A backlash against a Batgirl comic book cover some perceived as sexually violent has caused the cover to be withdrawn — leading to a backlash against perceived censorship. Sexism in popular culture is a valid concern. But when feminist criticism becomes an outrage machine that chills creative expression, it’s bad for feminism and bad for female representation. Making artists, writers, filmmakers, and even audiences walk on eggshells for fear of committing thoughtcrime against womanhood is no way to encourage quality art or enjoyable entertainment — not to mention the creation of good female characters.

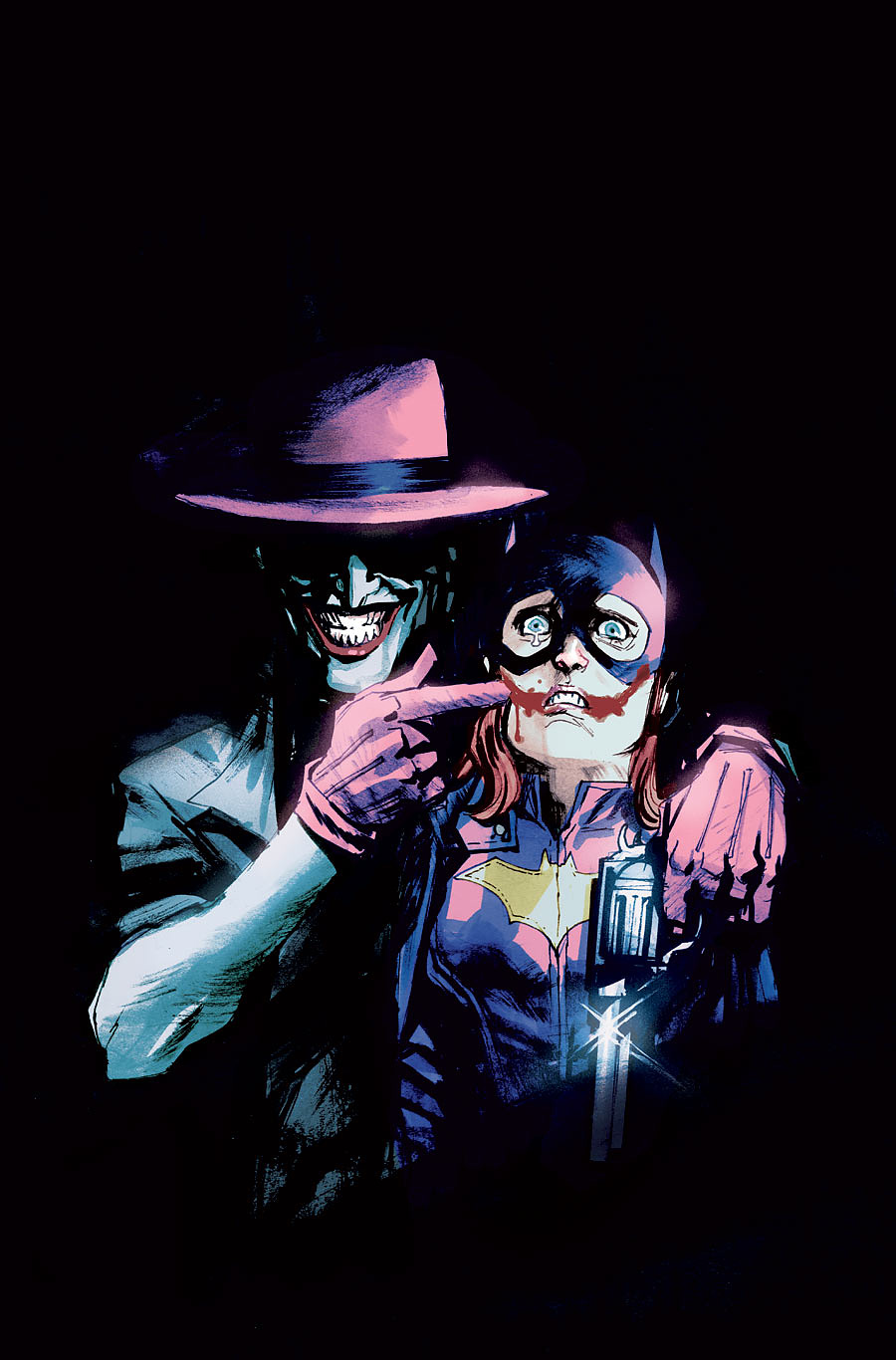

The controversial artwork, by Rafael Albuquerque, showed Joker smearing a bloody grin on Batgirl’s frightened face, his arm draped over her shoulder with a gun in his hand. This was an upcoming variant cover for an issue of the Batgirl comic, part of a series of Joker-themed comic covers for the iconic villain’s 75th anniversary. It was also an homage to The Killing Joke, a 1988 graphic novel in which Batgirl/Barbara Gordon is shot by the Joker (and stripped while unconscious) in a plot to drive her father, Police Commissioner Jim Gordon, insane.

