With the American Medical Association now urging doctors to treat obesity as a medical condition, physicians should be screening and treating overweight and obesity just as they would any other chronic disorder. But when it comes to figuring out which methods are proven to work best, physicians may find themselves at a loss. Some studies have found that commercial weight-loss programs work about the same when it comes to the amount of weight they can help consumers lose, while others found that low-carb diets beat out low-fat plans.

To make sense of the noise, Kimberly Gudzune, an assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, and her colleagues searched the scientific literature for studies on 11 commercial weight-loss programs. In their results, published Monday in the Annals of Internal Medicine, they assessed which ones have the best data to support them. But they also found there weren’t that many studies actually tracking how much weight people on the programs lose.

Gudzune decided to focus on commercial programs like Weight Watchers and NutriSystem, among others. And of 4,212 studies that involved these diets, only 45 were done under the gold scientific standard of randomly assigning people to a weight-loss program or not, and then tracking their weight changes over time. “The majority [of programs] still have no rigorous trials done,” says Gudzune.

According to her analysis, only two programs, Weight Watchers and Jenny Craig, helped dieters to lose weight and keep it off for at least a year. Those on Weight Watchers shed nearly 3% more of their starting weight after 12 months than those not dieting, and Jenny Craig users lost nearly 5%. Other programs, including Atkins, the Biggest Loser Club and eDiets, also helped people drop pounds, but since the studies only lasted three to six months, it’s impossible to know if that weight loss lasted.

The modest weight loss “may be disappointing to many consumers,” says Gudzune, but she notes that weight-management guidelines suggest that a 3% to 5% sustained weight loss is an important first step toward a healthy weight. “Even that small amount of weight loss can help to lower blood sugar, improve cholesterol profiles, help to lower blood pressure and ultimately prevent things like diabetes,” she says.

“Would 6% or 8% or 10% of body weight lost be better? Yes, but it’s not like the interaction is totally linear,” says Gary Foster, chief scientific officer of Weight Watchers International. Over time, weight-loss rates may change, and other studies show they typically slow after the initial blush of success.

Bananas

Why they’re good for you: While this tropical fruit is an American favorite, bananas are actually classified as an herb, and the correct name of a “bunch” of bananas is a “hand.” Technicalities aside, bananas are an excellent source of cardioprotective potassium. They’re an effective prebiotic, enhancing the body’s ability to absorb calcium, and they increase dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin – brain chemicals that counter depression.

Serving size: one medium banana

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 105

Fat: 0.4 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 1 mg

Carbohydrates: 27 g

Dietary fiber: 3 g

Sugars: 14 g

Protein: 1.3 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Citrusy Banana-Oat Smoothie

Ingredients

2/3 cup fresh orange juice

1/2 cup prepared quick-cooking oats

1/2 cup plain

2% reduced-fat Greek yogurt

1 tablespoon flaxseed meal

1 tablespoon honey

1/2 teaspoon grated orange rind

1 large banana, sliced and frozen

1 cup ice cubes

Preparation

Combine first 7 ingredients in a blender; pulse to combine. Add ice; process until smooth.

Raspberries

Why they’re good for you: Raspberries come in gold, black and purple varieties, but red are the most common. Research suggests eating raspberries may help prevent illness by inhibiting abnormal division of cells, and promoting normal healthy cell death. Raspberries are also a rich source of the flavonoids quercetin and gallic acid, which have been shown to boost heart health and prevent obesity and age-related decline.

Serving size: one cup of raspberries

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 64

Fat: 0.8 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 1 mg

Carbohydrates: 14.7 g

Dietary fiber: 8 g

Sugars: 5.4 g

Protein: 1.5 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Raspberry and Blue Cheese Salad

Ingredients

1 1/2 tablespoons olive oil

1 1/2 teaspoons red wine vinegar

1/4 teaspoon Dijon mustard

1/8 teaspoon salt

1/8 teaspoon pepper

5 cups mixed baby greens

1/2 cup raspberries

1/4 cup chopped toasted pecans

1 ounce blue cheese

Preparation

Combine olive oil, vinegar, Dijon mustard, salt, and pepper. Add mixed baby greens; toss. Top with raspberries, pecans, and blue cheese.

Oranges

Why they’re good for you: Oranges are one of the most potent vitamin C sources and are essential for disarming free-radicals, protecting cells, and sustaining a healthy immune system. Oranges contain a powerful flavonoid molecule called herperidin found in the white pith and peel. In animal studies, herperidin has been shown to lower cholesterol and high blood pressure. So don’t peel all the pith from your orange. Consider adding zest from the skin into your oatmeal for a dose of flavor and health.

Serving size: one large orange

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 86

Fat: 0.2 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 0 mg

Carbohydrates: 21.6 g

Dietary fiber: 4.4 g

Sugars: 17.2 g

Protein: 1.7 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Avocado and Orange Salad

Ingredients

1 tablespoon minced garlic

1 teaspoon olive oil

1/2 teaspoon black pepper

1/4 teaspoon kosher salt

1 orange

1/2 cup halved grape tomatoes

1/4 cup thinly sliced red onion

1 cup sliced avocado

Preparation

Combine garlic, olive oil, black pepper, and kosher salt in a medium bowl. Peel and section orange; squeeze membranes to extract juice into bowl. Stir garlic mixture with a whisk. Add orange sections, grape tomatoes, onion, and avocado to garlic mixture; toss gently.

Kiwi

Why they’re good for you: Ounce for ounce, this fuzzy fruit—technically a berry—has more vitamin C than an orange. It also contains vitamin E and an array of polyphenols, offering a high amount of antioxidant protection. Fiber, potassium, magnesium and zinc—partly responsible for healthy hair, skin and nails—are also wrapped up in this nutritious fruit.

Serving size: one kiwi

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 42

Fat: 0.4 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 2 mg

Carbohydrates: 10 g

Dietary fiber: 2 g

Sugars: 6 g

Protein: 0.8 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Shrimp and Kiwi Salad

Ingredients

1 tablespoon olive oil, divided

12 peeled and deveined large shrimp (about 3/4 pound)

1 tablespoon chopped green onions

1 tablespoon chopped fresh cilantro

1 tablespoon rice vinegar

1 tablespoon fresh lime juice

1 teaspoon grated lime rind

1/8 teaspoon salt

1/8 teaspoon crushed red pepper

1/8 teaspoon black pepper

2 cups torn red leaf lettuce leaves

1 cup cubed peeled kiwifruit (about 3 kiwifruit)

Preparation

Heat 1 teaspoon oil in a large nonstick skillet over medium-high heat. Add shrimp; sauté 4 minutes or until done. Remove from heat.

Combine 2 teaspoons oil, onions, and next 7 ingredients (onions through black pepper) in a bowl. Add shrimp; toss to coat. Spoon mixture over lettuce; top with kiwi.

Pomegranates

Why they’re good for you: Pomegranates tend to have more vitamin C and potassium and fewer calories than other fruits. A serving provides nearly 50% of a day’s worth of vitamin C and powerful polyphenols, which may help reduce cancer risk.

Serving size: one cup of pomegranate seeds

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 144

Fat: 2 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 5 mg

Carbohydrates: g

Dietary fiber: 7 g

Sugars: 23.8 g

Protein: 3 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Pomegranate and Pear Jam

Ingredients

2 cups sugar

2 cups chopped, peeled Seckel (or other) pear

2/3 cup strained fresh pomegranate juice (about 2 pomegranates)

1/4 cup rose wine

1/4 cup pomegranate seeds

1/2 teaspoon butter

2 tablespoons fruit pectin for less- or no-sugar recipes (such as Sure-Jell in pink box)

1 tablespoon grated lemon rind

1 teaspoon minced fresh rosemary

Preparation

Combine sugar, pear, pomegranate juice, and wine in a large saucepan over medium heat; stir until sugar melts. Bring to a simmer; simmer 25 minutes or until pear is tender. Remove from heat; mash with a potato masher. Add pomegranate seeds and butter; bring to a boil. Stir in fruit pectin. Return mixture to a boil; cook 1 minute, stirring constantly. Remove from heat; stir in lemon rind and rosemary. Cool to room temperature. Cover and chill overnight.

Blueberries

Why they’re good for you: Blueberries are rich in a natural plant chemical called anthocyanin which gives these berries their namesake color. Blueberries may help protect vision, lower blood sugar levels and keep the mind sharp by improving memory and cognition.

Serving size: one cup of blueberries

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 84

Fat: 0.5 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 1 mg

Carbohydrates: 21.5 g

Dietary fiber: 3.6 g

Sugars: 14.7 g

Protein: 1 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Lemon-Blueberry with Mascarpone Oatmeal

Ingredients

3/4 cup water

1/2 cup old-fashioned oats

Dash of salt

1 teaspoon sugar

1 tablespoon prepared lemon curd

3 tablespoons fresh blueberries

1 teaspoon mascarpone cheese

2 teaspoons sliced toasted almonds

Preparation

Bring water to a boil in a medium saucepan. Stir in oats and dash of salt. Reduce heat; simmer 5 minutes, stirring occasionally. Remove from heat, and stir in sugar and lemon curd. Top oatmeal with blueberries, mascarpone cheese, and almonds.

Grapefruit

Why it’s good for you: Grapefruit may not be heralded as a “superfruit,” but it should be. Available in white, pink, yellow and red varieties, grapefruit is low in calories and loaded with nutrients, supporting weight loss, clear skin, digestive balance, increased energy and heart and cancer prevention.

Serving size: one large grapefruit

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 53

Fat: 0.2 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 0 mg

Carbohydrates: 13.4 g

Dietary fiber: 1.8 g

Sugars: 11.6 g

Protein: 1 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Grilled Mahimahi with Peach and Pink Grapefruit Relish

Ingredients

1/3 cup rice vinegar

2 tablespoons brown sugar

1/2 cup finely chopped red onion

2 1/2 cups diced peeled ripe peaches (about 1 1/2 pounds)

1 1/2 cups pink grapefruit sections (about 2 large grapefruit)

1/2 cup small mint leaves

3/4 teaspoon salt, divided

1/2 teaspoon black pepper, divided

6 (6-ounce) mahimahi or other firm whitefish fillets (about 3/4 inch thick)

Preparation

Prepare grill.

Place vinegar and sugar in a small saucepan; bring to a boil. Remove from heat. Place onion in a large bowl. Pour vinegar mixture over onion, tossing to coat; cool. Add peaches, grapefruit, mint, 1/4 teaspoon salt, and 1/4 teaspoon pepper to onion; toss gently.

Sprinkle fish with 1/2 teaspoon salt and 1/4 teaspoon pepper. Place fish on grill rack coated with cooking spray; grill 5 minutes on each side or until fish flakes easily when tested with a fork.

Tangerines

Why they’re good for you: A tangerine has more antioxidants than an orange, and this powerful little fruit is full of soluble and insoluble fiber that play a role in reducing disease risk and supporting weight management. Tangerines are a good source of lutein and zeaxanthin, which help lower the risk of chronic eye diseases like cataracts and age-related macular degeneration. Animal studies have suggested that flavonoids found in tangerines may be protective against type 2 diabetes and heart disease, so use the zest on fruit and vegetables to reap the benefits of the fruit’s natural oils.

