It seems fitting that Massimo Berruti was holed up in the Swat Valley in Pakistan for three months early this year, right around the time when dozens of other photographers were off shooting the Arab Spring. The war in the Pashtun tribal territories long predates this year’s conflicts—and is likely to last far longer too. The result of Berruti’s long stay, the exhibition and book Lashkars, is a powerful body of work of conflict photography, yet it has a more lasting feel than much of the work that’s emerged from this year’s tumult. That sense of permanence was the point of the commission, the second Carmignac Gestion Photojournalism Award, in what’s become an annual competition. The foundation says it aims to support in-depth photojournalism at a time of “a several financing crisis.”

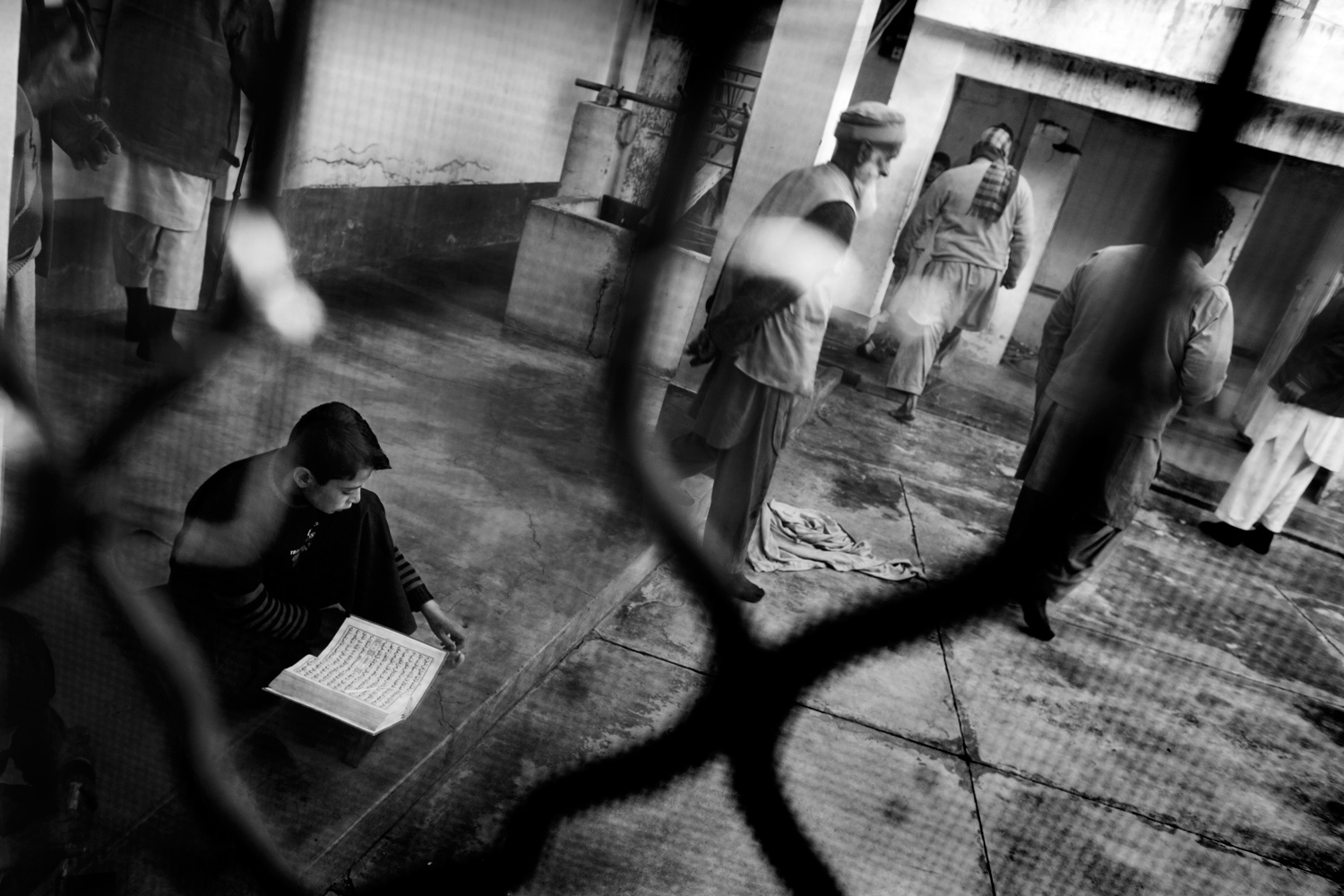

Berruti, an Italian photographer represented by VU, based in Paris and Rome, has little interest here in the war on terror, American drone attacks or even, for that matter, death. The Lashkars are Pashtun civilian militia, which have fought the Taliban for control of their valley for years, with tacit acknowledgement of the Pakistan Army, yet with little concrete support. And it’s their grinding, even humdrum daily existence along the amorphous frontier land which intrigues him.

The black-and-white images are quiet and emotionally ambiguous. In one, a young man stands in front of the rubble of his parents’ home, aiming a rifle at the sky. Is he shooting at some invisible drone miles above? We don’t know. In fact, Berruti says, he’s an 18-year-old Pakistan-born Londoner called Jalal Khan, who’s returned to his village to marry a childhood friend. The rubble isn’t from a drone attack, but from Taliban fighters who’ve destroyed the family house in retaliation for the Khans’ anti-Taliban views. In another image, a child carries a tree branch past the bombed-out ruins of a Taliban commander’s house. But it’s not just a photo depicting a boy collecting firewood. The children are claiming back their neighborhood, by stripping the trees around the commander’s house. “It was a sign of freedom and emancipation,” Berruti says.

The exhibition’s textured portrayal of the area extends to the spectacular valley and mountains, which you might have expected Berruti—who loves shooting panoramas—to photograph. Instead, Berruti’s used his artist’s eye to offer something far more timeless: A painted mural of the landscape, which is pasted across the wall of a gas station. There’s a jagged crack down the side of the wall, a sign that this tourist idyll once known as Pakistan’s Switzerland is a deeply disputed place.

