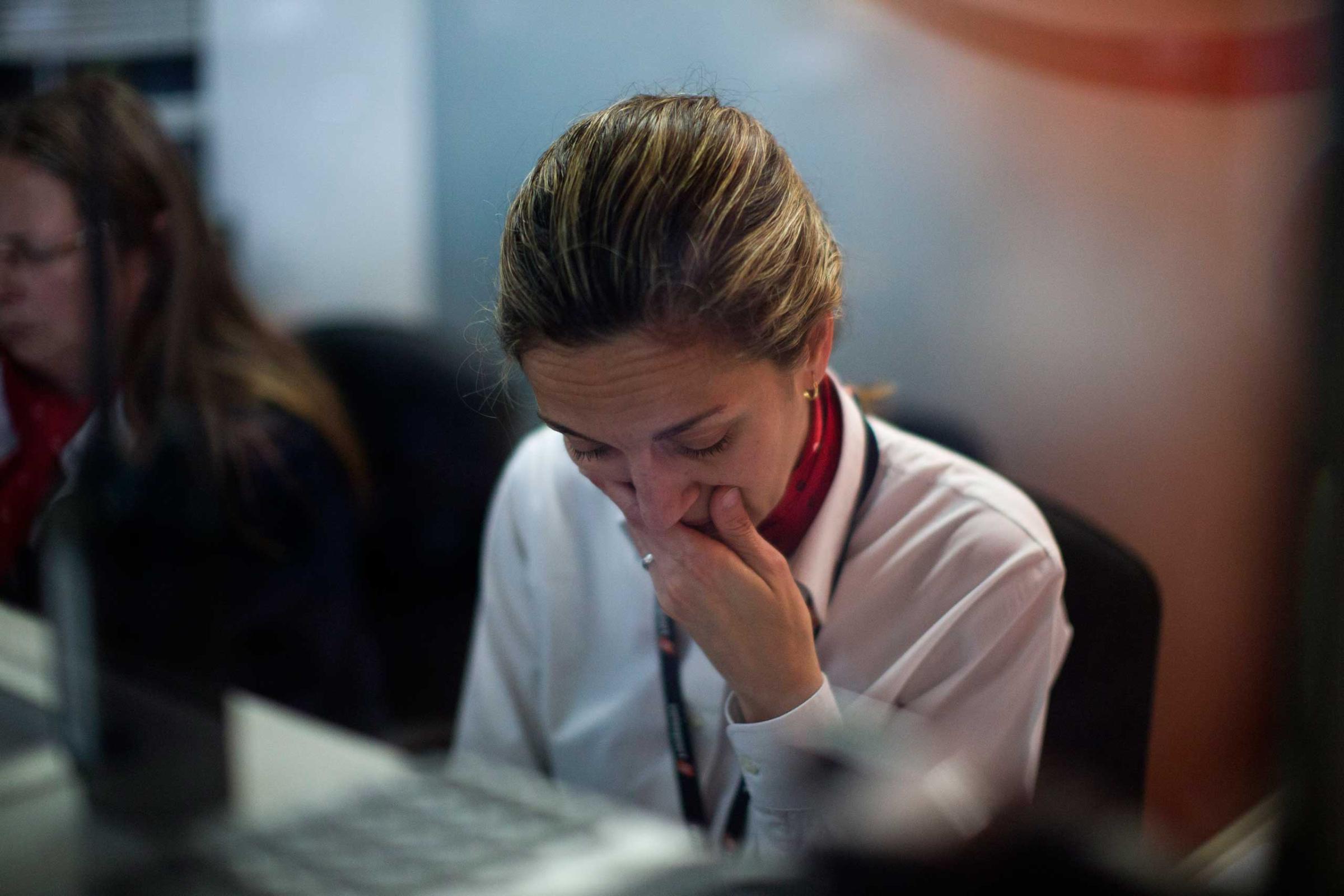

As investigators continue to search for clues about the crash of Germanwings Flight 9525, a new theory has emerged: a French prosecutor said on Thursday that the flight’s co-pilot brought the plane down on purpose.

