Curated by photo editor Elisabeth Biondi and photojournalist Enrico Bossan, the five-day event aims to highlight the changing state of documentary photography.

Post updated May 14, 2011.

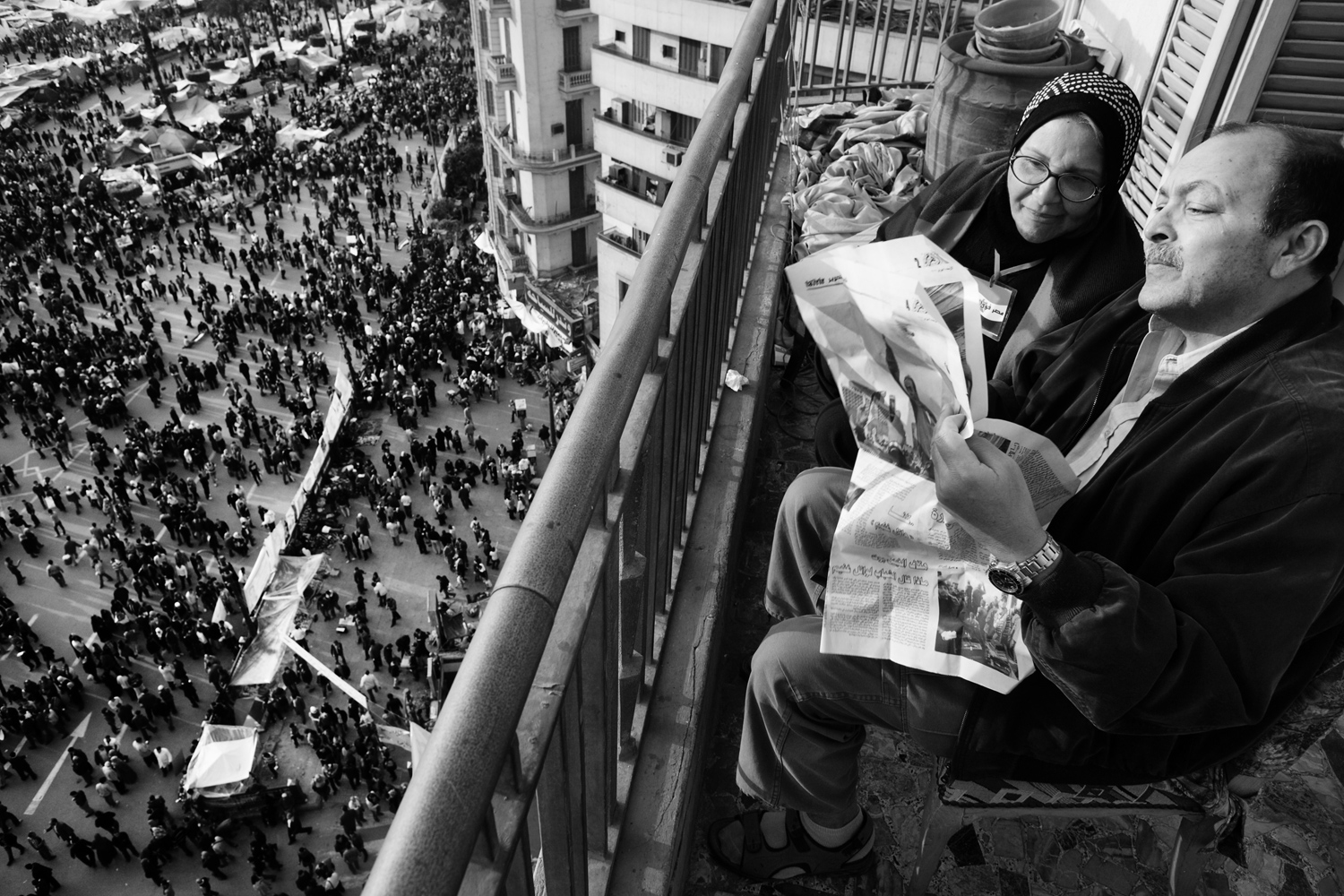

On Thursday night, the NYPH celebrated Under the Bridge: Projections of a Revolution, which spotlighted photos and videos from the recent revolutions in North Africa. Attendees gathered to hear music from DJ Awesome Tapes from Africa and see images projected onto the archway under the Manhattan Bridge. A silence fell over the crowd when the slide show stopped to honor Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, two photojournalists who were killed on April 20 while photographing the conflict in Libya.

“There are no more discoveries to be made,” Elisabeth Biondi tells me on the opening night of the fourth annual New York Photo Festival. “Anyone can take a picture now, so it’s forced documentary photographers to have a more personalized vision.”

