Industrialist, record-setting aviator, movie mogul, recluse — Howard Hughes was one of the most accomplished and mysterious figures America has ever produced . . . and, in the end, one of the most pitiable.

An almost preposterously wealthy and dashing figure of the 1930s, Hughes was an engineering prodigy who, even as a young boy growing up in Texas, pushed the proverbial envelope. In 1916, when he was 11, he built the first radio transmitter ever used in Houston. He was forever tinkering with engines and electrical devices, re-designing and making them more efficient, more powerful, more useful, better.

By the time he was in his early 20s, he had discovered another lucrative talent, and was living the high life in Los Angeles, producing movies. And in everything he did, whether backing films or flying and engineering fast (and faster, and faster) planes, Hughes was a hands-on kind of guy.

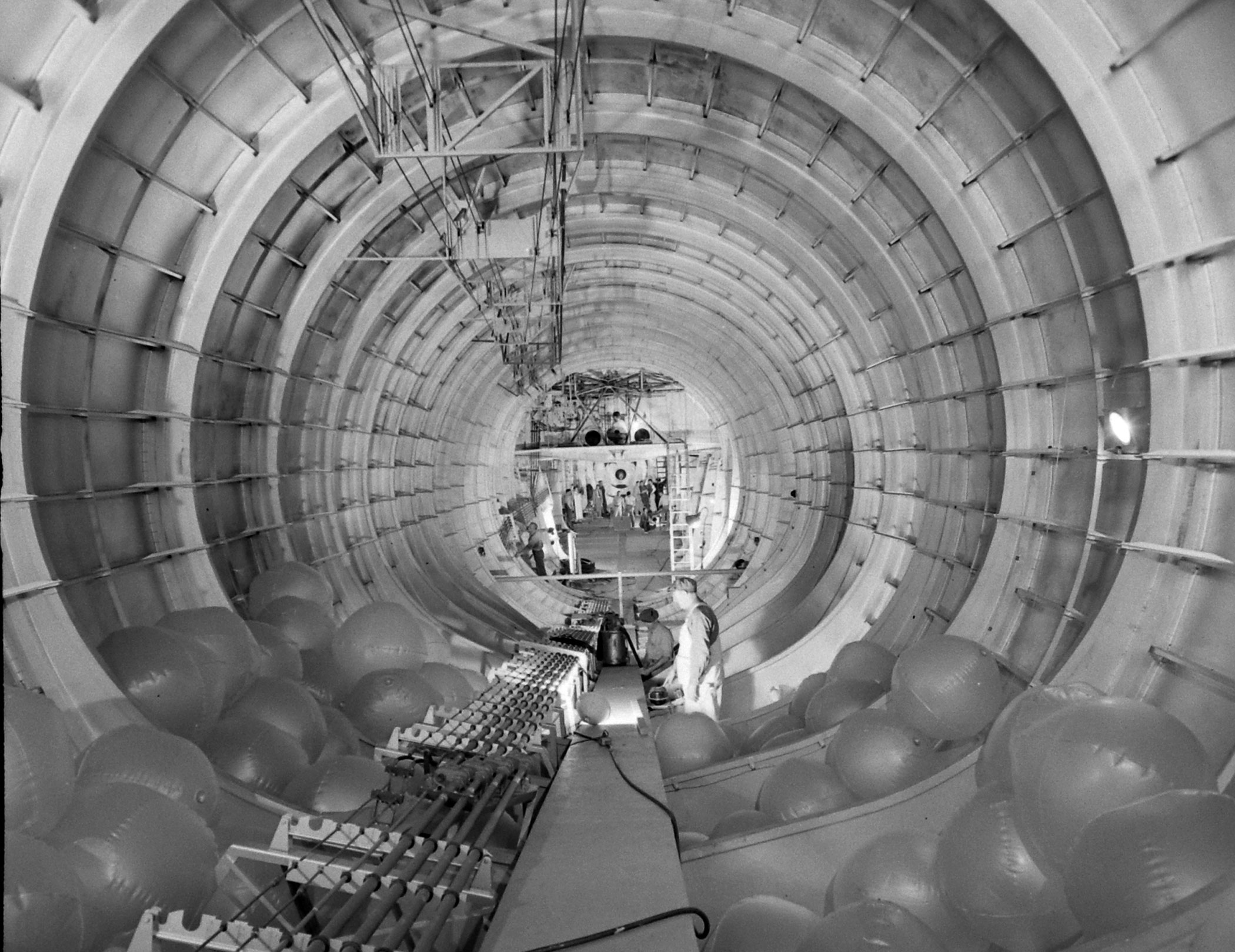

When contracted by the U.S. government in the mid-1940s to build a military transport plane, he responded in his usual modest style and set about creating the H-4 Hercules, a massive wooden plane later famously dubbed the “Spruce Goose” which would, when completed, be the largest flying machine ever built. (The plane was actually made of birch, not spruce: the contract required that the aircraft be built of “non-strategic materials” during the war. But the catchy nickname — which Hughes always hated — stuck.)

Despite its enormous size, the Hercules was meant to be flown with a crew of only three people. Its planned “cargo,” meanwhile, was beyond impressive: up to 750 fully equipped military troops, or one 35-ton M4 Sherman tank.

“I want to be remembered for only one thing,” the billionaire once said, “and that’s my contribution to aviation.”

Before long, however, his contributions — as well as his integrity and his honesty — would be severely questioned by elected officials who never had much use for the flamboyant Hughes. In 1947, for example, he was compelled to testify before a Senate committee led by Sen. Owen Brewster (R-Maine). Brewster effectively accused Hughes — at the time, the head of TWA, in addition to his myriad other projects and businesses — of misusing $40 million in government funds during the development of two planes: the Hughes Aircraft XF-11 and the H-4 (the Spruce Goose), neither of which was ever successfully delivered to the government.