Black box recordings suggest that when the pilot left the cockpit, the co-pilot locked the door and deliberately flew the plane into the mountain, not responding to the pilot’s pounding on the door or, in fact, saying a single word during the descent.

The shocking revelation may remind observers of another crash, when on Oct. 31, 1999, Egyptair Flight 990 went down on its way from New York City to Cairo. When the black box from that flight was retrieved, this, as per TIME’s recounting, was what was heard:

The cockpit door opens, then closes. Silence. After four or five minutes, a calm voice utters three words in Arabic. “Tawakalt ala Allah”: “I put my faith in God,” or “I entrust myself to God.”

It is 1:49 a.m. and 46 sec. on Oct. 31. EgyptAir Flight 990 is cruising uneventfully at 33,000 ft. on its normal heading from New York City northeast across the Atlantic toward Cairo. At that moment, two distinct clicks of a button on the control yoke disconnect the autopilot guiding the plane. Eight seconds later, the control yoke is pushed forward, tipping the tail up, pitching the nose down, and the aircraft tilts into a precipitous but controlled dive. Fourteen seconds later, the aircraft reaches 90% of the speed of sound and zero gravity–weightlessness–as it plummets through the night sky.

The cockpit door opens again. The master alarms start to whoop. A voice demands, “What’s going on?” or “What’s happening?” Then the same voice urges, “Pull with me! Pull with me!” Twenty-seven seconds into the dive, the horizontal elevators on the tail that normally operate in tandem to stabilize the aircraft wrench in opposite directions: the left side pulls to make the plane climb, the right one pushes to keep it in a dive. Gravity and the two powerful Pratt & Whitney engines on the Boeing 767 continue to force the plane down. A second later, a small shield is flicked up over the twin-engine control levers on the central console, and both engines switch off. Four seconds after that, the plane’s speed brakes, panels deployed atop the wings rise into the airstream, disrupting the lift in an effort to slow down the descent. Suddenly, the plane begins to climb.

After an additional 11 sec., the flight-data recorder and cockpit voice recorder stop working; the altitude-reporting transponder quits. Land radar tracks the plane as it climbs 8,000 ft. with a force of gravity 2 1/2 times normal. Then the aircraft stalls, lurches downward, breaks apart and leaves nothing on the radar screen but a cascade of neon debris falling into the sea.

Those bare clicks, murmurs and whines recorded by the plane’s two black boxes, then synchronized with ground-control radar tracks, are all the “facts” investigators have so far to construct a picture of what happened to Flight 990. But do they add up to the terrible possibility that one of the pilots deliberately sent the plane into its death dive, committing an unspeakable act of self-destruction and mass murder?

In that case, despite the recording and other evidence that the pilot did not try to avert the crash, the suicide-by-crash theory still, over 15 years later, remains unproven. The National Transportation Safety Board took the hypothesis seriously from the beginning but, TIME reported, those on the Egyptian side of the investigation denied that it was a possibility.

Responding to those who interpreted the pilot’s actions as a murderous, terroristic act, many in Egypt and its allies saw a cultural presumption in the idea that a prayer in Arabic — which could also be an expression of surprise or concern — could indicate a link to terrorism. And to those who saw it as an act of personal desperation, many Egyptians said that was also an insult, given the extreme shame associated with suicide in their culture.

The pilot’s family rushed to provide evidence that the pilot, Gamil El Batouty, was a happy man with no reason to crash a plane on purpose, and officials questioned whether his recorded prayer would be interpreted in such a sinister fashion if the speaker had been Christian. For months, even as the NTSB stuck by the suicide theory, Egypt continued to press the case for alternate possibilities.

Egyptair Flight 990 and Germanwings Flight 9525 are not exactly the same situation, but they do share a few key elements. In both cases, black box recordings suggest that the person flying the plane caused and/or failed to stop the descent, and in both cases the actual wreckage will be hard to retrieve, meaning that a full review of the plane’s mechanical systems may prove impossible. But in both cases, at least so far, there is also a lack of the kind of evidence that often speaks for suicides after the fact: no note, no explicit evidence of anguish.

The lesson of the Egyptair crash, then, is that the chance is high that Germanwings investigators will never be able to say for sure what happened. The only person who could answer their questions with confidence can no longer do so.

