War crimes are as old as war, and thus as old as mankind itself. Homer’s Iliad—Western civilization’s first great work of literature—is about one, after all. It chronicles Achilles’ inexorable moral collapse during the last days of the Trojan War. His prolonged ethical erosion and self-debasement culminates in a vile transgression: the desecration and mutilation of Hector, Troy’s greatest hero, whom Achilles had just vanquished in battle.

But one variety of repugnant battlefield behavior—a twist on the timeless yet now morally unacceptable practice of plundering enemy corpses for keepsakes, whether equipment or flesh—is uniquely modern: the trophy shot. Allegations that a small band of U.S. soldiers had gone spectacularly and murderously rogue in Afghanistan in 2010 and killed up to four innocent civilians with depraved premeditation had barely caused a ripple of outrage even though news about what has come to be known as the “Kill Team” case started leaking out last May.

It required pictures, first published by Der Spiegel and then Rolling Stone, to really focus the world’s attention on the case. The photo of one smiling soldier holding the head of a recently killed Afghan up for the camera is so inflammatory—with a grinning American appearing to enjoy the death of another human being—that comparisons to some of the more shocking photos from the Abu Ghraib scandal (such as Army Spc. Sabrina Harman and Army Spc. Charles Graner Jr. giving a thumbs up next to refrigerated corpses) were immediate and obvious.

The fact that the Kill Team photos were apparently by-products of the cold blooded murder of innocent civilians makes them especially disturbing, but what about the practice of taking trophy photos in general, even when the subject is a legitimately killed enemy combatant? How widespread is that? How often do soldiers do it? Why do they do it?