Serving size: one small tangerine

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 40

Fat: 0.2 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 2 mg

Carbohydrates: 10 g

Dietary fiber: 1.4 g

Sugars: 8 g

Protein: 0.6 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Tangerine and Avocado Salad with Pumpkin Seeds

Ingredients

2 tangerines, peeled

1 small avocado, peeled and sliced

1 tablespoon fresh lime juice

1 teaspoon extra-virgin olive oil

3 tablespoons toasted pumpkin seeds

1/4 teaspoon chili powder

Dash of kosher salt

Preparation

Cut tangerines into rounds. Combine tangerines, avocado, lime juice, and olive oil; toss gently to coat. Sprinkle with pumpkin seeds, chili powder, and a dash of kosher salt.

Avocado

Why it’s good for you: Avocados contain nearly 20 vitamins and minerals, many of which are easily absorbed by the body. Simply substituting one avocado for a source of saturated fat (such as butter or full fat cheese) may reduce your risk of heart disease, even without weight loss.

Serving size: one avocado

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 322

Fat: 29.5 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 14 mg

Carbohydrates: 17 g

Dietary fiber: 13.5 g

Sugars: 1 g

Protein: 4 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Chipotle Pork and Avocado Wrap

Ingredients

1/2 cup mashed peeled avocado

1 1/2 tablespoons low-fat mayonnaise

1 teaspoon fresh lime juice

2 teaspoons chopped canned chipotle chiles in adobo sauce

1/4 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon ground cumin

1/4 teaspoon dried oregano

4 (8-inch) fat-free flour tortillas

1 1/2 cups (1/4-inch-thick) slices cut Simply Roasted Pork (about 8 ounces)

1 cup shredded iceberg lettuce

1/4 cup bottled salsa

Preparation

Combine the first 7 ingredients, stirring well.

Warm tortillas according to package directions. Spread about 2 tablespoons avocado mixture over each tortilla, leaving a 1-inch border. Arrange Simply Roasted Pork slices down center of tortillas. Top each tortilla with 1/4 cup shredded lettuce and 1 tablespoon salsa, and roll up.

Tomatoes

Why they’re good for you: Tomatoes are a nutritional powerhouse. They’re rich in lycopene, a potent weapon against cancer. As one of the carotenoid phytochemicals (related to beta-carotene), lycopene appears to protect our cells’ DNA with its strong antioxidant power. Lycopene has also shown the ability to stimulate enzymes that deactivate carcinogens.

Serving size: one medium tomato

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 22

Fat: 0.25 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 6 mg

Carbohydrates: 4.8 g

Dietary fiber: 1.5 g

Sugars: 3.2 g

Protein: 1.1 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Tomato-Basil Soup

Ingredients

2 teaspoons olive oil

3 garlic cloves, minced

3 cups fat-free, less-sodium chicken broth

3/4 teaspoon salt

3 (14.5-ounce) cans no-salt-added diced tomatoes, undrained

2 cups fresh basil leaves, thinly sliced

Basil leaves (optional)

Preparation

Heat oil in a large saucepan over medium heat. Add garlic; cook 30 seconds, stirring constantly. Stir in the broth, salt, and tomatoes; bring to a boil. Reduce heat; simmer 20 minutes. Stir in basil.

Place half of the soup in a blender; process until smooth. Pour pureed soup into a bowl, and repeat procedure with remaining soup. Garnish with basil leaves, if desired.

Eggplant

Why it’s good for you: Deep-purple eggplant is classified as a nightshade vegetable, kin to the tomato and bell pepper. Purple foods can be a powerful weapon in fighting heart disease since they’re a rich source of phytonutrients—naturally occurring plant chemicals that have disease-protecting capabilities. One in particular, chlorogenic acid, is one of the most potent free radical scavengers found in plant tissues.

Serving size: one cup cooked eggplant

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 35

Fat: 0.2 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 1 mg

Carbohydrates: 8.6 g

Dietary fiber: 2.5 g

Sugars: 3 g

Protein: 0.8 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Barley Risotto with Eggplant and Tomatoes

Ingredients

6 cups (1/2-inch) diced eggplant

1 pint cherry tomatoes

3 tablespoons olive oil, divided

1/2 teaspoon black pepper, divided

5 cups fat-free, less-sodium chicken broth

2 cups water

1 1/2 cups finely chopped onion

1 cup uncooked pearl barley

2 teaspoons minced garlic

1/2 cup dry white wine

1/4 teaspoon salt

1/2 cup (2 ounces) crumbled soft goat cheese

1/4 cup thinly sliced fresh basil

1/4 cup pine nuts, toasted

Preparations

Preheat oven to 400°.

Combine eggplant, tomatoes, 2 tablespoons oil, and 1/4 teaspoon pepper in a bowl; toss to coat. Arrange mixture in a single layer on a jelly-roll pan. Bake at 400° for 20 minutes or until tomatoes begin to collapse and eggplant is tender.

Combine broth and 2 cups water in a medium saucepan; bring to a simmer (do not boil). Keep warm over low heat.

Heat remaining 1 tablespoon oil in a large nonstick skillet over medium-high heat. Add onion to pan; sauté 4 minutes or until onion begins to brown. Stir in barley and garlic; cook 1 minute. Add wine; cook 1 minute or until liquid almost evaporates, stirring constantly. Add 1 cup broth mixture to pan; bring to a boil, stirring frequently. Cook 5 minutes or until liquid is nearly absorbed, stirring constantly. Add remaining broth mixture, 1 cup at a time, stirring constantly until each portion of broth mixture is absorbed before adding the next (about 40 minutes total). Gently stir in eggplant mixture, remaining 1/4 teaspoon pepper, and salt. Top with cheese, basil, and nuts.

Swiss chard

Why it’s good for you: When it comes to nutrition, this is no lightweight. Swiss chard contains betalains (also found in beets), vitamins A, C , E and K, magnesium, potassium, fiber, calcium, choline, a host of B vitamins, zinc and selenium.

Serving size: one cup of raw swiss chard

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 7

Fat: 0.07 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 77 mg

Carbohydrates: 1.4 g

Dietary fiber: 0.6 g

Sugars: 0.4 g

Protein: 0.7 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Swiss Chard with Onions

Ingredients

2 teaspoons olive oil

2 cups thinly sliced onion

8 cups torn Swiss chard (about 12 ounces)

1 teaspoon Worcestershire sauce

1/4 teaspoon salt

1/8 teaspoon black pepper

Preparation

Heat oil in a large nonstick skillet over medium-high heat. Add onion; sauté 5 minutes or until lightly browned. Add chard; stir-fry 10 minutes or until wilted. Stir in Worcestershire, salt, and pepper.

Mushrooms

Why they’re good for you: Mushrooms are a rich source of ergothioneine, an antioxidant that may help fight cancer. Mushrooms are also a source of riboflavin, a vitamin that supports the body’s natural detoxification mechanisms. They are the highest vegan source of vitamin D.

Serving size: one cup of raw mushrooms

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 15

Fat: 0.2 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 4 mg

Carbohydrates: 2.3 g

Dietary fiber: 0.7 g

Sugars: 1.4 g

Protein: 2 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Penne with Sage and Mushrooms

Ingredients

1 whole garlic head

2 tablespoons plus 1 teaspoon olive oil

2 1/2 cups boiling water, divided

1/2 ounce dried wild mushroom blend (about 3/4 cup)

8 ounces uncooked 100 percent whole-grain penne pasta

1/4 cup fresh sage leaves

2 1/2 cups sliced cremini mushrooms (about 6 ounces)

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 cup fat-free, lower-sodium chicken broth

2 ounces fresh Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese, divided

Preparation

Preheat oven to 400°.

Cut top off garlic head. Place in a small baking dish, and drizzle with 1 teaspoon oil; cover with foil, and bake at 400° for 45 minutes. Remove dish from oven. Add 1/2 cup boiling water to dish; cover and let stand 30 minutes. Separate cloves; squeeze to extract garlic pulp into water. Discard skins. Mash garlic pulp mixture with a fork, and set aside.

Combine remaining 2 cups boiling water and dried mushrooms in a bowl; cover and let stand 30 minutes. Rinse mushrooms; drain well, and roughly chop. Set aside.

Cook pasta according to package directions, omitting salt and fat.

Heat remaining 2 tablespoons oil in a large nonstick skillet over medium-high heat. Add sage to pan; sauté 1 minute or until crisp and browned. Remove from pan using a slotted spoon; set aside. Add cremini mushrooms, salt, and pepper to pan; sauté 4 minutes. Add garlic mixture, chopped mushrooms, and broth to pan; cook 5 minutes or until liquid is reduced by about half. Grate 1 1/2 ounces cheese. Stir pasta and grated cheese into pan; cover and let stand 5 minutes. Thinly shave remaining 1/2 ounce cheese; top each serving evenly with cheese shavings and sage leaves.

Kale

Why it’s good for you: This dark green leafy vegetable is akin to Mother Nature’s sunglasses. Rich in the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin, kale delivers these pigments to the retina which absorb the sun’s damaging rays. Nutrients in kale have also been shown to lower cancer risk, support bone health and aid in natural detoxification.

Serving size: one cup of raw kale

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 8

Fat: 0.2 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 6 mg

Carbohydrates: 1 g

Dietary fiber: 0.6 g

Sugars: 0.4 g

Protein: 0.7 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Wilted Kale with Golden Shallots

Ingredients

2 tablespoons olive oil

2 sliced shallots

8 cups lacinato kale, stemmed and chopped

1/4 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon black pepper

2/3 cup unsalted chicken stock

Preparation

Heat a Dutch oven over medium heat. Add olive oil; swirl to coat. Add sliced shallots; cook 5 minutes or until golden, stirring frequently. Add kale, salt, and pepper to pan; cook 2 minutes. Add chicken stock; cover and cook 4 minutes or until tender, stirring occasionally.

Broccoli Sprouts

Why they’re good for you: Our skin, lungs, kidneys and liver are constantly detoxifying, but it’s nice to lend a helping hand. Eating broccoli sprouts, which look similar to alfalfa, may do just that. Rich in natural plant chemicals, broccoli sprouts may have cancer-fighting and antioxidant capabilities that help our cells protect us from disease.

Serving size: ½ cup

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 10

Fat: 0 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 0 mg

Carbohydrates: 1 g

Dietary fiber: 1 g

Sugars: 0 g

Protein: 1 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Seared Tofu with Gingered Vegetables and Broccoli Sprouts

Ingredients

1 cup broccoli sprouts

1 pound reduced-fat extra firm tofu

1 (3 1/2-ounce) bag boil-in-bag long-grain rice

3/4 teaspoon salt, divided

1 tablespoon dark sesame oil, divided

1 tablespoon bottled minced garlic

1 tablespoon bottled ground fresh ginger (such as Spice World)

1 large red bell pepper, thinly sliced

1 cup sliced green onions, divided

2 tablespoons rice vinegar

1 tablespoon low-sodium soy sauce

Cooking spray

1/4 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 tablespoon sesame seeds, toasted

Preparation

Place tofu on several layers of paper towels; let stand 10 minutes. Cut tofu into 1-inch cubes.