Read next: Why the Black Box Recordings Deepen Germanwings Crash Mystery

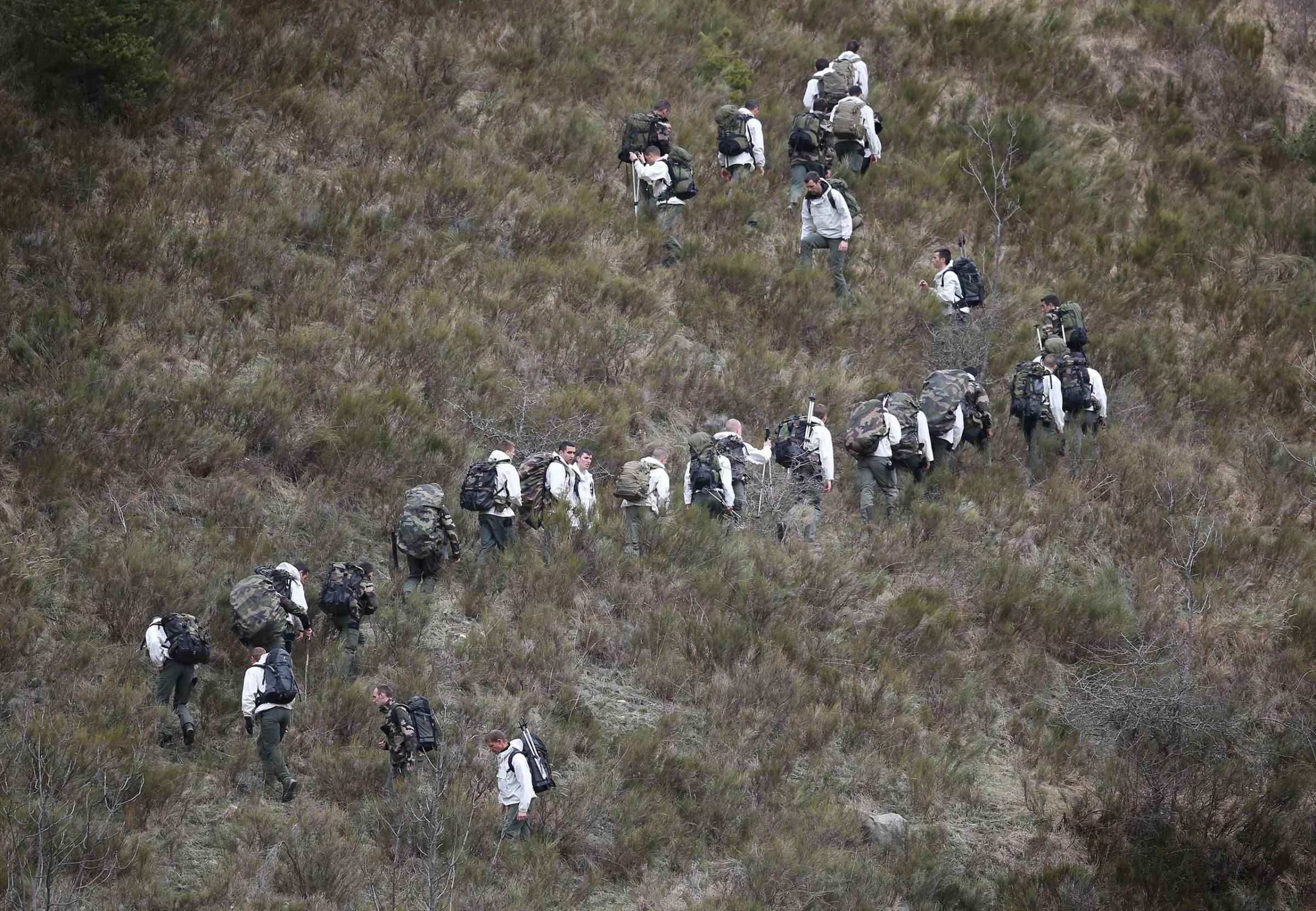

Witness Scenes From the Plane Crash in the French Alps

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com