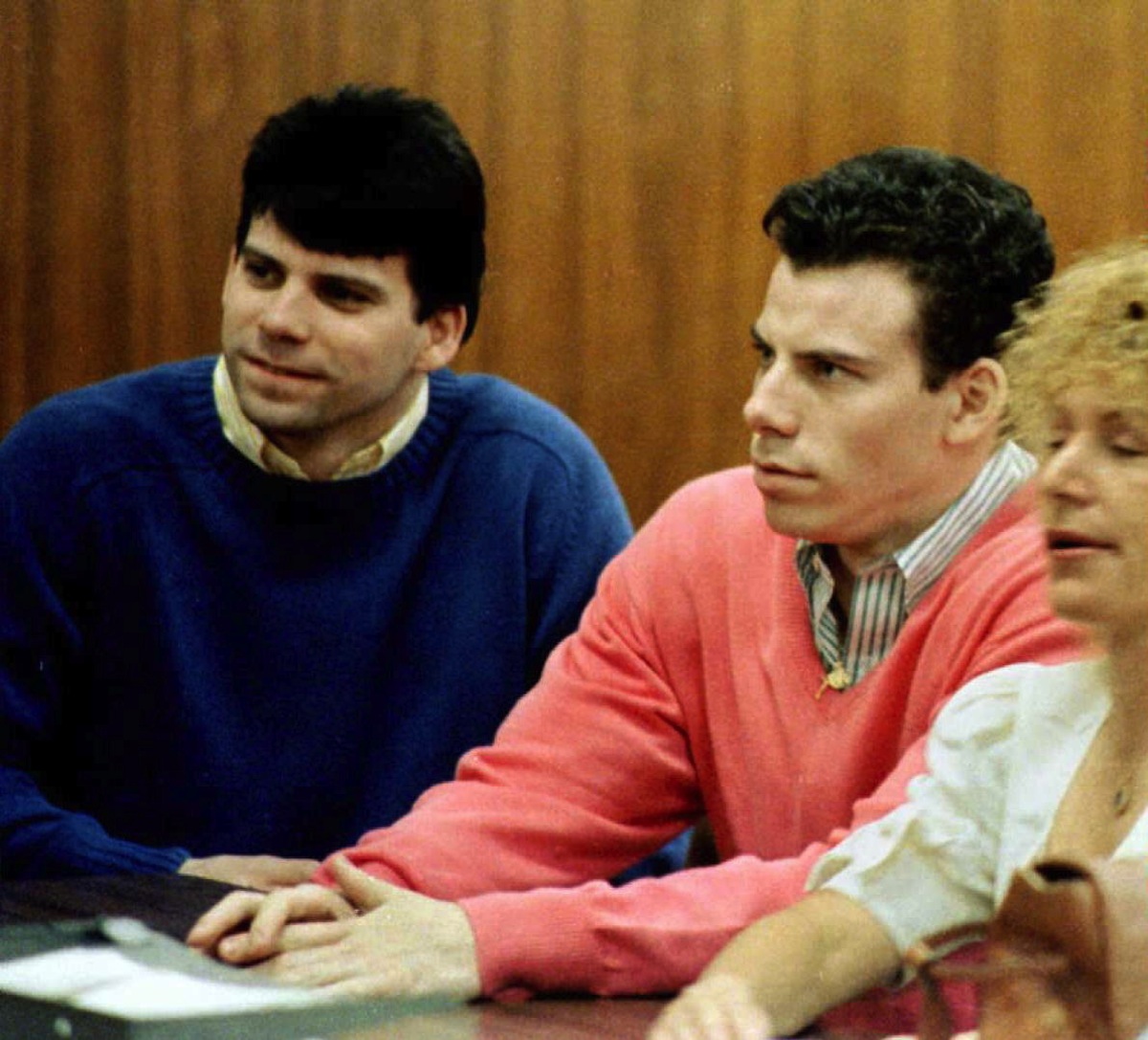

By the time of their trial, there was no question that Lyle and Erik Menendez had killed their parents. The question was why: specifically, whether greed alone had driven them to shoot their parents in cold blood. Defense attorneys countered this likelihood with an alternate motive — a lifetime of abuse — that two juries found at least somewhat compelling and a third did not. On this day, April 17, in 1996, the third and final jury recommended a life sentence for the Menendez brothers, without the possibility of parole.

The double murder had struck most people as especially cold, after all. Armed with shotguns, the brothers, then 18 and 21, had surprised Jose and Kitty Menendez while they sat watching TV and snacking on berries and cream in the family room of their Beverly Hills mansion, as TIME later reported. On that August night in 1989, the entertainment mogul and his wife were shot a total of 15 times.

While the murders were so violent and gruesome that police at first suspected a Mafia hit, attention quickly turned to the young men who stood to inherit $14 million — “ample motive for someone to kill somebody,” as the Beverly Hills district attorney told TIME in 1990.

It was hard not to notice the money trail that led from the crime scene — a $5 million estate that Elton John and Michael Jackson had each once called home — to the brothers, who spent as much as $700,000 of their inheritance in the months following the murders, according to Vanity Fair. Lyle alone spent $60,000 on a Porsche, $40,000 on clothing and $15,000 on a Rolex. Then he bought a restaurant in Princeton, near the campus where he had been a student until he was suspended for plagiarism in his freshman year.

Still, the case was not as open-and-shut as prosecutors had hoped. The defense argument that the brothers had been “punched, belt-whipped, and molested by their parents,” per TIME, was persuasive enough that the two juries who were assigned to the brothers (one jury per defendant) in their first trial wound up deadlocked over the possibility of self-defense.

“The jury looked shocked only twice: when Lyle’s cool voice came out of a boombox telling the therapist he would miss his dog as much as his parents, and when Erik said he felt love for his mother when he placed the shotgun in her cheek and blasted away her eye and nose,” TIME’s Margaret Carlson wrote. But over the course of a six-month trial, the defense chipped away at the jurors’ sense of horror and appealed to their empathy for two battered boys who could conceive no other way to escape their parents’ brutality.

The jury at their second trial was not as easily swayed.

“This time,” TIME summarized in 1996, “a single jury accepted the prosecution’s argument that the pair executed their mother and father in order to tap into the family fortune, rejecting the defense’s contention that the killings were a response to abuse.”

Read TIME’s 1993 take on the case, here in the archives: Sons and Murderers

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com