If there is a land above the seas that remains a last frontier for mankind, it’s Antarctica. A recent GPS mapping conducted by the British Antarctic Survey provided a reminder of how uncharted and unknown the vast white continent still is. When Antarctica’s hulking glacial landmass—icy and inhospitable—was spotted by 18th century British Captain James Cook, he remarked: “I make bold to declare that the world will derive no benefit from it.”

That proclamation did not ward away future journeys, though. An exhibition at the Queen’s Gallery in London’s Buckingham Palace marks the centennial of one of the last great episodes of the age of exploration. “The Heart of the Great White Alone” exhibits images taken from two separate expeditions: the ill-fated attempt by Robert Falcon Scott to reach the South Pole in 1911 and the slightly less calamitous (but no less dramatic) expedition undertaken in 1915 by Ernest Shackleton, whose ship foundered in Antarctic ice and whose crew escaped a frosty end only after one daring act of courage.

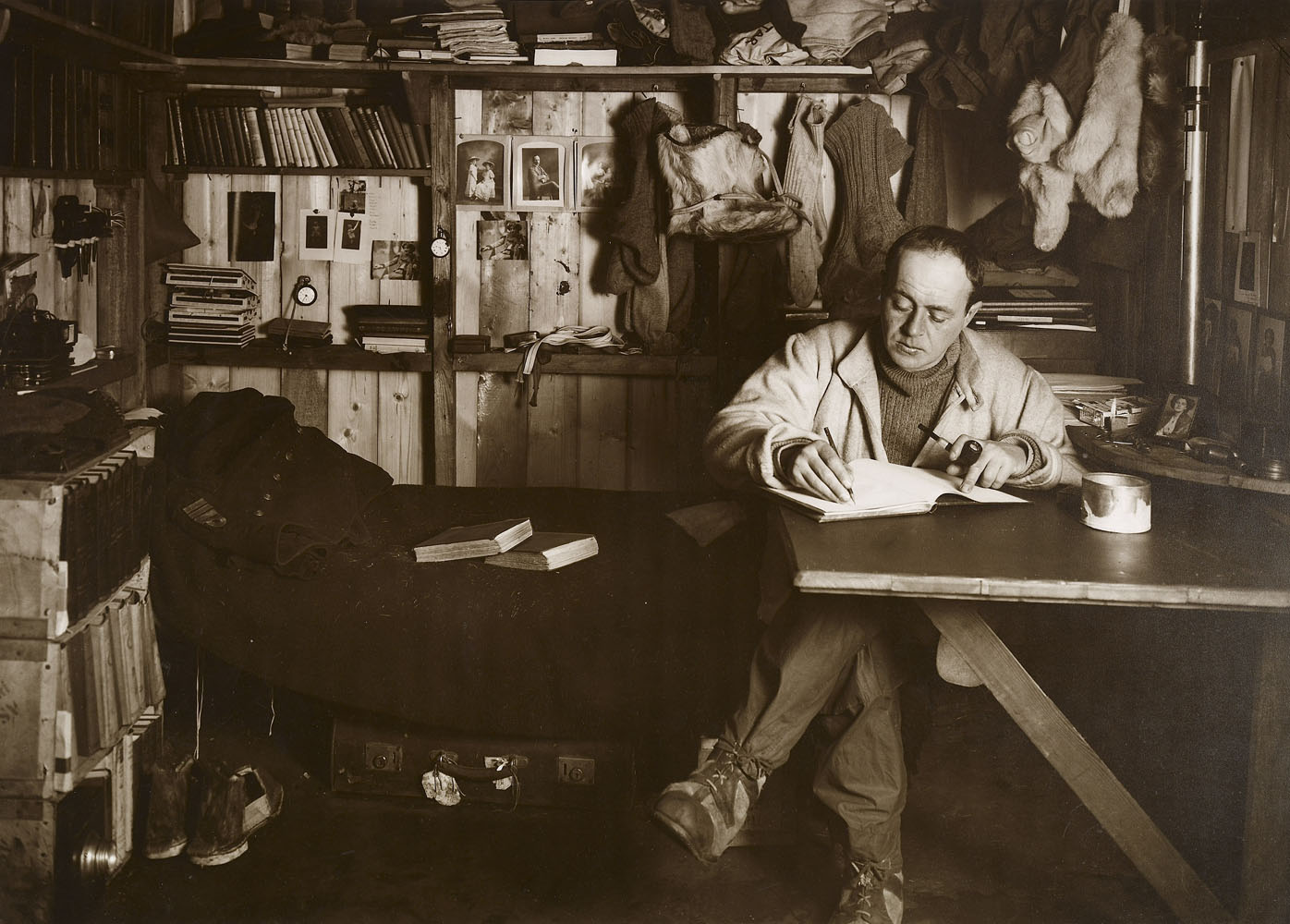

Accompanying Scott was Herbert Ponting, the early 20th century version of a footloose freelance photojournalist. The Briton’s peripatetic career had taken him from California to the naval battlefields of the 1905 Russo-Japanese war to treks across stretches of Asia. His photos retain a distinctly Victorian sensibility for landscape; Scott’s ship, Terra Nova, and members of his crew are dwarfed or eclipsed by the magnitude of the silent, icy world around them. Ponting was also captivated by Antarctica’s fauna and almost died in the maws of a pod of killer whales, which burst through sheets of ice near where the intrepid photographer had set up for a closer look. An entry in Scott’s diary records the moment: “It was possible to see the whales’ tawny head markings, their small glistening eyes and their terrible array of teeth — by far the largest and the most terrifying in the world.”

