They went by several different names. James Atherton was a “news photographer” while Tim Hetherington preferred “image maker.” We just call them photographers. They make images, yes, often connected with the news. But they actually record the world–in all of its beauty, horror, pain and confusion–at a particular time and place.

For three of the photographers who were killed covering the civil war in Libya this year, the uprising to oust Muammar Gaddafi was far from their first experience in combat. Anton Hammerl, a South African who lived in London, documented violence in South African townships before the 1994 election. After years far from the sound of the guns, Hammerl traveled to Libya and went missing in Brega on April 5, along with two other journalists. Only when the other two were released by Gaddafi forces did Hammerl’s family learn that he had been killed.

The news would come more quickly for the families of Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros. On April 20, a mortar round crashed in the middle of a group of photographers covering the fighting in the city of Misrata. Hetherington and Hondros both died of their wounds. Hondros had covered Liberia and Iraq, among other conflicts, including the 2003 photo of a Liberian militia commander jumping elatedly in the air after firing a rocket-propelled grenade at rebels holding a key bridge in Monrovia. Hetherington’s image making would take him to Sierra Leone and Liberia, chronicling conflicts no one wanted to talk about. He gained fame for Restrepo, a brilliant, agonizing documentary film he made with journalist Sebastian Junger that told the story of a company of American paratroopers during a year of nearly constant combat in Afghanistan. Only months after being nominated for an Oscar for the film, Hetherington was back where the bullets were flying and the mortars were landing, giving his life to tell stories few want to see, but none can afford to ignore.

Jerome Liebling was a true product of the greatest generation, who grew up in New York during the Great Depression. He fought in North Africa and Europe during World War II as a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne. In spite of the carnage of war he witnessed, or perhaps because of it, Liebling trained his lens on the poor, the hungry and the forgotten. He wanted to “figure out where the pain was,” he once said, “to show things that people wouldn’t see unless I was showing them.” Yale historian Alan Trachtenburg wrote that Liebling was a “civic photographer,” but he was also a gifted teacher, serving first as a professor of photography at the University of Minnesota, then founding the film, photography and video program at Hampshire College in 1969.

