Libya didn’t simply fall at the end; it rather slid from the hands that had gripped onto it for far too long. It was taken back and returned to its rightful owners.

In the six months before my second return to Libya this September, after the fall of Tripoli, I had seen the way things would finally end through a romantic kaleidoscope. I wanted to celebrate in the square after finding my family in the crowd. I wanted to be my father’s son. I wanted that gap I have felt from Libya my entire life to at once close. With this uprooting of the regime in Libya, I felt whatever huge hole was left was now filled with a complex melody of emotions. I had not expected anything short of jubilation, and never had the impulse of reflection been a part of this plan for me. Before I had a chance to acknowledge the transition, it was already complete and it gave way to an incredible sense of pride. The rebels had brought the regime to the ledge, but it was the people who would be the final push.

At the time, the city celebrated but the country seemed exhausted. I had been afraid of the capital spiraling into chaos following the fall, but instead everything seemed to have taken its place. People went to work and took up positions to help attend to the city’s wounds—as if all Libyans had been rehearsing for this moment their entire lives. People grasped their roles at this moment and took hold of the importance of civility. During a visit to a hospital one day, a man explained to me simply, “We all have our jobs now. As a Libyan, you have your job here, and it is important. You do your job and I’ll do mine.”

I felt as though I needed that clear point of departure to help finally tether together these loose ends I had felt my entire life. In the end, all those emotions I had reserved for that anticipated moment were nowhere to be found. A kind of paralysis took hold instead. The previous expectations would pale in comparison to how this unexpected state would leave me. Joy was replaced with anger and clarity with haze. What became clear was that this hadn’t been my war as much as it had been for the rest of Libya.

