For most of this week, Germanwings airlines has struggled to answer questions about the mental health of one of its co-pilots, Andreas Lubitz, who stands accused of crashing a plane full of passengers into the French Alps on Tuesday, killing everyone on board. But a stubborn set of legal barriers has hindered their search for information: Germany’s data protection and privacy laws.

Carsten Spohr, the head of Lufthansa airlines, the parent company of Germanwings, was not even able to answer basic questions about the co-pilot’s medical history during a press conference held on Thursday. He could not say, for instance, whether Lubitz had taken a break from his flight training due to illness. “In the event that there was a medical reason for the interruption of the training, medical confidentiality in Germany applies to that, even after death,” Spohr explained. “The prosecution can look into the relevant documents, but we as a company cannot.”

That is because privacy protections in Germany are among the most stringent in the world. Under their provisions, an airline has to rely on the truthfulness of its pilots in learning about their medical histories, and it has no legal means of checking the information the pilots provide.

“There is no general rule that obliges doctors of pilots to report medical conditions relevant to their ability to fly to the authorities,” says Ulrich Wuermeling, a Frankfurt-based lawyer who works on privacy law. On the contrary, a German doctor who reports such information could face criminal charges for violating his patients’ privacy.

The flaws in that system came into focus on Friday, when prosecutors accused the Germanwings co-pilot of hiding his mental illness from his employers. In his home in the city of Dusseldorf, prosecutors claim to have found a sick note excusing Lubitz from work on the day of the catastrophe. But the note had been torn up.

The identity of the doctor who wrote the note is still unclear. But under German law, only Lubitz – and not his doctor – would have had the legal right to disclose the details of his health to his employers at Germanwings.

“In practice, if you are sick and your doctor finds you unfit for work, he gives you an illness-based work exemption,” says Christian Runte, a German lawyer and expert on data protection. “It doesn’t say what the illness is. It just says you are unfit for work. And it is up to the patient whether they want to tell that to the employer or not.”

Based on the German prosecutors’ findings so far, it seems Lubitz decided not to use the work exemption on the day of the disaster and instead took his seat inside the cockpit of Germanwings Flight 9525. French prosecutors investigating the crash of that plane have since accused him of deliberately crashing the aircraft after the flight captain left him alone at the controls.