Prepare rice according to package directions, omitting salt and fat. Add 1/4 teaspoon salt to rice; fluff with a fork.

Heat 2 teaspoons oil in a large nonstick skillet over medium-high heat. Add garlic, ginger, and bell pepper to pan; sauté for 3 minutes. Stir in 3/4 cup onions, vinegar, and soy sauce; cook for 30 seconds. Remove from pan. Wipe skillet with paper towels; recoat pan with cooking spray.

Place pan over medium-high heat. Sprinkle tofu with remaining 1/2 teaspoon salt and black pepper. Add tofu to pan; cook 8 minutes or until golden, turning to brown on all sides. Return bell pepper mixture to pan, and cook 1 minute or until thoroughly heated. Drizzle tofu mixture with remaining 1 teaspoon oil; top with sesame seeds. Serve tofu mixture with rice; top with sprouts and remaining 1/4 cup onions.

Fennel

Why it’s good for you: Fennel is a vitamin cocktail, providing antioxidants, vitamin C, fiber, and a unique mix of phytonutrients. One such phytonutrient is called anethole which, in animal studies, has been shown to reduce inflammation and fend off chronic disease.

Serving size: one bulb of fennel

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 73

Fat: 0.5 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 122 mg

Carbohydrates: 17 g

Dietary fiber: g

Sugars: 9 g

Protein: 3 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Fennel Slaw with Orange Vinaigrette

Ingredients

1/4 cup extra-virgin olive oil

1 tablespoon sherry vinegar

1 teaspoon grated orange rind

1 1/2 tablespoons fresh orange juice

1 teaspoon kosher salt

1/4 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1/4 teaspoon crushed red pepper

3 medium fennel bulbs with stalks (about 4 pounds)

2 cups orange sections (about 2 large oranges)

1/2 cup coarsely chopped pitted green olives

Preparations

Combine the first 7 ingredients in a large bowl.

Trim tough outer leaves from fennel; mince feathery fronds to measure 1 cup. Remove and discard stalks. Cut fennel bulb in half lengthwise; discard core. Thinly slice bulbs. Add fronds, fennel slices, and orange sections to bowl; toss gently to combine. Sprinkle with olives.

Garlic

Why it’s good for you: This pungent little allium has serious health merits, packing both flavonoids and sulfur-containing nutrients that bolster immunity and support healthy joints. It’s well-known for its cardioprotective benefits, and garlic is also an effective antiviral.

Serving size: one clove

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 4

Fat: 0.02 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 1 mg

Carbohydrates: 1 g

Dietary fiber: 0.1 g

Sugars: 0.03 g

Protein: 0.2 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Garlic-and-Herb Oven-Fried Halibut

Ingredients

1 cup panko (Japanese breadcrumbs)

1 tablespoon chopped fresh basil

1 tablespoon chopped fresh flat-leaf parsley

1/2 teaspoon onion powder

1 large garlic clove, minced

2 large egg whites, lightly beaten

1 large egg, lightly beaten

2 tablespoons all-purpose flour

6 (6-ounce) halibut fillets

3/4 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon black pepper

2 tablespoons olive oil, divided

Cooking spray

Preparation

Preheat oven to 450°.

Combine first 5 ingredients in a shallow dish. Place egg whites and egg in a shallow dish. Place flour in a shallow dish. Sprinkle fish with salt and pepper. Dredge fish in flour. Dip in egg mixture; dredge in panko mixture.

Heat 1 tablespoon oil in a large nonstick skillet over medium-high heat. Add 3 fish fillets; cook 2 1/2 minutes on each side or until browned. Place fish on a broiler pan coated with cooking spray. Repeat procedure with remaining 1 tablespoon oil and remaining fish. Bake at 450° for 6 minutes or until fish flakes easily when tested with a fork or until desired degree of doneness.

Sweet potatoes

Why they’re good for you: Even though sweet potatoes have a bit more natural sugar than white potatoes, they are a mighty orange package of nutrients. A large sweet potato contains more than a day’s worth of vitamin A, essential for eyesight and reproductive health. It also has B vitamins, fiber and potassium and an antioxidant called glutathione, which may enhance immunity and supports metabolism.

Serving size: one medium cooked sweet potato

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 103

Fat: 0.2 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 41 mg

Carbohydrates: 23.7 g

Dietary fiber: 3.8 g

Sugars: 7.4 g

Protein: 2.3 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Spicy Grilled Sweet Potatoes

Ingredients

3/4 teaspoon ground cumin

1/2 teaspoon garlic powder

1/4 teaspoon salt

1/8 teaspoon ground red pepper

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 pound peeled sweet potatoes, cut into 1/4-inch-thick slices

Cooking spray

2 tablespoons chopped fresh cilantro

Preparation

Combine the first 4 ingredients in a small bowl.

Combine oil and sweet potatoes in a medium bowl; toss to coat. Heat a large grill pan coated with cooking spray over medium heat. Add potatoes, and cook for 10 minutes, turning occasionally. Place potatoes in a large bowl; sprinkle with cumin mixture and cilantro. Toss gently.

Beets

Why they’re good for you: It’s hard to beat beets. Research shows they’re a good source of antioxidants and have compounds that can help lower blood pressure and LDL cholesterol. They also look lovely on your plate thanks to betalains—the pigment that gives them their color. Betalains are destroyed by heat, so steam beets or roast them for less than an hour to derive maximum nutrition benefits.

Serving size: one cup of cooked beets

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 37

Fat: 0.2 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 65 mg

Carbohydrates: 8.5 g

Dietary fiber: 2 g

Sugars: 7 g

Protein: 1.4 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Roasted Beet and Shallot Salad over Wilted Beet Greens and Arugula

Ingredients

1 1/2 pounds beets

8 shallots, peeled and halved

Cooking spray

1 tablespoon balsamic vinegar

1 teaspoon grated orange rind

2 teaspoons olive oil, divided

1/2 teaspoon salt, divided

1 teaspoon sugar

2 teaspoons cider vinegar

5 cups trimmed arugula (about 5 ounces)

2 tablespoons chopped walnuts, toasted

Preparation

Preheat oven to 425°.

Trim beets, reserving greens. Wrap beets in foil. Place beets and shallots on a baking sheet coated with cooking spray. Coat shallots with cooking spray. Bake at 425° for 25 minutes or until shallots are lightly browned. Remove shallots from pan. Return beets to oven; bake an additional 35 minutes or until beets are tender. Cool. Peel beets; cut into 1/2-inch wedges. Place beets, shallots, vinegar, rind, 1 teaspoon oil, and 1/4 teaspoon salt in a large bowl; toss well.

Heat remaining 1 teaspoon oil in a large nonstick skillet over medium-high heat. Add reserved beet greens to pan; sauté 1 minute or until greens begin to wilt. Stir in sugar, cider, and remaining 1/4 teaspoon salt; cook 30 seconds, stirring constantly. Remove pan from heat. Add arugula; stir just until wilted. Place about 1 cup greens mixture on each of 4 plates. Sprinkle each serving with 1 1/2 teaspoons walnuts; top each serving with 3/4 cup beet mixture.

Spinach

Why it’s good for you: Spinach is among the top greens for folate, and contains high amounts of vitamin A, iron, potassium, calcium, zinc and selenium which offers antioxidant protection and supports thyroid function.

Serving size: one cup of raw spinach

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 7

Fat: 0.4 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 24 mg

Carbohydrates: 1 g

Dietary fiber: 0.7 g

Sugars: 0.1 g

Protein: 1 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Spinach-and-Grapefruit Salad

Ingredients

2 tablespoons chopped pecans

8 cups torn spinach

2 cups red grapefruit sections (about 3 medium grapefruit)

2 cups sliced mushrooms (about 8 ounces)

1/4 cup (1 ounce) crumbled blue cheese

1/2 cup raspberry fat-free vinaigrette (such as Girard’s)

Preparation

Place the pecans in a large skillet, and cook over medium heat 3 minutes or until lightly browned, shaking skillet frequently. Set aside.

Place 2 cups spinach on each of 4 serving plates. Arrange 1/2 cup grapefruit and 1/2 cup mushrooms over spinach. Sprinkle each serving with 1 tablespoon cheese and 1 1/2 teaspoons pecans; drizzle each with 2 tablespoons vinaigrette.

Cauliflower

Why it’s good for you: Cauliflower, which is found in white, purple, green and orange varieties, is a cancer-fighting powerhouse and supports our body’s natural detoxification process. It’s rich in an assortment of phytonutrients that reduce oxidative stress in our cells. Interestingly, research has shown that cauliflower combined with turmeric have have potential in preventing and treating prostate cancer.

Serving size: one cup of chopped raw cauliflower

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 27

Fat: 0.3 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 32 mg

Carbohydrates: g

Dietary fiber: 2 g

Sugars: 2 g

Protein: 2 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Roasted Cauliflower

Ingredients

2 teaspoons olive oil

2 medium onions, quartered

5 garlic cloves, halved

4 cups cauliflower florets (about 1 1/2 pounds)

Cooking spray

1 tablespoon water

1 tablespoon Dijon mustard

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 tablespoon chopped fresh flat-leaf parsley

Preparation

Preheat oven to 500°.

Heat oil in a large skillet over medium heat. Add onions and garlic; cook 5 minutes or until browned, stirring frequently. Remove from heat.

Place onion mixture and cauliflower in a roasting pan coated with cooking spray. Combine water and mustard; pour over vegetable mixture. Toss to coat; sprinkle with salt and pepper. Bake at 500° for 20 minutes or until golden brown, stirring occasionally. Sprinkle with parsley.

Collard greens

Why they’re good for you: A sister to broccoli and Brussels sprouts, collards are considered a cruciferous vegetable. Cooked collards are effective at lowering cholesterol—more so than even kale—as well as fighting cancer. Just one-half cup of collard greens contains two-days’ worth of vitamin A, essential for healthy vision, teeth and skin.

Serving size: one cup cooked collard greens

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 63

Fat: 1.4 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 28 mg

Carbohydrates: 10.7 g

Dietary fiber: 7.6 g

Sugars: 0.8 g

Protein: 5.2 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Stewed Collards

Ingredients

Cooking spray

1 cup vertically sliced onion

8 cups chopped collard greens

2 cups unsalted chicken stock

1 teaspoon sugar

1/4 teaspoon salt

2 teaspoons cider vinegar

Preparation

Heat a Dutch oven over medium-high heat. Coat pan with cooking spray. Add onion; sauté 3 minutes. Add collard greens, chicken stock, sugar, and salt. Cover; bring to a boil. Reduce heat to low; simmer 20 minutes or until very tender. Stir in vinegar.