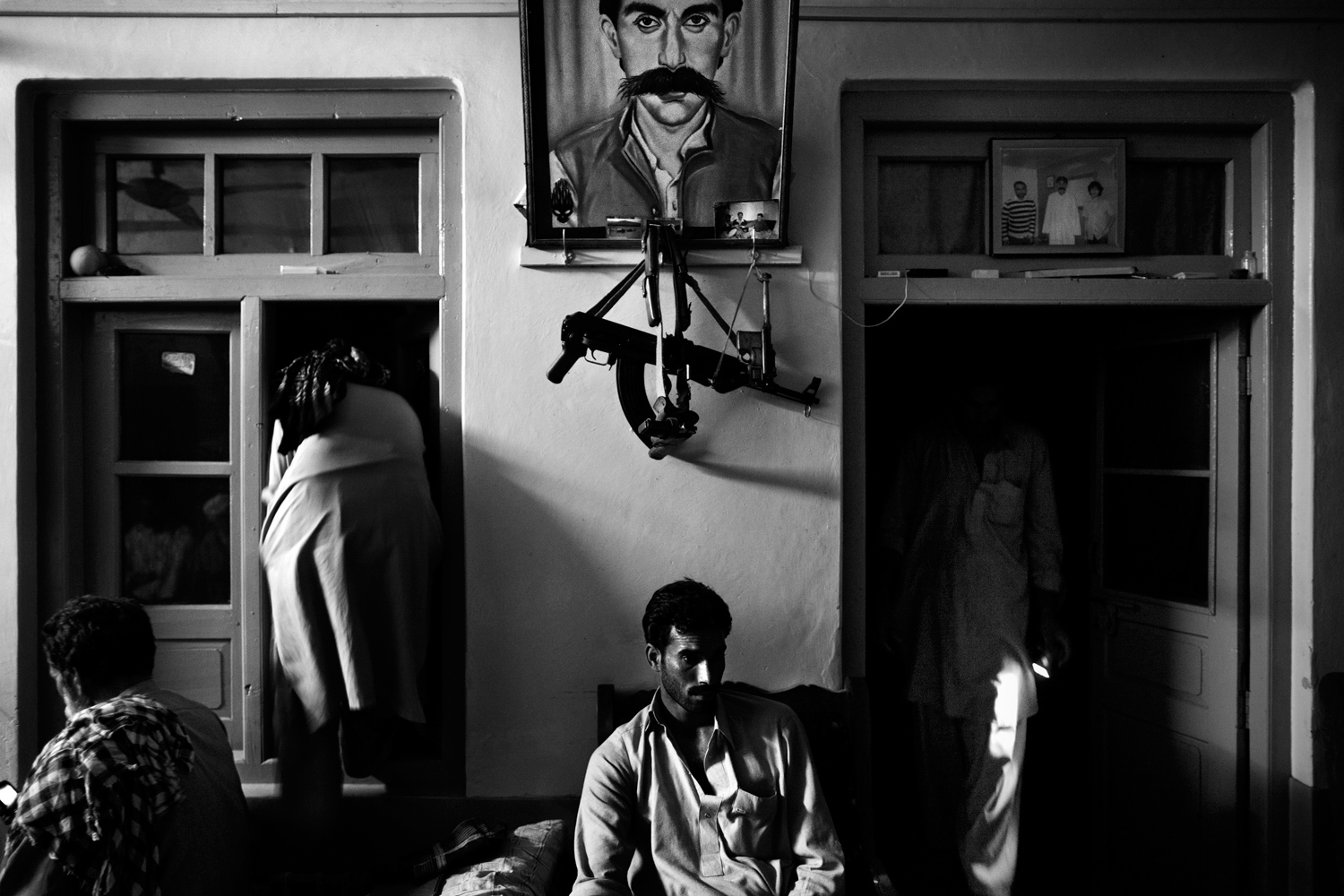

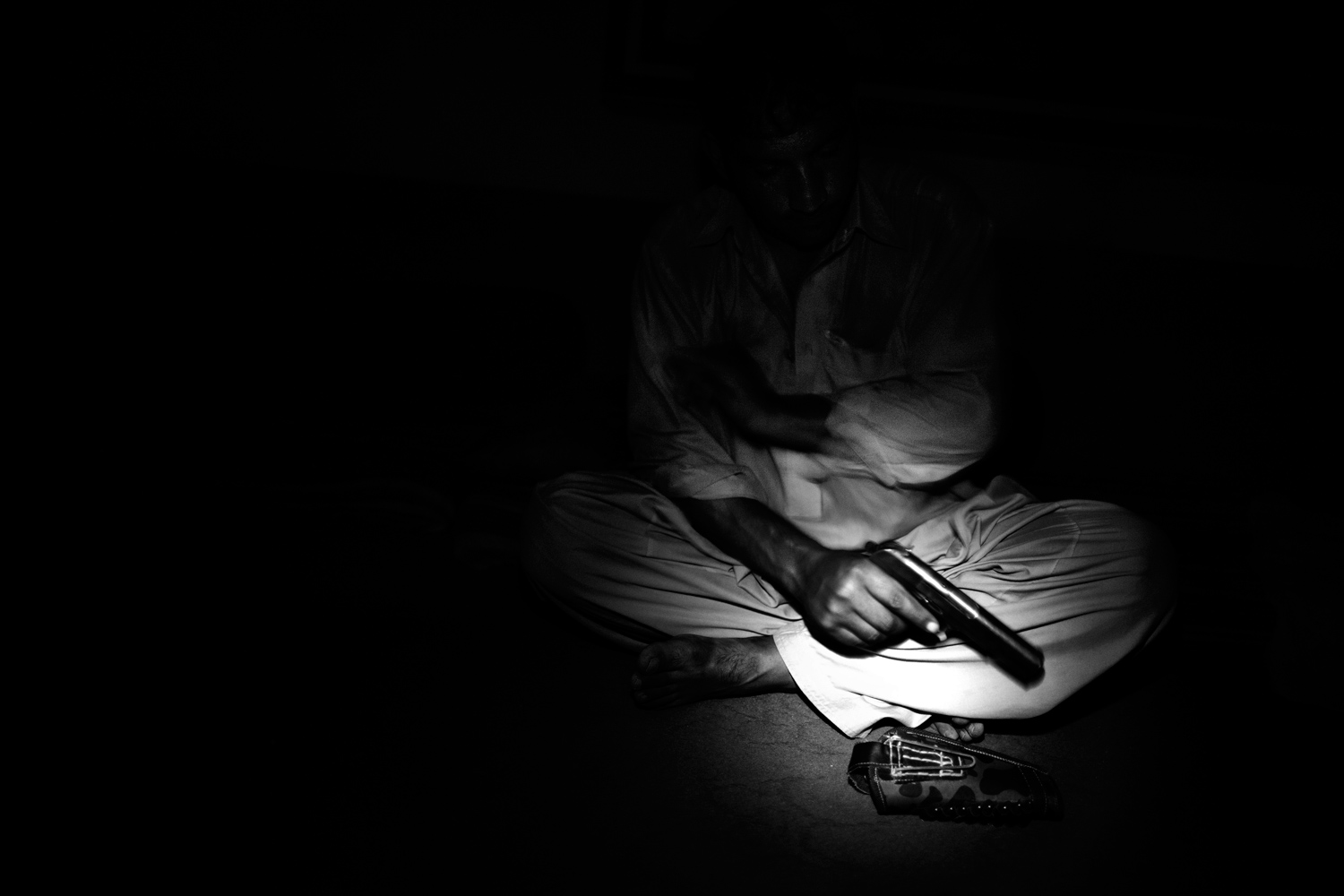

Despite the presence of guns and rifles everywhere, the conflict is off-stage. It’s so part of normal life that the business of fighting and killing hardly needs photographing. The story of war is instead etched into people’s faces, like the lined forehead of Saidbacha, the chief in Mahnbanr, who sits holding his pistol, gazing into the lens with what looks like a smirk. “He was the first to engage in battle against the Taliban before the Army arrived, and told me he’d killed four Taliban with his own hands,” Berruti says.

This was no easy world to penetrate, even for Berruti, who first traveled to the area in 2008. He kept secret his prize money—a whopping €50,000 ($68,000)—fearing that local chiefs might demand a cut in exchange for allowing him to work there. He also labored hard for permission to spend more than two weeks in the area, since Pakistan’s government suspected that any photographer opting to spend months there was surely up to no good. Berruti’s used his time well, depicting the long winter