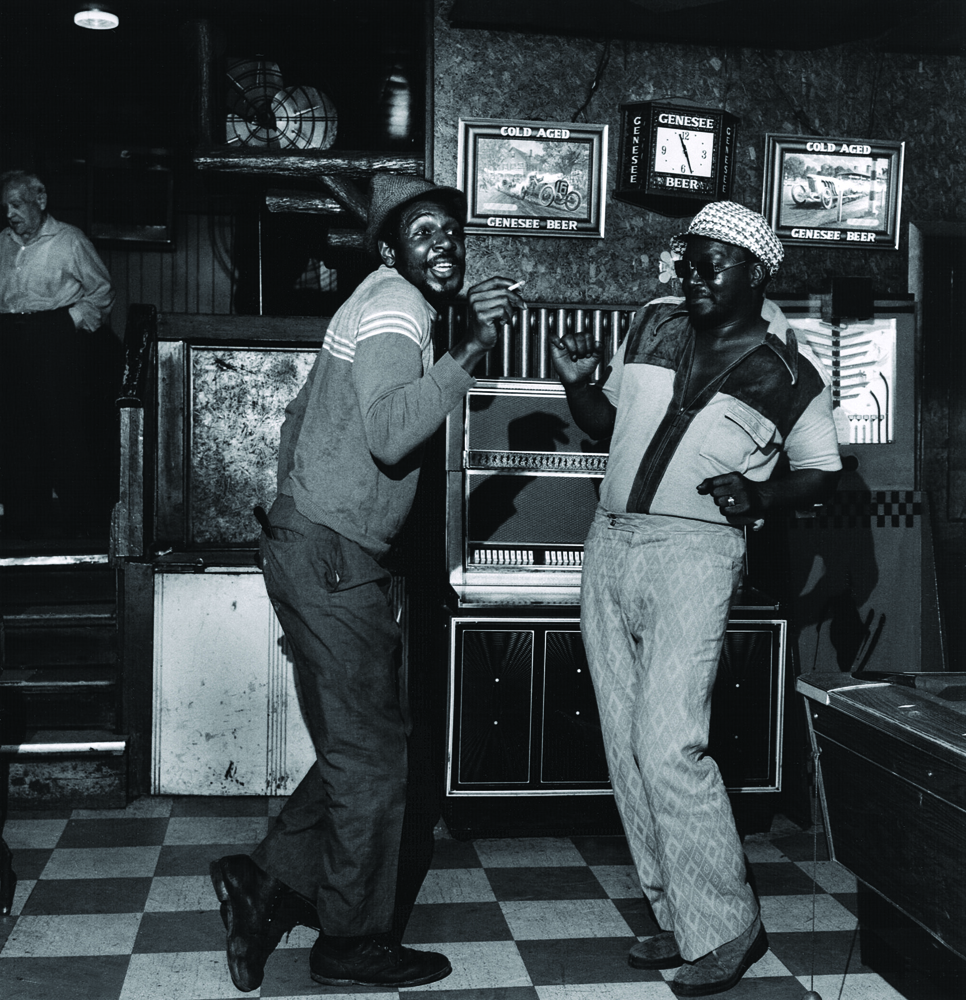

The plight of the poor not only drove Milton Rogovin to document their struggles, it also led him into politics. While working as an optometrist in New York during the Great Depression, Rogovin began taking classes at the New York Worker’s School and discovered the photography of Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine. His black and white images call to mind Walker Evans and Gordon Parks; his subjects were often people he met on the street, and he often had to convince them he wasn’t a cop or working for the FBI. “All my life I’ve focused on the poor,” he said in 2003. “The rich ones have their own photographers.” The poor he documented have their own place in history–most of Rogovin’s archive is collected in the Library of Congress.

It takes a second, looking at the cover of the famous “butcher” album to realize the moppy-haired youths are John, Paul, George and Ringo–the Beatles, who Robert Whitaker shot for the cover of the album Yesterday and Today. Maybe it’s the lab coats, or the raw meat; more likely it’s the dismembered dolls. Though the Fab Four’s handlers later replaced the image with a bland, hastily shot portrait, the cover survived as one of the most original–and strangest–music photographs in history.

A list of celebrities photographed by Jonathan Exley would alone take up an entire blog post: President and Secretary Clinton, Jerry Seinfeld, Marlon Brando, John Stamos (I’ll stop there). Yet Exley counted among his favorite subjects the brilliant, often kooky Michael Jackson. “Working with Michael was like working with a partner,” Exley said of photographing the King of Pop. His portrait of Jackson clad in a black scarf with the wind blowing his hair across his face, which was the cover of Rolling Stone’s tribute issue after Jackson’s death, captured the inner torment of Jackson’s final days like no other image or story possibly could.

After a career that spanned four decades during which he photographed Presidents from Truman to Nixon, James Atherton bristled at the term “photojournalist.” Instead, he wanted to be known as a “news photographer,” a somewhat anachronistic term that reminds us that photojournalists are, first and foremost, photographers.

Great photography is often a serendipitous event–the right photographer, shooting the right subject at the right time. Those elements came together for Barry Feinstein‘s 1966 image of Bob Dylan inside a car, as fans pressed their faces against the window to get a closer glimpse of the iconic musician.

When the 1973 Pulitzer committee awarded prizes for photography, the Feature Photography prize went to Brian Lanker, who died in March at 63. Lanker’s winning submission was a piece titled “Moment of Life’ for the Topeka Capital-Journal, which showed an exhausted, but elated mother as her just-born daughter was placed on her stomach. He would go on to make several arresting images of both everyday people and celebrities, including a beautiful picture of basketball player Wilt Chamberlain pretending to be asleep in his home in Bel Air.

LeRoy Grannis, once called by the New York Times “the godfather of surf photography” came late to the profession. At age 42, Grannis, who had surfed since his teens, took up photography on the advice of his doctor who said he needed a hobby to relax. Grannis became the lead photographer for Surfing Illustrated and in 1962 he co-founded International Surfing, which is now known as Surfing magazine. Grannis, who died in in February at 93, caught his last wave in 2001.

Long before he founded the photo agency Sipa, Goksin Sipahioglu was an accomplished and renowned photojournalist. A native of Turkey, he was one of the few “western” photographers in Havana during the Cuban Missile Crisis. He covered riots in Paris and while on assignment at the 1972 Munich Olympics, he found himself chronicling the kidnapping of Israeli athletes by Palestinian terrorists. With the notoriety from that assignment, Sipahioglu founded Sipa, which along with Gamma and Sygma dominated international news photography until the digital age.

