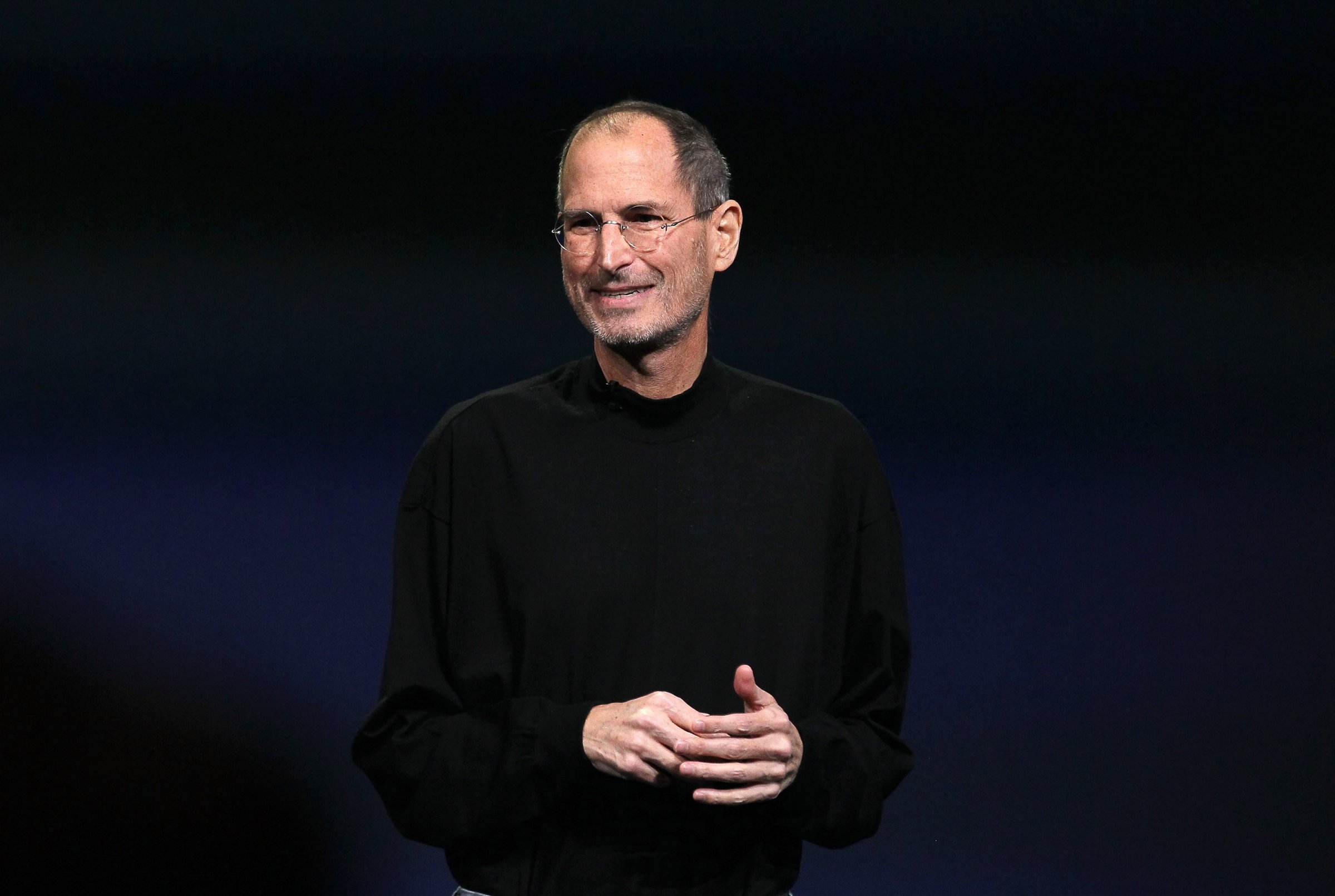

In 2011 Walter Isaacson published a biography of Apple co-founder Steve Jobs. Isaacson’s biography was fully authorized by its subject: Jobs handpicked Isaacson, who had written biographies of Benjamin Franklin and Albert Einstein. Entitled simply Steve Jobs, the book was well-reviewed and sold some 3 million copies.

