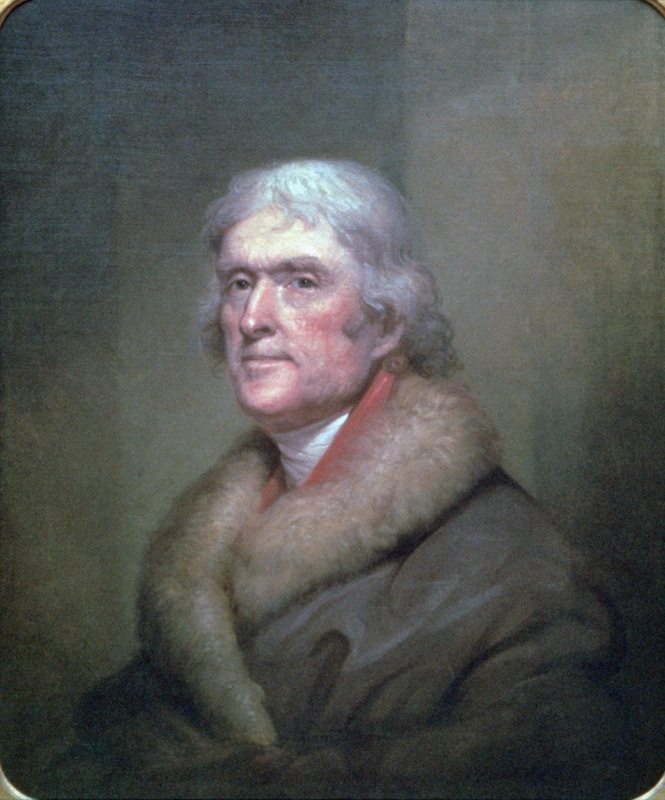

It’s hard to imagine a version of American history in which Thomas Jefferson, born on this day, April 13, in 1743, was never President. And yet, before he became the United States’ third President, he nearly walked away from politics entirely.

As Walter Kirn explained as part of a special 2005 TIME report on Thomas Jefferson’s legacy, the vast trove of letters that Jefferson left behind reveals that he was pretty sure he was done with politics in 1781, a full two decades before his inauguration:

The war he had helped launch and justify raged on, the enemy’s army had swept through his state capital only hours before and his successor as Virginia’s Governor still hadn’t been selected by the legislature, but Thomas Jefferson was going home, convinced that his work for America was done. It was the summer of 1781, five years since the July in Philadelphia when the author of the Declaration of Independence had, in two inspired weeks of writing energized by years of thought and study and practical political activity, helped create a new nation with his pen. The course this nation would follow remained uncertain, the fate of its central ideals undecided and the question of its very survival unclear, but Jefferson’s direction was firm and fixed: away from politics and public life and back to his cherished plantation, Monticello. Back to his loved ones, his gardens, his fields, his library and to the scores of people whose labor made his pursuit of happiness possible: his slaves.

The great revolutionary was calling it quits–or so he told his friends. In one of more than 20,000 letters that scholars estimate Jefferson completed before his death on July 4, 1826, the future Secretary of State, Vice President, two-term President and founder of the University of Virginia confirmed his premature decision to abandon the rigors of government service for the pleasures of rural solitude: “I have taken my final leave of everything of that nature, have retired to my farm, my family and books from which I think nothing will ever more separate me.”

That, of course, turned out not to be true. (“Nearly everything he wrote was contradicted at some point by something he did,” Kirn notes, from that very letter to his stance on slavery.) There’s no easy answer as to why Jefferson changed his mind, but by doing so he continued his strong track record of changing history.

Read TIME’s 2005 special issue about Thomas Jefferson, here in the archives: Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Thomas Jefferson

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com