On the afternoon of September 11, Pittsburgh-based photographer Scott Goldsmith was one of first journalists allowed to view the crash site of United Flight 93, which had been 20 minutes away from its target, Washington D.C., when passengers and crew fought the terrorists, bringing the plane on a field near the small farming town of Shanksville, Pa. “The fire had been so severe there was no aircraft left,” says Goldsmith, describing the crash site as it looked just hours after impact. “By the time we got there, there wasn’t even any smoke. Just eight or nine men in white protective suits moving around a crater, with a line of trees behind them, burnt black.”

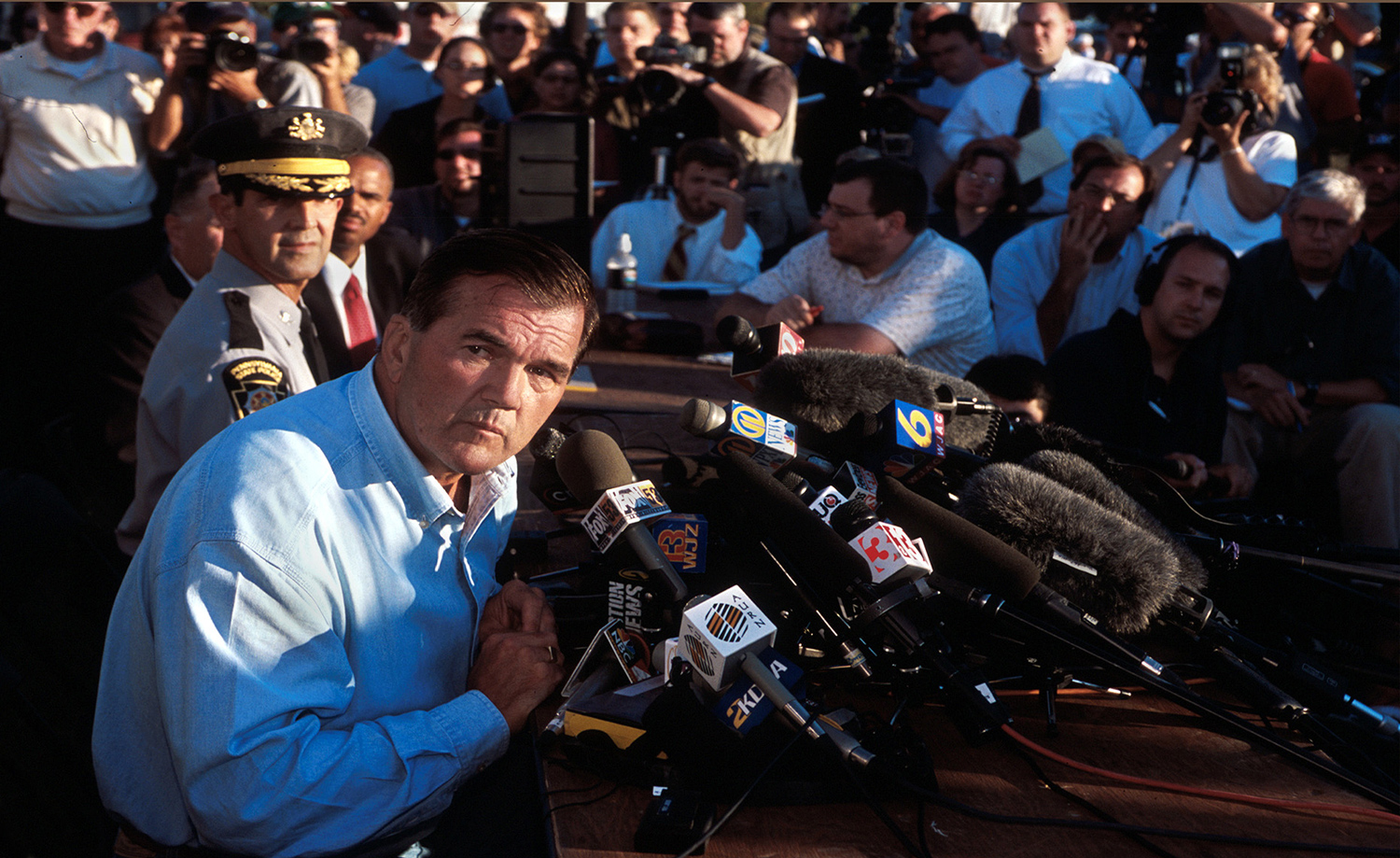

Goldsmith continued working until Governor Tom Ridge’s press conference at sunset, returning home in time to catch Federal Express and dispatch the film to US News & World Report.

But the sense of what had happened at Shanksville lingered. As the media focused on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon, “I felt Shanksville was forgotten,” says Goldsmith.

So he kept returning to document the town: the tourists, the government officials, the FBI and other technicians conducting the investigation. He’s made the trip about twice a year, for ten years, getting to know many of Shanksville’s 250 residents. “The town just grew and grew on me. And working there helped me deal with the event,” says Goldsmith, who is turning the project into a book. “Shanksville is something meaningful to me. And those sort of stories are far and few between when you’re trying to make a living in this business.”

Goldsmith, who has covered everything from the campaign trail to shale drilling, says this was the first story he immersed himself in at such length. As he pursued it, his budding relationships with the locals allowed him to meet a man who witnessed the plane smashing into the earth, and hear how he wasn’t able to leave his house for two weeks. He got to see how the scene continued to unfold, “people would come up to me with a handful of shredded cloth that looked like it may have been plane seats,” says Goldsmith “and say, ‘look what I found in my field.'” And he was let into areas that were supposed to be off-limits. “Wally Miller, who owns a funeral parlor, and helped a lot of the families of the victims, took me back behind police lines,” says Goldsmith, “and let me photograph trees near the site.”

For the most part, Goldsmith has had the story to himself. “It’s not like Ground Zero where no matter what time of day you go,” says Goldsmith, “someone is always there.”

That may soon change, as the National Park Service works on a memorial, with the first phase of construction completed on the 10th anniversary. Incorporating groves of trees, and a 93 ft. tower with 40 wind chimes, the park is designed to represent the passengers and crew who, as Elizabeth Kemmerer, whose mother was on board, said to the 9/11 Commission, “fought a battle at 35,000 ft., in an aisle no wider than 3 ft.”

As work on the park goes on, the thousands of people who visit the area over the last 10 years have set up their own tributes—writing messages of gratitude on guard rails, and leaving flags, jewelry, even Purple Hearts near the site. They were there when Goldsmith returned to gauge reaction to the killing of Osama bin Laden. There weren’t jubilant celebrations like the ones that erupted in Washington and New York. Rather there was a muted sense of relief. “They don’t want to be in the limelight,” says Goldsmith. “That’s why they chose to live there. But all of a sudden, they became part of our history.”

To see more of Goldsmith’s work, click here.

To visit TIME’s Beyond 9/11: A Portrait of Resilience, a project that chronicles 9/11 and its aftermath, click here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com