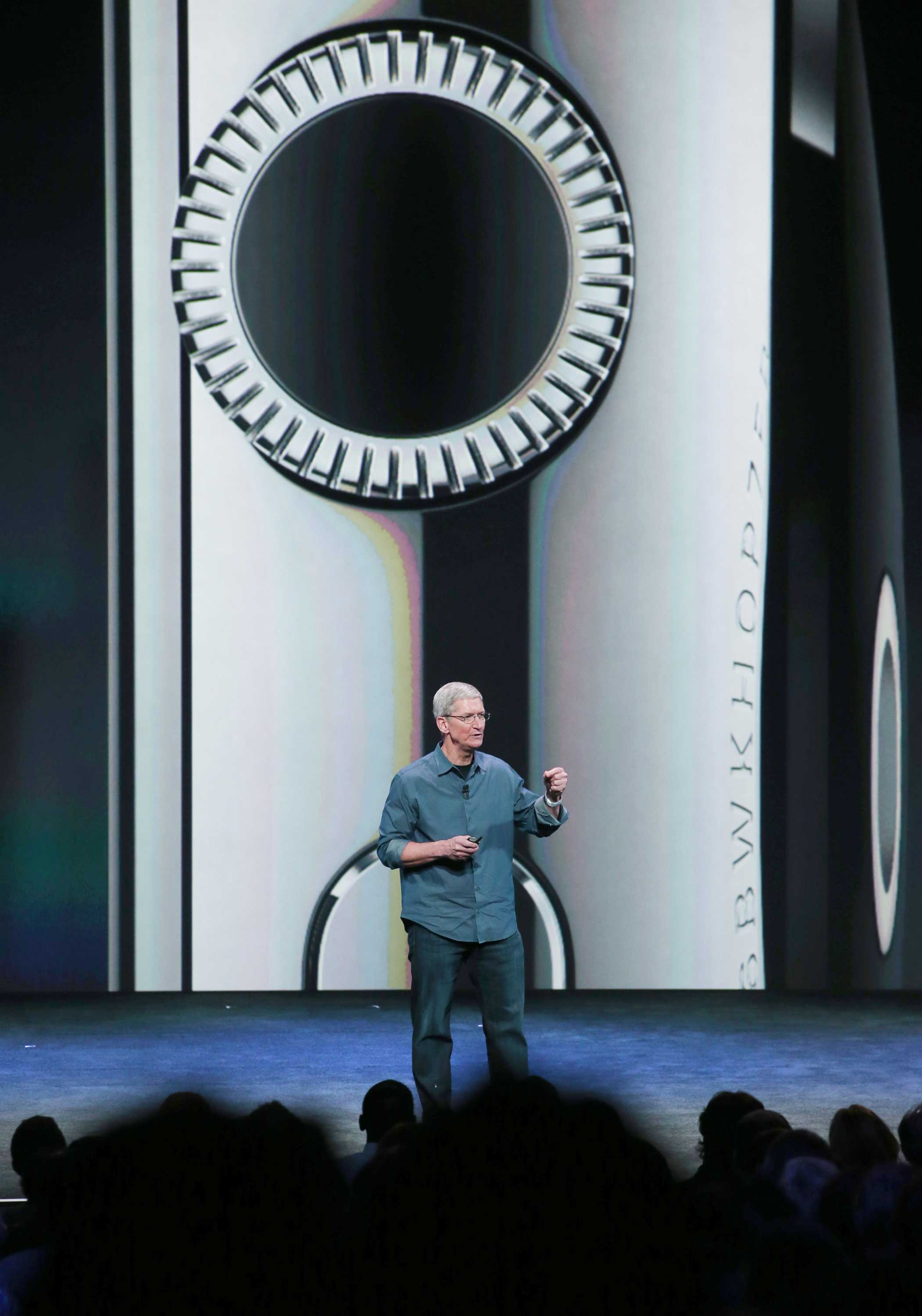

But now its account is being challenged by another book, this one called Becoming Steve Jobs, by Brent Schlender, a veteran technology journalist who was friendly with Jobs, and Rick Tetzeli, executive editor at Fast Company. Some of Jobs’ former colleagues and friends have taken sides, speaking out against the old book and praising the new one. Tim Cook, Apple’s CEO and Jobs’s successor, has said that Isaacson’s book depicts Jobs as “a greedy, selfish egomaniac.” Jony Ive, Apple’s design chief, has weighed in against it, and Eddy Cue, Apple’s vice president of software and Internet services, tweeted about the new book: “Well done and first to get it right.”

But who did get it right? And why do people care so much anyway?

(This article comes with a bouquet of disclosures, starting with the fact that Isaacson is a current contributor and former editor of TIME magazine and as such my former boss. I’m quoted in his biography—I interviewed Jobs half a dozen times in the mid-2000s, though he and I weren’t friendly. Schlender spent more than 20 years writing for Fortune, which is owned by TIME’s parent company, Time Inc., and Tetzeli was an editor both at Fortune and at Entertainment Weekly, also a Time Inc. magazine.)

Schlender and Tetzeli have given their book the subtitle “The Evolution of a Reckless Upstart into a Visionary Leader,” and its emphasis is on the transformation that Jobs underwent between 1985, when he was ousted from Apple, and 1997, when he returned to it. “The most basic question about Steve’s career is this,” they write. “How could the man who had been such an inconsistent, inconsiderate, rash, and wrongheaded businessman … become the venerated CEO who revived Apple and created a whole new set of culture-defining products?” It’s an excellent question.

