I arrived in the South Side of Chicago in June 2011 anticipating tall buildings clustered together and people relaxing on stoops, similar to my Brooklyn neighborhood. Instead, the large, century-old single family homes and sprawling lawns conjured visions of suburbia. Despite the frequency of blight, the wide tree-lined streets oozed tranquility. Yet within my first days in Chicago, segregation overwhelmed me. I quickly noticed that blacks and whites rarely mix, that the systematic neglect of black neighborhoods imprisons residents, and that an unexplained white woman strolling through neighborhood streets seemed to make people uncomfortable.

I’d come to Chicago after receiving a Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund grant to pursue a project about the city’s problems with food security and its urban agriculture movement. Around 384,000 people without transportation live more than a mile from a grocery store and have difficulty obtaining healthy options. But, because race weighs so heavily upon Chicago, I quickly became most interested the historical context of this modern day crisis. Time and again, I encountered mistrust and hostility on both sides: I swam through white entitlement on the north side, and black suspicion on the south. Still, people seemed relieved and eager to talk when I mentioned the ever-present segregation.

Chicago is one of those places where you can see recent U.S. history sprawled out before you, linear-timeline-style. From Industrialization to The Great Migration, to Redlining, to institutional segregation, to the refusal of banks to invest in black areas, to the departure of industry—the local economy, emotional empowerment, physical health and education have been stunted. Food security connects with the aforementioned issues, and is one way of examining the larger context.

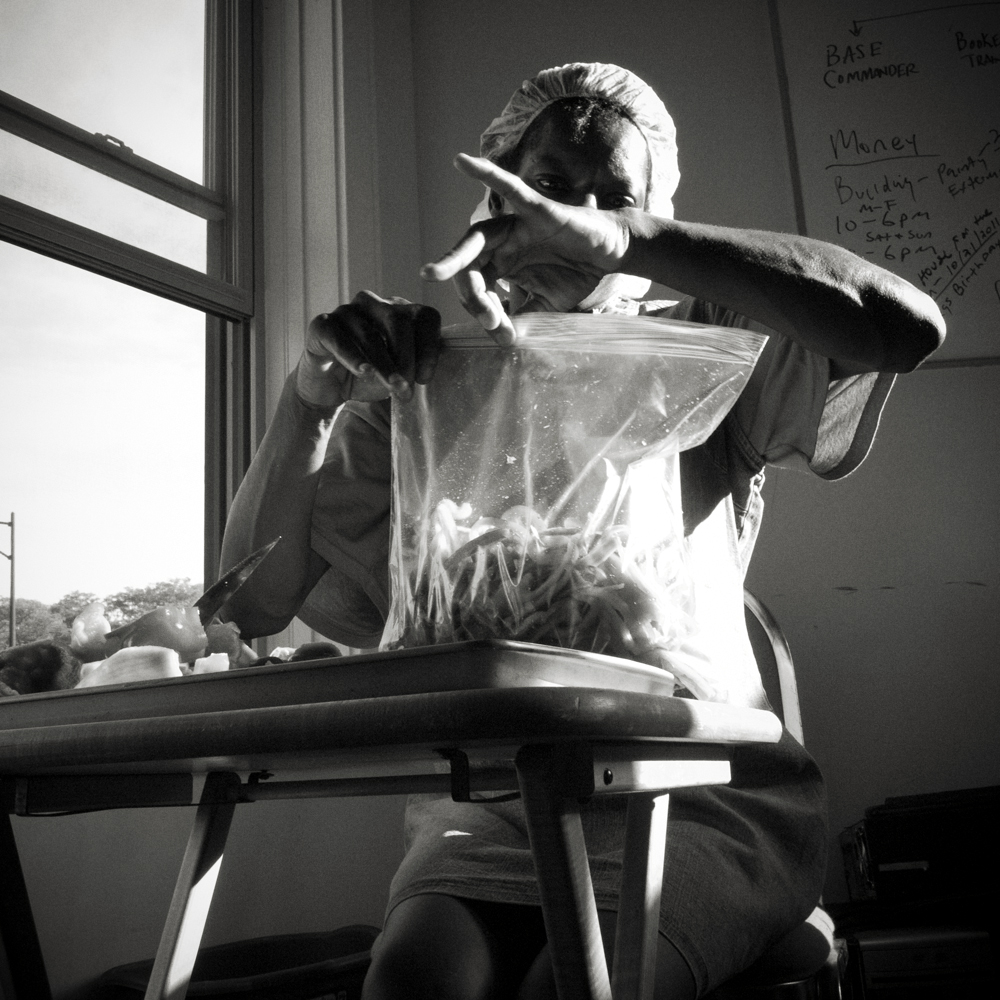

The more time I spent in Chicago, the clearer it became that the solution to food security requires more than just food. At grocery stores, I saw shopping carts overflowing with processed products, regardless of whether the store sold fruit and vegetables. Conversely, I visited community gardens and witnessed the profound power of gardening to inspire healthy living, reduce stress and connect those involved with a larger purpose. Yet the reality is that not everyone in the community is interested in gardening or buying healthy food. Further, Chicago’s brutal winters limit the outdoor growing season to roughly three months.

Halfway through my first month of shooting, I met Orrin Williams, the founder and director of the Center for Urban Transformation. Born and raised in the South Side community of Englewood, he is familiar with Chicago’s problems and invested in finding holistic solutions. After 30 some years advocating urban agriculture and sustainable communities, Mr. Williams is convinced that building chain grocery stores won’t fix the problems. Instead, Mr. Williams has devised a holistic community redevelopment plan. Williams seeks to convert abandoned buildings into locally owned businesses that will enable the community to thrive. These entities include: year round indoor gardens, health and exercise facilities, stress-reduction centers, healthy cooking schools, community centers, arts education centers, and, perhaps most innovative, a new model of small grocery stores that provide affordable healthy food and free onsite cooking instruction.

Willing to engage me in hours of thought-provoking conversation, introduce me to people and places who add depth and breath to my project and be seen with a white woman, Mr. Williams has been an essential partner in my work.

In the next phase of this project, Mr. Williams and I are working together to create a public art installation that invites Chicagoans to visualize what a sustainable community would look like. I want my photographs to do something tangible, and I want to recognize and unite others who have done substantive documentary work in Chicago. Inspired by the belief that a collective voice is stronger than that of one person, we are seeking other photographers to collaborate with. Our images will be printed onto weatherproof material and installed on blighted buildings. Alongside the images will be text asking viewers to envision the blighted structure as a community center, grocery store or cooking school/ Viewers will be invited to voice their support by signing a petition via text messaging. For more information please view our Kickstarter campaign.

Emily Schiffer is a Brooklyn-based photographer.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com