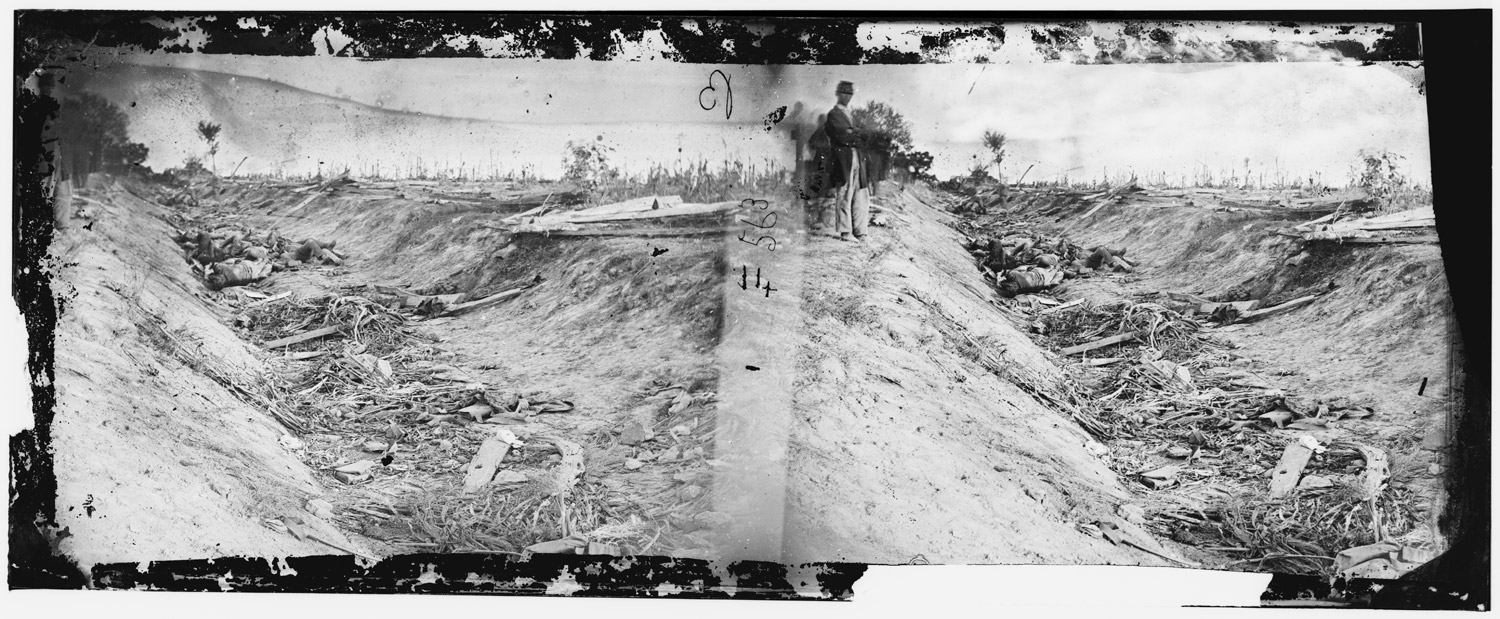

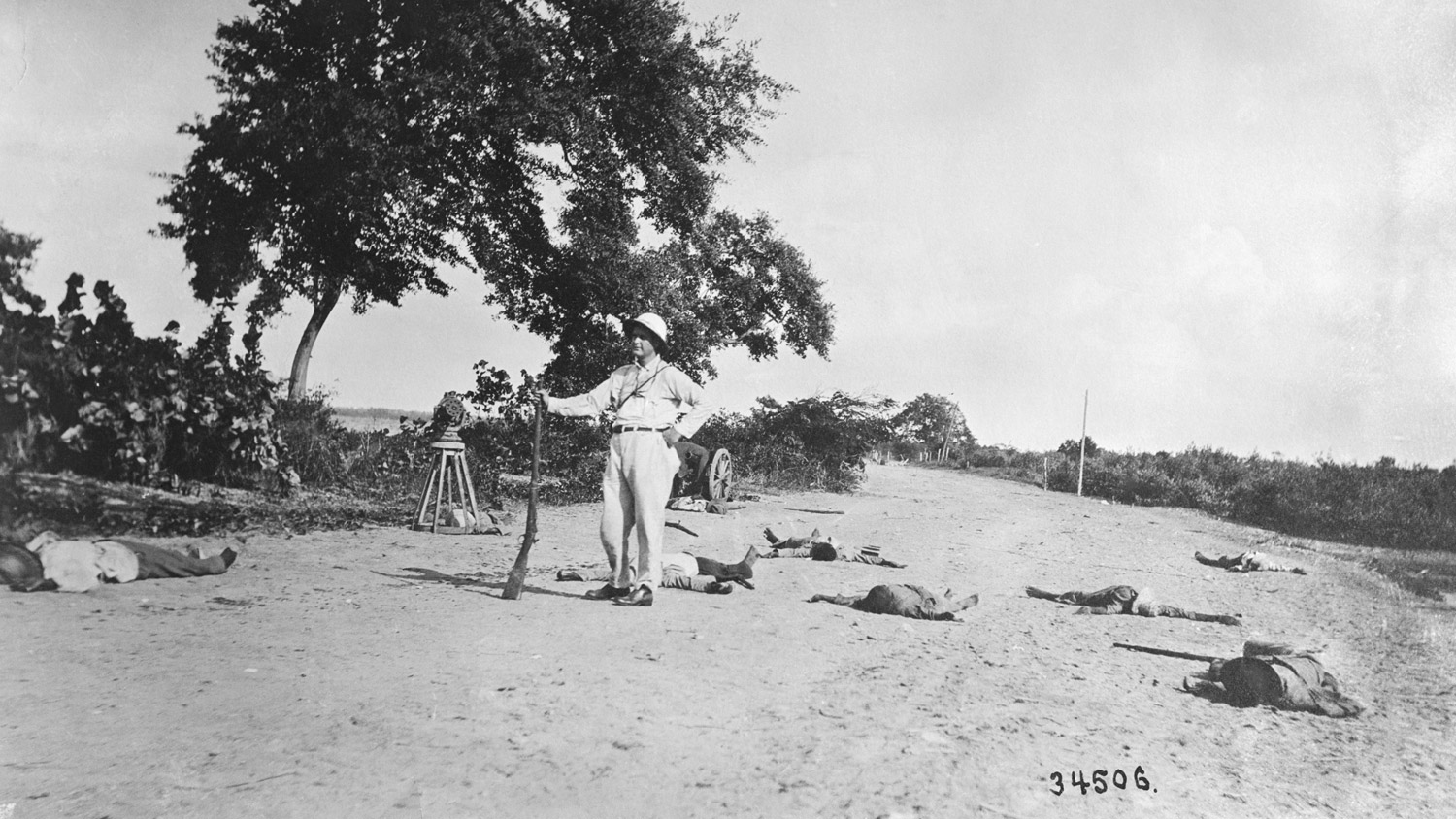

Looking through photographic history, one thing is clear: If war crimes are as old as war itself, then the trophy shot is as old as cameras have been on battlefields. Delving into various archives, TIME International Photo Editor Patrick Witty had no trouble putting together a selection of photographs that fit our loose, on-the-fly definition of a trophy shot: soldiers posing next to dead bodies with a demeanor that appears if not celebratory then at least unbothered, content, happy. He found pictures from the American Civil War to the ongoing conflict in Afghanistan.

They are hard to look at. But they are also hard to really understand. The unfathomability of warfare among those who have not lived through it in no way excuses what, from a safe remove, are morally objectionable behaviors. But an appreciation of just how traumatic and dehumanizing prolonged combat can be is a useful exercise in compassion and empathy. There are few practices in human existence more elemental, and few harder for those who have not experienced it to comprehend, than the stark contest of armed combat. Warfare—by design—cheapens the value of human life. Are we really so surprised, then, that soldiers—no matter their nationality, creed or color—frequently take a more cavalier attitude toward the dead than broader society? In earlier eras, a soldier’s delight simply to be alive, and a frequently understandable hatred of enemy, used to result in a stripping of the foe’s body of armor. In more modern times, it might be the plundering of weapons or uniform insignia. Today, it is easier to just snap a photo that says: “My enemy is dead. I am alive. And I am very happy about that.”

But context matters. Often, a photo might not be telling the story it seems to. U.S. soldiers, for example, take photos of dead bodies all the time. But it’s not because they are debased gore junkies. It’s because they are ordered to. On the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan, soldiers are required to document not just every combat kill they are responsible for, but every dead body they happen upon, even if it is the product of local-on-local violence. Often they use their own cameras since the military-property cameras soldiers are supposed to use are frequently in short supply. They download the photos and send a selection of them to a lieutenant or captain who prepares a report (often a PowerPoint slide or deck known in the Army as a “storyboard”) for record keeping, archival and intelligence purposes and that officer then sends the report to higher headquarters.

