“And so today with my family by my side, I announce my candidacy for President of the United States.”

Over the next several weeks, at my last count, at least 17 Republican and Democrat candidates will say these words and begin running for our nation’s highest office. Kentucky Republican Sen. Rand Paul is expected to join that list today. But what happens before the banners are printed, the balloons drop, and the confetti falls?

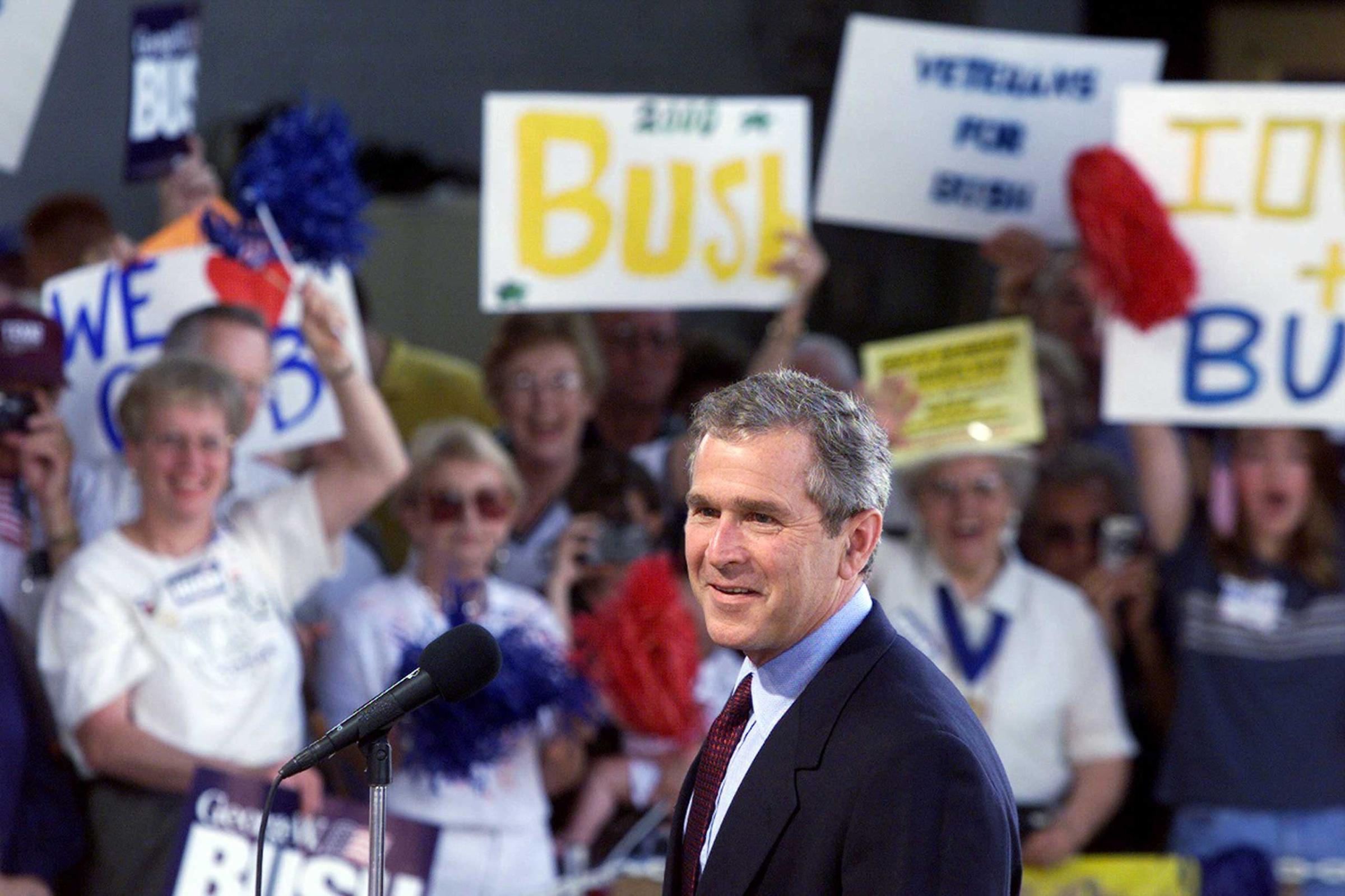

Up until now, these fledgling campaigns have been playing “off-Broadway,” engaging in what they call the invisible primary – the process of lining up donors and staff, road-testing messages, and building websites and databases, all in preparation for the big day. On announcement day, the previews are over, and the show is open to the public and the critics (the media). To prepare, the candidates and their teams will be trying to find that right mix of symbolism, message, and enthusiasm that will launch their drive to lead the free world.

