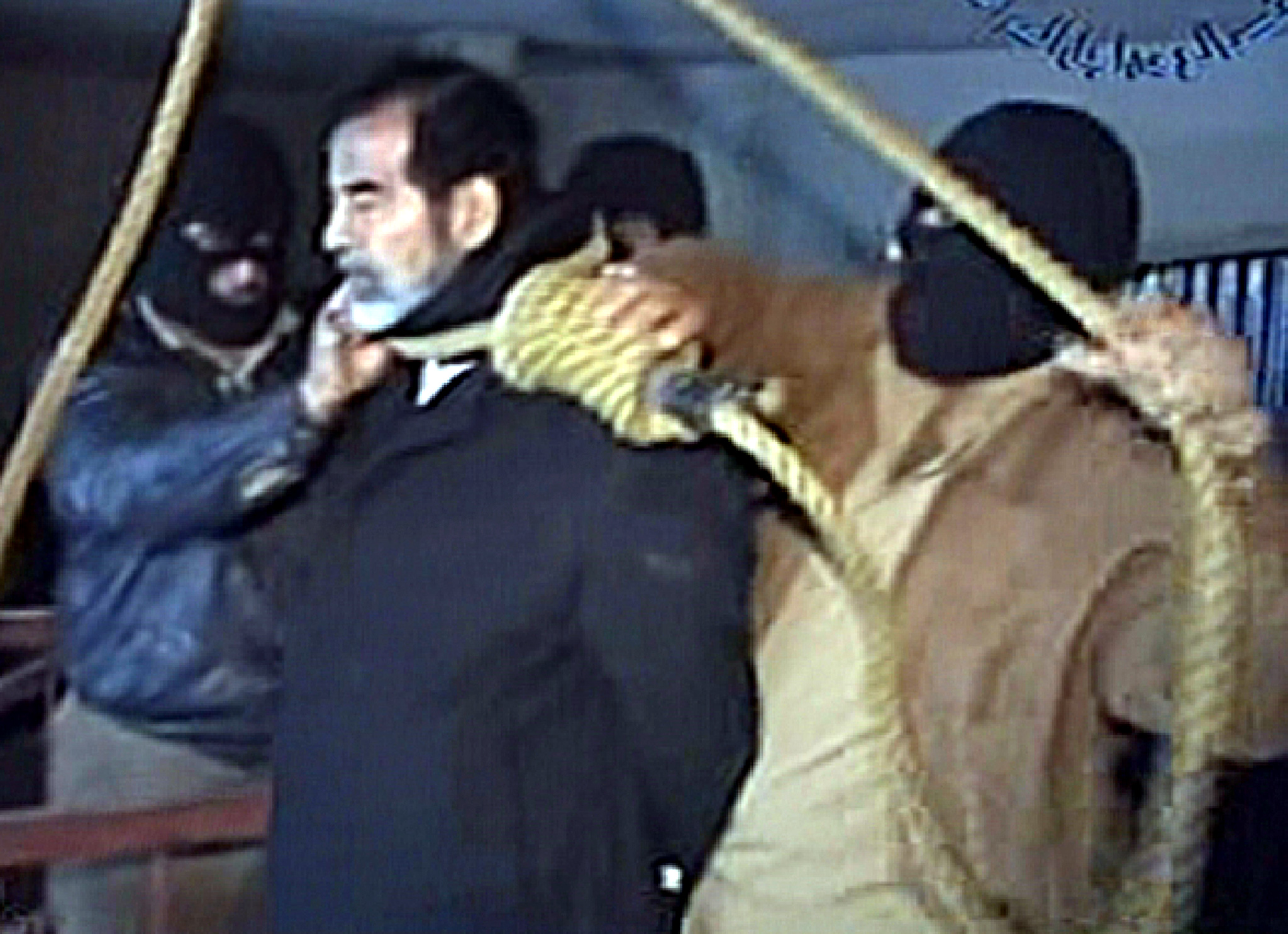

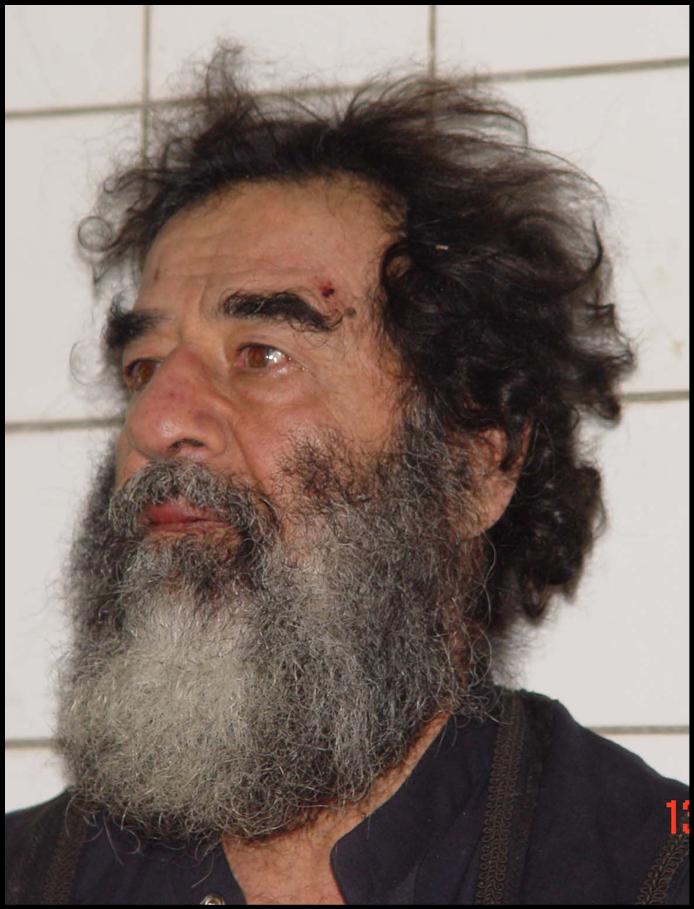

When President Obama announced last Wednesday, May 4, that he would not release images of the dead Osama bin Laden, the decision seemed anomalous. When a most-wanted fugitive at such a level of notoriety is captured or killed, it is customary to release photographs of the deceased as evidence, and these images often have tremendous propaganda value. When Saddam Hussein’s sons Uday and Qusay were killed in a raid by U.S. soldiers in 2003, images of their bloodied corpses were widely disseminated, and when their father was eventually captured, tried, and hanged, images of that episode also emerged.

But there are risks to such exposures, since these images do not always have the effects their perpetrators wish. When Che Guevara was executed by the Bolivian army (aided and abetted by the CIA) in 1967, his mutilated corpse was proudly displayed to the world press. But the resulting postmortem images had the opposite effect of what was intended, eliciting widespread compassion for the slain revolutionary and revulsion toward his killers.

Osama bin Laden was no Che, but he was an extremely charismatic figure and a master of iconopolitics who meticulously crafted and controlled his image, and that image will be around for a long time. So the handling of his image upon his death at the hands of the Americans had to be very carefully considered. The public desire for these images was so strong that fake images of bin Laden’s bloodied corpse appeared all over the Internet immediately following the announcement of his death.

President Obama’s stated rationale for withholding the real images of bin Laden in death was that their release could endanger American troops in Iraq and Afghanistan. This was the same reason he gave two years ago when he decided to continue the Bush Administration’s policy of refusing to release detainee-abuse images from Abu Ghraib, reversing a previous agreement the government had made with the American Civil Liberties Union to release the images. At the time, I agreed with Judge Alvin K. Hellerstein of the U.S. District Court in Manhattan, who ruled that the public’s right to know outweighed such a vague, speculative