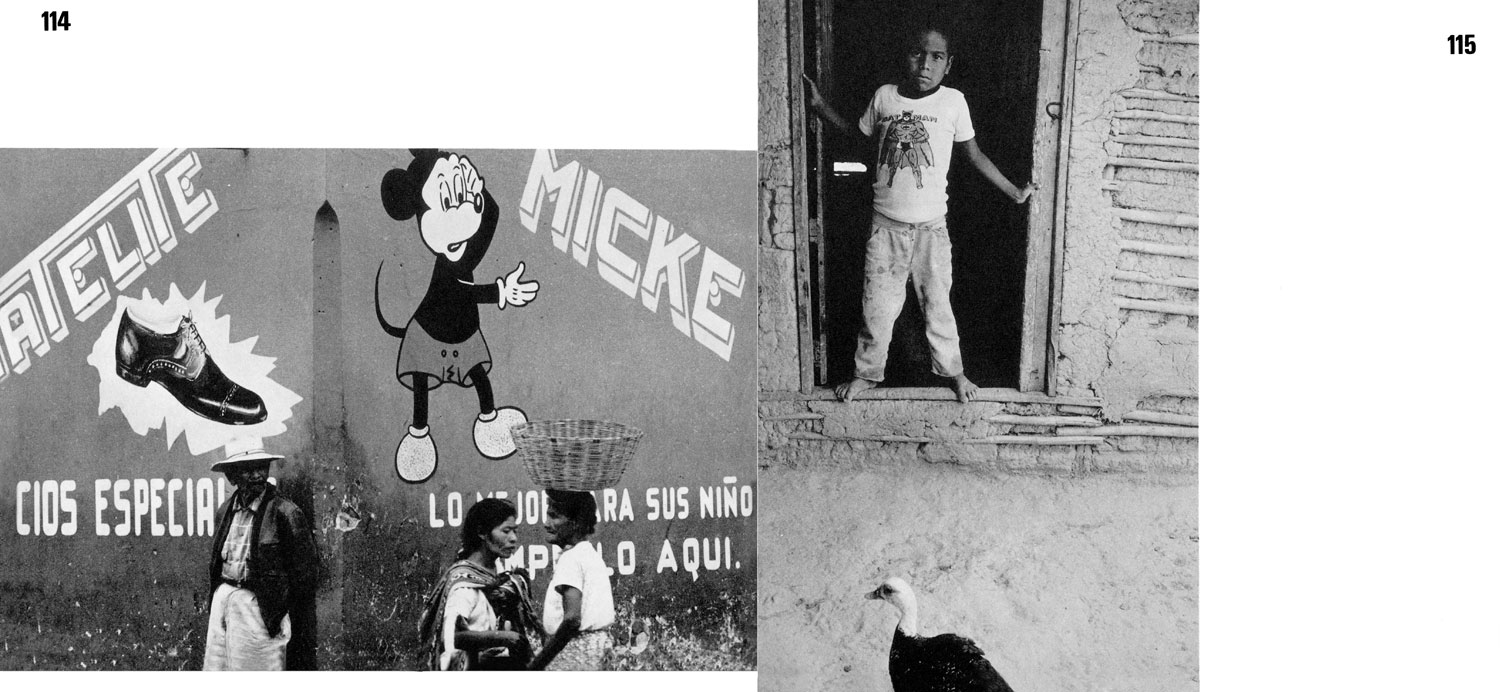

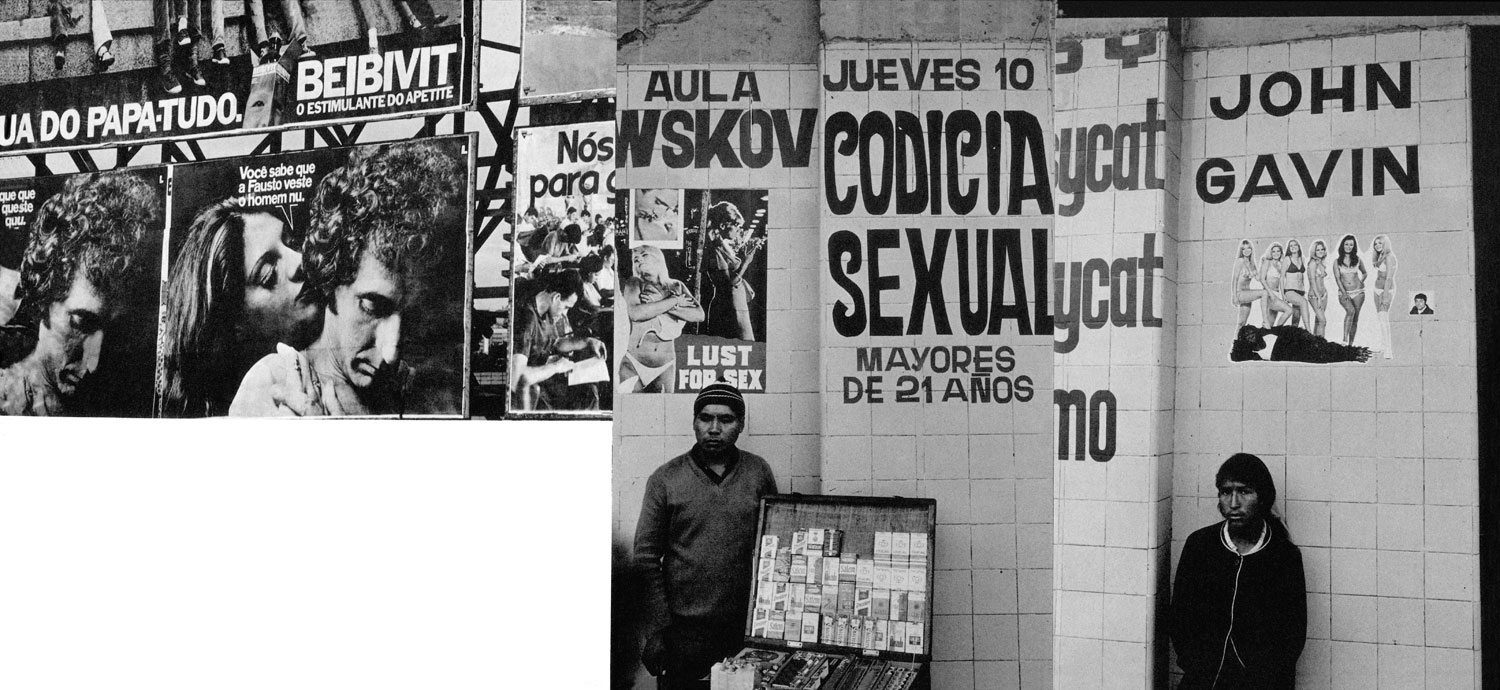

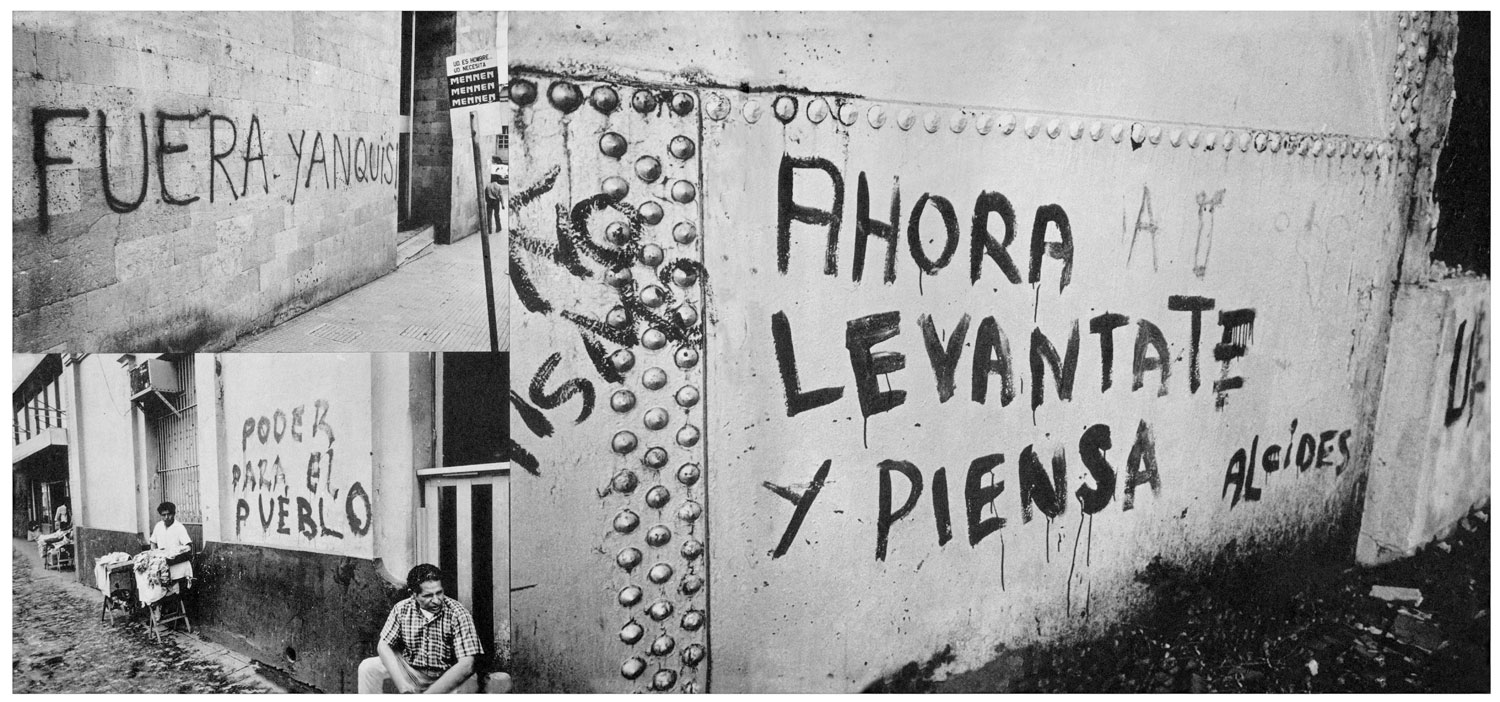

Two Latin American books, Enrique Bostelmann’s America; A Journey Through Injustice (1970) and Paolo Gasparini’s To See You Better, Latin America (1972), close out The Protest Box set. Both Bostelmann and Gasparini are essentially street photographers who direct their indictments towards the ruling classes, the history of colonization, the injustices faced by the poor and the spread of consumer culture creeping down from the North.

Enrique Bostelmann’s Journey travels not only through Latin America, but history, as the photo sequence goes back in time celebrating older pre-colonial rituals and ways of life. Meanwhile, a repeated motif of a single image of a lone figure trodding down a dirt path seems to say progress for the indigenous is at a complete standstill.

In Paolo Gasparini’s To See You Better, Latin America is also a street level journey but one that contrasts graphic text pieces within the layouts that often mock photographs of fantastical advertising imagery on billboards and building walls. Its complex visual strategy makes an absurdist collage of reality and fantasy all the while asking ‘who’ can bring progress towards a more equitable socialist society.

It is interesting to note that four of the five books were produced within three years of each other. The late 60s early 70s saw much in the way of issues to protest and these six photographers are but a handful from that era that felt the need to document with intent. With this Protest Box, we can take a fresh look at these few voices that have remained muffled within history’s bookshelves.

The Protest Box by Martin Parr is published by Steidl.

Jeffrey Ladd is a photographer, writer, editor and founder of Errata Editions. Visit his blog here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com