If there were no Mississippi Delta, there would be no blues. The music welled up from the cotton fields and sharecropper shacks of the late 19th century as an eerie and elemental force. Bandleader W.C. Handy didn’t mind being called the father of the blues a generation later—it was good for business—but he acknowledged that the music was already full grown when he encountered it in 1903. Sleeping on a bench in the “colored” section of a Deep South train station, Handy woke to the sound of a man playing a guitar, bending and sliding the notes by pressing a knife over the strings.

But if the blues had’nt left the Delta, the music would not have changed the world. It moved with the great migration of American blacks out of the Jim Crow South. The blues crept upriver to Memphis and St. Louis and overland to Kansas City, Chicago, Detroit and New York. Everywhere it went, the blues grabbed people just as it had grabbed Handy in that train station. It took hold of a leather-lunged horn player named Louis Armstrong who turned the blues into jazz. It seized a Jewish songwriter in New York, George Gershwin, who wrote a classical rhapsody and painted it blue. The blues got into the hollows of Appalachia and spawned bluegrass. Elvis wasn’t Elvis until he got the blues. The blues swam an ocean in search of young artists with names like Lennon, McCartney, Richards, Jagger, Clapton, Beck and Morrison.

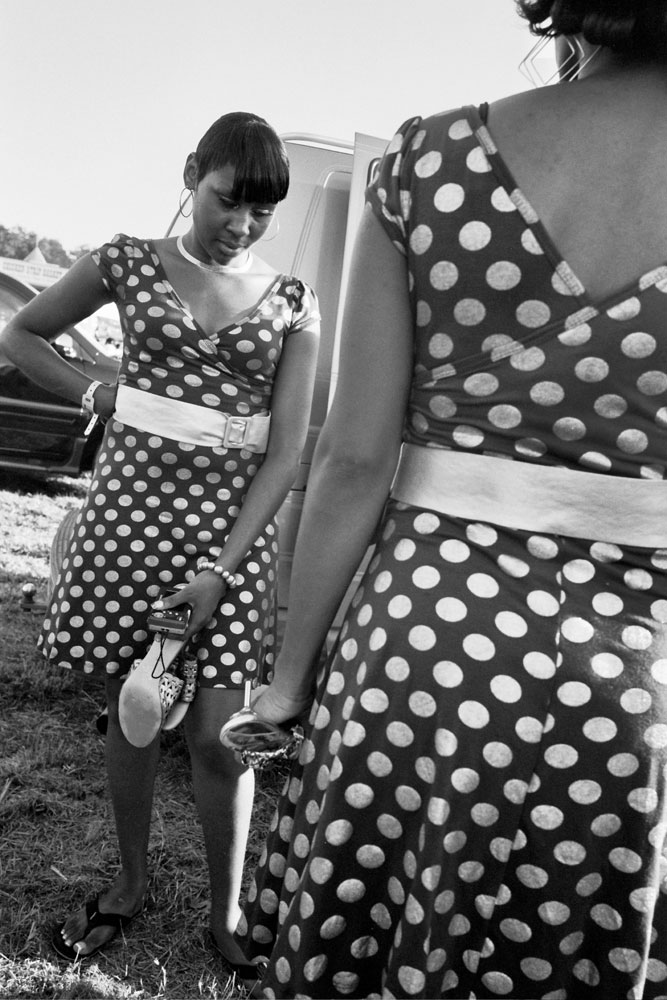

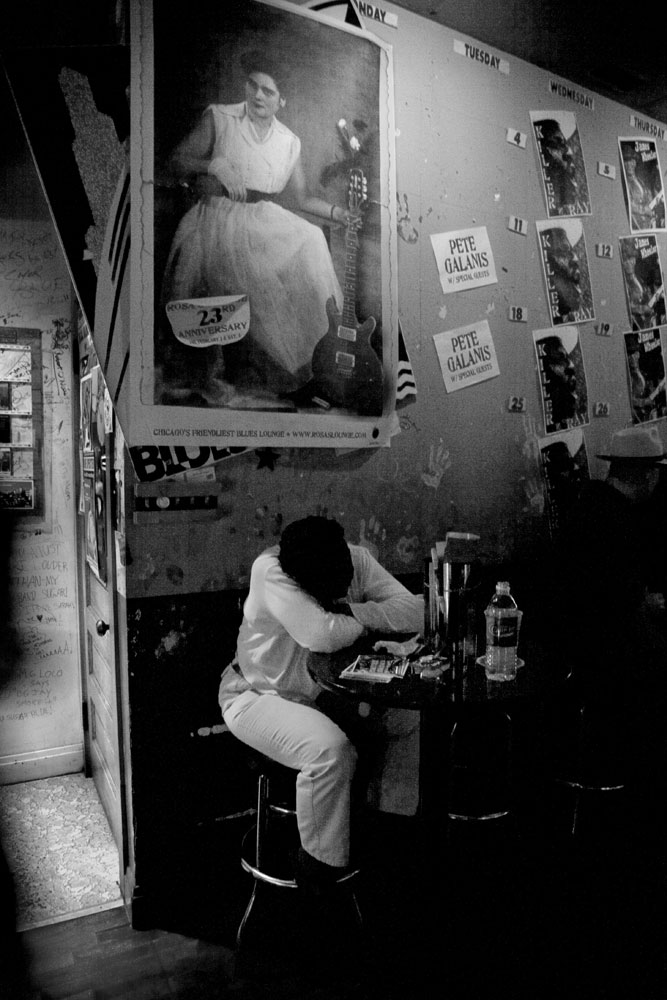

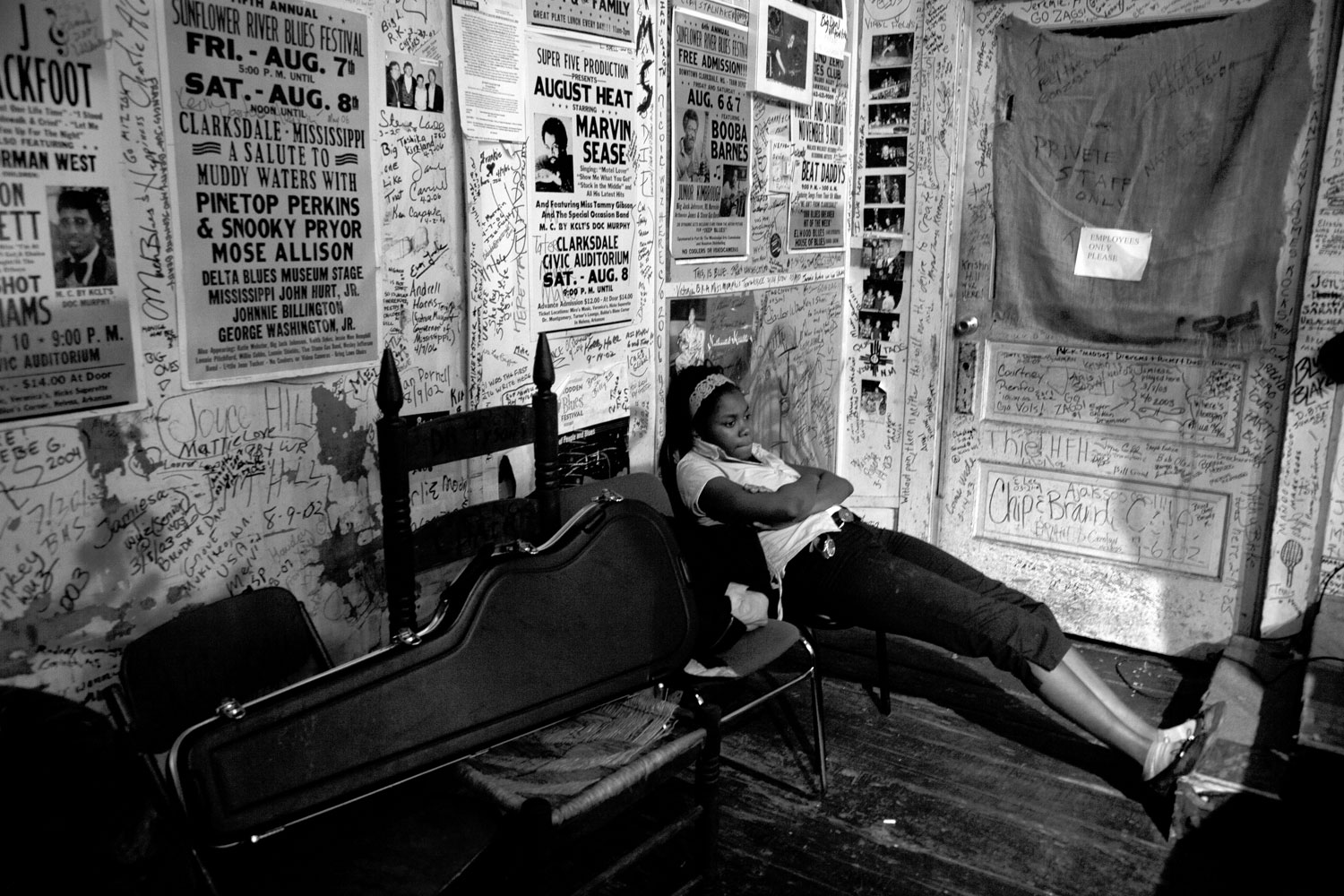

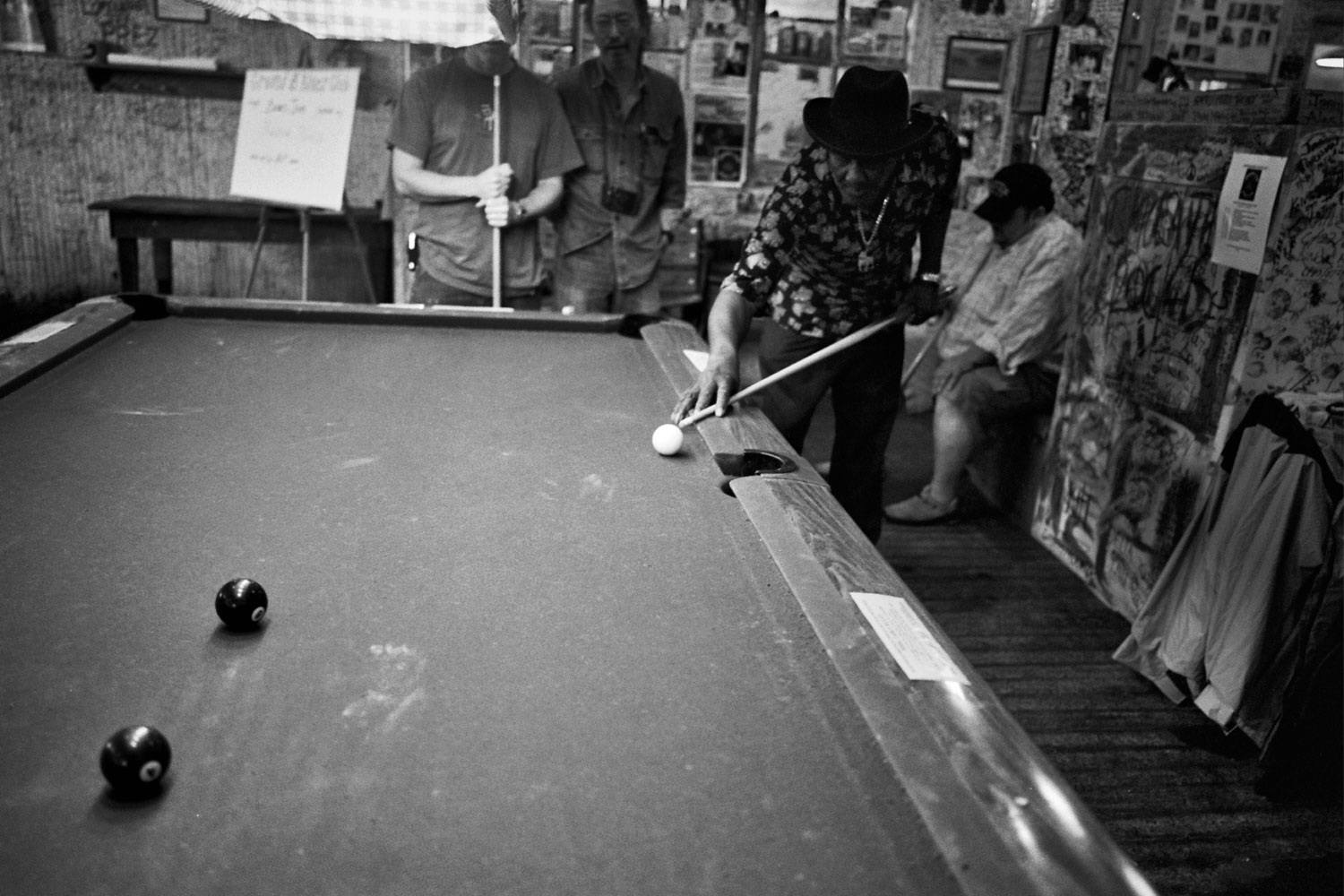

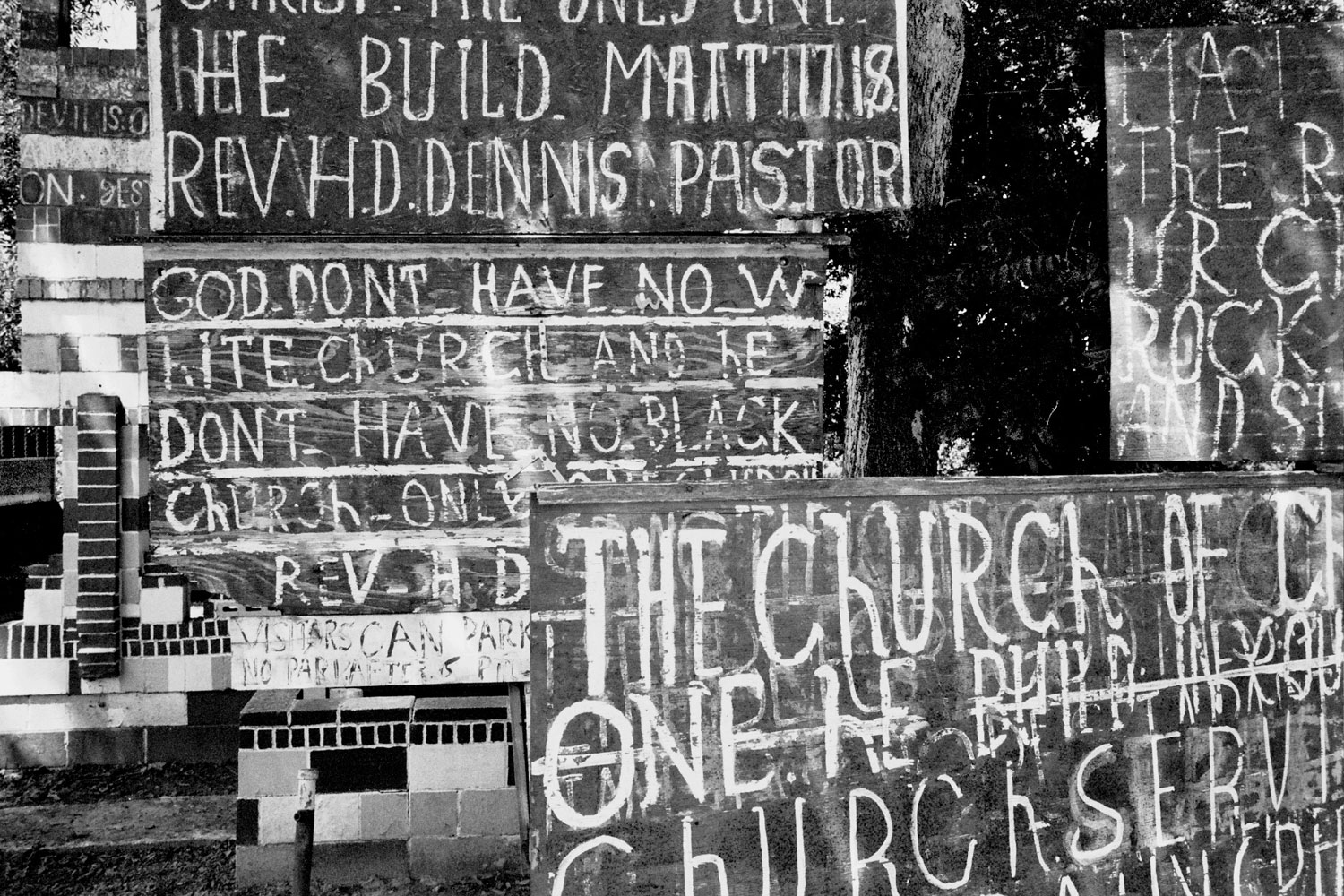

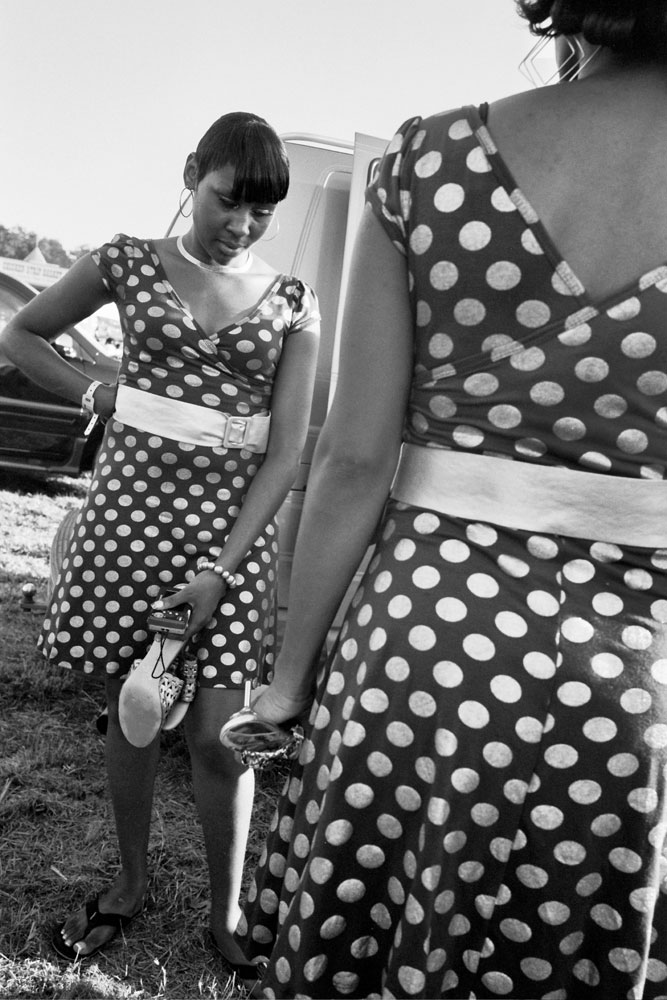