Onions

Why they’re good for you: Alliums like onions are rich in healthy, sulfur-containing compounds which are also responsible for their pungent smell. Onions are good sources of vitamins C and B6, manganese, potassium and fiber. They’re also a superb source of the antioxidant quercetin. While research is inconclusive, quercetin is suspected of supporting heart health, combating inflammation and reducing allergy symptoms.

Serving size: one cup of cooked onions

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 92

Fat: 0.4 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 3 mg

Carbohydrates: 21 g

Dietary fiber: 3 g

Sugars: 10 g

Protein: 3 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Patty Melts with Grilled Onions

Ingredients

8 (1/8-inch-thick) slices Vidalia or other sweet onion

1 tablespoon balsamic vinegar

Cooking spray

1 pound extra-lean ground beef

1/4 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

3 tablespoons creamy mustard blend (such as Dijonnaise)

8 (1-ounce) slices rye bread

1 cup (4 ounces) shredded reduced-fat Jarlsberg cheese

Preparation

Arrange onion slices on a plate. Drizzle vinegar over onion slices. Heat a large grill pan over medium heat. Coat pan with cooking spray. Add onion to pan; cover and cook 3 minutes on each side. Remove from pan; cover and keep warm.

Heat pan over medium-high heat. Coat pan with cooking spray. Divide beef into 4 equal portions, shaping each into a 1/2-inch-thick patty. Sprinkle patties evenly with salt and pepper. Add patties to pan; cook 3 minutes on each side or until done.

Spread about 1 teaspoon mustard blend over 4 bread slices; layer each slice with 2 tablespoons cheese, 1 patty, 2 onion slices, and 2 tablespoons cheese. Spread about 1 teaspoon mustard blend over remaining bread slices; place, mustard side down, on top of sandwiches.

Heat pan over medium heat. Coat pan with cooking spray. Add sandwiches to pan. Place a cast-iron or other heavy skillet on top of sandwiches; press gently to flatten. Cook 3 minutes on each side or until bread is toasted (leave cast-iron skillet on sandwiches while they cook).

Winter Squash

Why it’s good for you: Winter squash is an inexpensive vegetable that’s as healthy as it is versatile. It’s one of the richest sources of plant-based anti-inflammatory beta-carotene, which can support healthy vision and cell development. Its yellow-orange flesh is also infection protective, and may even reduce age-associated illnesses.

Serving size: one cup of cooked winter squash

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 180

Fat: 0.2 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 8 mg

Carbohydrates: g

Dietary fiber: 6.6 g

Sugars: 4 g

Protein: 1.8 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Pasta with Winter Squash and Pine Nuts

Ingredients

2 tablespoons butter

2 tablespoons pine nuts, toasted

1 tablespoon chopped fresh sage

1 teaspoon olive oil

1 garlic clove, minced

2 1/2 cups water, divided

1 pound butternut squash, peeled, seeded, and shredded

1 teaspoon sugar

3/4 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon black pepper

12 ounces uncooked penne (tube-shaped pasta)

1 cup (4 ounces) finely shredded Parmesan cheese, divided

Preparation

Melt 2 tablespoons butter in a large nonstick skillet over medium-high heat until lightly browned. Add pine nuts and sage; remove from heat. Remove from pan, and set aside.

Heat olive oil in pan over medium-high heat. Add garlic to pan, and sauté 30 seconds. Reduce heat to medium. Add 1 cup water and squash to pan. Cook for 12 minutes or until water is absorbed, stirring occasionally. Add remaining water, 1/2 cup at a time, stirring occasionally until each portion of water is absorbed before adding the next (about 15 minutes). Stir in sugar, salt, and pepper.

Cook pasta according to package directions, omitting salt and fat. Drain, reserving 1/2 cup pasta water. Combine pasta and squash mixture in a large bowl. Add reserved 1/2 cup pasta water, butter mixture, and 3/4 cup cheese; toss well. Sprinkle with remaining 1/4 cup cheese. Serve immediately.

Tuna

Why it’s good for you: Experts recommend the general population, as well as pregnant and breastfeeding women, eat 8 to 12 ounces of seafood weekly to boost brain health and avoid the risk of developing cardiovascular disease. Choosing fish rich in essential Omega-3 fatty acids like tuna–and even canned tuna–can promote immunity, heart health and may even lessen postpartum depression. Don’t go overboard, though—tuna can be high in mercury.

Serving size: 3 oz.

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 93

Fat: 0.4 g

Cholesterol: 33 mg

Sodium: 38 mg

Carbohydrates: 0 g

Dietary fiber: 0 g

Sugars: 0 g

Protein: 20.7 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Arugula, Italian Tuna, and White Bean Salad

Ingredients

3 tablespoons fresh lemon juice

1 1/2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1/2 teaspoon minced garlic

1/4 teaspoon kosher salt

1/4 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1/4 teaspoon Dijon mustard

1 cup grape tomatoes, halved

1 cup thinly vertically sliced red onion

2 (6-ounce) cans Italian tuna packed in olive oil, drained and broken into chunks$

1 (15-ounce) can cannellini beans, rinsed and drained

1 (5-ounce) package fresh baby arugula

2 ounces Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese, shaved

Preparation

Whisk together first 6 ingredients in a large bowl. Add tomatoes and next 4 ingredients (through arugula); toss. Top with cheese.

Sardines

Why they’re good for you: Sardines are tiny but mighty, rivaling salmon when it comes to omega-3 fatty acid content. These fatty acids go to work immediately (as opposed to plant-based omega 3s), improving blood flow, feeding our brain, stabilizing heart rhythms and keeping inflammation in check. Sardines are also a source of calcium. Look for the varieties packed in olive oil for an added heart-health benefit.

Serving size: one can

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 191

Fat: 10.5 g

Cholesterol: 131 mg

Sodium: 282 mg

Carbohydrates: 0 g

Dietary fiber: 0 g

Sugars: 0 g

Protein: 22.7 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Fennel-Sardine Spaghetti

Ingredients

8 ounces uncooked spaghetti

1 medium fennel bulb (about 8 ounces)

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 cup prechopped onion

3 garlic cloves, chopped

1 cup tomato sauce

1 teaspoon dried oregano

1/8 teaspoon crushed red pepper

1 (15-ounce) can sardines in tomato sauce, undrained

Preparation

Cook pasta according to package directions; drain.

Trim outer leaves from fennel. Chop fronds to measure 1/2 cup. Discard stalks. Cut bulb in half lengthwise; discard core. Thinly slice bulb.

Heat oil in a large skillet over medium-high heat. Add sliced fennel and onion; sauté 4 minutes. Add garlic; sauté 20 seconds. Stir in tomato sauce, oregano, red pepper, and sauce from sardines. Cover and reduce heat.

Discard backbones from fish. Add fish to pan; gently break fish into chunks. Cover and cook 6 minutes. Toss pasta with sauce; sprinkle with fronds.

Anchovies

Why they’re good for you: This bite-sized fish shows up in many signature dishes from Italy, Thailand, Spain and Korea. Just three ounces of Anchovies offer 19 grams of protein, as well as B vitamins, calcium, iron and omega-three fatty acids. They’re also low in mercury.

Serving size: five anchovies from a can

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 42

Fat: 2 g

Cholesterol: 38 mg

Sodium: 734 mg

Carbohydrates: 0 g

Dietary fiber: 0 g

Sugars: 0 g

Protein: 5.8 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Spicy Anchovy Broccoli

Ingredients

2 tablespoons canola oil

2 teaspoons chopped fresh thyme

2 teaspoons grated lemon rind

3/4 teaspoon crushed red pepper

1/4 teaspoon kosher salt

3 garlic cloves, minced

2 drained and minced anchovy fillets

4 cups broccoli florets, steamed

Preparation

Heat canola oil, thyme, lemon rind, crushed red pepper, kosher salt, minced garlic, and minced anchovy fillets in a small skillet over medium heat; cook 2 minutes or until garlic begins to sizzle. Add steamed broccoli florets; toss to coat.

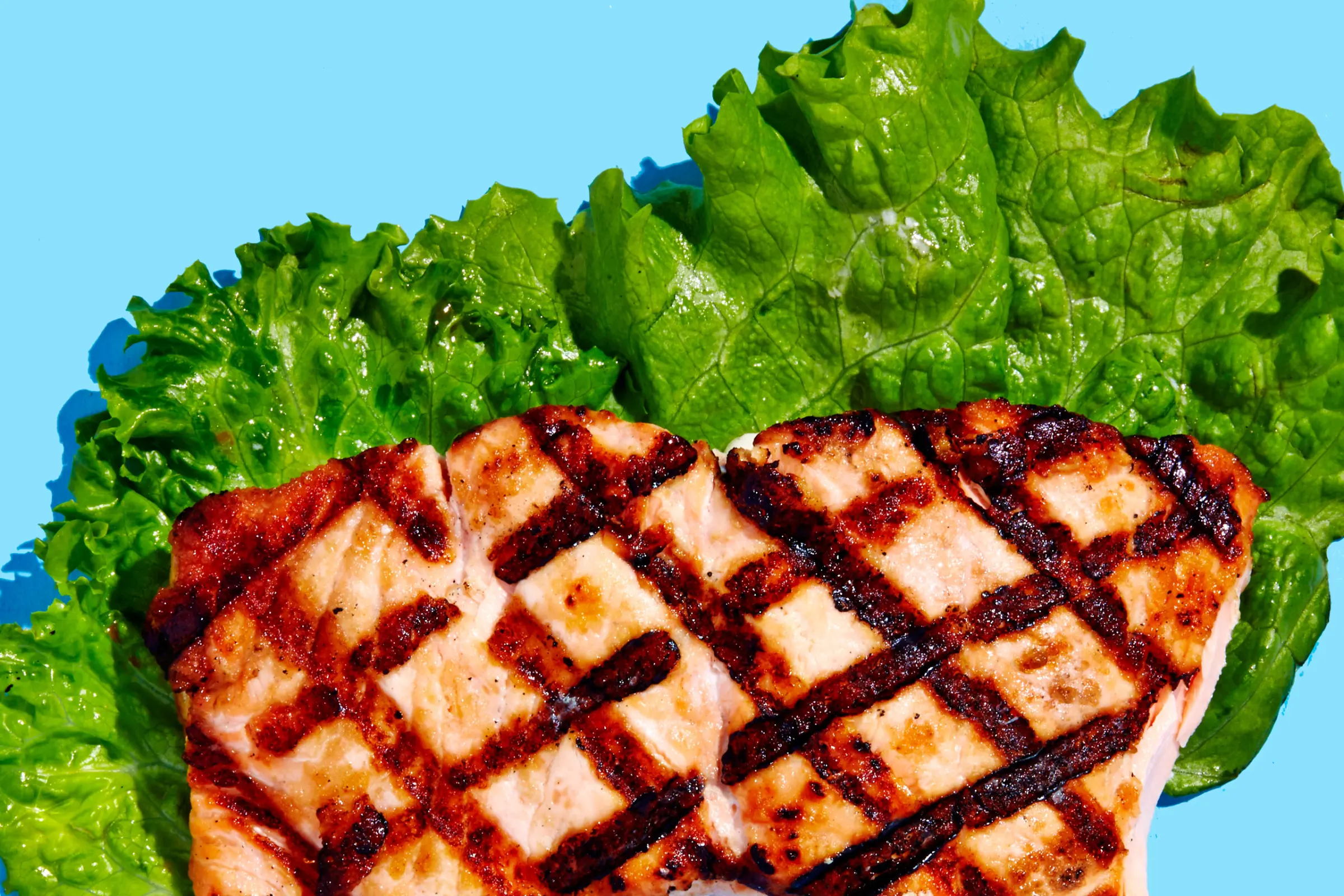

Salmon

Why it’s good for you: As we age, both intrinsic (our DNA) and extrinsic factors (the sun) take their toll. Skin can become dull, patchy, spotted and wrinkled, and while you might be tempted to go for a fancy face cream, what you eat may bring more potent results. How? Omega-3s in foods like salmon may help reduce dryness (from atopic dermatitis and psoriasis) and may even reduce the risk of skin cancer.

