The photos in Boris Mikhailov’s book “Case History” form a raw and deeply felt response to the decline of his hometown of Kharkov, Ukraine following the collapse of the Soviet Union. A selection of the work, curated by Eva Respini, will be on display in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City from May 26 to September 5.

Mikhailov (b. 1938) is one of the leading photographers to emerge from the former USSR. For decades, his work has, to quote Respini, “explored the position of the individual within the mechanisms of public ideology”—even after that ideology crashed to the ground.

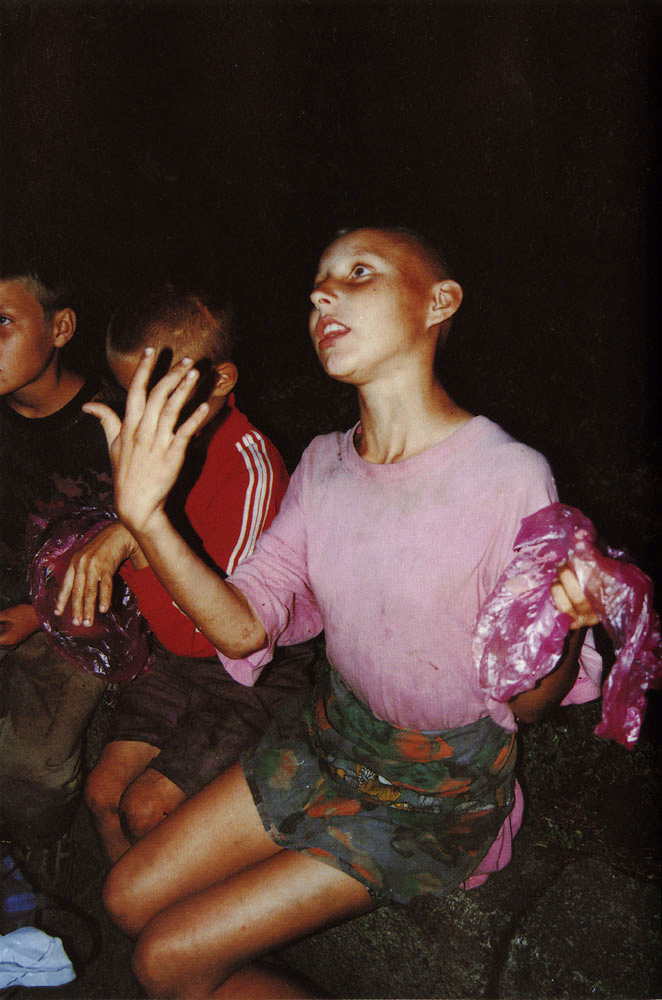

Having lived in Germany for a period, the artist returned to Kharkov, Ukraine, several years after the fall of communism. He describes the trip which inspired this work: “Devastation had stopped. The city had acquired an almost modern European center. Much had been restored. Life became more beautiful and active, outwardly (with a lot of foreign advertisements)—simply a shiny wrapper. But I was shocked by the big number of homeless (before they had not been there). The rich and the homeless—the new classes of a new society—this was, as we had been taught, one of the features of capitalism.”

