Colin Delfosse was in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) documenting conditions in copper mines when, returning to Kinshasa one evening, he saw a masked man perched atop a car, leading a procession of drummers and several dozen men and children.

Intrigued, the Belgian photographer began asking around and learned that what he had witnessed was the afternoon build-up to one of the city’s most popular sports: wrestling. In a country that, from 1998 to 2003, was the center of one of the bloodiest conflicts since World War II—8.4 million people killed from eight countries—one wouldn’t expect to find crowds clamoring to watch men pretend to beat each other up, Hulk Hogan-style. But influenced by broadcasts of American wrestling in the 1970s, the Congolese adapted the sport, bringing their own spin—parades, voo-doo and body paint. The sport is so firmly entrenched that even the president’s body guard is a popular wrestler, known as “Etats-Unis,” and one of Kinshasa’s district mayors even sponsored a match to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the country’s independence from Belgium.

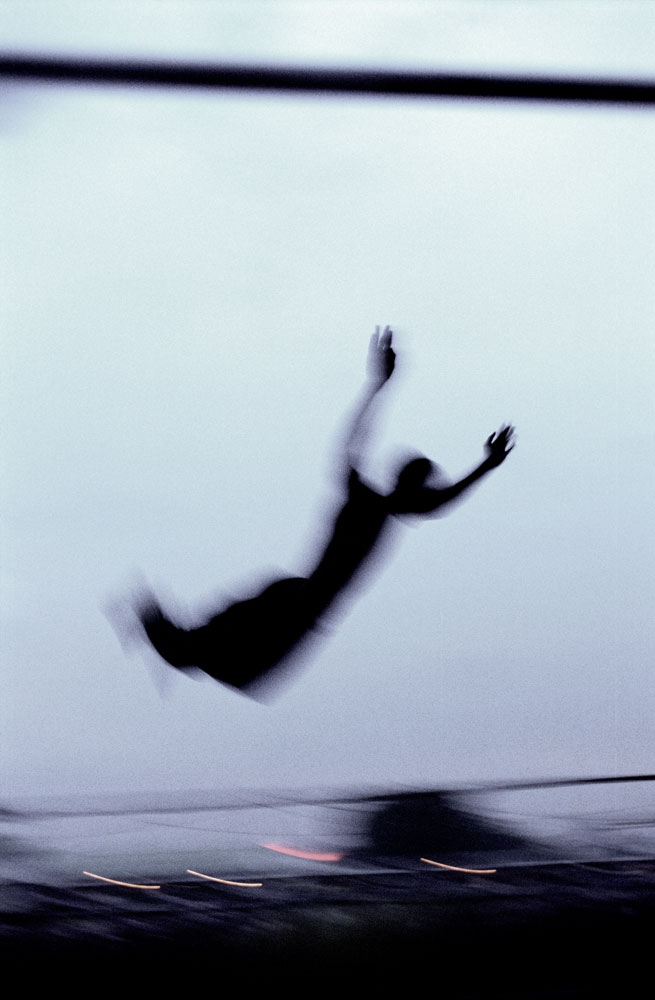

In the DRC, there are two branches of the sport. The first is the more recognizable WWE SmackDown-brand, villain vs. villain match, where wrestlers craft costumes out of spandex, wear masks and choreograph a physical tussle. The second, called fetish wrestling, involves opponents, wearing antelope horns or fake machetes through their skull, dancing, casting spells and using witchcraft to combat each other.

“The classic wrestlers consider themselves more important,” says Delfosse, of the group who have day jobs as taxi drivers or bouncers. “They train hard, lifting weights every day. The fetish wrestlers have more of a rock’n’ roll lifestyle—they sit around, drinking beer and smoking weed.”

