Andreas Lubitz dreamed of flying since childhood. As a teenager in the Rheinland-Pfalz region of Germany, he joined a local flying club, first honing his skills on a glider plane and working his way up to become a co-pilot on an Airbus A320, flying for one of his country’s best-reputed carriers, Germanwings. None of his colleagues or fellow flying enthusiasts seemed to have any inkling that he could end his own life by slamming his plane into the side of a mountain in France on Tuesday, March 24, senselessly taking the lives of 149 passengers and crew members with him.

But that is the version of events that French investigators offered during a press conference on Thursday. The 28-year-old had a “deliberate desire to destroy this plane,” said prosecutor Brice Robin during a briefing in Paris. When the experienced pilot of the plane briefly left Lubitz alone in the cabin, “he voluntarily refused to open the door of the cockpit to the pilot and voluntarily began the descent of the plane,” Robin said.

The result was one of the worst tragedies in the history of European aviation, one that raises many questions about the ability of even the best airlines and flight training schools to assess the mental health of their commercial pilots.

Briefing reporters on Thursday in Frankfurt, the head of Germanwings’ parent company, Lufthansa, said he had complete faith in the competence of the company’s pilots even after this disaster. “No system in the world could prevent an event like this,” said Carsten Spohr, the chief executive of Lufthansa.

Lubitz had undergone the same rigorous tests, including physical and psychological examinations, as the rest of Lufthansa’s pilots, and he had been working as a co-pilot for Germanwings since 2013, Spohr said, with 630 hours of experience flying the A320. “He passed not only every medical test but every flight test,” he added. “He was 100% flightworthy, without a single restriction.”

According to friends of Lubitz who spoke to the media on Thursday, he was a “rather quiet” young man but gave off no signs of being depressed, let alone suicidal.

“He was happy he had the job with Germanwings and he was doing well,” a member of his local glider club, Peter Ruecker, told the Associated Press. “He gave off a good feeling.”

Before it emerged that the crash may have been intentional, the glider club released a statement on its website mourning Lubitz. “Andreas became a member of the association as a teenager, he wanted to realize his dream of flying,” the statement said. “He was able to fulfill his dream, the dream he has now so dearly paid for with his life.”

Tragically, however, the fulfillment of his dream may also have cost 149 innocent people their lives. Asked on Thursday whether Lufthansa considered the cause of the crash to be suicide, its chief executive suggested that this was too soft a word. “When one man takes 149 lives along with his own, there is word for that other than suicide,” he said.

The co-pilot’s motives, however, remain unclear. Though he reportedly had an apartment in the city of Düsseldorf, he spent much of his time at his parents’ home in the small German town of Montabaur, whose population is about 12,000. His profile on Facebook suggests innocuous tastes in the outdoors and electronic music; his photo on the sight shows him sitting in view of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge.

As the media descended on his hometown on Thursday, police established a presence around his parents’ house, while his friends expressed grief and incredulity over the his alleged decision to kill so many innocent people. “He was just another boy like so many others here,” Ruecker, his friend from the flying club, told the Reuters news agency. “Knowing Andreas, this is just inconceivable for me.”

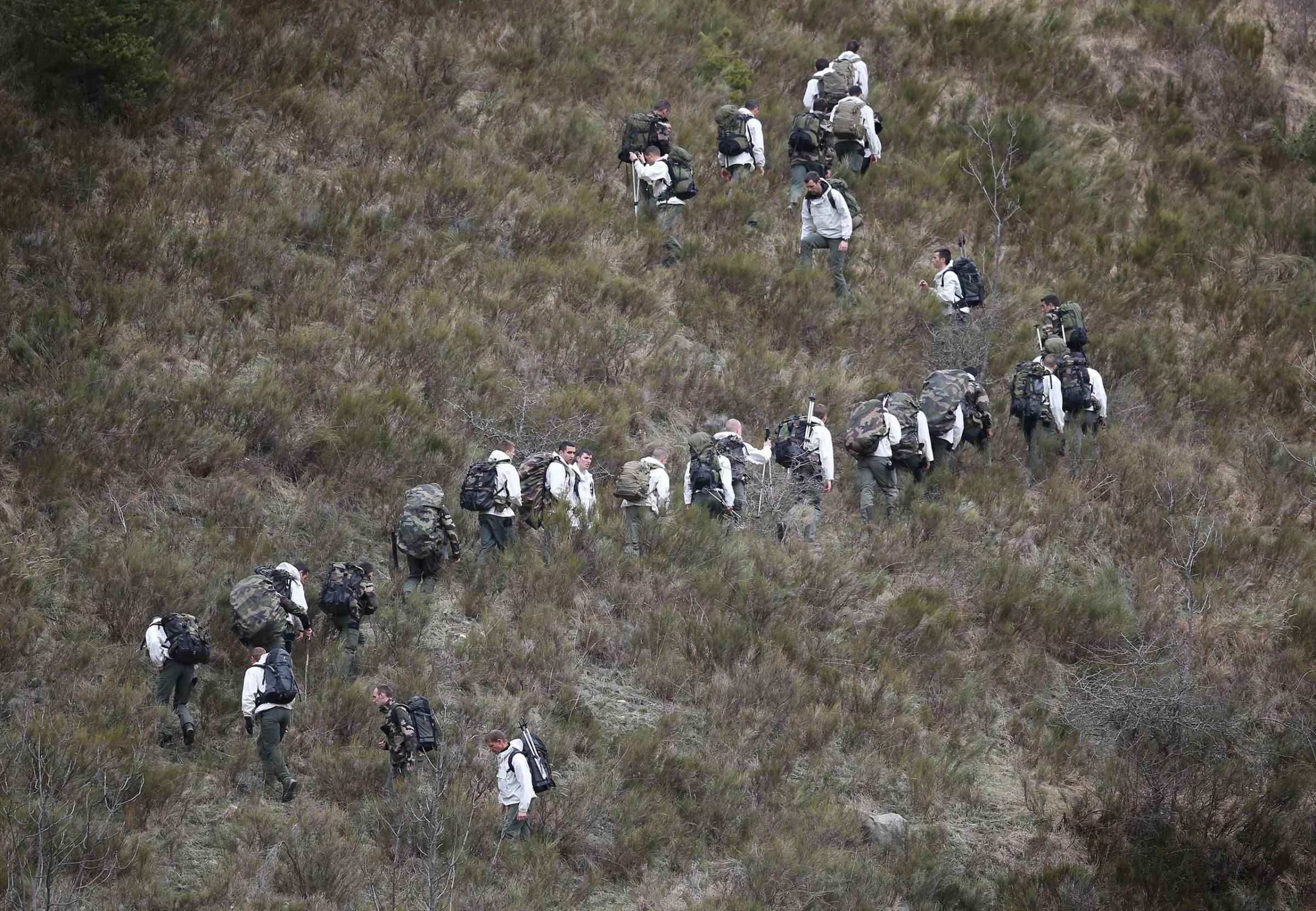

Witness Scenes From the Plane Crash in the French Alps

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com