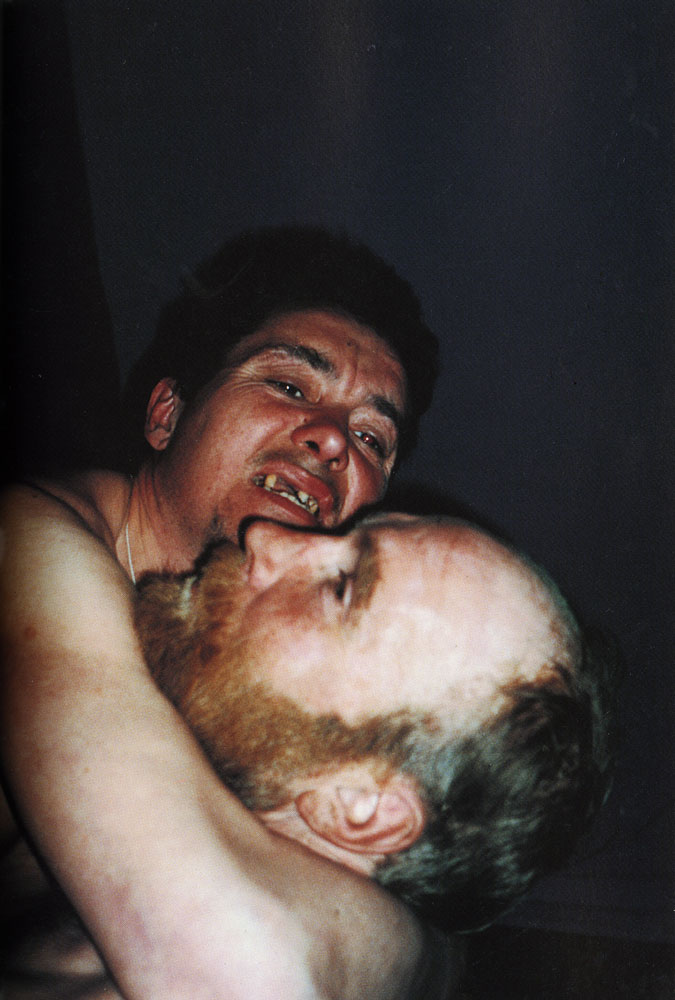

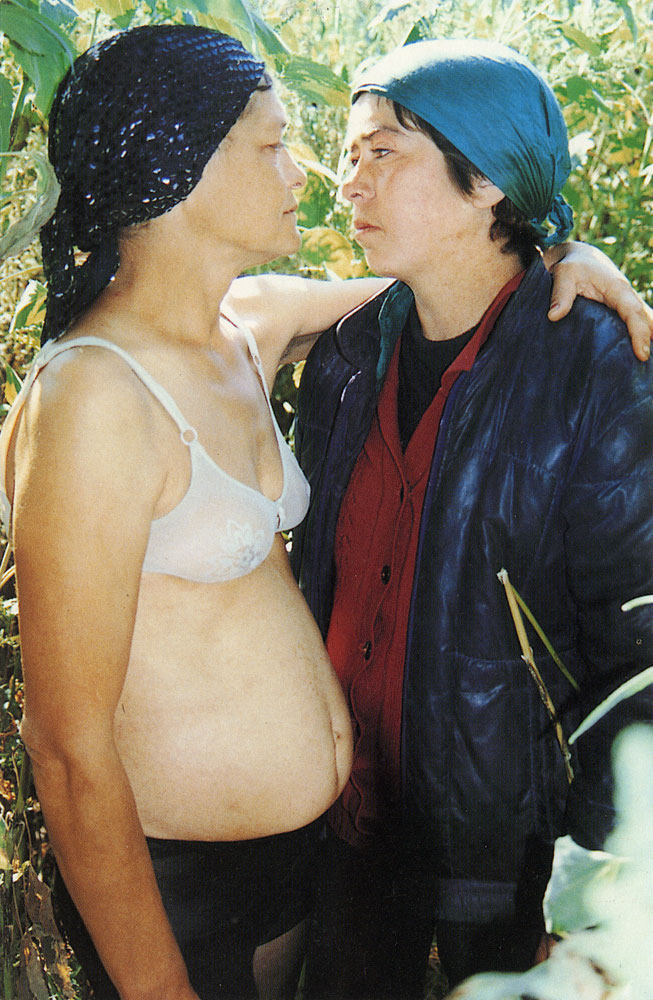

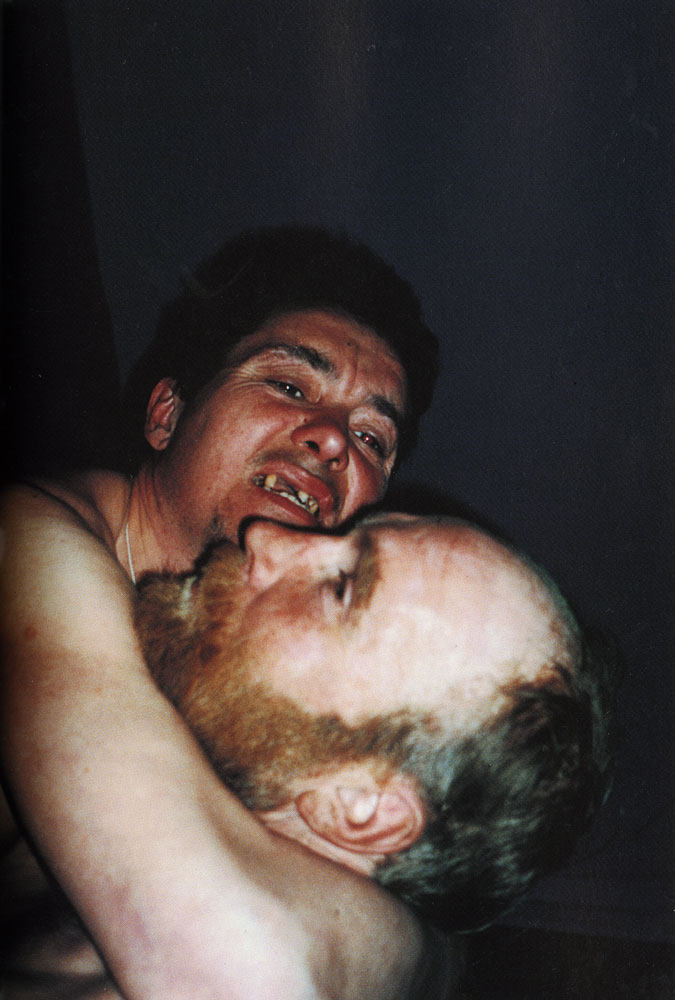

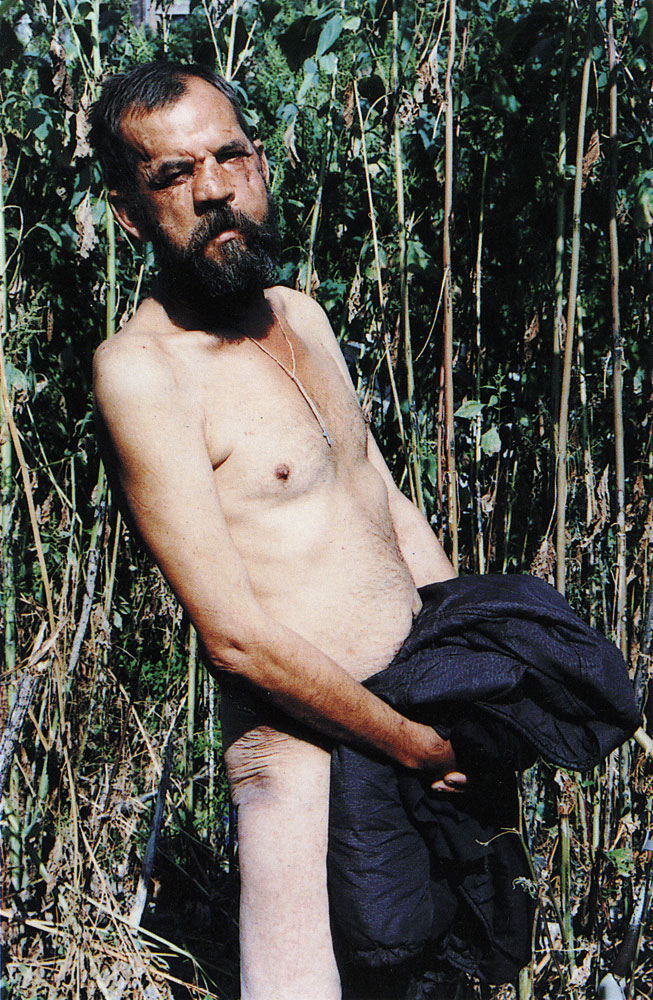

The work itself can be difficult to look at. The color, life-size prints are unsparing in their documentation of the disease and frailty of Mikhailov’s subjects, and the grit and grime of their humble surroundings. Directed to stand naked, clothes in hand, some appear, in his words, “like people going to gas chambers.” Others share heartbreaking moments of tenderness, while a few appear comatose with drink.

While the subject matter may recall photojournalism, Mikhailov’s work diverges from it in at least one major way—Mikhailov paid his subjects to pose for him. Traditional photojournalists balk at the notion, believing that paid subjects will give them a performance instead of honesty.

“As I understand it,” Respini says, this is “a question that has taken Boris by surprise. I think he felt that paying his subjects was absolutely the right and the moral thing to do. These are people who need support and need help. In fact, he did more than just offer them money—he offered them his home, they showered in his apartment, he offered them warm meals. If he was going to spend a year photographing this community of people, he wanted to be involved with them as more than just a bystander, a voyeur, but really to collaborate with them on a one-on-one basis.” In any case, Respini continues, “For Boris…there is no such thing as a pure document that is free from any manipulation.”

Living at the intersection of fine art and documentary, Mikhailov’s work has invited controversy yet refuses to yield the moral high ground. Says Respini, “The camera is an extension of the photographer, but the camera is also an extension of the viewer, and as soon as you come into that place, you’re complicit too, into the society that allows this kind of community of people to exist on the margins.”

—Myles Little. Produced by Vaughn Wallace.

For more information about the show, visit MOMA.org.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com