fear of danger to the U.S. military, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld that ruling. I argued that the actions depicted in the Abu Ghraib images were not isolated incidents carried out by “a few bad apples” but were in fact the result of policy decisions made far up the chain of command. This meant that the Abu Ghraib activities were being done in our names, with our implicit support as participants in a democracy, and we needed to know and see exactly what was done so that we could bring those responsible for it to justice.

“In any case,” I warned then, “history shows us that iconoclasm generally doesn’t work. When you try to destroy or censor images, those images gain power rather than losing it and often come back to haunt their suppressors.”

But even though the reason given for withholding the images is the same, the two cases are dissimilar. It is more difficult to see what would be gained by releasing images of bin Laden dead. Americans know what was done in their names by Seal Team 6 in Abbottabad, and most accept it. We had been waiting for it for almost 10 years. Images of bin Laden’s corpse would do nothing to dispel the doubts of hardcore skeptics (as Obama recently discovered after releasing a copy of his birth certificate), and they would almost certainly be used by bin Laden’s present and future followers to garner support for his murderous agenda. If the images had been released this week, everyone would be talking about them today instead of about the victims of 9/11.

I believe that President Obama took the wrong lesson from the example of the Abu Ghraib images [EM] and that he may be making the right decision about withholding the images of the dead bin Laden … for the wrong reasons.

David Levi Strauss is the author of From Head to Hand: Art and the Manual (Oxford University Press, 2010), Between the Eyes: Essays on Photography and Politics, with an introduction by John Berger (Aperture, 2003), and Between Dog & Wolf: Essays on Art and Politics (Autonomedia, 1999, and a new edition with a prolegomenon by Hakim Bey, 2010). He is chair of the graduate program in art criticism and writing at the School of Visual Arts in New York.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com