When well executed, a good announcement helps set the tone for the campaign. It establishes the campaign’s message and tests the campaign’s organizational skills.

We remember Barack Obama announcing on a frigid day in Springfield, Illinois. Symbolism? I’m from the heartland, the land of Lincoln. Message? I am a historic figure as well – someone who can change the country. And nothing says enthusiasm like thousands of supporters standing in the bitter cold waiting for a candidate to speak.

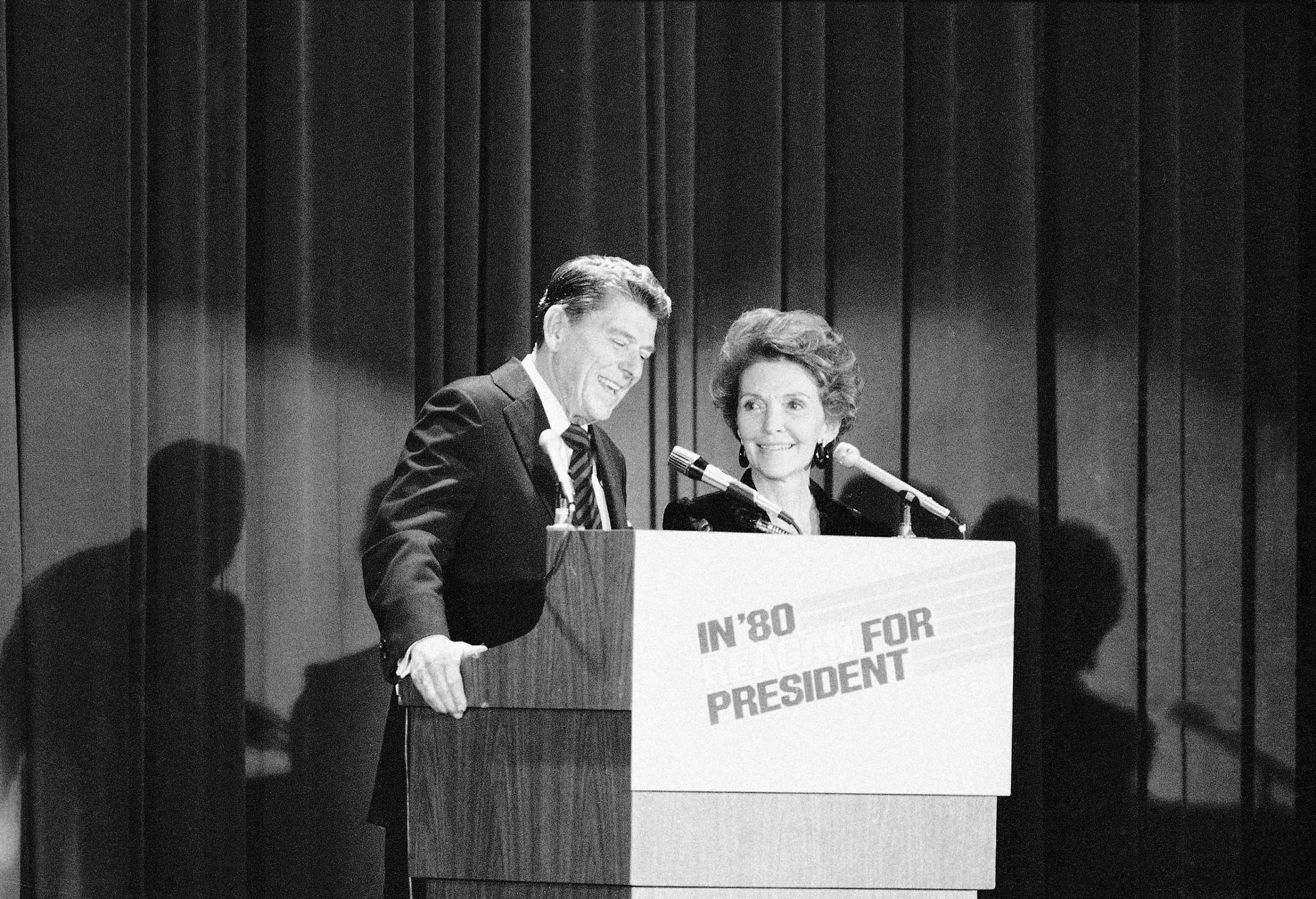

In June 2011, I imagine the Jon Huntsman campaign was riding pretty high when they pulled into Liberty State Park and announced the governor’s run for president. With the Statue of Liberty behind him, evoking memories of Ronald Reagan in 1980, Huntsman stepped forward to declare his candidacy. It all seemed like a good idea at the time. Yet, a series of mishaps, poor executions and the lack of an enthusiastic crowd drowned out Huntsman’s message. Instead, the campaign faced a week’s worth of negative stories about the process of announcing.

See 10 Presidential Campaign Launches

Sometimes fate or just bad luck intercedes. In 1995, I was working for Senator Robert Dole, and on the morning of his announcement, we were informed that the senator had a nasty, little, broken blood vessel in one eye. In person, it didn’t look that bad. But through a camera lens it appeared just awful. We had five campaign cameras filming the event plus thousands of media photographers getting the same tight shot of the senator with a red, bloodshot eye. And with Dole’s age already an issue, the crimson eye only fed reporters’ questions.