Now it’s the musical equivalent of oxygen—everywhere and nowhere. Photographer Ed Keating set out a couple of years ago to follow the blues path back toward the origins. He began in Chicago, the stormy, brawling city that once drew Delta bluesmen northward like a mighty magnet. From that mecca—home to Big Bill Broonzy, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Elmore James, Blind Lemon Jefferson and on and on—Keating headed south, retracing the steps, taking pictures in the appropriate hues of black and white.

For a New York kid who grew up on the blues, blowing a mean mouth-harp from age 14, this was a trip home—the home of the spirit. Keating wound up Clarksdale, Miss., which is as close to the birthplace as you can get. And there, something almost mystical happened.

You see, Clarksdale is the town nearest to the little shack where a fellow named Eddie “Son” House was born around 1902. Son House played the blues with otherworldly genius; of all the musicians bending and sliding their notes in the Delta, he was the one favored by Charlie Patton. And Patton takes us even farther back, to a plantation house in the Delta circa 1890. This is the place and time where the music really got started. If Charlie Patton wasn’t the father of the blues, he surely sat on a porch with the man who was.

In the mid-’20s, when Charlie Patton played the blues with Son House, a kid named Robert Johnson was in the audience. He had a guitar and tried to join in; no one heard much promise there. But not long afterward, House and the bluesman Willie Brown heard Johnson play again. Suddenly the kid was so scary good that a legend was born, saying that Johnson, at a lonely crossroads on Highway 61 near Clarksdale, traded his soul to the devil for the gift of the blues.

Now, 80 years later, Ed Keating pulled into a Clarksdale parking lot. As he opened his car door to get out, he noticed an elderly man getting into a nearby car. He came that close to missing the old man, who turned out to be Honeyboy Edwards, the last living musician known to have played with Robert Johnson. (Edwards died last month at 96.)

In that moment, everything converged. A human path connected Keating to Edwards, then to Johnson, to House, and finally to Patton in a chain of living art. Meanwhile, a physical path had been retraced connecting the cotton fields to the cosmopolitan city. These tied into the spiritual path that transformed the music of scorned fieldworkers into music for the whole wide world. Keating’s journey—and these very bluesy pictures he made to document the trip—remind us that art is universal precisely because it is specific. It speaks to what we share.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com