months when the Swat Valley is snowed in and isolated from the outside world. And the quiet moments appear to have been captured after weeks of Berruti winning the trust of locals and being able to melt into the background. As VU’s creator Christian Caujolle says in the forward to the book, there’s a feeling of “the photographer waiting.”

Given this intensely conservative area, it’s no surprise that women are completely absent from the exhibition—an unfortunate vacuum, given that Berruti focused so deeply on the Lashkars’ daily life. Berruti says he asked several times to photograph women, until he realized that “to continue to ask for this was putting me in a bad light.”

Finally, a disclaimer: I was a member of the jury for the first Carmignac award, which met in Paris in November, 2009. Led by William Klein, we sat around a conference table at the Ritz Hotel, poring over dozens of portfolios in search for a winner. After our discussion dragged on for hours, Edouard Carmignac—who heads the investment company and created the prize—finally walked over from his office on the Place Vendôme and suggested we continue over (what else?) a long lunch. He then listened intently to the discussion, enthralled at the excitement the prize had evoked. After hours of fine food and wine, Carmignac admitted to having his own favorite for winner, but insisted that the process was a “democracy,” in which he had no say. His prize is aimed at picking one photographer each year to spend months in an area which Carmignac believes is under-covered; the first year focused on Gaza, and the third commission is Zimbabwe. Despite the big prize, Carmignac is strangely not flooded with submissions; there are 76 submissions for the prize Berruti won, and fewer than that this year. In the introduction to Berruti’s book, Carmignac writes that photojournalism needs “lucidity and courage, a hardened character, and nerves of steel.” And sometimes, it needs backers like Carmignac.

Massimo Berruti is a photographer based in Paris and Rome. Lashkars is on vew at the Chapelle des Beaux-arts in Paris until December 3, 2011. See more of his work here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com