During the hearings, which ended inconclusively, Hughes stirringly defended his work on the H-4, in particular:

“The Hercules was a monumental undertaking,” he testified. “It is the largest aircraft ever built . . . I put the sweat of my life into this thing. I have my reputation rolled up in it and I have stated several times that if it’s a failure I’ll probably leave this country and never come back. And I mean it.”

Brewster claimed that the H-4 was a classic and disgraceful boondoggle and would never, ever fly. On November 2, 1947, for a few minutes at least, Hughes famously proved him wrong. With co-pilot Dave Grant and assorted engineers and mechanics, Hughes flew the monumental plane (its wingspan of 320 feet remains the largest in history) for about a mile, roughly 70 feet above Long Beach Harbor. The plane never flew again — but Hughes felt vindicated.

All the controversy and political palaver around the plane’s construction, meanwhile, obscured something about the H-4 that, to this day, is often overlooked in any discussion of the mammoth aircraft: namely, its sheer, sleek aesthetic power. Putting aside for a moment the technical complexities and challenges inherent in designing a flying vessel the size of the Hercules, one can do a lot worse than focus on the beauty of the thing. As an object, the Hercules looks like something Brancusi might sculpt — if the great Romanian artist dabbled in aeronautics and wished to create a work 220 feet long, 25 feet high and 30 feet wide.

Here, LIFE.com offers a series of photos — many of which never ran in LIFE — of the largest “flying boat” ever built and the aviation genius who designed and flew her.

As the years passed, Hughes retreated deeper into a severe obsessive-compulsive disorder, drug abuse and the debilitating, deadening isolation for which he later became so famous. By the time of his lonely death in April 1976, he had devolved from a rakish, even debonair man of the world into a skeletal wreck. Postmortem x-rays revealed hypodermic needles (likely used to inject codeine, to help manage his chronic pain) embedded in Hughes’ arms. His six-foot, four-inch frame weighed roughly 90 pounds. His hair and nails had grown freakishly long. He was wholly and frighteningly unrecognizable. He was 70 years old.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com