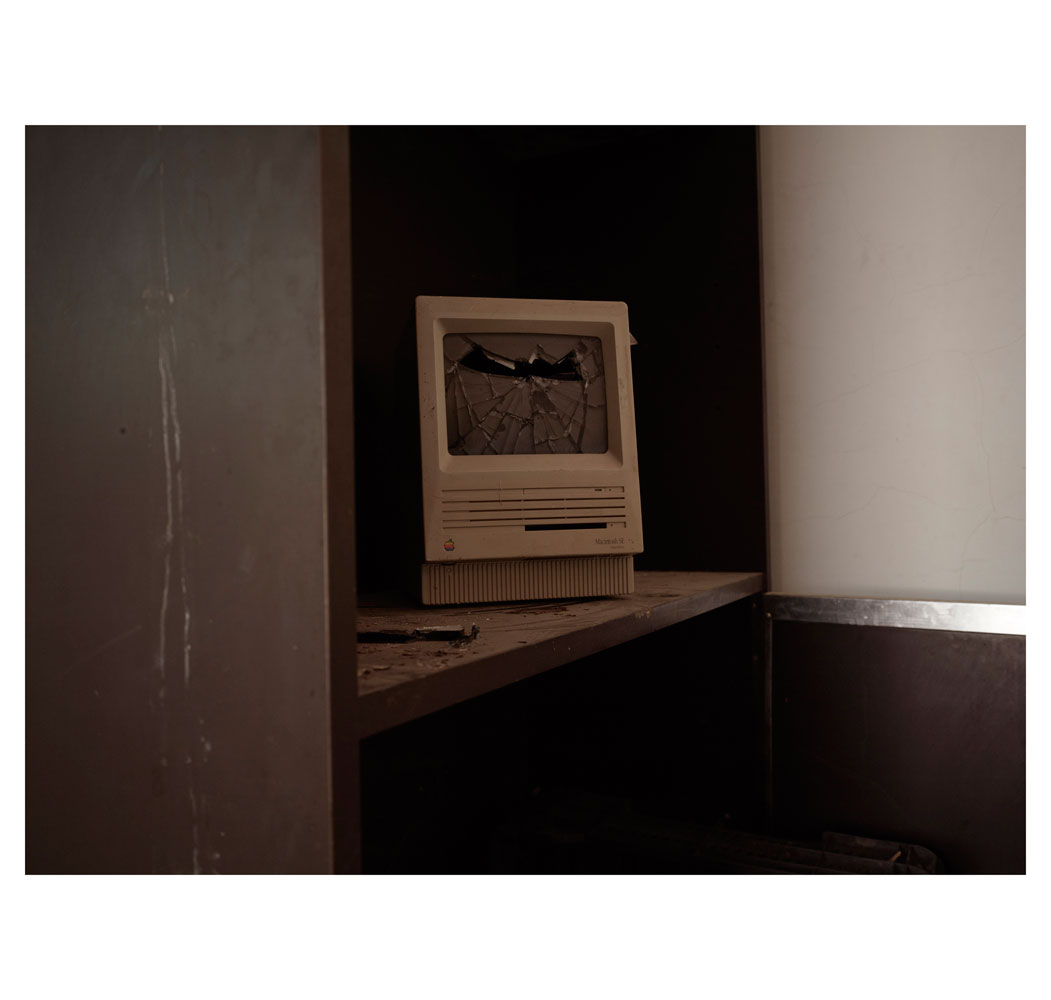

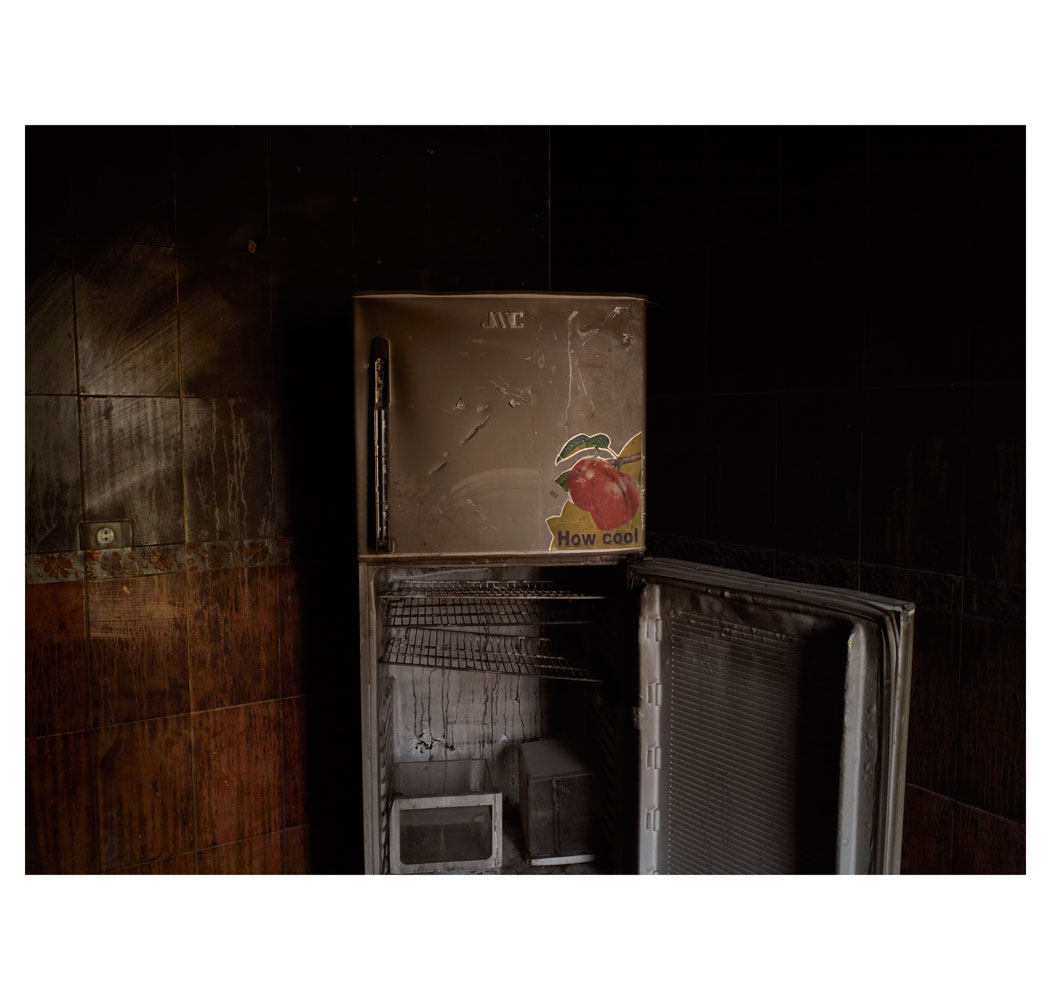

To me, the regime was like an ominous vapor. While their fighters were not visible on the streets any longer, evidence of their lethal effect was very present, and as they fled, they left in their tracks a deep gash in the country and its people.