Serving size: 3 oz, cooked

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 175

Fat: 10.5 g

Cholesterol: 54 mg

Sodium: 52 mg

Carbohydrates: 0 g

Dietary fiber: 0 g

Sugars: 0 g

Protein: 18.8 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Margarita Salmon

Ingredients

1 teaspoon grated lime rind

3 tablespoons fresh lime or lemon juice

1 tablespoon tequila

2 teaspoons sugar

2 teaspoons vegetable oil

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon grated orange rind

1 garlic clove, crushed

4 (6-ounce) salmon fillets (about 1 inch thick)

8 ounces uncooked angel hair pasta

Cooking spray

Lime slices (optional)

Preparation

Combine first 8 ingredients in a large zip-top plastic bag; add fish to bag. Seal and marinate in refrigerator 20 minutes.

While fish is marinating, cook pasta according to package directions, omitting salt and fat. Drain and keep warm. Remove fish from bag, reserving marinade.

Preheat broiler.

Place fish on a broiler pan coated with cooking spray; broil 7 minutes or until fish flakes easily when tested with a fork, basting occasionally with reserved marinade. Serve over pasta. Garnish with lime slices, if desired.

Poultry (Dark Meat)

Why it’s good for you: Light meat is a fine choice, but there’s no reason to be afraid of the dark. The fat in dark meat contains a hormone called cholecystokinin, or CCK, which is partly responsible for satiety, so a little bit of dark meat can go a long way, especially if you’re watching your weight. Further, dark meat contains myoglobin, a protein which delivers oxygen to muscle cells. Dark meat also has more B vitamins than white meat, making it a nutrient-rich protein source that’s tasty and satisfying, and meat from the leg and thigh are rich in taurine. Studies have shown that taurine can lower the risk of coronary heart disease in women and it may also help protect against diabetes and high blood pressure.

Serving size: chicken, dark meat, cooked thigh (one example)

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 184

Fat: 8.7 g

Cholesterol: 137 mg

Sodium: 198 mg

Carbohydrates: 0 g

Dietary fiber: 0 g

Sugars: 0 g

Protein: 27 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Roasted Chicken Thighs Provençal

Ingredients

3 pounds small red potatoes, quartered

4 plum tomatoes, seeded and cut into 6 wedges

3 carrots, peeled and cut into 1-inch chunks

Cooking spray

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 1/2 tablespoons chopped fresh rosemary, divided

2 teaspoons chopped fresh thyme, divided

1 teaspoon salt, divided $

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper, divided

6 (6-ounce) skinless chicken thighs

24 niçoise olives

Rosemary sprigs (optional)

Preparation

Preheat oven to 425°.

Place potatoes, tomatoes, and carrots on a jelly-roll pan coated with cooking spray. Drizzle vegetable mixture with olive oil; sprinkle with 1 tablespoon chopped rosemary, 1 teaspoon thyme, 3/4 teaspoon salt, and 1/4 teaspoon pepper. Toss gently, and spread into a single layer on pan. Bake at 425° for 30 minutes. Remove vegetable mixture from pan, and keep warm.

Sprinkle chicken with remaining 1 1/2 teaspoons chopped rosemary, remaining 1 teaspoon thyme, remaining 1/4 teaspoon salt, and remaining 1/4 teaspoon pepper. Add chicken and olives to pan. Bake at 425° for 35 minutes or until chicken is done. Garnish with rosemary sprigs, if desired.

Whole Wheat Bread

Why it’s good for you: Fiber from whole grains can reduce the risk of colorectal cancer by nearly 40%, protecting gastrointestinal health. Foods labeled “high fiber” have 5 grams of fiber or more per serving, and the U.S. Dietary guidelines recommend making one-half of your daily grain servings whole. Just remember that the descriptors “whole grain” and “multi-grain” don’t necessarily mean the product is whole wheat.

Serving size: one slice

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 81

Fat: 1 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 146 mg

Carbohydrates: 13.7 g

Dietary fiber: 2 g

Sugars: 1 g

Protein: 4 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Whole-Wheat Orange Juice Muffins

Ingredients

1 1/2 cups all-purpose flour

1/2 cup whole-wheat flour

1/2 cup sugar

2 teaspoons baking powder

3/4 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 cup orange juice

1/4 cup vegetable oil

1 1/2 teaspoons grated lemon rind

1 large egg, lightly beaten

1/2 cup golden raisins

Cooking spray

Preparation

Preheat oven to 400°.

Lightly spoon flours into dry measuring cups; level with a knife. Combine all-purpose flour and next 5 ingredients (all-purpose flour through cinnamon) in a medium bowl; stir well with a whisk. Make a well in center of mixture. Combine juice, oil, rind, and egg; add to flour mixture, stirring just until moist. Stir in raisins. Spoon batter into 12 muffin cups coated with cooking spray. Sprinkle evenly with 1 tablespoon sugar. Bake at 400° for 20 minutes or until muffins spring back when touched lightly in center. Remove from pan. Cool completely on a wire rack.

Quinoa

Why it’s good for you: Quinoa is actually a seed, rich in amino acids. Just one serving provides all 9 essential amino acids, making it a good protein source for vegetarians. It also supplies anti-inflammatory phytonutrients and heart-healthy monounsaturated fatty acids, as well as vitamin E, zinc, folate and phosphorus.

Serving size: one cup, cooked

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 222

Fat: 3.6 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 13 mg

Carbohydrates: 39.4 g

Dietary fiber: 5 g

Sugars: 1.6 g

Protein: 8 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Nutty Almond-Sesame Red Quinoa

Ingredients

1 2/3 cups water

1 cup red quinoa

1/4 cup sliced almonds, toasted

2 tablespoons fresh lemon juice

2 teaspoons olive oil

2 teaspoons dark sesame oil

1/4 teaspoon kosher salt

3 green onions, thinly sliced

Preparation

Bring 1 2/3 cups water and quinoa to a boil in a medium saucepan. Reduce heat to low, and simmer 12 minutes or until quinoa is tender; drain. Stir in almonds, juice, oils, salt, and onions.

Hemp Seeds

Why they’re good for you: Hemp seed won’t get you high, but it can make you healthier. A seed from the cannabis sativa plant, this food contains easily digestible protein, all nine essential amino acids (just like flax), plus fatty acids, vitamin E and trace minerals. The seeds taste a bit like pine nuts.

Serving size: three tablespoons

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 170

Fat: 13 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: mg

Carbohydrates: g

Dietary fiber: g

Sugars: g

Protein: g

Recipe: Add a handful to smoothies, salads or oatmeal

Rolled Oats

Why they’re good for you: This hearty cereal grain is rich in a type of fiber called beta-glucan which has powerful, antimicrobial capabilities that boost immunity and lower cholesterol. The antioxidants in oats make this grain cardioprotective, plus they have the ability to stabilize blood sugar levels, lower diabetes risk and reduce the risk of certain cancers.

Serving size: ¼ cup dry

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 160

Fat: 2.5 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: mg

Carbohydrates: 27 g

Dietary fiber: 4 g

Sugars: 1 g

Protein: 5 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Cherry-Hazelnut Oatmeal

Ingredients

6 cups water

2 cups steel-cut oats (such as McCann’s)

2/3 cup dried Bing or other sweet cherries, coarsely chopped

1/4 teaspoon salt

5 tablespoons brown sugar, divided

1/4 cup chopped hazelnuts, toasted and divided

1/4 teaspoon ground cinnamon

2 tablespoons toasted hazelnut oil

Preparation

Combine the first 4 ingredients in a medium saucepan; bring to a boil. Reduce heat, and simmer 20 minutes or until desired consistency, stirring occasionally. Remove from heat. Stir in 3 tablespoons sugar, 1 tablespoon nuts, and cinnamon. Place 1 cup oatmeal in each of 6 bowls; sprinkle each serving with 1 teaspoon sugar. Top each serving with 1 1/2 teaspoon nuts; drizzle with 1 teaspoon oil.

Kamut

Why it’s good for you: Kamut is an ancient grain whose true origin isn’t clear. It looks like brown Basmati rice, but it has a more buttery, nutty and sweeter flavor. Kamut has 40% more protein than durum (traditional) wheat, and contains an array of polyphenols and vitamin E, selenium, magnesium, zinc, phosphorus and thiamin.

Serving size: one cup, cooked

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 227

Fat: 1.4 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 14 mg

Carbohydrates: 47.5 g

Dietary fiber: 7 g

Sugars: 5.3 g

Protein: 10 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Kamut, Lentil, and Chickpea Soup

Ingredients

3/4 cup kamut berries, rinsed

2 cups boiling water

2 tablespoons olive oil

2 cups finely chopped onion

1 cup finely chopped carrot

3/4 cup chopped fresh parsley

1/2 cup thinly sliced celery

1 tablespoon chopped fresh tarragon

2 teaspoons chopped fresh thyme

2 garlic cloves, minced

4 (14 1/2-ounce) cans fat-free, less-sodium chicken broth

2 bay leaves

1/3 cup dried lentils

1/4 teaspoon black pepper

1 (15-ounce) can chickpeas (garbanzo beans), rinsed and drained

2 teaspoons chopped celery leaves (optional)

Preparation

Place kamut in a small bowl. Carefully pour boiling water over kamut. Let stand 30 minutes; drain.

Heat oil in a stockpot over medium heat. Add onion, parsley, celery, tarragon, and thyme; cook 10 minutes, stirring occasionally. Add garlic; cook 2 minutes, stirring often.

Add kamut, broth, and bay leaves to onion mixture; bring to a boil. Cover, reduce heat, and simmer 30 minutes. Add lentils and pepper; cook 20 minutes or until lentils are tender. Discard bay leaves. Add chickpeas; simmer 2 minutes. Garnish with celery leaves, if desired.