Ponting stayed behind with the main contingent of the expedition while Scott and a team of volunteers left their base camp in November 1911 to press toward the South Pole. Scott would never return, consumed by his quest to be the first to reach the Pole; he was beaten to the site by the Norwegian Roald Amundsen, who unlike Scott, lived to tell the tale.

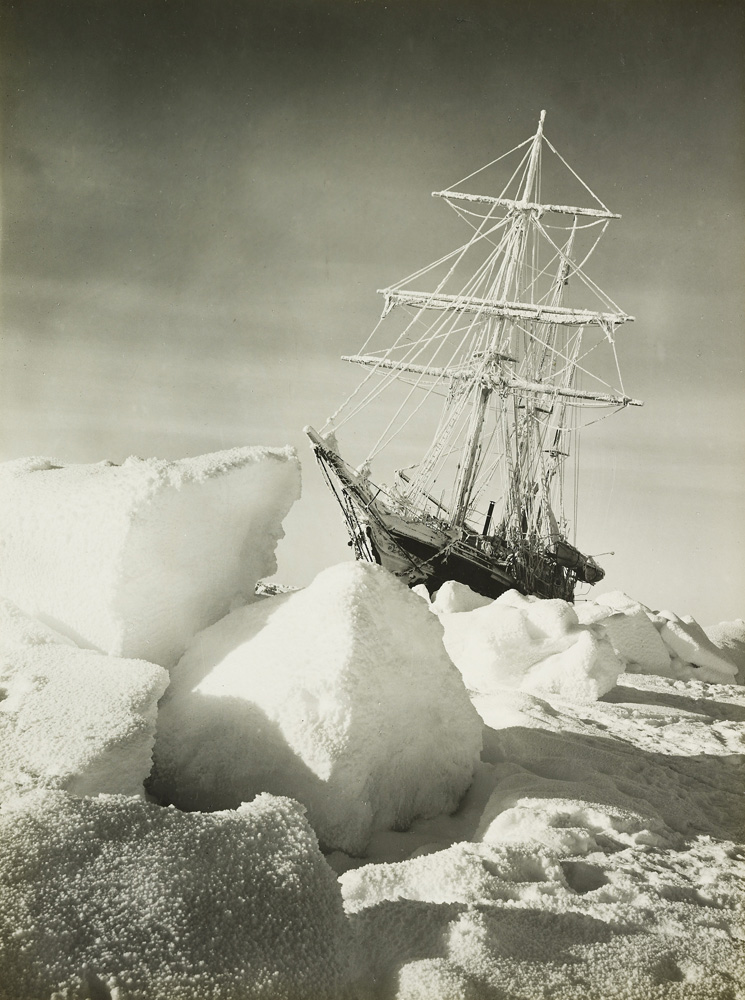

Ernest Shackleton’s grandiosely named Imperial Trans-Antarctica Expedition was remembered for the lives saved, not lost. Accompanied by the photographer Frank Hurley aboard the ship Endurance, Shackleton’s voyage hit the skids early in 1915, its main vessel unable to endure the deadly ice drifts of the Weddell Sea. The crew escaped on lifeboats to barren Elephant Island but Shackleton knew no rescue would come to them at the edge of Antarctica’s glacial waste. So, with four others, he set off in the James Caird — an open wooden boat with oars and a sail — across nearly 1,000 miles of terrifying sea, thick with ice and buffeted by storms, to whaling stations on the island of South Georgia. Improbably, Shackleton’s crew made it and within three months he returned to Elephant Island aboard a Chilean steamboat to rescue the remainder of his crew, including Hurley. Not one man who journeyed with Shackleton aboard the Endurance was lost. Not surprisingly, Hurley’s pictures capture scenes of comradeship — of men huddled together by a fire, of indomitable dogs perched in the snow. It’s friendship and trust — not simply the heroism of captain explorers — that can withstand life in the heart of the great alone.

Ishaan Tharoor is a writer-reporter for TIME and editor of Global Spin. You can find him on Twitter at ishaantharoor.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com