For too long, African art has been viewed in the West through a distorted lens. The modernists of the early 20th century saw in its shapes a kind of atavistic ideal — divorced from the realism of European traditions — which became in part the basis for the budding genre of abstract art. But a new exhibit at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, accompanied by the photographs above, seeks to overturn that narrative.

Heroic Africans: Legendary Leaders, Iconic Sculptures is a landmark collection of sculptures, masks and portraiture from a range of historic moments and cultural centers in Africa, all presented with meticulous historical detail. Context is important, says the exhibit’s curator, Alisa LaGamma. “African art always gets presented as a type. These people have this kind of mask, or people from this region produce those kinds of figures. It’s so generic and I was very uncomfortable with that.”

Instead, LaGamma’s exhibit shows how many of the works on display, if considered in a particular context, could conform to traditions elsewhere. Why should we see this graceful sculpture below of the Queen mother of the King of Benin in a different light than, say, a bust of a Roman emperor or latterday European potentate, styled with mythic flourishes and a hopelessly perfect nose? Throughout the exhibit, there’s an awareness of the imperatives that produced much of these sculptures and objects through the centuries: namely, the impulse of local societies and those who led them to create totems of their power.

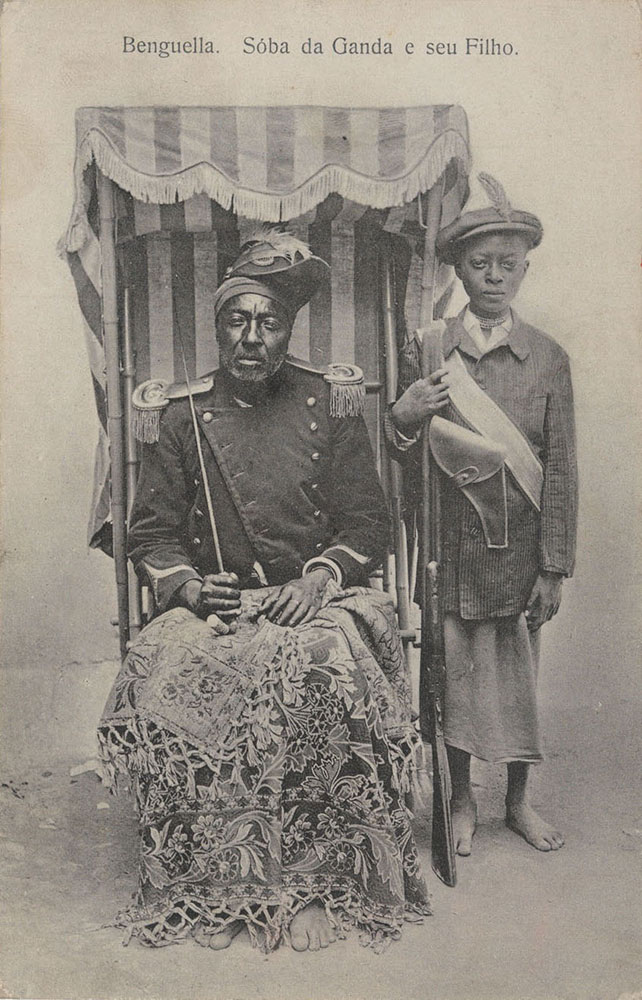

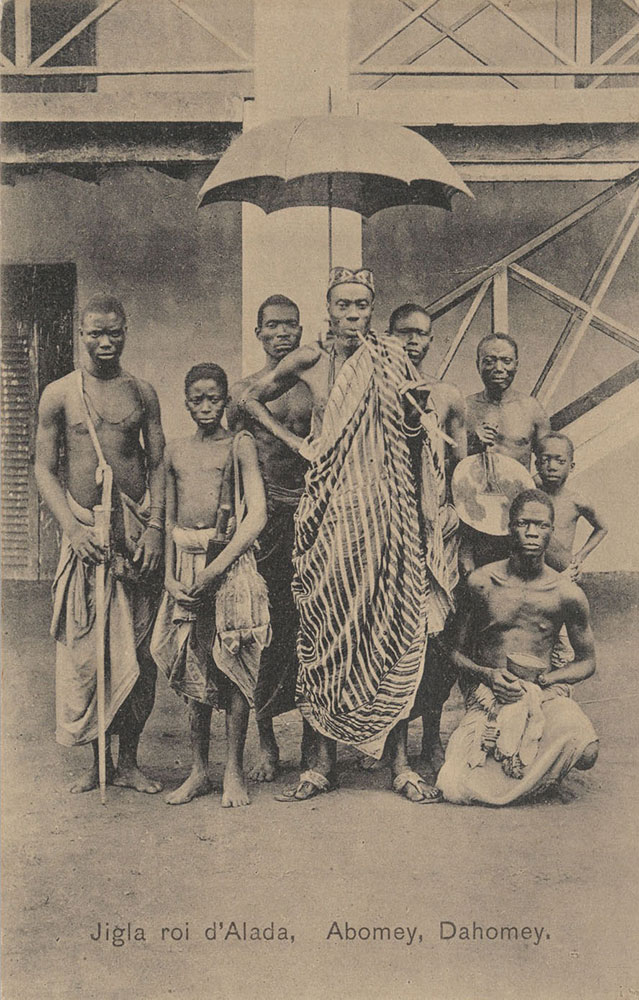