That means a soldier may have a lot of photos of a lot of dead bodies on his hard drive almost by accident, frequently jumbled up with pictures of him horsing around with his friends in other times and locations, creating a photo flow that can be jarring to say the least. (The ease with which every soldier can take and send photos from anywhere in the world has its obvious benefits, but the drawbacks are extraordinary and, for government and military authorities, they are terrifying. Graphic, incendiary photos, whether official or unauthorized, can be duplicated and transmitted with a few keystrokes, and can spark an international incident of truly strategic importance in a matter of hours.)

If you are familiar with typical soldiers’ photo collections, here is a photo you see a lot: A dead Iraqi or Afghan sprawled on the top of a Humvee hood. Sounds barbaric, right? It looks barbaric. Ask the soldier about why he and his men treated the dead with such contempt, he will give you an unsentimental but practical answer: If you have to take a dead body back to base for identification or to return the corpse to the next of kin, there is frequently no room to transport the deceased any other way.

The act of taking photographs in such settings can go from morally neutral to disturbing in the blink of an eye. While documenting a completed battle’s death toll, what if a soldier’s buddy wanders into the frame? That’s okay, right? What if that buddy stops and looks into the camera lens—poses, you could say—next to a corpse? Hmmm, now we are treading into difficult territory. What if he then flashes a grin and pops a thumbs up? Clearly over the line, right? Yes. But it happens. It may not happen a lot, but it happens more than we would like to admit.

Jim Frederick is the Managing Editor of TIME.com and an Executive Editor of TIME magazine. He is the author of Black Hearts: One Platoon’s Descent Into Madness in Iraq’s Triangle of Death.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com