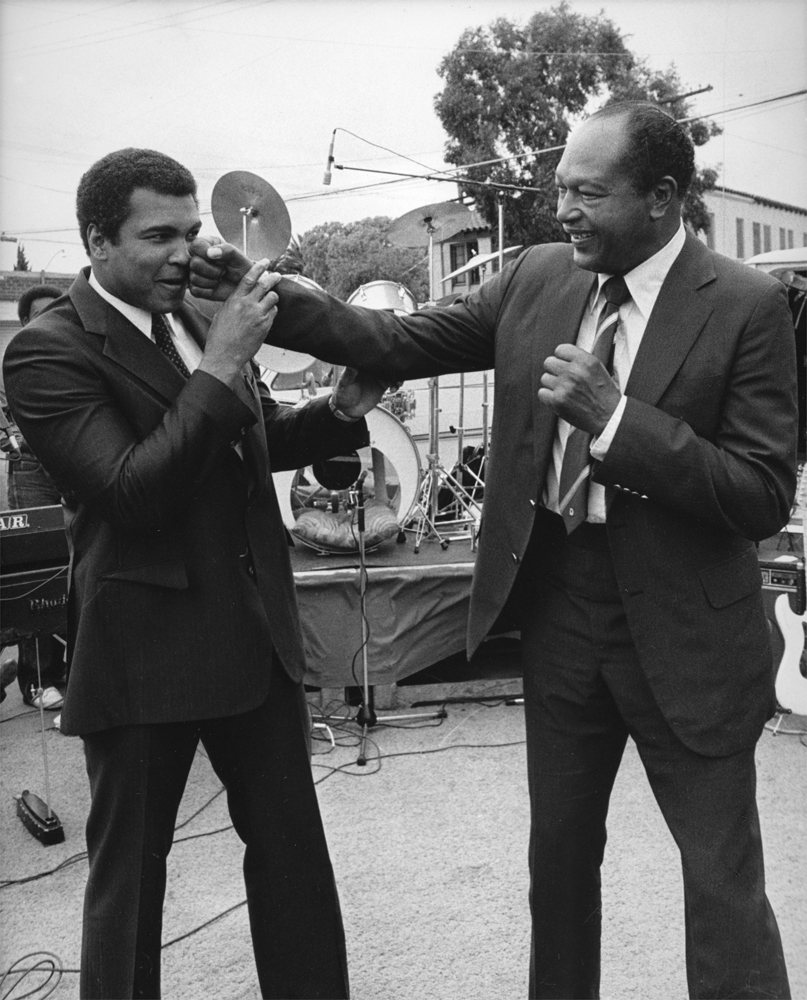

Guy Crowder seemed to have a knack for being where the action was. He was standing next to Robert Kennedy moments before the senator was assassinated. Crowder covered Martin Luther King, Jr’s funeral and Muhammad Ali’s popularity. Shunned by mainstream periodicals during the 1960s, Crowder took photos for the Los Angeles Sentinel, Wave newspapers and Jet and Ebony magazines.

Theodore Lux Feininger

Feininger was a renaissance man. As a student at the Bauhaus, a school for the arts in Weimar-era Germany, Feininger collaborated in experimental theater, played in the jazz band and was a painter. But it was as a photographer that he may have had his most lasting impact. Feininger captured images of the Bauhaus and the avant-garde Germany between the two World Wars that stands as a unique record of a time and group that have largely been forgotten by history.

As a child, Leo Friedman wanted to be an actor, so it was only natural that he was drawn to the theater. Over the course of his career as a photographer, Friedman photographed more than 800 Broadway shows for magazines and newspapers and often as the official photographer for the shows’ producers. He shot some of the most famous shows in Broadway history but one of his most famous photographs was a staged publicity shot of Carol Lawrence and Larry Kert running down the street smiling and holding hands for the original run of West Side Story.

Beginning in 1980, Lou Capozzola was a prolific photographer for Sports Illustrated. He shot the last time Wayne Gretsky skated on the ice in an NHL uniform in 1999, a behind the back, no-look pass from Shaquille O’Neal to J.J. Hickson in 2010 and thousands of hockey games. Capozzola, who died in August at 61, shot the Stanley Cup playoffs for his final assignment, where the Boston Bruins ended a 39-year championship drought. His photo of goalie Tim Thomas hoisting the cup became the cover of SI’s commemorative issue.

We lost great photographers this year. They photographed Presidents and popes, rock stars and rebels. They risked their lives, and some of them gave their lives, so that we can better understand our own, the place we inhabit, and more importantly, the areas of the world we would otherwise never see. —Nate Rawlings

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com