I met Harry Callahan in 1973 as an intern at LIGHT gallery in New York. It was a time when no one paid too much attention to photography. However, LIGHT was this great gallery, and the photographers all loved being a part of it. They’d make their pictures, print them and bring them in to the gallery. LIGHT held first-rate exhibitions every other year for the artists, and it was something they were terribly excited about. Prior to that, the only hope a photographer had of having an exhibition was to show at a major museum, and the only one really doing that on a consistent basis was The Museum of Modern Art.

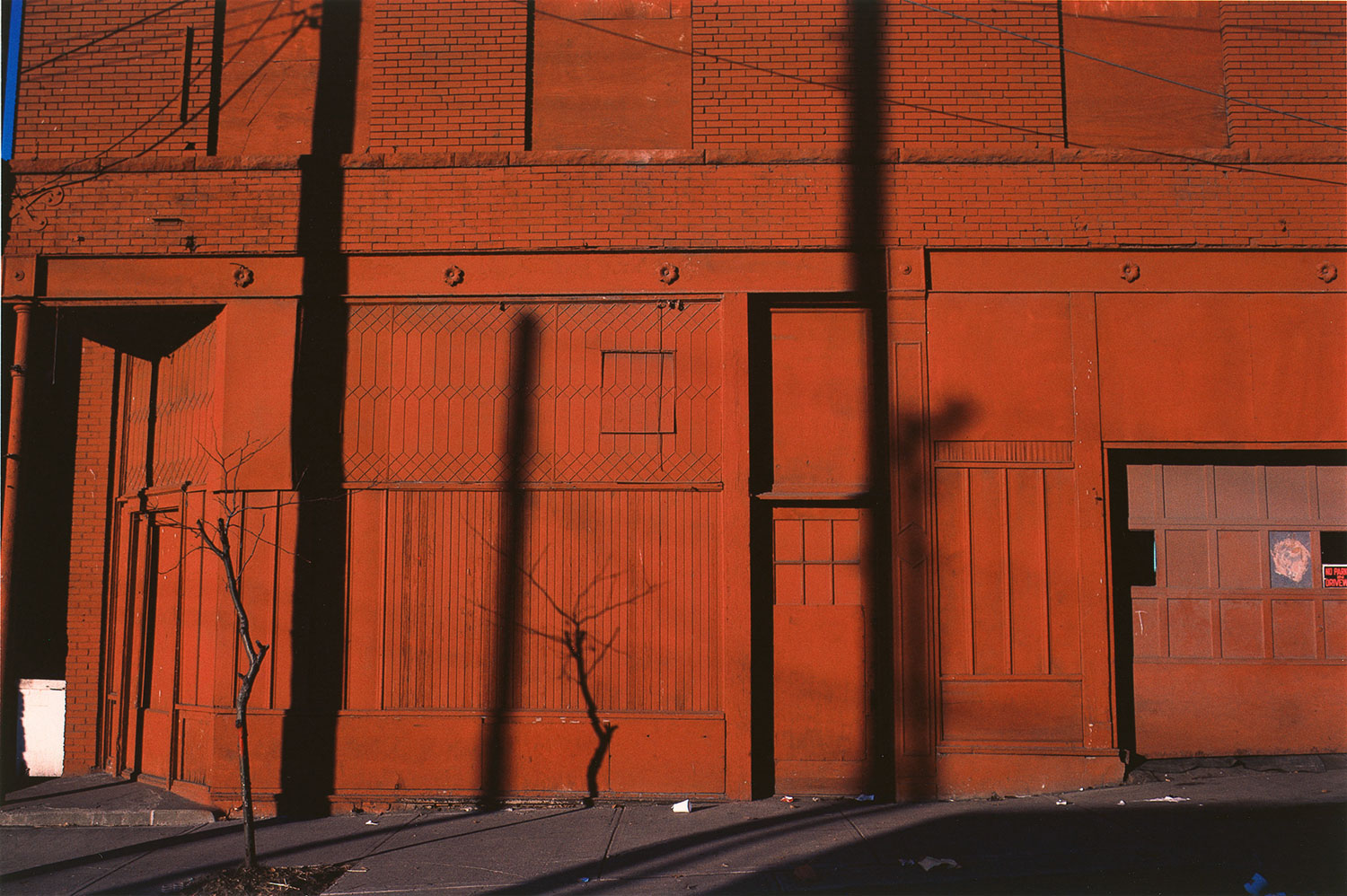

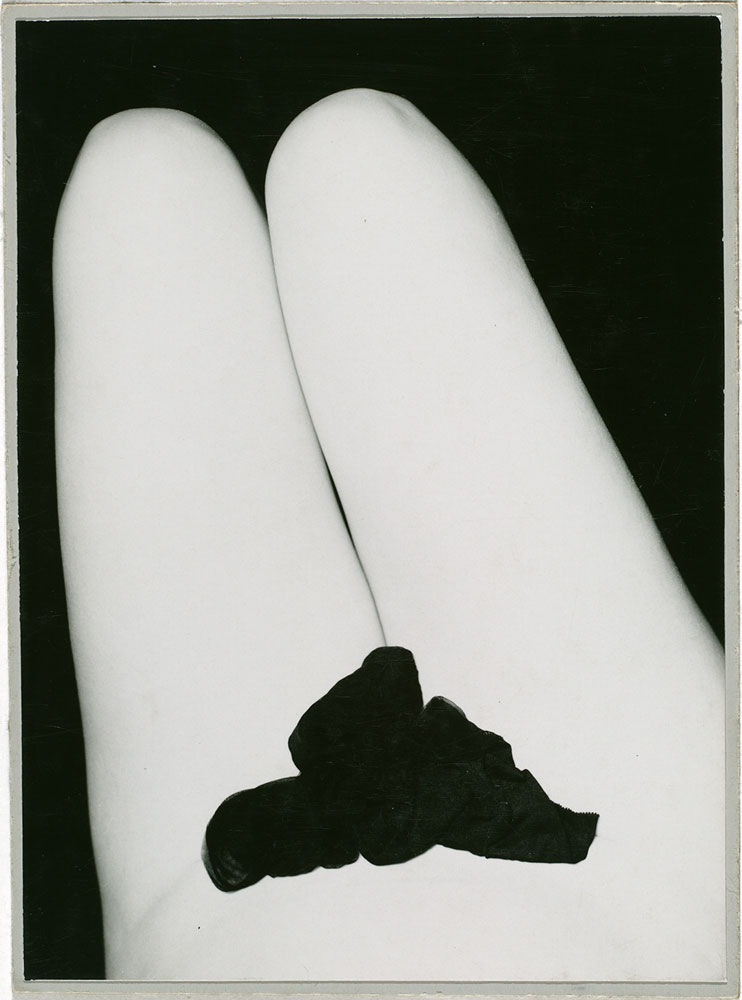

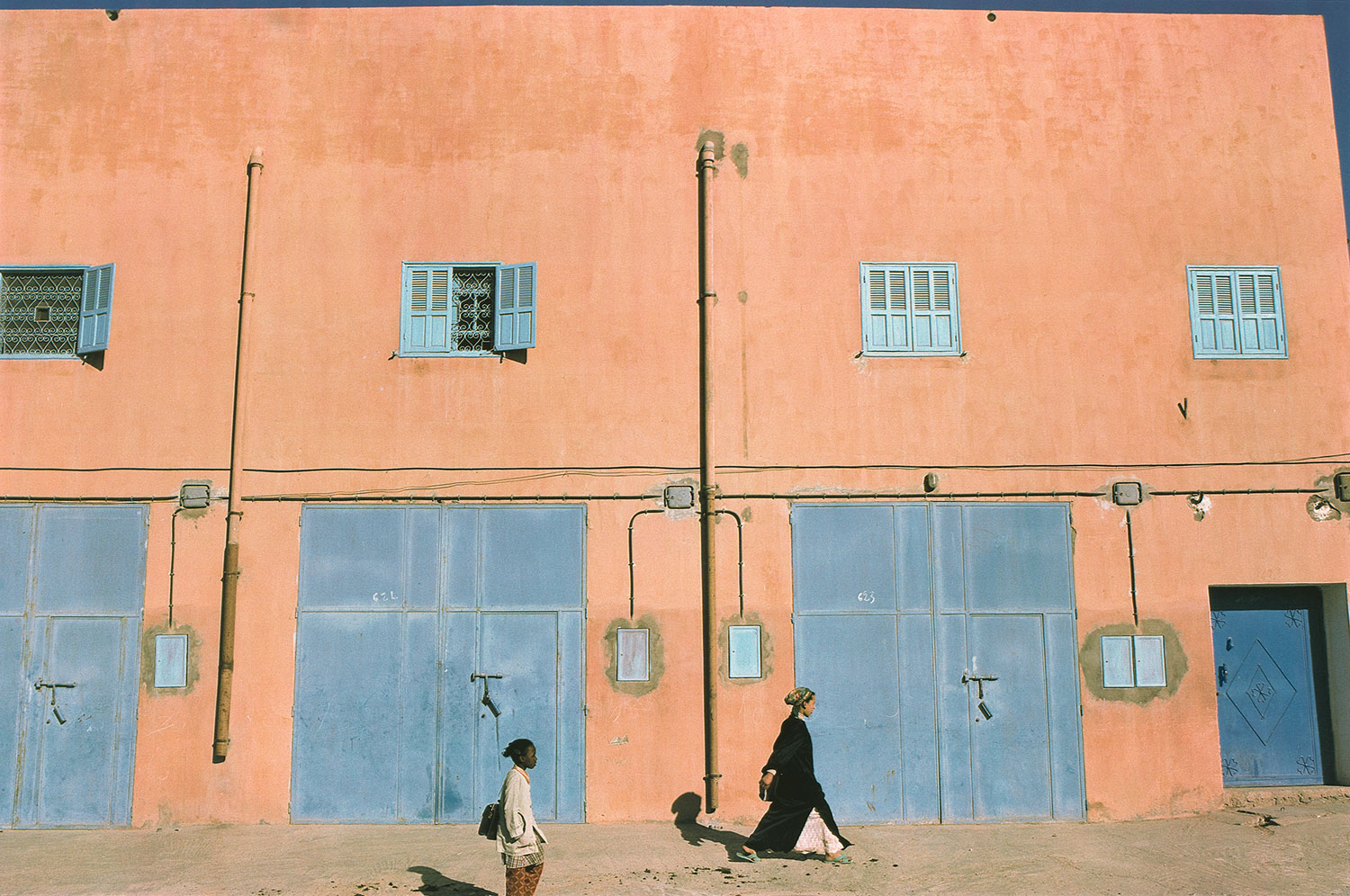

Harry lived to make photographs. Nobody took greater delight in seeing what things looked like when photographed than Harry Callahan. He would use his particular vision to transform simple things into really compelling photographs that intensified the subject matter. He had three areas he photographed: His wife Eleanor and daughter Barbara, nature, and the city—his three loves. What made Harry really special was that he could stick to those few subjects and create an enormous body of work. He worked every day.