Then there is the campaign manager’s version of the 4 a.m. phone call. In the middle of the night before your announcement, you are informed of a natural disaster, terrorist attack, or that someone prominent has just died. This immediately forces the campaign to make a decision – cancel the announcement or stay the course and run the risk of appearing insensitive and having your big day lost to a bigger story. Lesson learned? If you are even discussing canceling the event, you probably should cancel the event.

Every four years it gets more difficult. The news cycles and the attention spans get shorter. Today the narrative is shaped not by operatives and journalists throwing back drinks at the end of the day, boys-on-the-bus style, but on Twitter, Snapchat, Meerkat, Facebook and a dozen other social media platforms where snark rules the day and judgments are passed in a 140 characters or fewer. It’s possible for a candidate’s announcement speech to be tried, judged, and a verdict reached even before the speech has ended.

So why even do it? There is nothing in the law that says you have to stage an announcement extravaganza. A candidate could tweet out that he or she is running for president, file the proper paperwork with the Federal Election Commission and go to lunch.

But the promise of the free media attention is way too tempting, and that pushes campaigns into devising all manner of announcement hoopla.

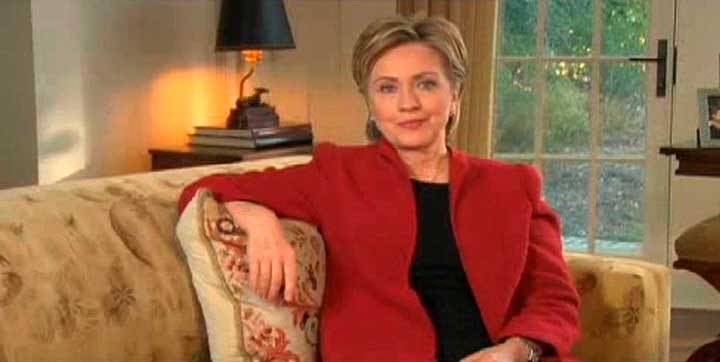

Whether a candidate announces in a field in New Hampshire, at a university in Virginia, or on the front porch of her girlhood home, for most of these candidates it will all end the same way — in a generic hotel suite on a night when not enough votes came their way with a hastily written concession speech in their pocket. And for the winner — well, their announcement won’t matter at all.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com