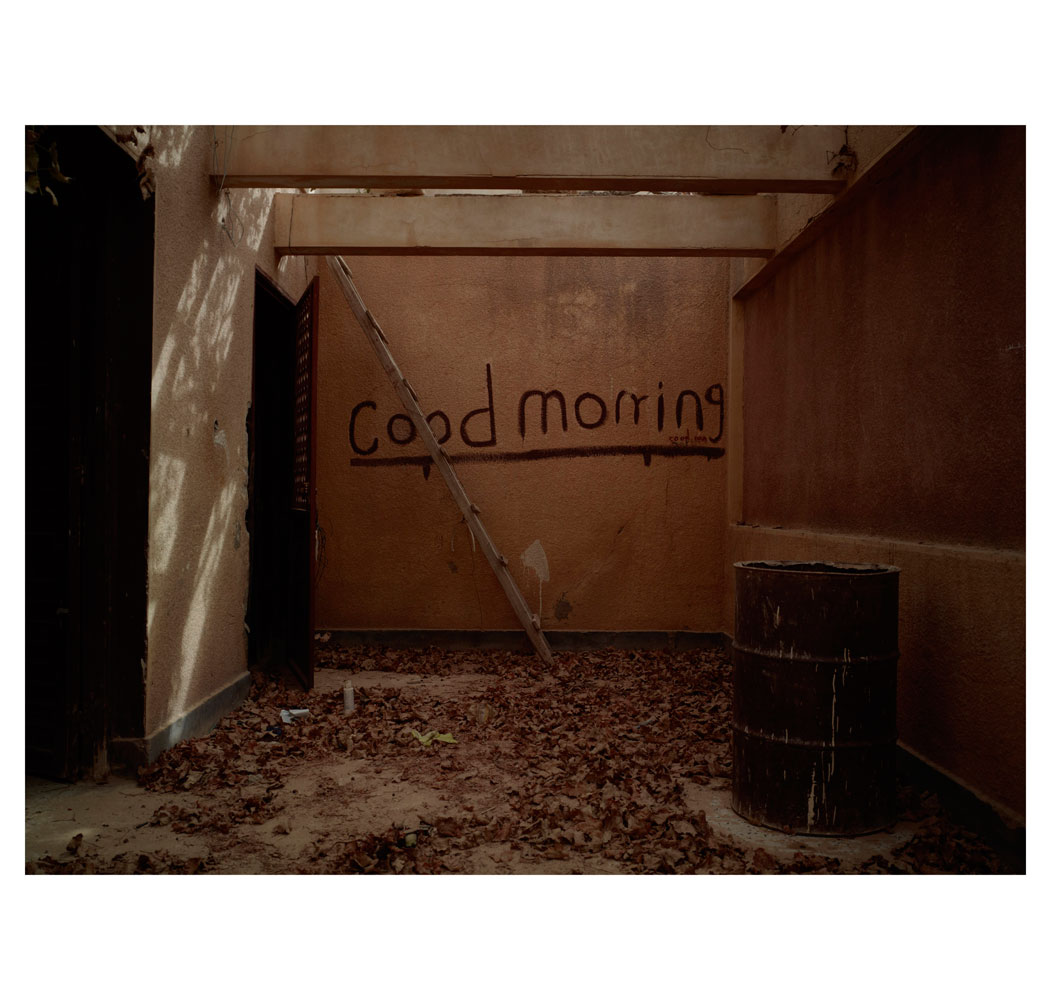

The personal conflict I felt during this time brought me to a point where my relation to breaking news played less an immediate role in my work than trying to restore my connection during a period when so much was unclear and surreal. Memories near and far rushed forward and I felt I needed to step back before the whole thing engulfed me. I had a clear reason for being there. More than one, in fact, and I wanted to get a hold of whatever I was experiencing and work towards a clearer picture. That image only became focused once I paused and allowed that nostalgia to catch up with me. It was an unconscious choice to proceed forward only when something made sense to me and I felt it somehow fit into this puzzle I was building. I realized that a middle distance was missing. The gap between me and what I was here to see was gone and I felt pushed up against this giant shift. I was able to see everything clearly. I needed that minor space to objectify this moment just enough to try and grasp it but I was immediately enveloped instead. As if all the oxygen in that needed breathing room was extinguished and a vacuum pulled everything from inside of me.