11 Amazing Features of the Apple Watch

Becoming Steve Jobs is, like most books about Jobs, tough on his early years. He could be a callous person (he initially denied being the father of his first child) and a terrible manager (the original Macintosh, while magnificent in its conception, was only barely viable as a product). On this score Schlender and Tetzeli are clear and even-handed. It’s easy to forget that Jobs originally wanted Pixar, the animation firm he took over from George Lucas in 1986, to focus on selling its graphics technology rather than making movies, and if the geniuses there hadn’t been more independent he might have run it into the ground.

Schlender and Tetzeli argue that it was this middle period that made Jobs. The failure of his first post-Apple company, NeXT, chastened him; his work with Pixar’s Ed Catmull and John Lasseter taught him patience and management skills; and his marriage to Laurene Powell Jobs deepened him emotionally. In those wilderness years he learned discipline and (some) humility and how to iterate and improve a project gradually. Thus reforged, he returned to Apple and led it back from near bankruptcy to become the most valuable company in the world.

Schlender and Tetzeli strenuously insist that they’re upending the “common myths” about Jobs. But they’re not specific about who exactly believes these myths, and in fact it’s a bit of a straw man: there’s not much in Becoming Steve Jobs that Isaacson or anybody else would disagree with. What’s missing is more problematic: as it goes on, Becoming Steve Jobs gradually abandons its critical distance and becomes a paean to the greatness of Jobs and Apple. Jobs was “someone who preferred creating machines that delighted real people,” and his reborn Apple was “a company that could once again make insanely great computing machines for you and me.” It reprints the famous “Think Different” spiel in full. It compares Jobs’ career arc, without irony, to that of Buzz Lightyear in Toy Story. It unspools sentences like: “Steve [we’re on a first-name basis with him] also understood that the personal satisfaction of accomplishing something insanely great was the best motivation of all for a group as talented as his.”

Read More: Apple’s Watch Will Make People and Computers More Intimate

It’s easy to see why Apple executives have endorsed Becoming Steve Jobs, but it has imperfections that would have irked Jobs himself. The writing is slack—it’s larded with clichés (“he wanted to play their game, but by his own rules”) and marred by small infelicities (it confuses jibe and gibe, twice). It lacks detail: for example, it covers Jobs’ courtship of and marriage to Laurene in two dry pages (“Their relationship burned intensely from the beginning, as you might expect from the pairing of two such strong-willed individuals”). By contrast, a Fortune interview Schlender did with Jobs and Bill Gates in 1991 gets 13 pages. Whatever its faults, Isaacson’s book at least dug up the telling details: in his account of the marriage we learn that Jobs was still agonizing over an ex-girlfriend; that he had a hilariously abortive bachelor party; that he threw out the calligrapher who was hired to do the wedding invitations (“I can’t look at her stuff. It’s shit”); and that the vegan wedding cake was borderline inedible.

Jobs was famously unintrospective, but Schlender and Tetzeli seem almost as incurious about his inner life as he supposedly was. Jobs’ birth parents were 23 when they conceived him, then they gave him up for adoption; when he was 23 Jobs abandoned his own first child. It takes a determinedly uninterested biographer not to connect those dots, or at least explain why they shouldn’t be connected. We hear a lot about what Jobs did, and some about how he did it, but very little about why.

Jobs was a man of towering contradictions: he identified deeply with the counterculture but spent his life in corporate boardrooms amassing billions; he made beautiful products that ostensibly enabled individual creativity but in their architecture expressed a deep-seated need for central control. Maybe making educated guesses about a major figure’s private life is unseemly, or quixotic, but that’s the game a biographer is in. Ultimately there’s no point in comparing Steve Jobs and Becoming Steve Jobs, because the latter book isn’t really a biography at all, much less a definitive one.

A more interesting question might be, why has the story of Steve Jobs become so important to us? And why is it such contested territory? He’s also the subject of a scathing new documentary by Alex Gibney and an upcoming biopic written by Aaron Sorkin. Was Jobs, to use Schlender and Tetzeli’s terminology, an asshole, or a genius, or some mysterious fusion of the two? It’s as if Jobs’ life has become a kind of totem, a symbolic story through which we’re trying to understand and work through our own ambivalence about the technology he and his colleagues made, which has so thoroughly invaded and transformed our lives in the past 20 years, for good and/or ill. Apple’s products are so glossy and beautiful and impenetrable that it’s difficult to do anything but admire them. But about Jobs, at least, we can think different.

Read next: Becoming Steve Jobs Shares Jobs’ Human Side

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com