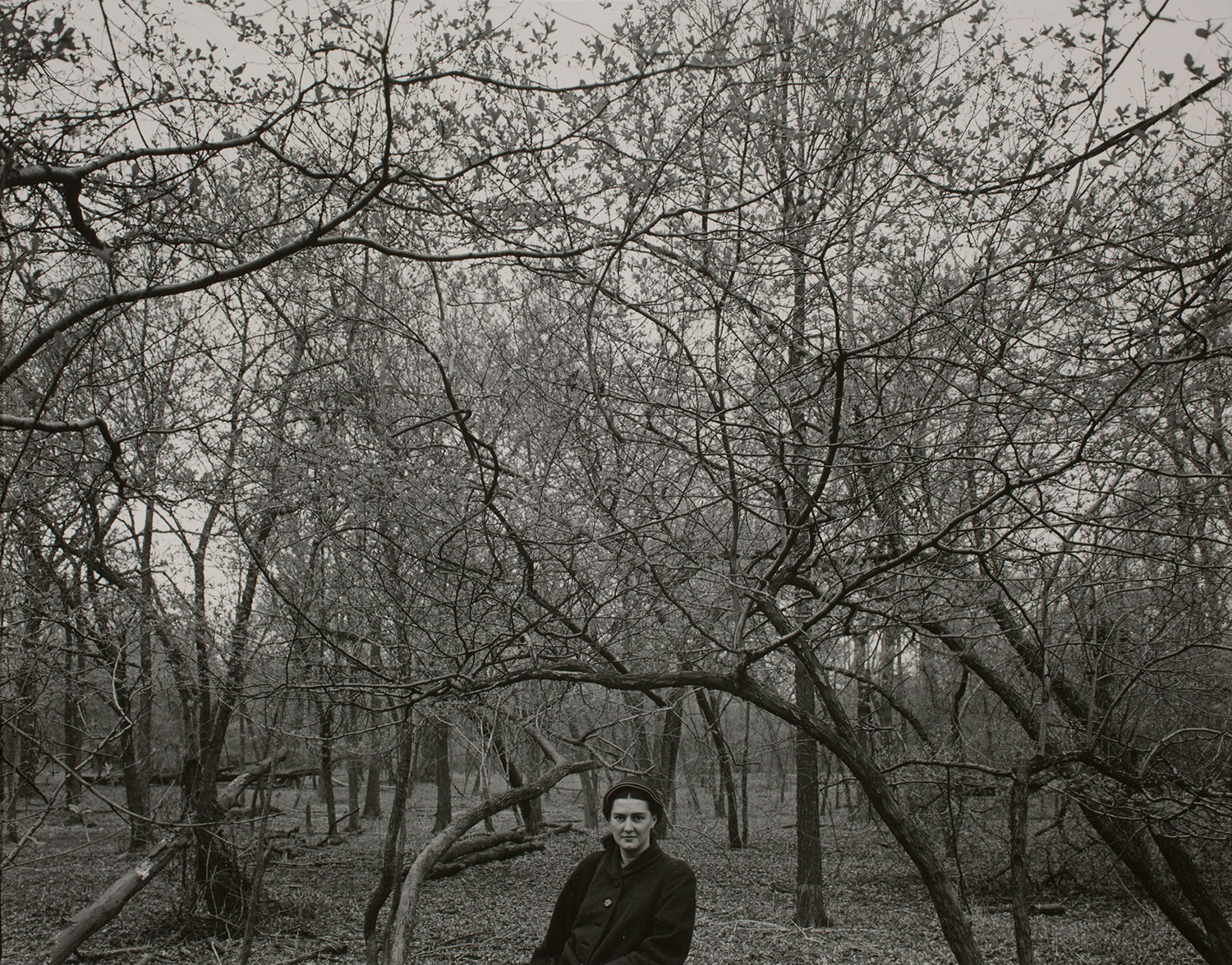

One of my favorite images from this exhibition is an 8 x 10 contact print of Eleanor in the woods. The picture has an incredible, complex background of trees—not at all unlike what the abstract expressionists were doing in their paintings—and in the middle of it is Eleanor. It is a compelling portrait, as Harry placed Eleanor in very complex backgrounds but, because of Harry’s ability to see things clearly, the picture registers in a very powerful way.

Harry’s clarity of vision and his straight-forward approach to making pictures is what separated him from other photographers. He would see something that’s a part of our everyday world, and bring it to us with a remarkable aesthetic. Someone just walking into this exhibition [which is curated by Sarah Greenough] or someone who doesn’t know a lot about photography can still see this remarkably clear and consistent vision of the world. That’s what people will relate to in the show.

Harry had a stroke in 1996 and he had to teach himself to write again—he was felled and had difficulty talking. After he died, I helped Eleanor and Barbara straighten up the studio, and in the dark room was a box with a post-it note on it. The post-it read, “Peter—Next Show.” Even in his limited capacity—he couldn’t photograph or print everyday—he was still working with pictures. And that spirit is astonishing; it really sums Harry up.

Harry Callahan at 100 is on display from Oct. 2, 2011-March 4, 2012 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Peter MacGill is a photo representative and gallery owner in New York. In 1983, he founded Pace/MacGill Gallery in collaboration with partners Arne Glimcher of The Pace Gallery and Richard Solomon of Pace Prints and Pace Primitive.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Behind the Scenes of The White Lotus Season Three

- How Trump 2.0 Is Already Sowing Confusion

- Elizabeth Warren’s Plan for How Musk Can Cut $2 Trillion

- Why, Exactly, Is Alcohol So Bad for You?

- How Emilia Pérez Became a Divisive Oscar Frontrunner

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Zelensky’s Former Spokesperson: Ukraine Needs a Cease-Fire Now

Contact us at letters@time.com