When astronomers try to explain why everyone should be as excited as they are about a bit of space news, they tend to reach for superlatives: This is the hottest/ coldest/ biggest/ smallest/ oldest/ most mysterious/ most powerful thing we’ve ever seen! So it’s no surprise that as they celebrated the first images to come back from Mercury, snapped by NASA’s Messenger probe, the first spacecraft ever to orbit this sun-scorched little world, mission scientists were at it again.

Mercury is the closest planet to the sun. It’s the smallest planet (now that Pluto doesn’t count, that is). It’s the densest. Its range of temperatures — from 950°F (510°C) on its sunlit side to -346°F (-210°C) on its shadowed side, thanks to the absence of any heat-distributing atmosphere — is almost unimaginable on a temperate world like ours, where the difference between the hottest and coldest parts of the planet rarely exceeds 100°F (55.55°C). At a NASA press conference Wednesday, March 30, lead scientist Sean Solomon, of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, sought to put an almost mythical gloss on things: This is the last of the classical planets, he said, the planets known to the astronomers of Egypt and Greece and Rome and the Far East — a bit of perspective that would thrill Latin and history teachers around the world.

If that were all there were to it, there might not be much of a story here. But if you care at all about planets, Mercury has all sorts of secrets that Aristotle never even thought to wonder about. Its great density is probably due to its relatively huge iron core, but it’s unclear how that core came about (one deliciously cataclysmic possibility: the lighter surface rocks were blasted away in a gigantic collision with another planet). The answer could come as Messenger studies the planet’s surface, and it could help theorists understand not just how Mercury came to be but how the entire solar system formed 4.5 billion years ago.

It’s also unclear whether the permanently shadowed regions near Mercury’s poles might be hiding deposits of ice. If there’s indeed ice present, it’s been there since the beginning of the planet’s life, and so it could also provide clues to the birth of the solar system.