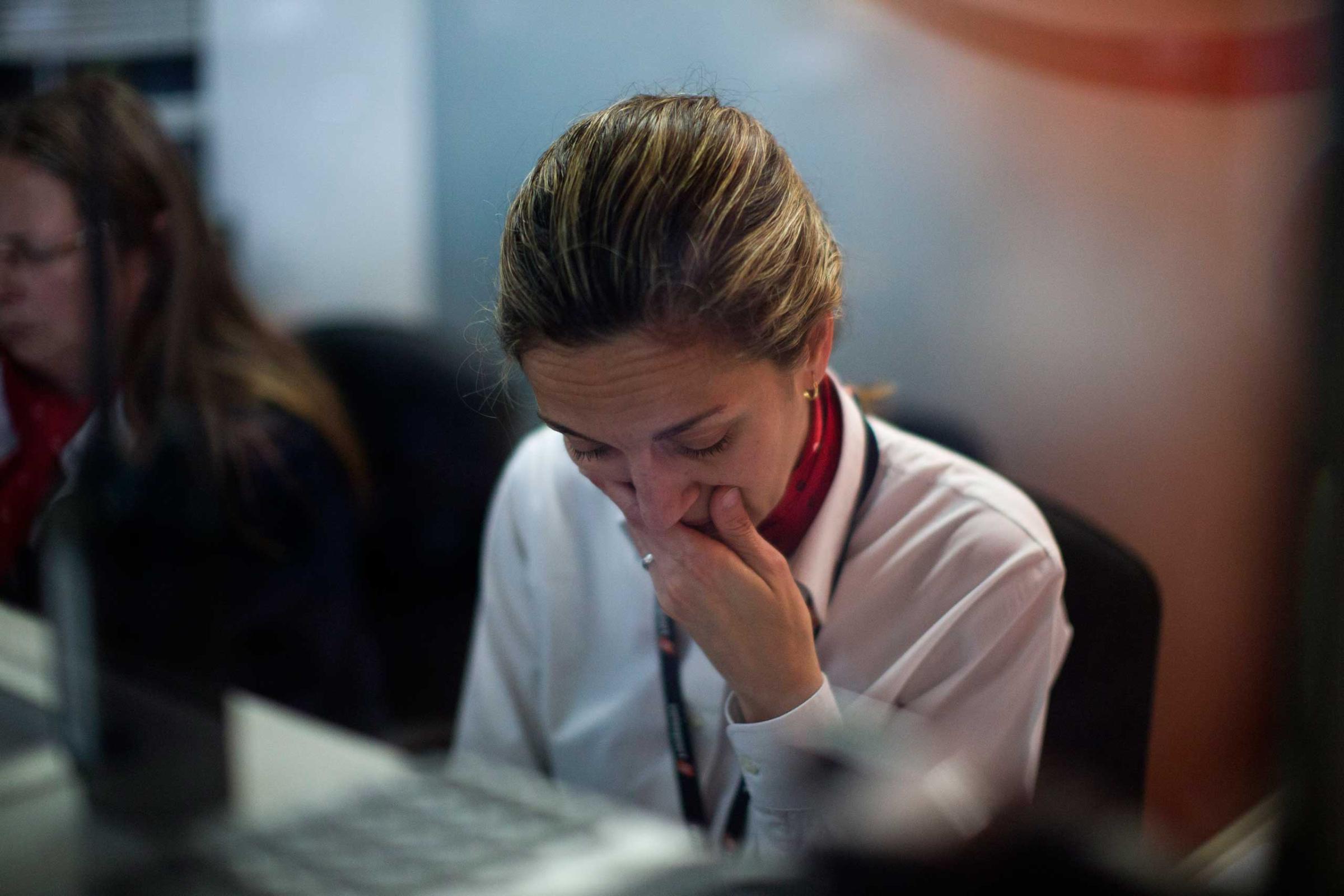

The incident has raised some troubling questions about lack of communication between Lubitz’s doctors and his employers at Germanwings. On Friday, the university clinic in Dusseldorf, where Lubitz was receiving care for an undisclosed condition, denied media reports that he was being treated for depression. But in describing their “preliminary assessment” of the evidence, the city’s prosecutor said earlier in the day that Lubitz “hid his illness from his employer and colleagues.”

In order to provide Germanwings with any details about Lubitz’s mental health, his doctors would likely have needed his express permission. “Therefore the doctor would not be in a position to inform the company directly even if he knows that this person is a pilot,” says Wuermeling, the lawyer in Frankfurt.