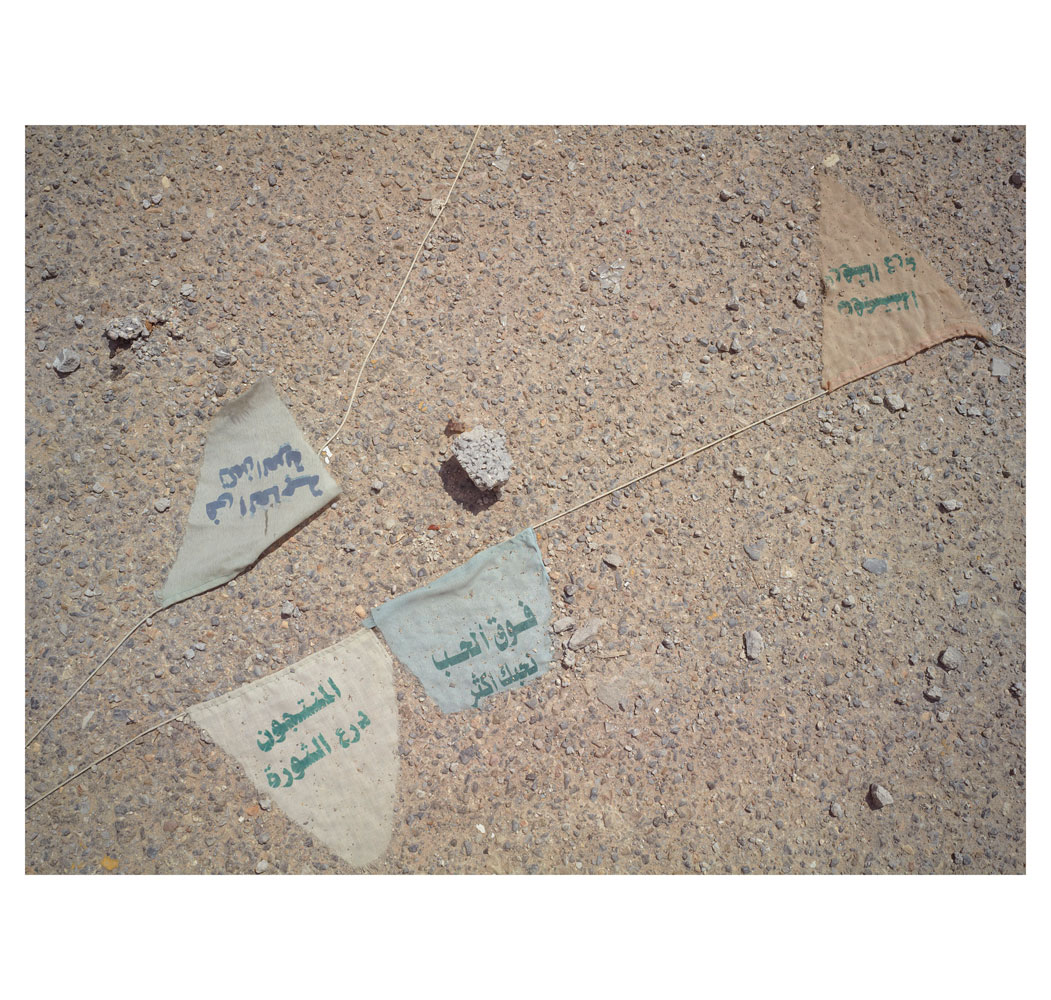

Much of what I became transfixed with might otherwise have seemed banal to some though it had a relevant place in processing this event. Whether it was the discarded green flags of the regime being slowly devoured by the elements, or the simplest gesture that suggested a great relief within this new absence in the country.

While the experience of this past return lent little to fully realizing how I had expected things to play out, everything in fact eventually did play out. The insignificance of those dreams had never been so clear once seeing and feeling the collective sigh of relief the country let out.

Jehad Nga is a Libyan photographer who lives in New York. See more of his work here.

To read Nga’s piece about his father’s life in 1960’s Libya, before the Gaddafi regime, click here

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com