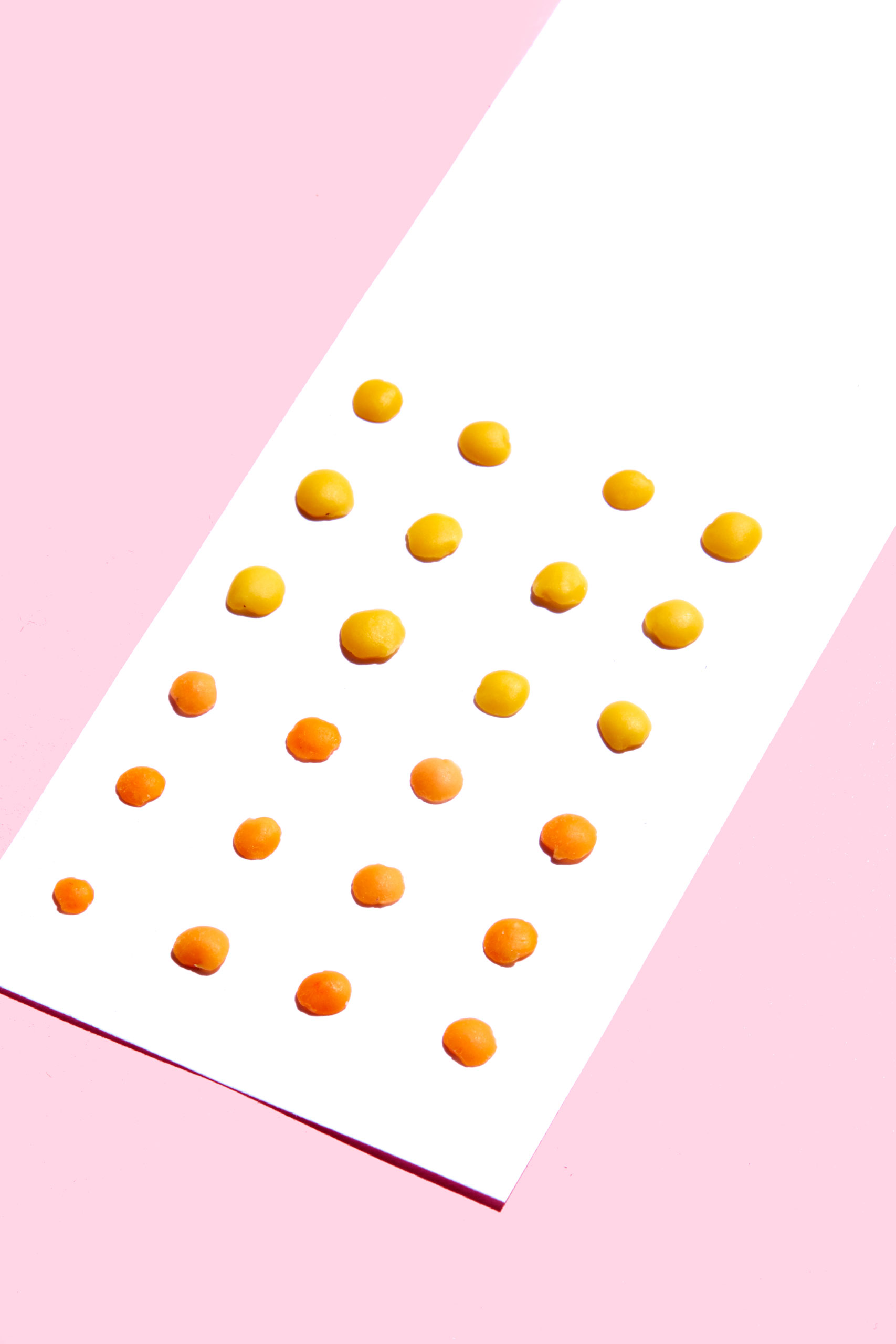

Lentils

Why they’re good for you: Lentils should be part of everyone’s diet, packing 18 grams of protein, 16 grams of fiber, and less than 1 gram of fat per cup. They contain nearly 30 percent more folate than spinach and they’re a source of zinc and B vitamins. Enjoying lentils can help guard against heart disease and stabilize blood sugar. Thanks to its iron content, lentils can support and maintain metabolism.

Serving size: one cup, cooked

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 230

Fat: 0.75 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 4 mg

Carbohydrates: 40 g

Dietary fiber: 1 g

Sugars: 0 g

Protein: 1 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Lentils with Wine-Glazed Winter Vegetables

Ingredients

3 cups water

1 1/2 cups dried lentils

1 teaspoon salt, divided

1 bay leaf

1 1/2 teaspoons olive oil

2 cups chopped onion

1 1/2 cups chopped peeled celeriac (celery root)

1 cup diced parsnip

1 cup diced carrot

1 tablespoon minced fresh or 1 teaspoon dried tarragon, divided

1 tablespoon tomato paste

1 garlic clove, minced

2/3 cup dry red wine

2 teaspoons Dijon mustard

1 tablespoon butter

1/4 teaspoon black pepper

Preparation

Combine water, lentils, 1/2 teaspoon salt, and bay leaf in a medium saucepan; bring to a boil. Reduce heat, and simmer 25 minutes. Remove lentils from heat, and set aside.

Heat olive oil in a medium cast-iron or nonstick skillet over medium-high heat. Add the onion, celeriac, parsnip, carrot, and 1 1/2 teaspoons tarragon, and sauté 10 minutes or until browned. Stir in 1/2 teaspoon salt, tomato paste, and garlic; cook mixture 1 minute. Stir in wine, scraping pan to loosen browned bits. Bring to a boil; cover, reduce heat, and simmer 10 minutes or until vegetables are tender. Stir in mustard. Add lentil mixture, and cook 2 minutes. Remove from heat; discard bay leaf, and stir in butter, 1 1/2 teaspoons tarragon, and pepper.

Farro

Why it’s good for you: Farro is an ancient ancestor of wheat. The whole grain variety requires overnight soaking and 30 to 40 minutes on the stovetop to yield a tender grain. Farro is lower in calories and higher in muscle-building protein and cancer-fighting fiber than other whole grains, and it’s rich in B vitamins and zinc.

Serving size: ¼ cup

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 200

Fat: 1.5 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 0 mg

Carbohydrates: 37 g

Dietary fiber: 7 g

Sugars: 0 g

Protein: 7 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Farro Salad with Roasted Beets, Watercress, and Poppy Seed Dressing

Ingredients

2 bunches small beets, trimmed

2/3 cup uncooked farro

3 cups water

3/4 teaspoon kosher salt, divided

3 cups trimmed watercress

1/2 cup thinly sliced red onion

1/2 cup (2 ounces) crumbled goat cheese

2 tablespoons cider vinegar

2 tablespoons toasted walnut oil

2 tablespoons reduced-fat sour cream

1 1/2 teaspoons poppy seeds

2 teaspoons honey

1/2 teaspoon black pepper

2 garlic cloves, crushed

Preparation

Preheat oven to 375°.

Wrap beets in foil. Bake at 375° for 1 1/2 hours or until tender. Cool; peel and thinly slice.

Place farro and 3 cups water in a medium saucepan; bring to a boil. Reduce heat, and simmer 25 minutes or until farro is tender. Drain and cool. Stir in 1/2 teaspoon salt.

Arrange 1 1/2 cups watercress on a serving platter; top with half of farro, 1/4 cup onion, and half of sliced beets. Repeat layers with remaining 1 1/2 cups watercress, remaining farro, remaining 1/4 cup onion, and remaining beets. Sprinkle top with cheese.

Combine remaining 1/4 teaspoon salt, vinegar, and remaining ingredients; stir well with a whisk. Drizzle vinegar mixture evenly over salad.

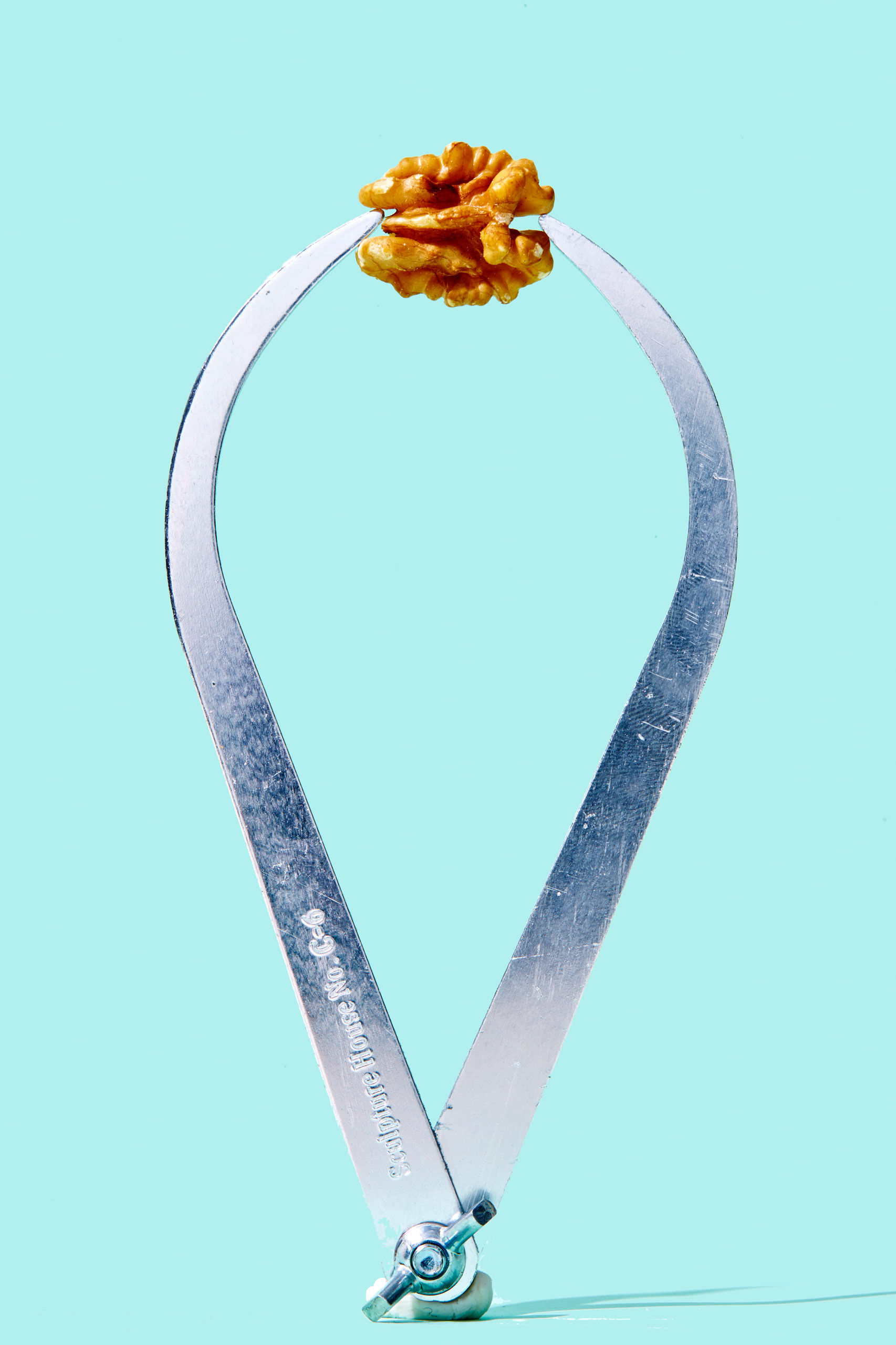

Walnuts

Why they’re good for you: Walnuts are a tasty source of plant-based fatty acids and boasts more polyphenols than red wine. Having 4 grams of protein per ounce, walnuts also have the ability to keep your heart healthy. They contain cancer-fighting properties, support weight control and, in some studies, have been shown to be neuroprotective.