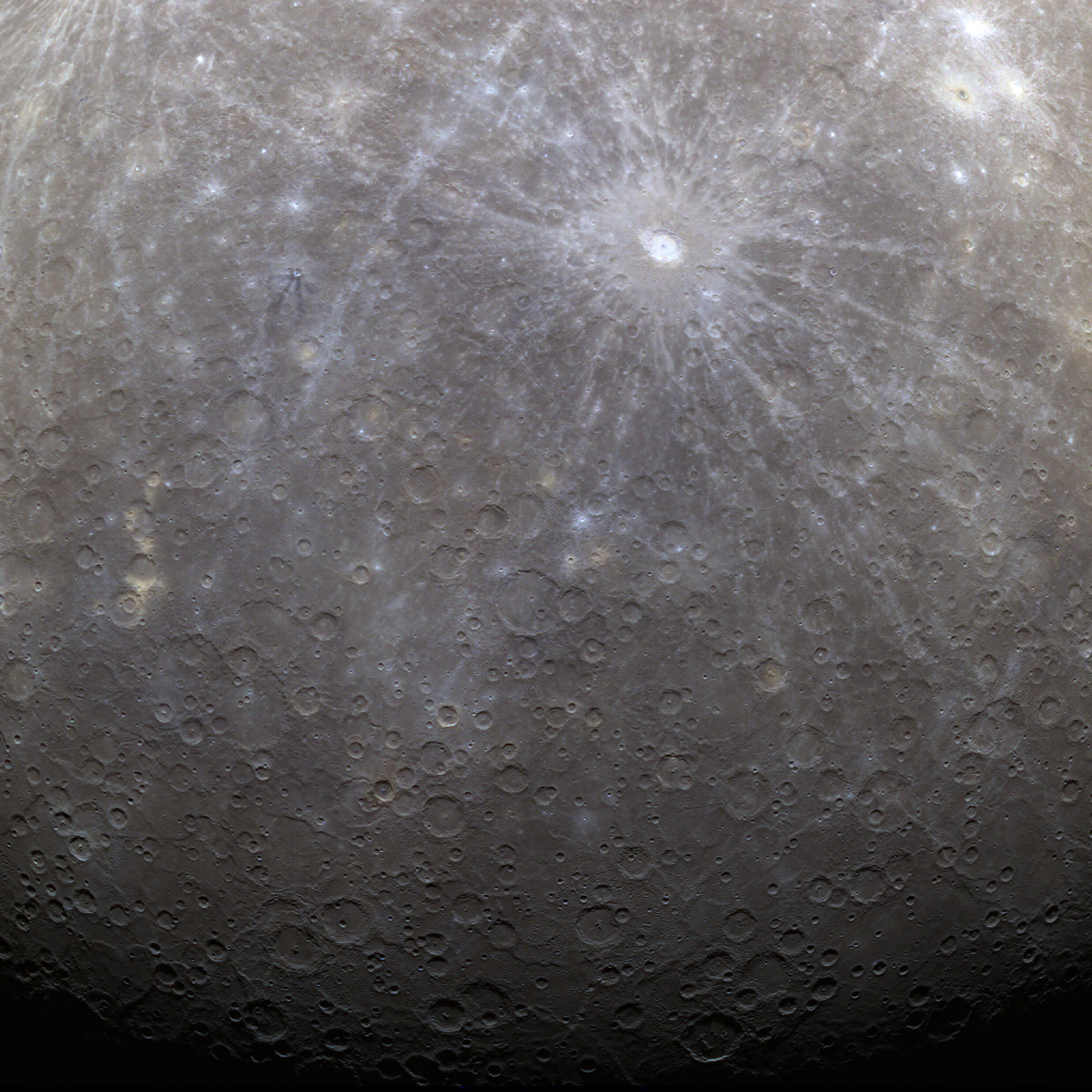

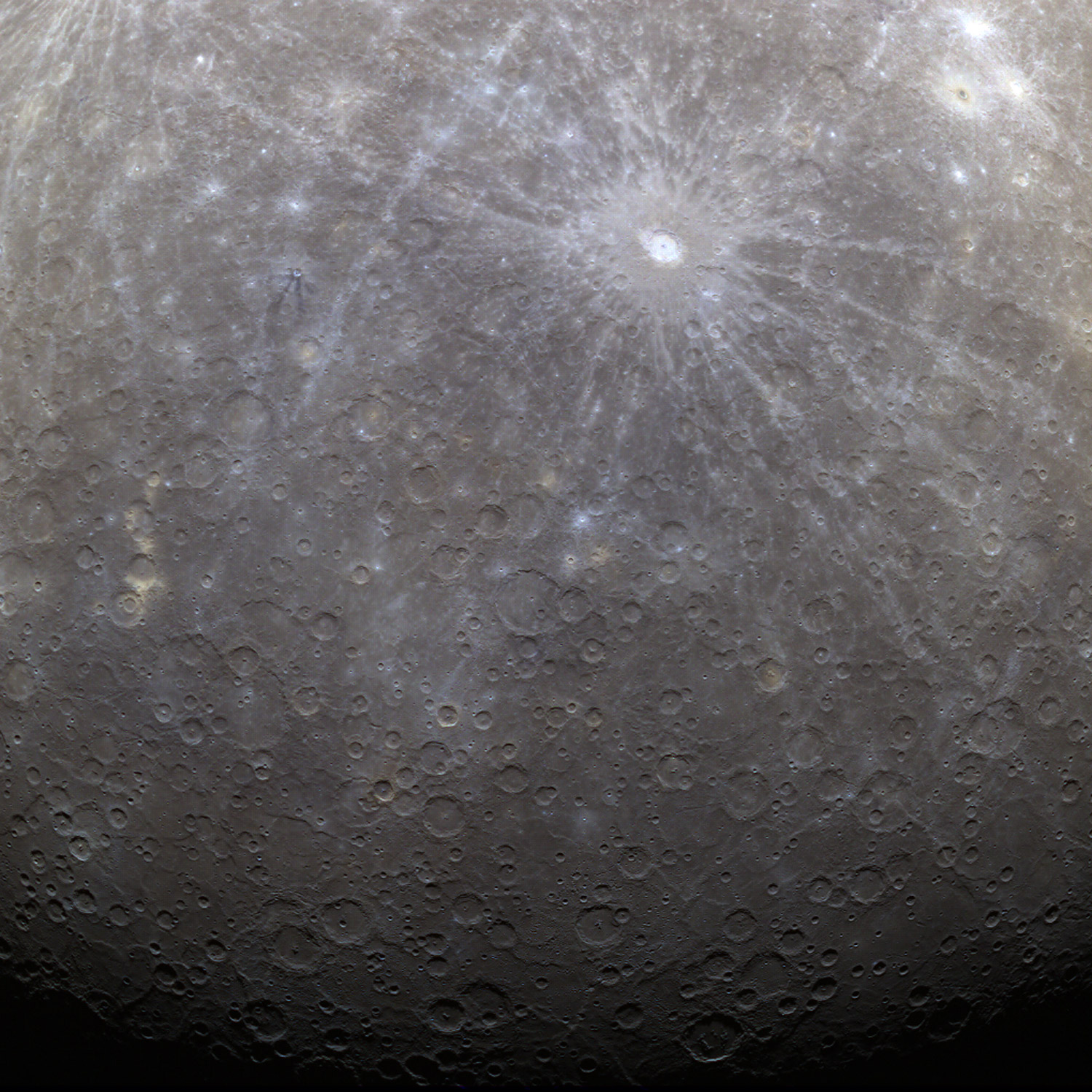

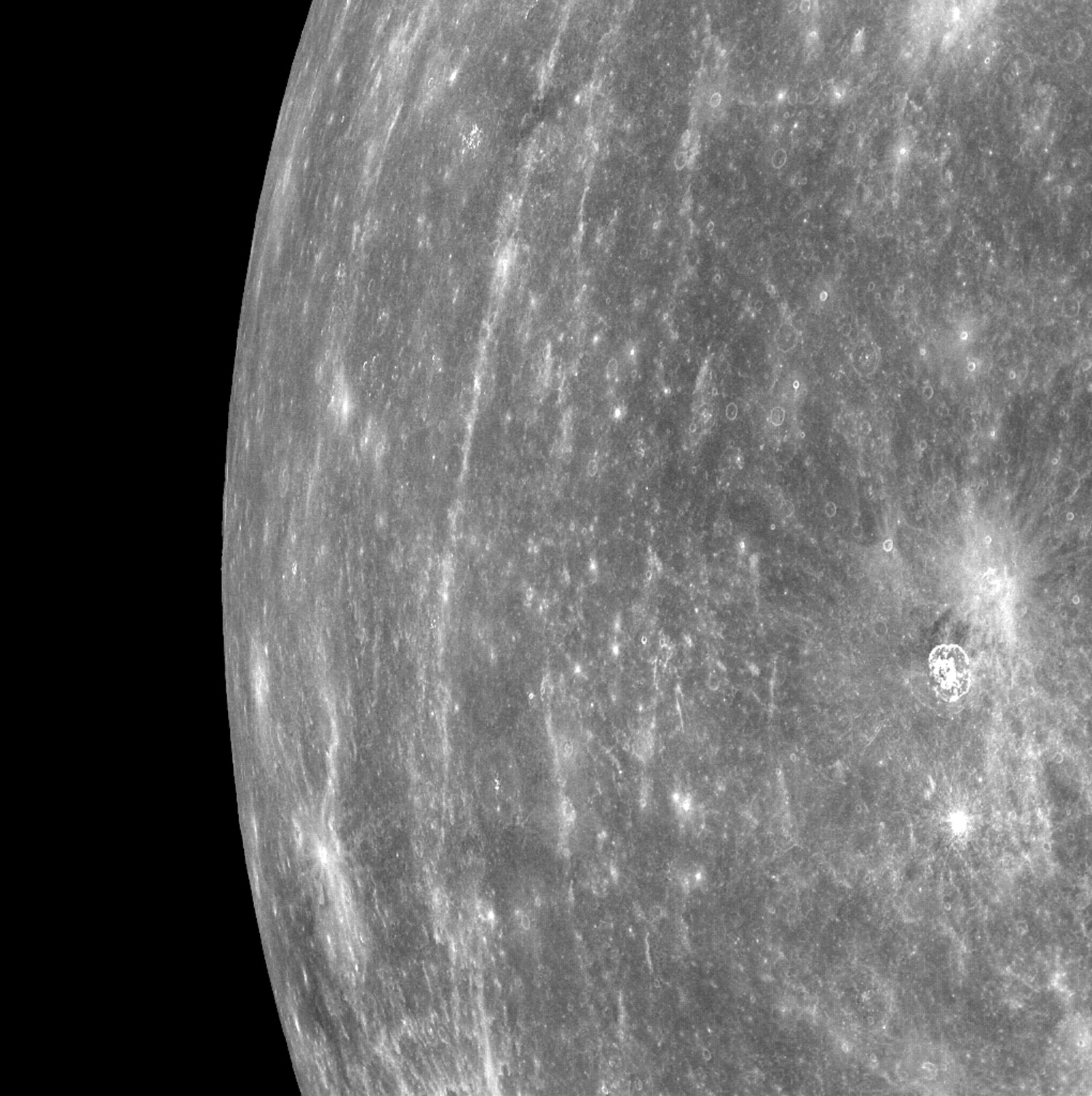

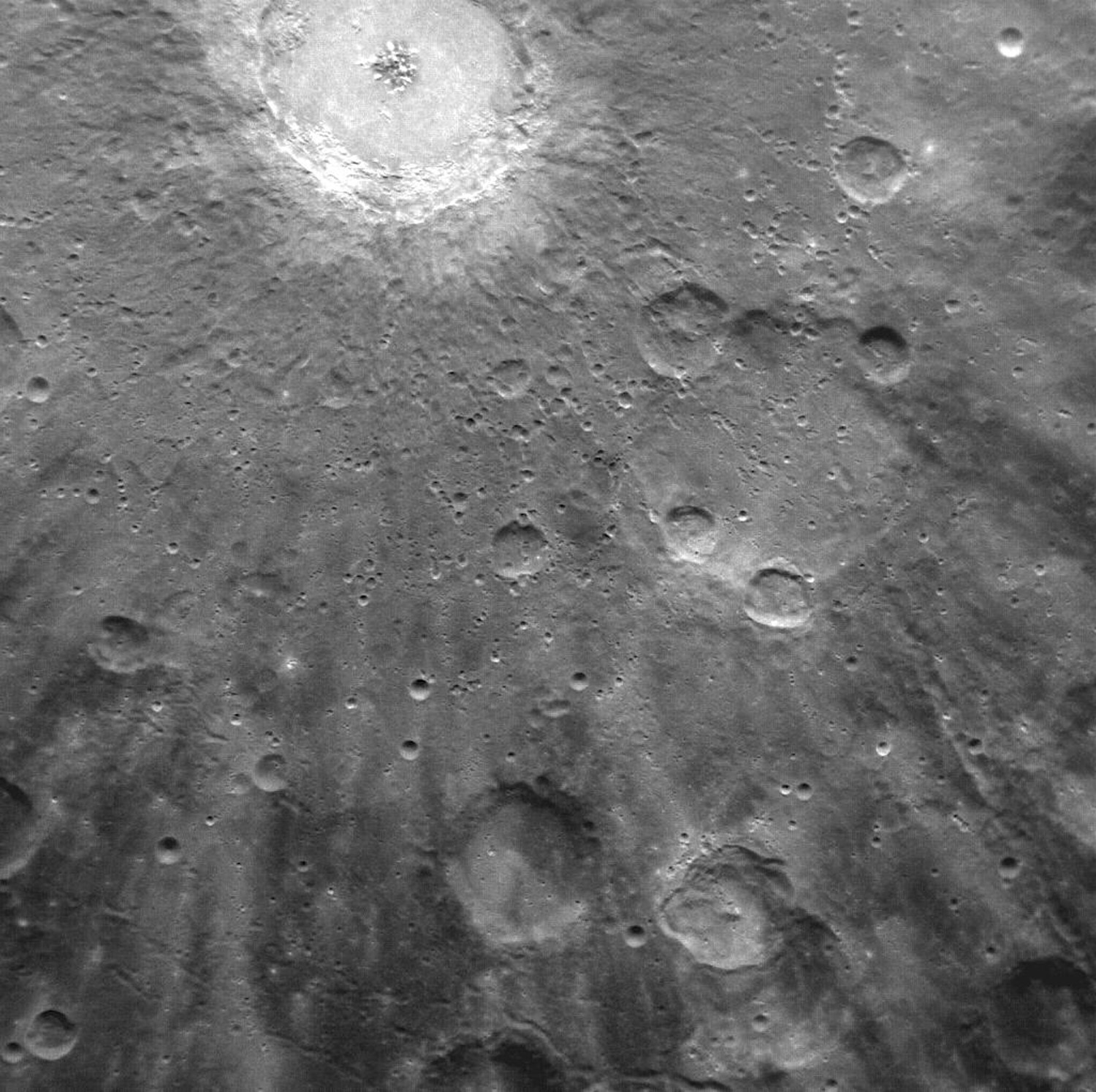

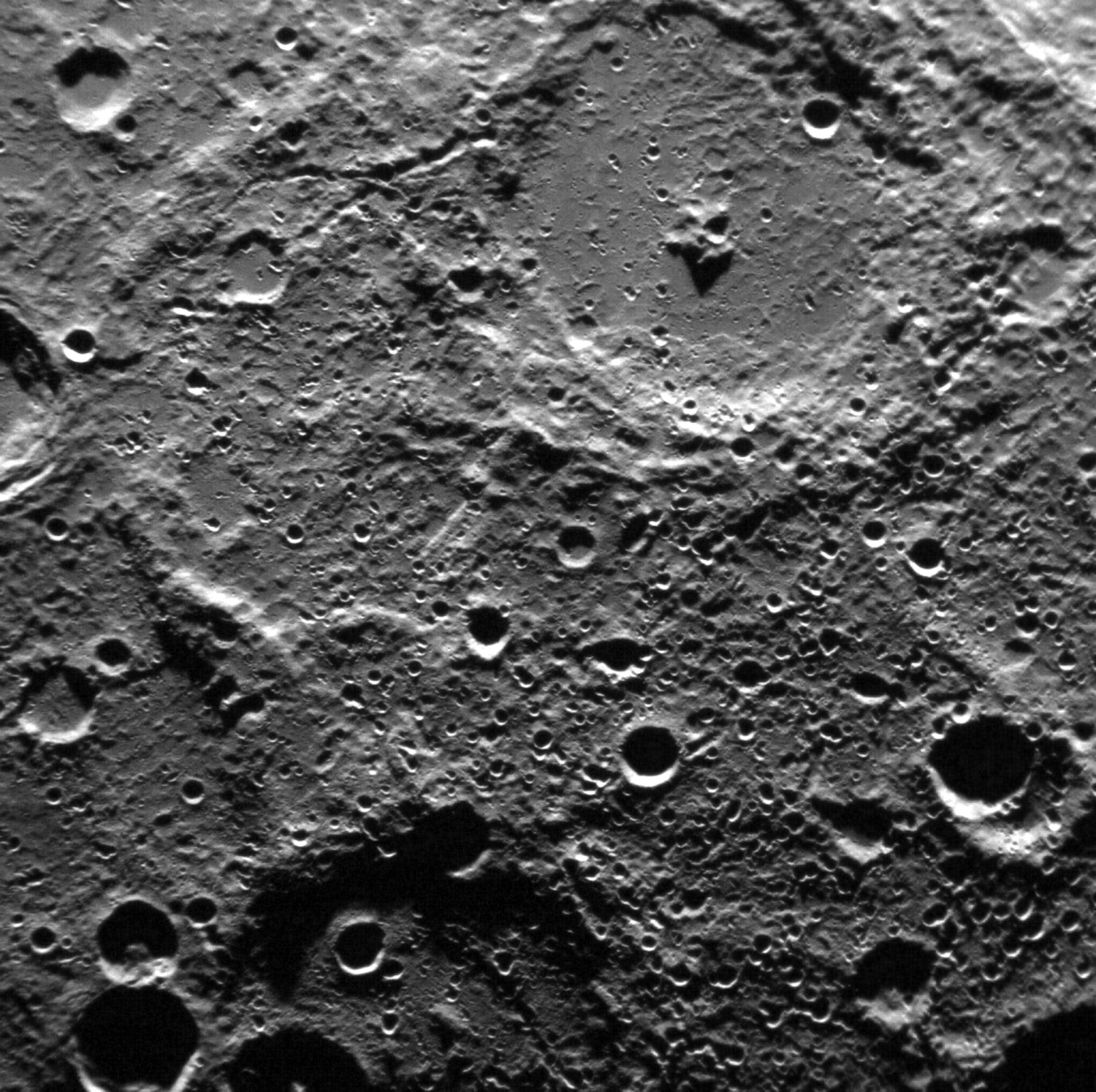

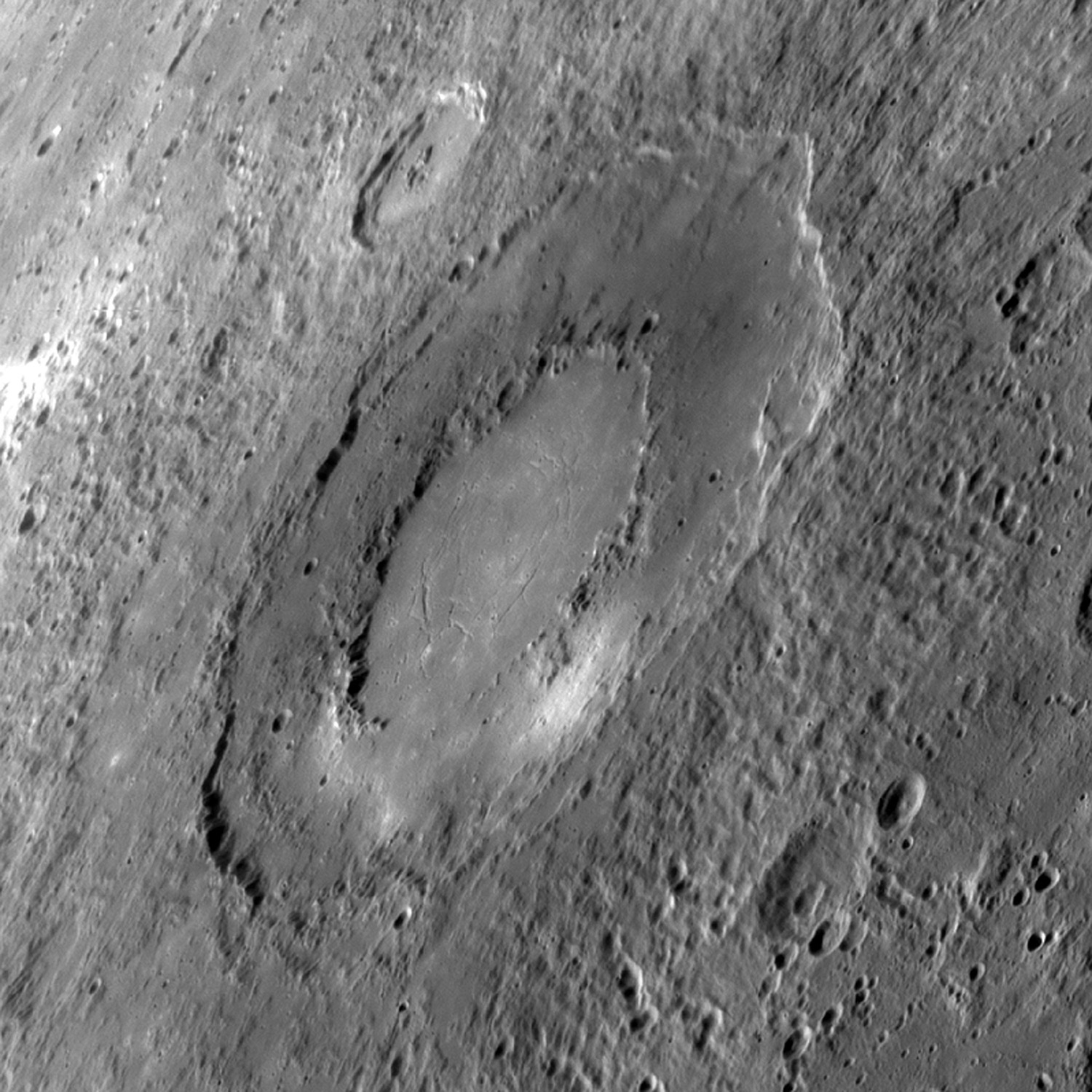

All the scientists can say for sure at this point has come from the photos Messenger began sending back March 30. The most striking thing they’ve confirmed so far is that Mercury is the most heavily cratered place they’ve ever seen — it makes the moon look as smooth as a parking lot. That’s because the moon has been at least partially resurfaced by huge lava flows; Mercury, by contrast, has had the same surface for many billions of years. Not only that: when an asteroid or meteorite slams into Mercury, the powerful gravity of the nearby sun means it’s going really fast.

Messenger’s full suite of neutron detectors and other instruments (there are seven in all) will kick in on Monday, April 4. The ship will then begin scrutinizing Mercury in unprecedented detail for at least the next year, whipping through a dizzying orbit that will take it from a high of 9,300 miles (15,000 km) to a low of 160 miles (257 km). As the ship goes about its work, many of Mercury’s most stubborn mysteries will at last begin to fall away.

Michael D. Lemonick spent nearly 21 years at TIME, where he wrote more than 50 cover stories on science, health and the environment. He is now senior writer at Climate Central, a nonprofit science and journalism organization. He is currently working on his fifth book, on the search for Earthlike planets around other stars.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com