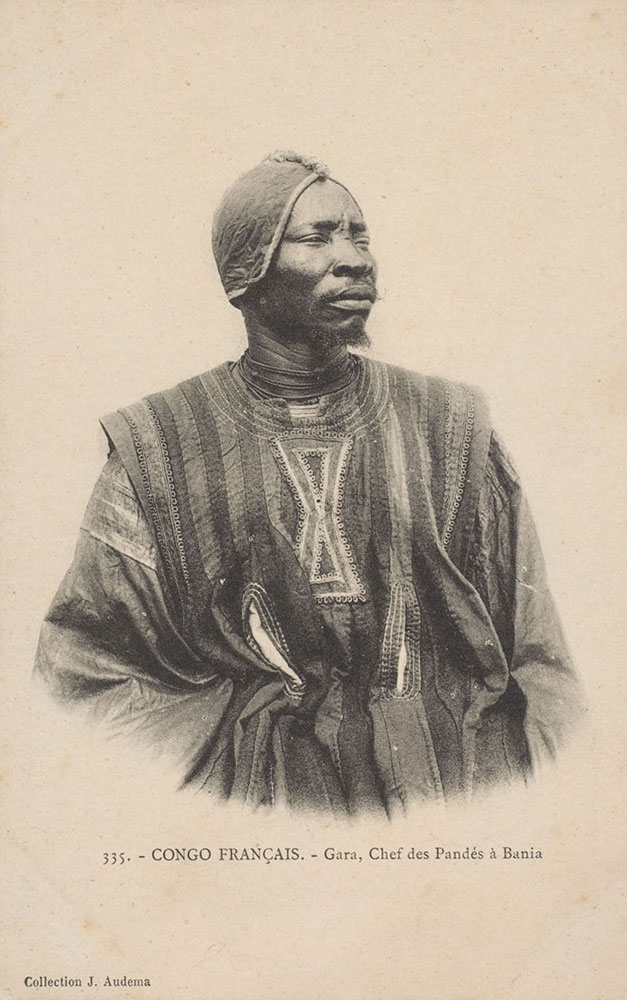

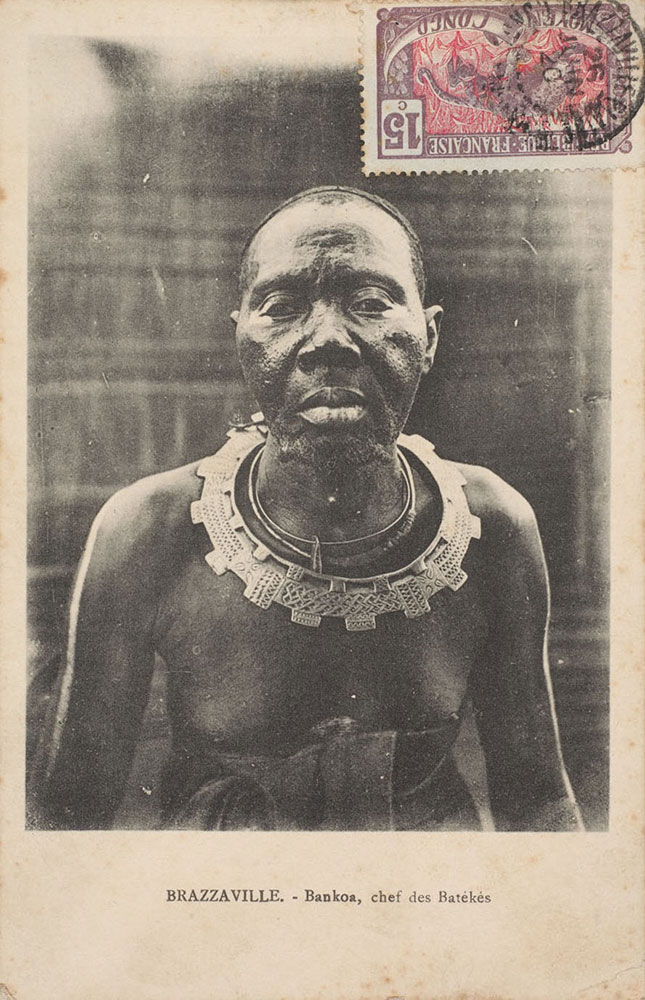

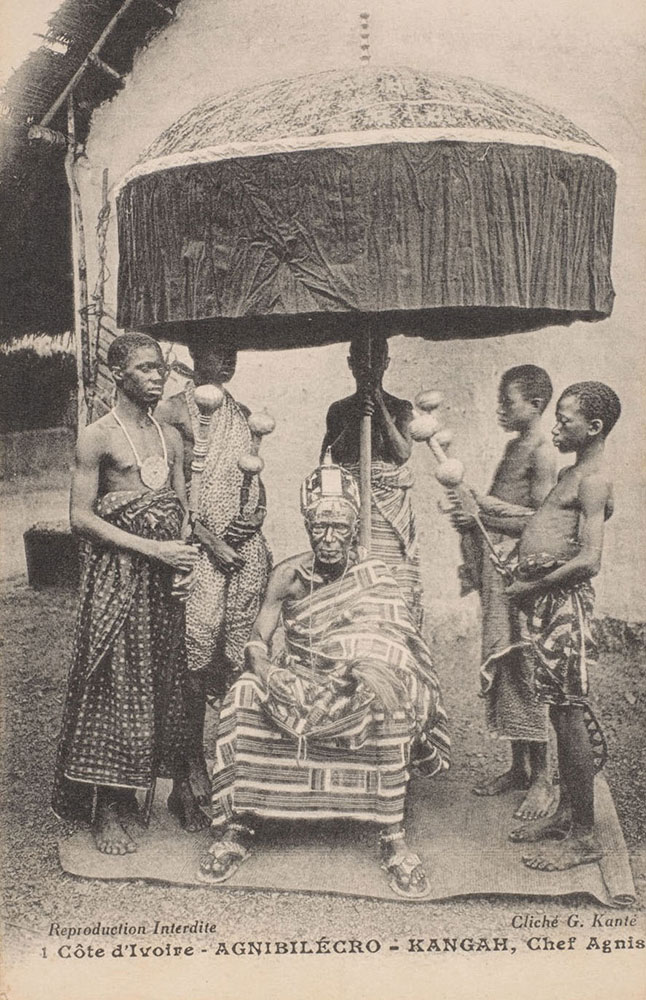

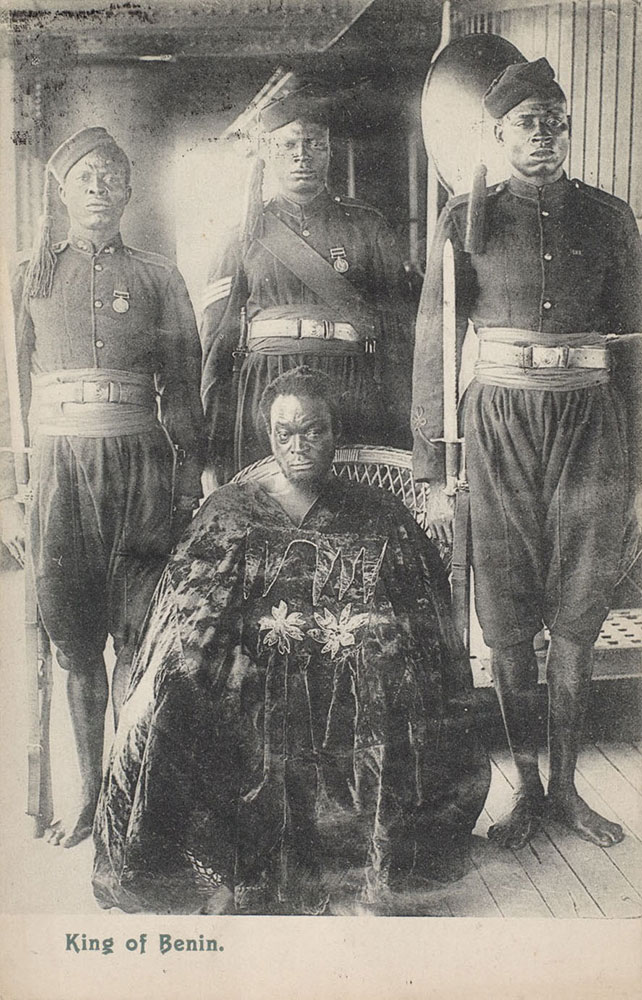

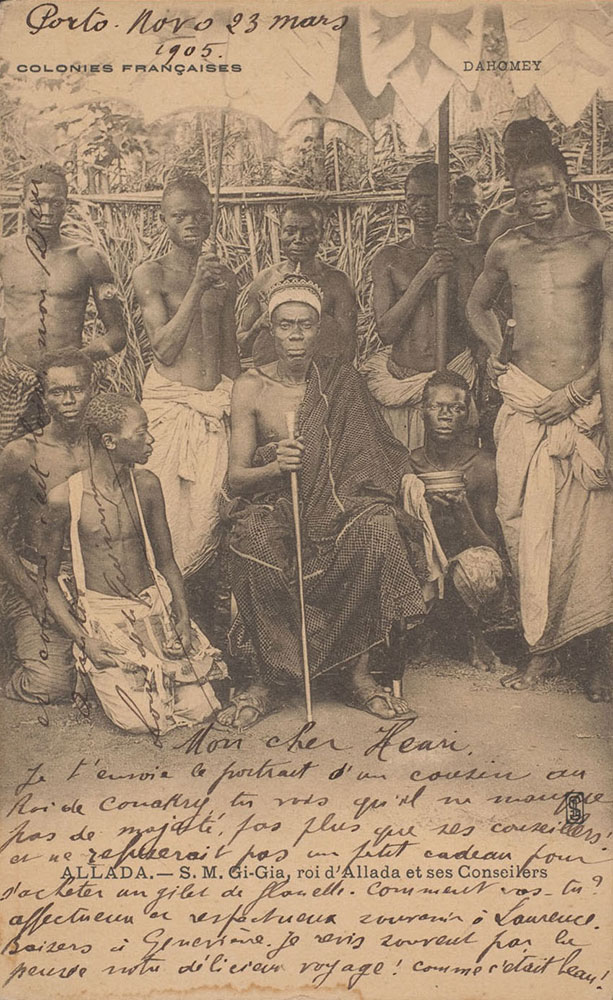

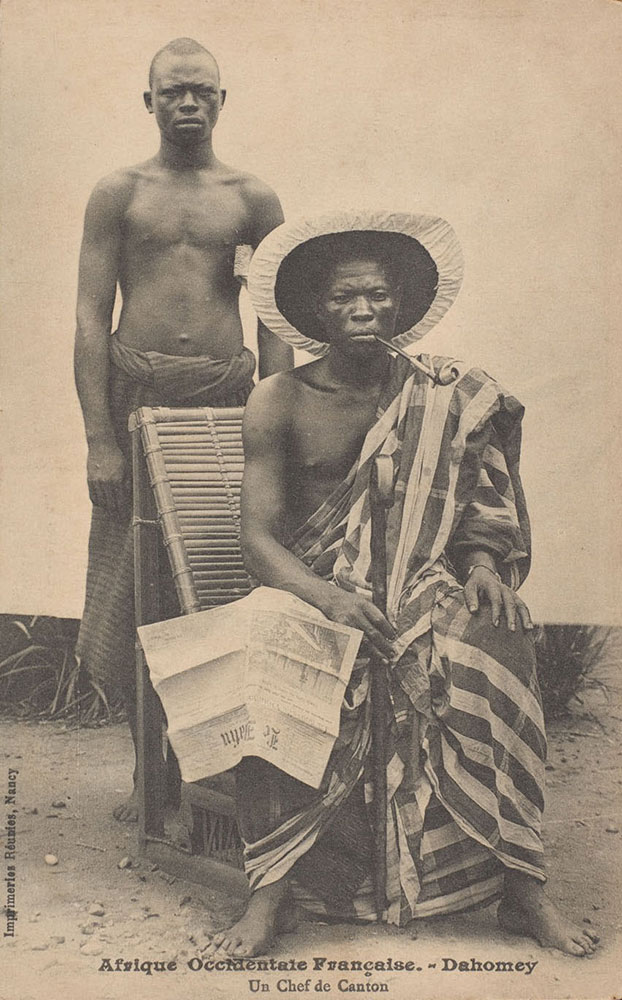

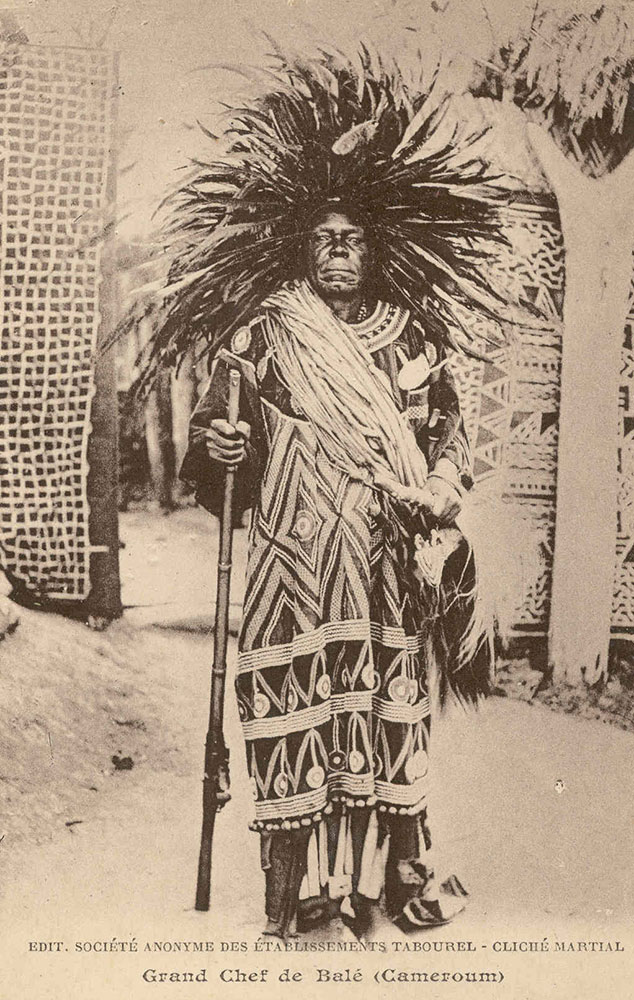

On the sidelines of Heroic Africans is a series of photographs of various African chieftains, tribal elders and kings taken in the late 19th century and early 20th century. These were produced by studios and ateliers that sprung up in parts of Africa; the pictures were disseminated as postcards and collectibles across the continent and to the rest of the world. The photos “are being taken at a very special moment in history,” says LaGamma. “A lot of the artistic traditions that make up the body of the exhibit wind up becoming anachronisms.”

After all, the introduction of photography came alongside the advent of direct European colonial rule through much of Africa. There was a craze to catalog and document the continent’s alien, subject peoples. There was also, in particular, an obsession with African nobility. In Ornamentalism, a history of the British empire, the social historian David Cannadine discusses how European imperial powers cemented itself by reinforcing and co-opting local hierarchies: “ceremony, monarchy and majesty… were the means by which this vast world was brought together, interconnected, unified and sacralized.”

As we can see, a lot of local African potentates were happy to pose for the foreigner’s lens. The postcards still show leaders in all their pomp and majesty, but they inevitably bear the weight of Africa’s subjugation by foreign powers. At the same time, more traditional objects and sculptures that defined whole communities and spoke of their ancestors were being whisked away to museums and private collections in Europe. Amassed as nameless artifacts in dusty imperial showrooms, they lost their local resonance. “There’s a disconnect that happened then,” says LaGamma, “between the image of power and the reality of that power.” That connection may not be ever fully restored, but LaGamma’s efforts are heroic in their own right.

Heroic Africans: Legendary Leaders, Iconic Sculptures is on display at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City until January 29.

Ishaan Tharoor is a writer-reporter for TIME and editor of Global Spin. Find him on Twitter at @ishaantharoor.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com