October marks the launch of Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A., 1945-1980, a region-wide collaboration celebrating the birth of the Los Angeles art scene. Lyra Kilston reports on the landscape photography made in this prolific era, the second in a three-part LightBox series about PST.

Joe Deal, reflecting on his landscape photographs of the early 1970s, wrote: “Why contribute, I reasoned, to the growing pile of photographs of an idealized American landscape while it was being chewed up before our eyes by advancing suburban development, interstate highways and shopping malls?” Deal’s sentiments were shared by a new school of Southern California-based photographers, including Lewis Baltz, Henry Wessel and Robert Adams, who felt that landscape photography was languishing in a dreamy, nostalgic style which ignored the reality of a changing world. They sought, as Deal put it, an “unromantic and unfiltered way of looking through the lens.”

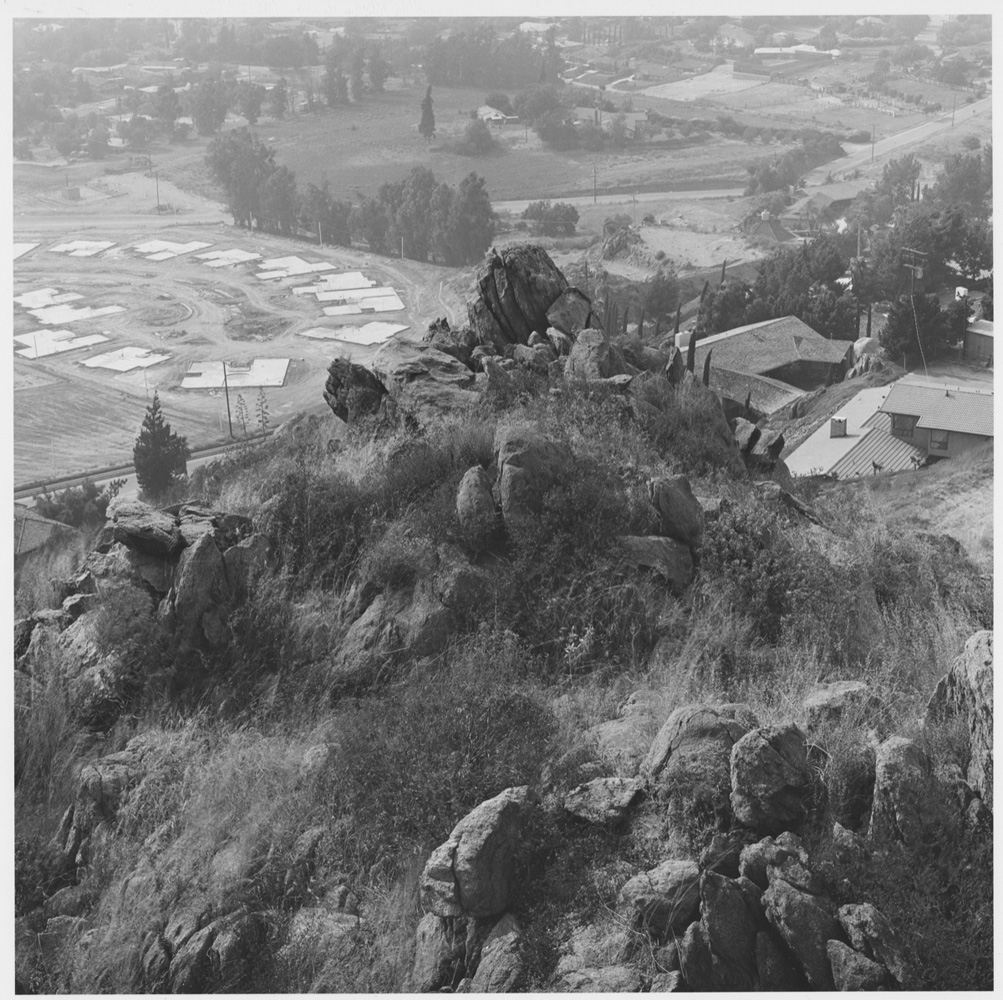

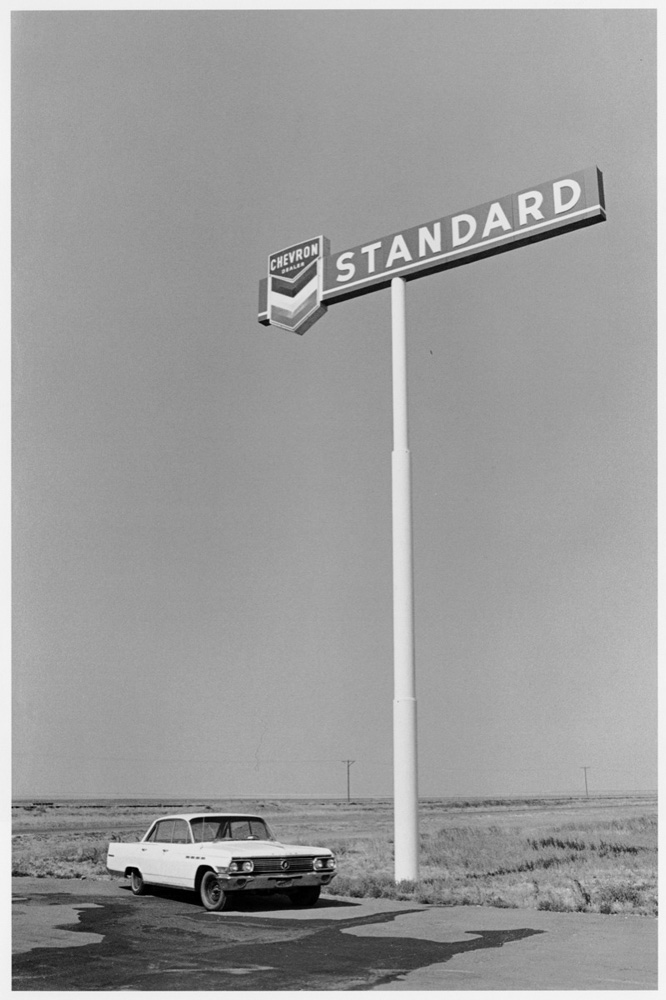

This different style of photography—now known as New Topographics after the title of a groundbreaking and highly influential 1975 exhibition at the International Museum of Photography in Rochester, N.Y.—departed from the legacy of idealized landscape photography mastered by Ansel Adams and Edward Weston by unflinchingly depicting the Western landscape as it had become: full of highways, housing developments and anonymous corporate buildings. The fascinating evolution from the sublime, high-contrast style of Adams and Weston to the cool, detached documentary look favored in the 1970s and 1980s is explored in the exhibit Seismic Shift: Lewis Baltz, Joe Deal and California Landscape Photography, 1944-1984, which features work by more than 40 photographers, now on view at the California Museum of Photography at the University of California, Riverside (where Deal and Baltz both taught).