An online preview set off an angry reaction and generated a hashtag, #ChangeTheCover. Some objected to the image of Batgirl as a helpless victim; others slammed DC Comics for “glamorizing sexual assault.” (Many fans believe Barbara was raped by Joker in The Killing Joke, though the comic itself makes no reference to rape.) DC Comics and Albuquerque promptly announced that the cover was being pulled at the artist’s request.

While this is not “censorship,” Albuquerque’s choice was clearly made under pressure; his statement leaves no doubt that it was a painful decision. The cancellation has been defended on the grounds that the dark, grotesque cover does not match the upbeat tone of the new Batgirl comic books and is wrong for their target audience. Yet the Joker cover was a variant, not the standard version of the comic book issue; it would not have been foisted on any unwilling readers, only made available to customers who would have wanted it — mainly collectors and Joker fans. They no longer have that option.

Feminist culture critic Noah Berlatsky argues that the controversy reflects the changing, more female audience for comic books. But female fans are not a monolith. Some women have praised the cover, even insisting that it contains an inspirational message of survival and triumph: Comic book readers know the crippled Batgirl returns as Oracle, a hero with genius-level computer skills who is no longer a sidekick but Batman’s equal.

Berlatsky sees the disputed cover as the legacy of an era when women’s place in comic books was to provide “sexualized cannon fodder.” But that’s unfair to the cover, in which Batgirl isn’t particularly sexualized, and to comic books, which even in the pre-feminist past gave characters such as Batgirl, Catwoman, or Wonder Woman some opportunities for heroics and adventures of their own (though, admittedly, often treating them as inferior to male heroes). As for the present, the feminist pop culture website The Mary Sue cites several Joker-themed comic-book covers that feature strong-looking heroines. This is meant to show that the variant Batgirl cover could have been similar; however, one can just as easily conclude that women in comic books are faring quite well and won’t be demeaned by one edgy cover.

Indeed, objections to supposedly sexist cruelty toward female characters can look like a sexist plea for special protection for women — given how often male comic-book characters are subjected to shocking abuse. In The Killing Joke itself, Commissioner Gordon is stripped naked and chained to an amusement-park ride while forced to watch giant images of his wounded daughter. One storyline in which the Joker temporarily gained the power to shape reality had Batman being tortured, killed, and resurrected by his enemy day after day.

While critics of the Batgirl cover have argued that Batman and other male heroes would never be shown so powerless, others have readily found examples of such depictions — including one in which Batman is helpless at the hands of a female villain. Male heroes in peril may be far less likely to look fearful or distressed; but one may ask, as does Canadian entertainment journalist Liana Kerzner, if the answer is to expand the men’s range of allowed emotions rather than limit the range allowed for women.

Ultimately, what’s demeaning to women in fictional portrayals is often a matter of opinion. For instance, Batman soon recovered from a broken back while Batgirl remained a paraplegic for more than 20 years, until a recent relaunch. To some, this is a classic example of how female heroes are disempowered. To others, the fact that the disabled Barbara/Oracle managed to be an active crime-fighter using only her upper body — and her intelligence — made her not only more human but more heroic. Comic book writer Gail Simone, a strong critic of sexism in comic books, has said that she repeatedly fought against restoring Batgirl’s full mobility because of her inspirational value to people with disabilities.

Likewise, a strong and overtly sexual female character could be seen as pandering to the “male gaze” or as promoting female empowerment. Bayonetta, a videogame featuring a deliberately hypersexualized female super-fighter, has been denounced as sexist and exploitative by some feminists including media critic Anita Sarkeesian. On the other hand, feminist blogger Alyssa Rosenberg has published a guest post praising the game and its heroine, who “plows through the patriarchy like a wrecking ball” while having fun and flaunting her sexuality.

The worst message to send creators is that if your female character doesn’t get a Good Feminist seal of approval — if she shows too much weakness or too much sexuality, if she has too many stereotypical female qualities or too many “male” ones, if she suffers a failure or a harrowing ordeal, if she is shown in an overly disturbing situation — your work may be attacked as anti-woman. That’s a prescription for bland characters and dull stories.

Feminist critics make a strong case when they assert that there are still not enough female protagonists or major characters in popular culture and not enough good female-driven stories. The answer is to spend less energy on policing and more on creating. More women, fewer litmus tests.

Read next: The New Recipe for Women Entrepreneurs to Find Success

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com