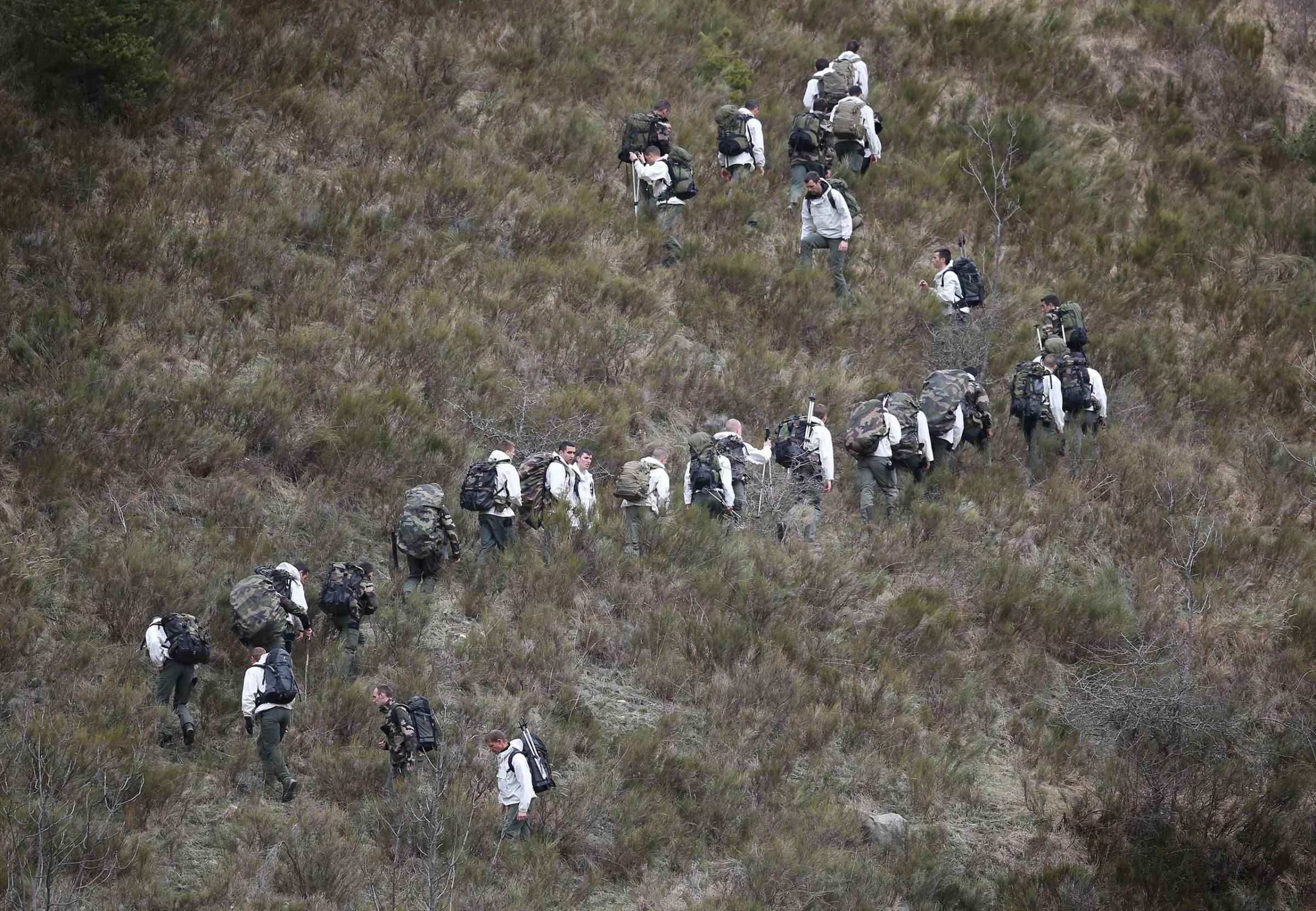

Witness Scenes From the Plane Crash in the French Alps

In some rare cases, doctors have been able to invoke the interests of public safety in trying to circumvent German privacy law. The Higher Regional Court of Frankfurt, for instance, even ruled in 1999 that a doctor was legally obligated to breach a patient’s confidentiality, because that patient refused to inform close relatives that he was HIV-positive.

But as a rule, when the German legal system is compared to those in the U.S. and other European states, Germany gives more weight to personal privacy than to public safety, legal experts say. Employers are even restricted in checking the criminal records of the people they are seeking to hire, as under German law, the employer must usually rely on the applicants themselves to provide such information voluntarily.

Part of the reason for this approach to privacy is rooted in Germany history. “In the end it probably goes back to the Nazi regime,” says Wuermeling. “The Nazis basically justified enormous infiltration into personal privacy with national security reasons.”

In communist East Germany, the secret police force known as the Stasi also practiced wholesale surveillance of its citizens. So as early as 1971, democratic West Germany enacted strict privacy protections, well before any such guidelines became the norm in other parts of Europe. The reunification of Germany in 1990 extended those protections to all German citizens.

In the wake of Tuesday’s air disaster, however, Germany may have to reconsider the way it balances privacy against security, at least in allowing airlines the ability to screen their pilots more thoroughly. Even a week ago, data protection authorities in Germany would likely have objected to a request from Germanwings asking doctors to reveal the details of their pilots’ mental health, says Runte. “But if you ask the same question today, I think the answer could be different.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com