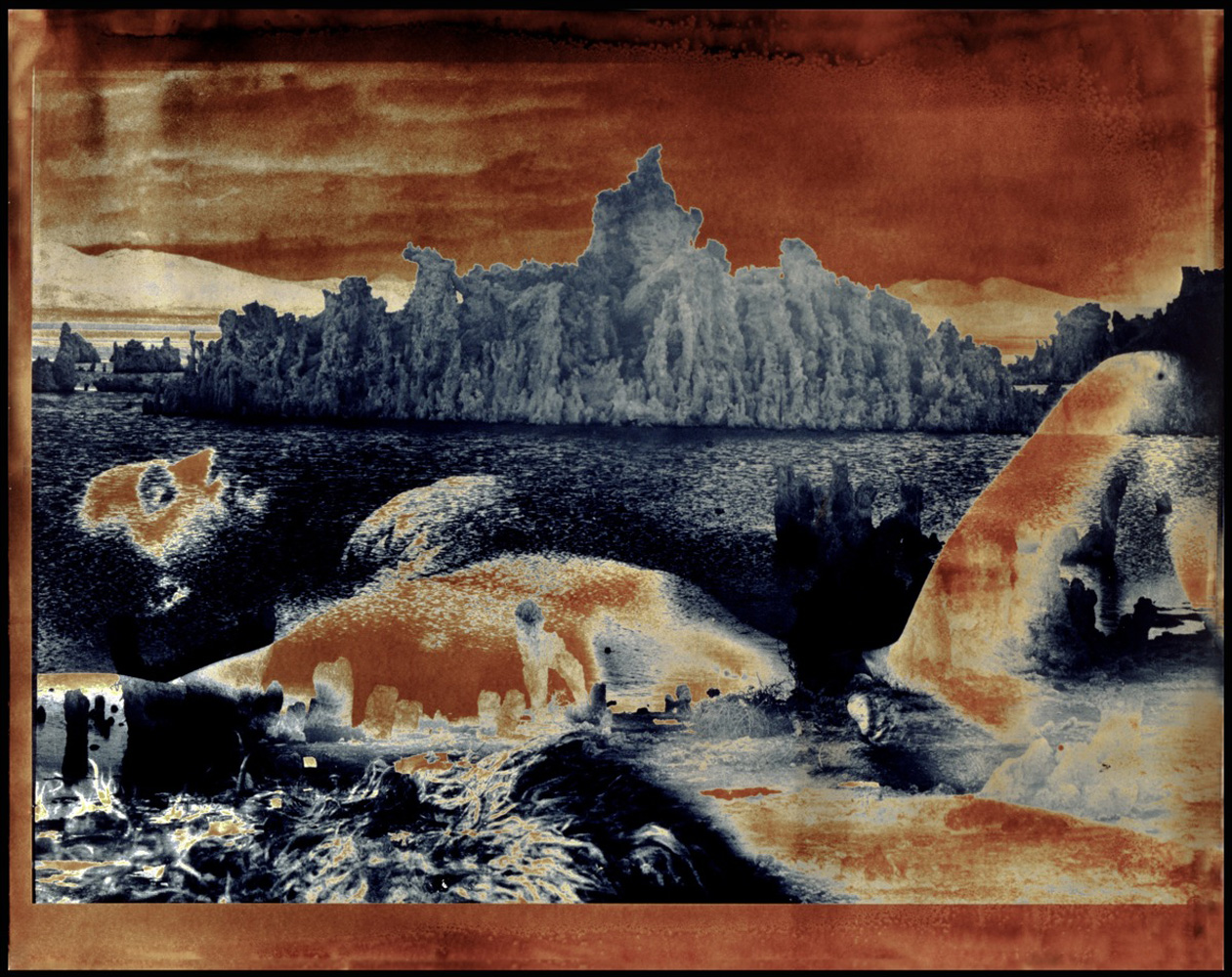

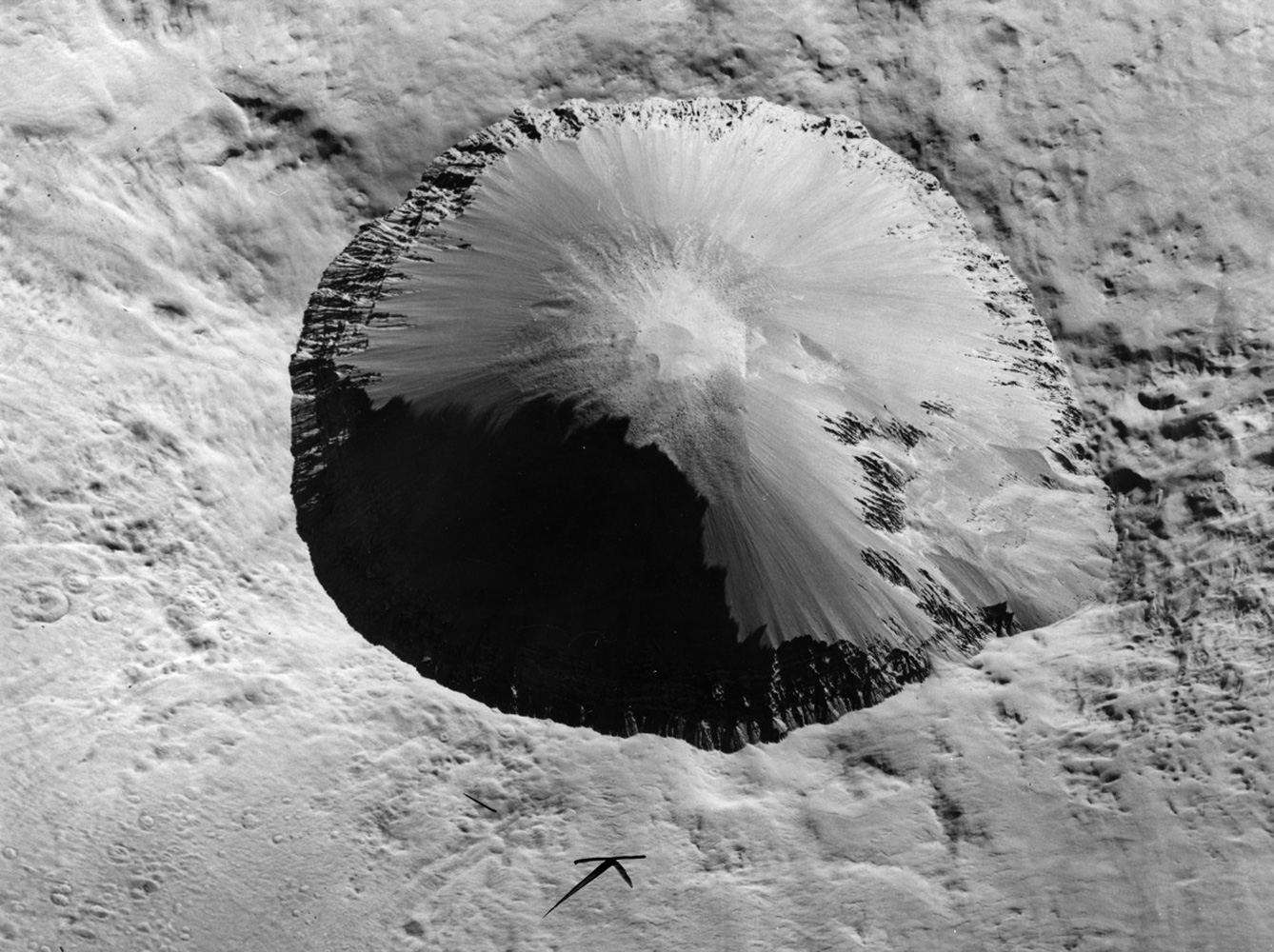

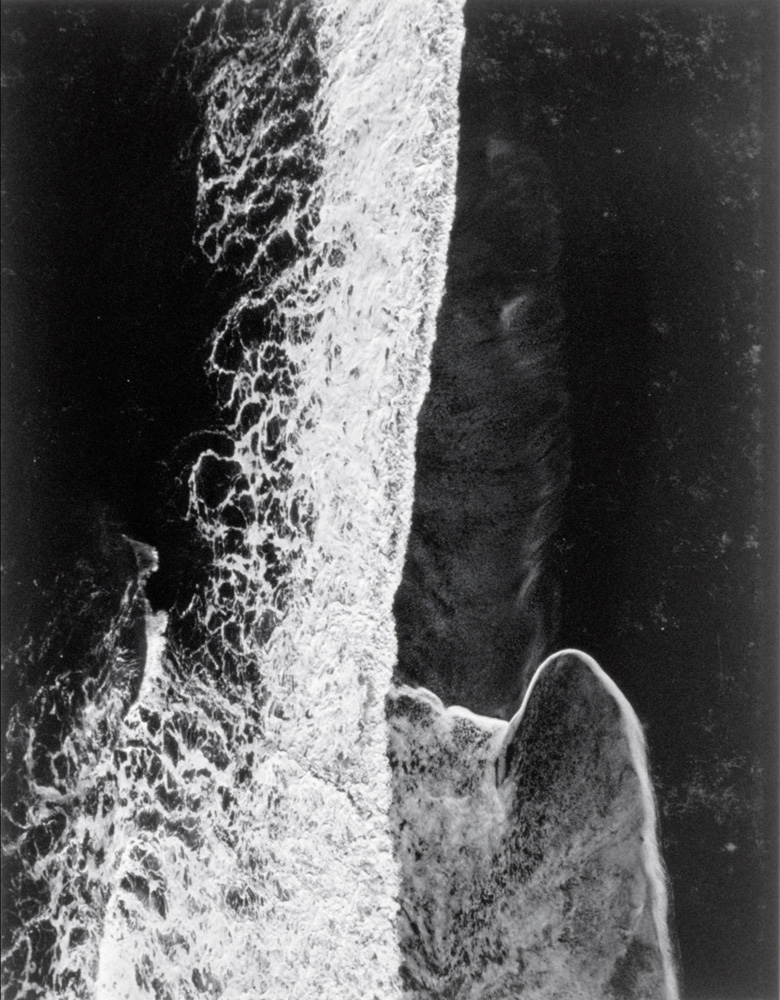

The early photographs in this exhibit showcase the majesty of unspoiled natural settings, but by the 1950s the influence of abstract art was apparent in formal compositions by Minor White and William Garnett. By the late 1960s many landscape photographers were heavily manipulating their images to convey psychological states and mystic symbolism. As one critic deemed it, this method eventually reached a point of “poetic exhaustion.”

In response, the New Topographic photographers portrayed the intersection of nature and civilization with a flat sobriety. Common subjects included abandoned storefronts, storage facilities and chain link fences, as well as examples of artificial nature, such as a mural of a farm painted on the side of a truck. In Wessel’s deadpan California (1969) a Chevron oil sign hovers over a blank desert of scrub brush, and in Los Angeles (1970), an electrical pole bisects an empty parking lot. Judy Fiskin, Laurie Brown and Leland Rice focused on the impact of tract housing and construction sites, while Grant Rusk shot hills sliced with paths of asphalt and concrete.

A sense of loss is inevitable when all that’s left of nature is a strip of dirt fringing a concrete wall, as portrayed in one of Baltz’s well-known images. Yet as Robert Adams noted, “Unspoiled places sadden us because, in a sense, they are no longer true.” As stark or banal as the New Topographic style was, there is a value and beauty in its truthfulness. Landscape had changed dramatically in the developed West, and photography had to change with it.

Seismic Shift: Lewis Baltz, Joe Deal and California Landscape Photography, 1944-1984, is on view through Dec. 31 at the California Museum of Photography at the University of California, Riverside.

Lyra Kilston is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in numerous publications, including Artforum, Art in America and Photo District News.

Read the first part of the PST series here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com