It’s that changing state of photojournalism that’s the theme of this year’s festival, which runs through May 15 in Brooklyn’s DUMBO neighborhood. Founded in 2008 by powerHouse Books publisher Daniel Power and former managing editor of VII Photo Agency Frank Evers, the five-day event will showcase more than 3,000 photographs displayed in several warehouse spaces, as well as multimedia shows and artist lectures. But the main exhibitions, curated by Biondi and photojournalist Enrico Bossan, are presented under a shared theme, PHOTOGRAPHY NOW: engaged, personal, and vital.

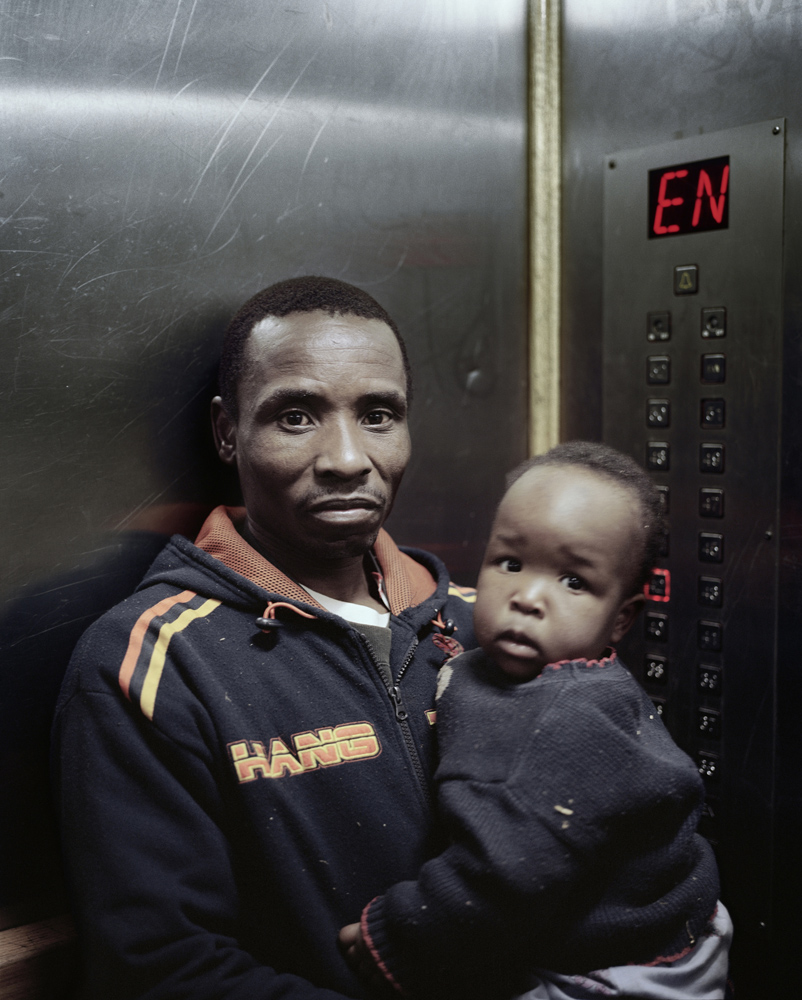

Biondi’s looked at thousands of photos throughout her decades-long career as a photo editor (she left the New Yorker this March after a 15-year tenure). But the variety and strength of photojournalism sparked her interest anew when she was judging a photography awards show last year in London. “This sort of dichotomy between the really creative output being so strong and, on the other hand, the economic climate being so dire, struck me,” she says. “I thought, ‘How did these photographers get there?’ because we knew that assignments are rare these days.” Her portion of the exhibit, called Subjective/Objective, features the work of 10 photographers on issues ranging from the urbanization of Mongolia’s schools to post-traumatic stress disorder.

Meanwhile, Bossan’s show, Hope: between dream and reality, also surveys a host of issues, among them the Bosnia genocide and Mexico’s drug war. But the exhibit is focused on a group of young photographers Bossan has followed for nearly five years. “The young generation today is just in time with what’s happening around the world,” he says. “What I like about them is how they push to change the ideals of photography.”

And for those young photographers who want to change—or at least shift—the art form, Biondi says there’s no better time than the present. “Creatively, the rules are no longer that strict about documentary photography. The borders have been widened and photographers can have their own voice much more than they were ever allowed traditionally.”

— Reporting by Feifei Sun. Produced by Vaughn Wallace.

More information on schedules, exhibitions and lectures is available on the Festival’s homepage.

Exhibition Hours:

Wednesday, May 11 – 5:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m.

Thursday, May 12 – 12:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m.

Friday, May 13 – 11:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m.

Saturday, May 14 – 11:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m.

Sunday, May 15 – 11:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com