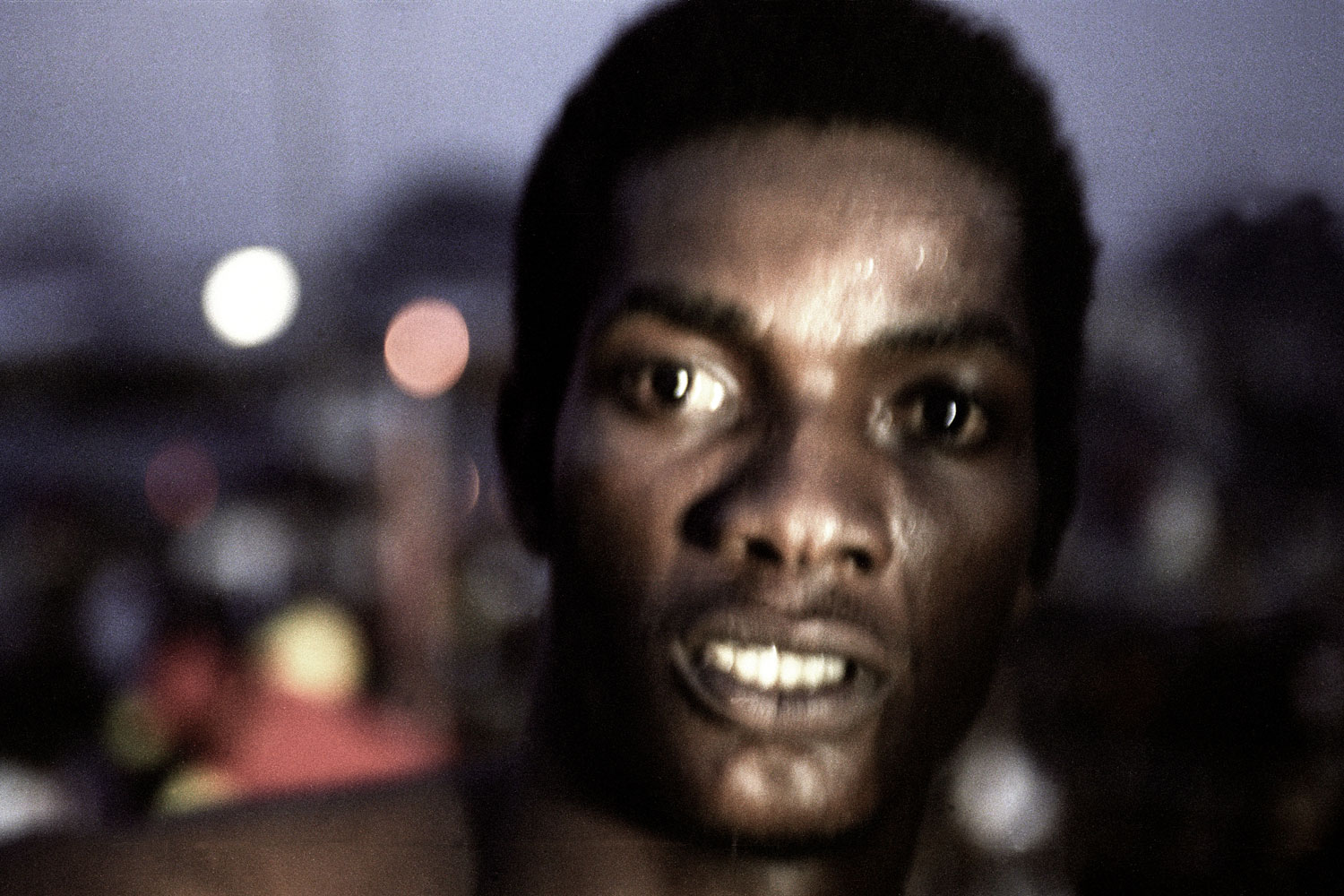

Gaining his subjects’ cooperation took a while; it was months before Delfosse was able to ride with wrestlers to and from the matches (protection he was relieved to get, as in the early days he was roughed up coming home from a match in a dangerous neighborhood and his cameras smashed). But even with that access, photography is viewed with suspicion, and getting portraits of the wrestlers often took a few hours of negotiation. “They always think you’re going to earn millions from the photo. They’re reluctant and they want to be paid. So you drink a beer with them, and tell them no, you’re not going to get rich,” said Delfosse. “Sometimes four hours later, I can take their picture. You have to be patient.”

Working inside the wrestling scene changed Delfosse’s feelings about Kinshasa. He admitted he hated the noisy, chaotic capital—considered one of the most dangerous in Africa, with a homicide rate almost six times greater than the continent as a whole—when he arrived. While the violence that still pervades the society is just below the surface of the matches—Human Rights Watch documented a mass rape, abduction and torture in a couple of eastern villages just last year—the sport showed Delfosse a different side of the Congolese. “They’re surviving day-to-day. There are no jobs, no infrastructure. When they wake up they don’t know what they’re going to eat for dinner that night,” he said. “It’s hard and tough, but this is a way to show they kept their sense of humor.”

Colin Delfosse is a documentary photographer and a founding member of Out of Focus photography collective. See more of his work here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com