Serving size: half a cup

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 327

Fat: 33 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 1 mg

Carbohydrates: 7 g

Dietary fiber: 3.4 g

Sugars: 1 g

Protein: 8 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Wild Rice and Walnut Pilaf

Ingredients

1 teaspoon butter

1/4 cup finely chopped onion

2 1/2 cups water

3/4 cup long-grain brown and wild rice blend (such as Lundberg’s)

1/2 teaspoon salt, divided

2 tablespoons chopped fresh parsley

1 tablespoon chopped fresh chives

1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice

1 teaspoon olive oil

2 tablespoons chopped walnuts, toasted

Preparation

Melt butter in a small saucepan over medium heat. Add onion; cook 3 minutes, stirring frequently. Stir in water, rice, and 1/4 teaspoon salt; bring to a boil. Cover, reduce heat, and simmer 40 minutes or until liquid is absorbed. Remove from heat; stir in 1/4 teaspoon salt, parsley, chives, juice, and oil. Sprinkle each serving with walnuts.

Almonds

Why they’re good for you: Rich in monounsaturated fats, almonds have been shown to be helpful in keeping cholesterol levels within a healthy range. They’re also effective prebiotics, feeding the probiotics in our gut, and they help support a robust immune system. Almonds, like all nuts, are good sources of the antioxidant vitamin E, which may play a role in slowing cognitive decline with age.

Serving size: five almonds

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 35

Fat: 3 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 0 mg

Carbohydrates: 1.3 g

Dietary fiber: 0.8 g

Sugars: 0.3 g

Protein: 1.3 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Almond Green Beans

Ingredients

1 tablespoon butter

1/4 cup slivered almonds

2 teaspoons minced fresh garlic

12 ounces trimmed green beans

3 tablespoons water

1/4 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

Preparation

Melt butter in a large skillet over medium heat. Add almonds; cook 2 minutes or until lightly browned, stirring constantly. Remove from pan with a slotted spoon. Add garlic to pan; cook 30 seconds, stirring constantly. Add green beans, water, salt, and pepper. Cover and cook 4 minutes or until beans are tender and liquid evaporates. Sprinkle with almonds.

Chia Seeds

Why they’re good for you: Despite their tiny size, chia seeds deliver an incredible amount of nutrition. In a two-tablespoon serving, you’ll find 11 grams of fiber, four grams of protein, five grams of plant-based omega-3 fatty acids, nearly 20 percent of a day’s worth of calcium, plus potassium and antioxidants.

Serving size: 1 oz.

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 138

Fat: 8.7 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 5 mg

Carbohydrates: 12 g

Dietary fiber: 10 g

Sugars: 0 g

Protein: 4.7 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Five-Seed Bread

Ingredients

1/4 cup unsalted, roasted sunflower seeds kernels

1 tablespoon chia seeds

1 tablespoon caraway seeds

1 tablespoon sesame seeds

1 teaspoon poppy seeds

2 tablespoons honey

1 package dry yeast (about 2 1/4 teaspoons)

1 1/2 cups warm water (100° to 110°)

4.2 ounces sweet white sorghum flour (about 1 cup)

3.9 ounces potato starch (about 3/4 cup)

2.3 ounces cornstarch (about 1/2 cup)

1 tablespoon xanthan gum

1 teaspoon baking powder

1 teaspoon sea salt

1/4 cup canola oil

1 teaspoon white vinegar

2 large eggs, lightly beaten

Preparation

Combine first 5 ingredients in a small bowl, stirring to combine. Set aside.

Dissolve honey and yeast in 1 1/2 cups warm water in a medium bowl; let stand 5 minutes.

Weigh or lightly spoon flour, potato starch, and cornstarch into dry measuring cups; level with a knife. Place flour, potato starch, cornstarch, xanthan gum, baking powder, and salt in a large bowl; beat with a mixer at medium speed until blended. Add seed mixture, yeast mixture, oil, vinegar, and eggs; beat at low speed until blended.

Spoon batter into a 9 x 5-inch loaf pan coated with cooking spray. Cover with plastic wrap coated with cooking spray, and let rise in a warm place (85°), free from drafts, 45 minutes or until dough reaches top of pan.

Preheat oven to 375°.

Bake at 375° for 45 minutes or until loaf sounds hollow when tapped. Cool 10 minutes in pan on a wire rack; remove from pan. Cool completely on wire rack.

Flaxseeds

Why they’re good for you: This tiny seed has more than 100 times the amount of phytonutrients as oats, wheat bran, millet and buckwheat. Flaxseed is a source of plant-based fatty acids, fiber, B vitamins, potassium and minerals like calcium and iron. Research suggests that flaxseed may lower cholesterol, help fight cancer, and lower the risk of osteoporosis.

Serving size: 1 tbsp.

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 55

Fat: 4 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 3 mg

Carbohydrates: 3 g

Dietary fiber: 3 g

Sugars: 0.2 g

Protein: 2 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Confetti Rice Pilaf with Toasted Flaxseed

Ingredients

1/4 cup flaxseed

2 teaspoons olive oil

1 cup chopped onion

1 cup uncooked basmati or long-grain rice

1 (16-ounce) can fat-free, less-sodium chicken broth

1/4 cup chopped fresh parsley

2 teaspoons grated lemon rind

1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon black pepper

Preparation

Place flaxseed in a small nonstick skillet; cook over low heat 5 minutes or until toasted, stirring constantly. Place flaxseed in a blender; process just until chopped.

Heat oil in a saucepan over medium heat until hot. Add onion; cook over medium heat 3 minutes or until tender. Add rice. Cook 1 minute; stir constantly. Stir in broth; bring to a boil. Reduce heat; simmer 20 minutes or until rice is tender. Remove from heat; fluff with fork. Stir in flaxseed and remaining ingredients.

Note: Flaxseed keeps best when stored in the refrigerator.

Eggs

Why they’re good for you: Eggs deliver essential vitamins and minerals in a very small package. Plus, they’re a low-calorie, low-fat source of extremely digestible protein. The egg yolk, in particular, is a source of choline, important for proper cell and nerve function. Experts say you can eat up to two eggs daily—because cholesterol in the diet does not appear to have an impact on cholesterol in the blood.

Serving size: one large egg

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 72

Fat: 5 g

Cholesterol: 186 mg

Sodium: 71 mg

Carbohydrates: 0.36 g

Dietary fiber: 0 g

Sugars: 0.2 g

Protein: 6.3 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Marinara Poached Eggs

Ingredients

3 cups Slow Cooker Marinara

1/2 teaspoon crushed red pepper

4 eggs

Toast

Preparation

Bring marinara and crushed red pepper to a simmer in a skillet. Make 4 wells in marinara; crack 1 egg into each. Cook, covered, 6 minutes or until desired degree of doneness. Serve with toast.

Kefir

Why it’s good for you: This fermented milk drink is a cocktail of good-for-you microbia. It’s been shown to support immunity, improve lactose intolerance (despite that sounding counterintuitive), build bone density and fight cavities by minimizing oral bacteria. As with other dairy products, Kefir is rich in calcium, phosphorus, magnesium and protein.

Serving size: one cup

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 210

Fat: 14 g

Cholesterol: 55 mg

Sodium: 120 mg

Carbohydrates: 12 g

Dietary fiber: 0 g

Sugars: 12 g

Protein: 8 g

Recipe: Add it to smoothies instead of milk or yogurt

2% Greek Yogurt

Why it’s good for you: Conventional yogurt is an excellent source of calcium, potassium and protein, but the Greek varieties have double the protein, half the sodium and half the carbohydrates of regular yogurt. Probiotics such as Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus casei are often added to yogurt, increasing healthy gut bacteria and bolstering immunity. While fat-free Greek yogurt has fewer calories than one percent Greek yogurt, the later has the ability to make fat-soluble vitamins (such as A,D,E and K) more bioavailable to the body and helps with satiety.

Serving size: 7 ounces

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 150

Fat: 4 g

Cholesterol: 13 mg

Sodium: 66 mg

Carbohydrates: 8 g

Dietary fiber: 0 g

Sugars: 8 g

Protein: 20 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Creamy Spinach and Feta Dip

Ingredients

6 ounces nonfat Greek yogurt

3/4 cup crumbled feta cheese

2 ounces 1/3-less-fat cream cheese, softened

1/4 cup low-fat sour cream

1 garlic clove, crushed

1 1/2 cups finely chopped fresh spinach

1 tablespoon fresh dill

1/8 teaspoon black pepper

Preparation

Place yogurt, feta cheese, cream cheese, sour cream, and crushed garlic clove in a food processor; process until smooth. Spoon yogurt mixture into a medium bowl; stir in spinach, fresh dill, and black pepper. Cover and chill.

Coconut Oil

Why it’s good for you: Despite being high in saturated fat, coconut oil may good for your heart, weight and energy levels. Coconut oil is comprised of medium chain triglycerides (MCTs) which are easily digested and have been shown to help the body burn fat and increase “good” cholesterol levels. More than 50% of coconut oil is comprised of lauric acid, and while lauric acid increases bad cholesterol, it raises your good cholesterol that much more. Some studies suggest improved exercise performance related to MCT consumption, but the data is not yet convincing.

Serving size: one tbsp

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 117

Fat: 13.6 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 0 mg

Carbohydrates: 0 g

Dietary fiber: 0 g

Sugars: 0 g

Protein: 0 g

Recipe from Tina Ruggiero: Coconut & Sesame Crusted Salmon

Ingredients

2 tablespoon panko

2 teaspoon toasted black & white sesame seeds

2 tablespoon unsweetened coconut

1 teaspoon sesame oil

4 (4 oz.) salmon fillets

2 teaspoon Dijon mustard

2 teaspoon coconut oil

Preparation

In a small bowl, combine the panko, sesame seeds, coconut and sesame oil. Reserve.

Sprinkle the salmon with salt and pepper to taste. Spread ½ tsp. Dijon on one side of each fillet. Divide the coconut mixture between the salmon fillets, pressing it onto the Dijon.

Heat a medium sauté pan over medium heat. Add the coconut oil and when it shimmers, add the salmon, coconut-side down, and cook for about 2 minutes or until golden. Turn the salmon and brown the other side, another 2 minutes. Turn heat down and continue to cook to desired doneness.

Olive Oil

Why it’s good for you: Due to its phenolic compounds, olive oil is enjoyed for its anti-inflammatory benefits in addition to its taste. It’s also recognized for contributing to lower rates of heart disease and obesity. The extra virgin variety retains the most number of antioxidants, since the oil comes from the first pressing of olives. No matter what variety is enjoyed, experts agree that olive oil has anti-cancer, cognitive, bone, cardiovascular and digestive health benefits.

Serving size: 1 tbsp

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 119

Fat: 13.5 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 0 mg

Carbohydrates: 0 g

Dietary fiber: 0 g

Sugars: 0 g

Protein: 0 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Seared Scallops with Roasted Tomatoes

Ingredients

3 cups grape tomatoes

Cooking spray

1/2 teaspoon kosher salt, divided

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper, divided

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 1/2 pounds sea scallops

2 tablespoons thinly sliced fresh basil

Preparation

Preheat broiler.

Arrange tomatoes in a single layer in a shallow roasting pan; lightly coat tomatoes with cooking spray. Sprinkle tomatoes with 1/4 teaspoon salt and 1/4 teaspoon pepper; toss well to coat. Broil 10 minutes or until tomatoes begin to brown, stirring occasionally.

While tomatoes cook, heat oil in a large cast-iron skillet over medium-high heat. Pat scallops dry; sprinkle both sides of scallops with remaining 1/4 teaspoon salt and remaining 1/4 teaspoon pepper. Add scallops to skillet; cook 2 minutes on each side or until desired degree of doneness. Serve scallops with tomatoes; sprinkle with basil.

Cumin

Why it’s good for you: Cumin may be a common kitchen spice, but its health benefits are more than ordinary. Ground cumin may support heart health, fight infection, and combat inflammation; just one-half teaspoon of ground cumin has twice as many antioxidants as a carrot.

Serving size: one tsp.

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 8

Fat: 0.5 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 4 mg

Carbohydrates: 0.9 g

Dietary fiber: 0.2 g

Sugars: 0.05 g

Protein: 0.4 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Cumin-Dusted Salmon Fillets

Ingredients

1 teaspoon ground cumin

1 teaspoon paprika

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

4 (6-ounce) salmon fillets (about 1 inch thick), skinned

Cooking spray

Preparation

Combine first 4 ingredients in a small bowl. Sprinkle both sides of fish with spice mixture.

Heat a large nonstick skillet coated with cooking spray over medium heat, and add fish. Cook 6 minutes on each side or until fish flakes easily when tested with a fork.

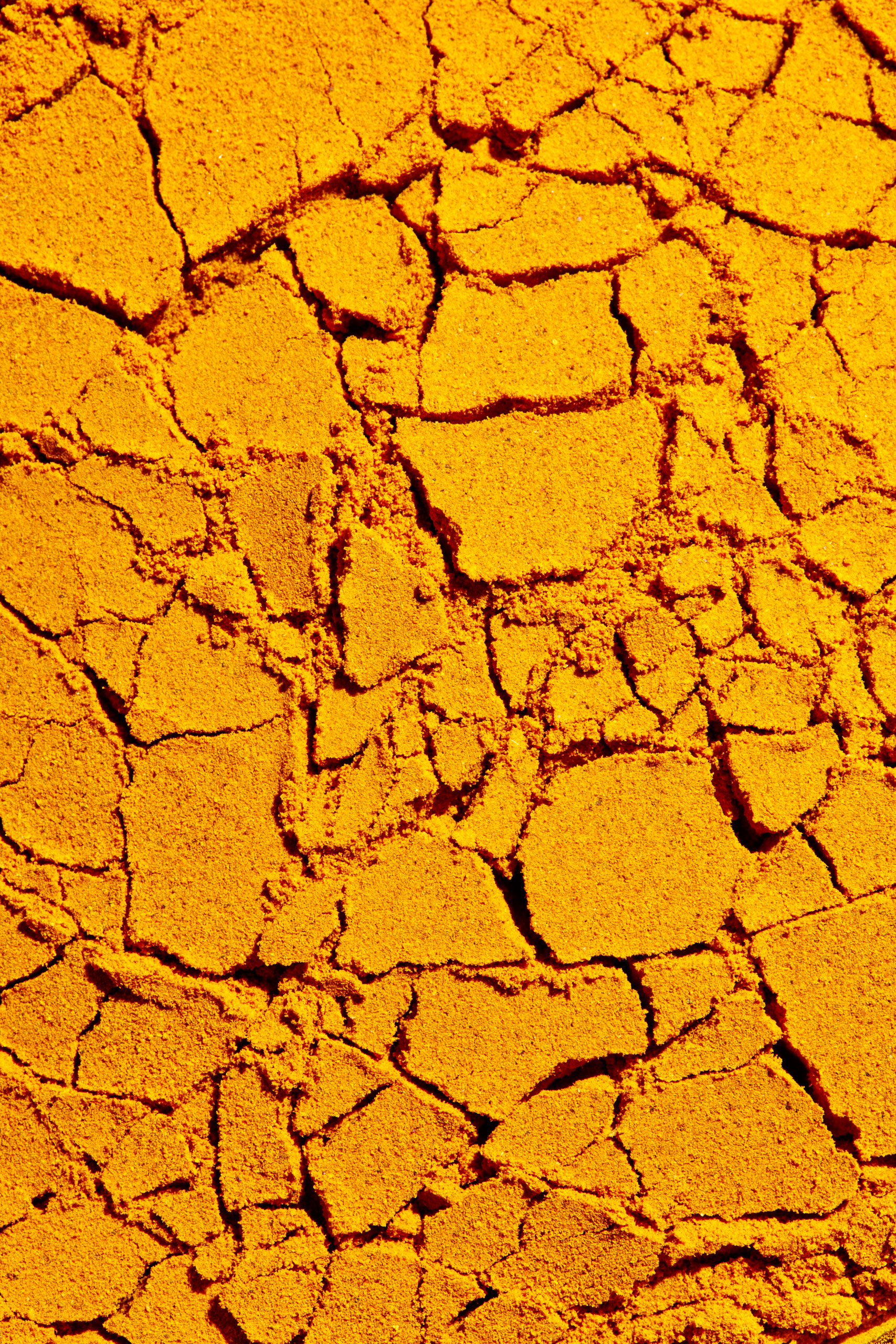

Turmeric

Why it’s good for you: Turmeric is a spice that comes from the root of the Curcuma longa plant, and its vibrant, orange color comes from curcumin. This pigment has been shown to be a potent anti-viral and anti-inflammatory agent. Some research has shown turmeric to be helpful in preventing Alzheimer’s and cancer.

Serving size: one tsp

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 9

Fat: 0.1 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 1 mg

Carbohydrates: 2 g

Dietary fiber: 0.7 g

Sugars: 0.1 g

Protein: 0.3 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Omelet with Turmeric, Tomato, and Onions

Ingredients

4 large eggs

3/8 teaspoon kosher salt

1 tablespoon olive oil

1/4 teaspoon brown mustard seeds

1/8 teaspoon turmeric

2 green onions, finely chopped

1/4 cup diced plum tomato

Dash of black pepper

Preparation

Whisk together eggs and salt.

Heat oil in a large cast-iron skillet over medium-high heat. Add mustard seeds and turmeric; cook 30 seconds or until seeds pop, stirring frequently. Add onions; cook 30 seconds or until soft, stirring frequently. Add tomato; cook 1 minute or until very soft, stirring frequently.

Pour egg mixture into pan; spread evenly. Cook until edges begin to set (about 2 minutes). Slide front edge of spatula between edge of omelet and pan. Gently lift edge of omelet, tilting pan to allow some uncooked egg mixture to come in contact with pan. Repeat procedure on the opposite edge. Continue cooking until center is just set (about 2 minutes). Loosen omelet with a spatula, and fold in half. Carefully slide omelet onto a platter. Cut omelet in half, and sprinkle with black pepper.

Cinnamon

Why it’s good for you: Cinnamon’s health benefits come from the oil found in in its bark. These essential oils are suspected to have anti-clotting and antimicrobial power along with possessing the ability to reduce inflammation. Research shows that cinnamon may have the ability to improve insulin response as well as boost brain and colon health.

Serving size: one tsp.

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 6

Fat: 0 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 0 mg

Carbohydrates: 2 g

Dietary fiber: 1 g

Sugars: 0 g

Protein: 0.1 g

Recipe from Cooking Light: Cinnamon-Soy Braised Pork

Ingredients

1 1/4 cups water

1/3 cup canola oil

3 tablespoons sugar

1 teaspoon kosher salt

2 cups matzo meal

4 large eggs

1/2 cup sugar

2 tablespoons ground cinnamon

Preparation

Preheat oven to 375°.

Cover a large, heavy baking sheet with parchment paper; set aside.

Combine first 4 ingredients in a medium saucepan over medium-high heat; bring to a boil. Reduce heat to low; add matzo meal to pan, stirring well with a wooden spoon until mixture pulls away from sides of pan (about 30 seconds). Remove from heat; place dough in bowl of a stand mixer. Cool slightly. Add eggs, 1 at a time, beating at low speed with paddle attachment until dough is smooth, scraping sides and bottom of bowl after each egg.

Combine 1/2 cup sugar and cinnamon in a medium bowl.

With moistened fingers, shape 1/4 cupfuls of dough into mounds; roll in sugar mixture to coat, and place 2 inches apart onto prepared pan. Bake at 375° for 50 minutes or until browned and crisp. Remove from oven; cool on wire rack.

Rooibos Tea

Why it’s good for you: Rooibos (roy-bus) tea, a red tea packed with antioxidants that guard us from chronic and degenerative diseases alike, is rich in minerals like calcium and iron.

Serving size: one tea bag

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 0

Fat: 0 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 0 mg

Carbohydrates: 0 g

Dietary fiber: 0 g

Sugars: 0 g

Protein: 0 g

Recipe: Add to hot water, enjoy.

Red Wine

Why it’s good for you: Resveratrol, a polyphenol found in the skin of red grapes and in red wine, has been recognized for its antioxidant and anti-cancer properties. Scientists believe the flavonoids found in red wine lower the risk of coronary artery disease by reducing clotting, bad cholesterol and by boosting good cholesterol levels. The sweeter the wine, the fewer the flavonoids it contains. Cabernet, Petit Syrah and Pinot Noir have the most.

Serving size: one glass

Nutrition per serving:

Calories: 125

Fat: 0 g

Cholesterol: 0 mg

Sodium: 6 mg

Carbohydrates: 4 g

Dietary fiber: 0 g

Sugars: 1 g

Protein: 0.1 g

Recipe: Pour yourself a glass and enjoy.

MORE Calorie vs. Calorie: Study Evaluates Three Diets for Staying Slim

Modest weight loss can also seed good eating habits that can keep weight loss going, or maintain weight at a healthy level. “Modest weight loss on average can translate to a big public-health impact” on the obesity epidemic, says Dr. Christina Wee, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the obesity-and-health-behaviors research program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Fewer overweight and obese individuals mean fewer cases of diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, joint disorders and more. So for doctors faced with advising their patients on how to best manage their weight, these are the first bits of evidence that some commercial programs — Weight Watchers and Jenny Craig — might be better than others in helping patients to slim down and stay that way.