That I’m nowhere near finished with Bloodborne says as much about From Software’s PlayStation 4 lycanthrope-mauler as anything. I’ve had the game since late last week and clocked at least 40 hours through Monday night — just shy of what some claim it takes to beat the game. I’m still working through the first few areas. Chalk my sluggishness up to being a slower, more methodical player.

But it’s also because Bloodborne carries forward the Souls’ series back-breaking pedigree: this is a game about pushing the proverbial ball up something more like a mountain, millimeter by grueling millimeter, looking for meaningful perspective on your progress. From Software’s great triumph as a studio — and Bloodborne epitomizes this — is in making that feel like something you want to do, not that you have to.

Here’s what I think of Bloodborne so far, absent the multiplayer angle, which I’m waiting to futz with until the game’s launch tomorrow, March 23.

The new “regain” system changes everything

From Software’s entire developmental oeuvre trades on simplistic sounding gameplay ideas that wind up having monumental depth. To wit, in Bloodborne the studio’s added what it calls a “regain” system to combat.

It sounds trivial: after an enemy damages you, you have a few crucial seconds to strike back and, if you connect without taking further damage, replenish your flagging health bar. They hit, you hit. On paper, it’s as nuanced as a pugilism seminar.

But Bloodborne packs its Grand Guignol zoo with deft, spontaneous enemies who make it incredibly difficult to land reciprocal blows before the regain timer runs out and the damage to your health bar becomes permanent. Regain is thus another dare (in a game about daring), goading you to act recklessly, to make split-second tactical choices that, if you’re not thoroughly versed in an enemy’s attack patterns, often result in your taking even more damage.

Multiply by the barrage of new enemy types, each with unique attacks, and how you dispatch them — the crux of these games, requiring methodical thought — is easily the most nuanced of any of the prior Souls installments.

So does the game’s loot-hunt twist

The Souls games are basically risk-reward abattoirs wrapped around hack-and-slash chutes. You haul around souls (the games’ version of cash), but drop them if you die, after which you have just one shot to bash your way back to the spot you croaked and reclaim your booty. Die before you get there, and those dropped goods vanish forever, forfeiting all your hard work to that point.

Bloodborne continues in the same vein (instead of souls, it calls your cha-chings from enemy kills “blood echoes”), but with a fascinating wrinkle: now, if you die in the vicinity of enemies, they can snatch up your lost treasure and go for a stroll.

Return to the spot of your demise, and you’ll often find it bare. Instead, you have to scan nearby enemies until you identify one with glowing eyes — the telltale sign it’s the creature schlepping your goods. And the only way to retrieve them is to defeat the creature in combat. Suffice to say I’ve lost a lot of hard-earned moola overzealously rushing blood echoes thieves flanked by lethal helpers. (Woe to anyone who loses their trove in battle with a deadly mini-boss, and has to fight it to get their blood echoes back.)

It’s all about crowd control

The Souls games generally involve engaging enemies one and sometimes two at a time. Bloodborne by contrast opens the battlefield up to whole squadrons of horrors, each creature bristling with different weapons, hit ranges and attack sequencing, making them pretty much phalanxes of anarchic insanity.

Figuring out how to break down a crowd, maybe by luring away one or two enemies at a time (you can toss pebbles, Shadow of Mordor-like), is thus as crucial as leveraging the game’s new arsenal of crowd control weapons. If you’re into observation-related strategizing, and I am, Bloodborne forces you to pause and study groups of enemies before engaging them far more than in From Software’s prior games.

You can scan enemies from a distance — and you’ll need to

Demon’s Souls and both of the Dark Souls games opened on vast panoramas, but blurred their beautifully bleak far-off scenery for technical reasons. Bloodborne makes no such compromises, spotlighting ever exquisite distant detail of its Boschian nightmare-scapes, allowing you to eyeball enemy mobs (and their shambling trajectories) from several stories up, so you can plot your approach vectors accordingly.

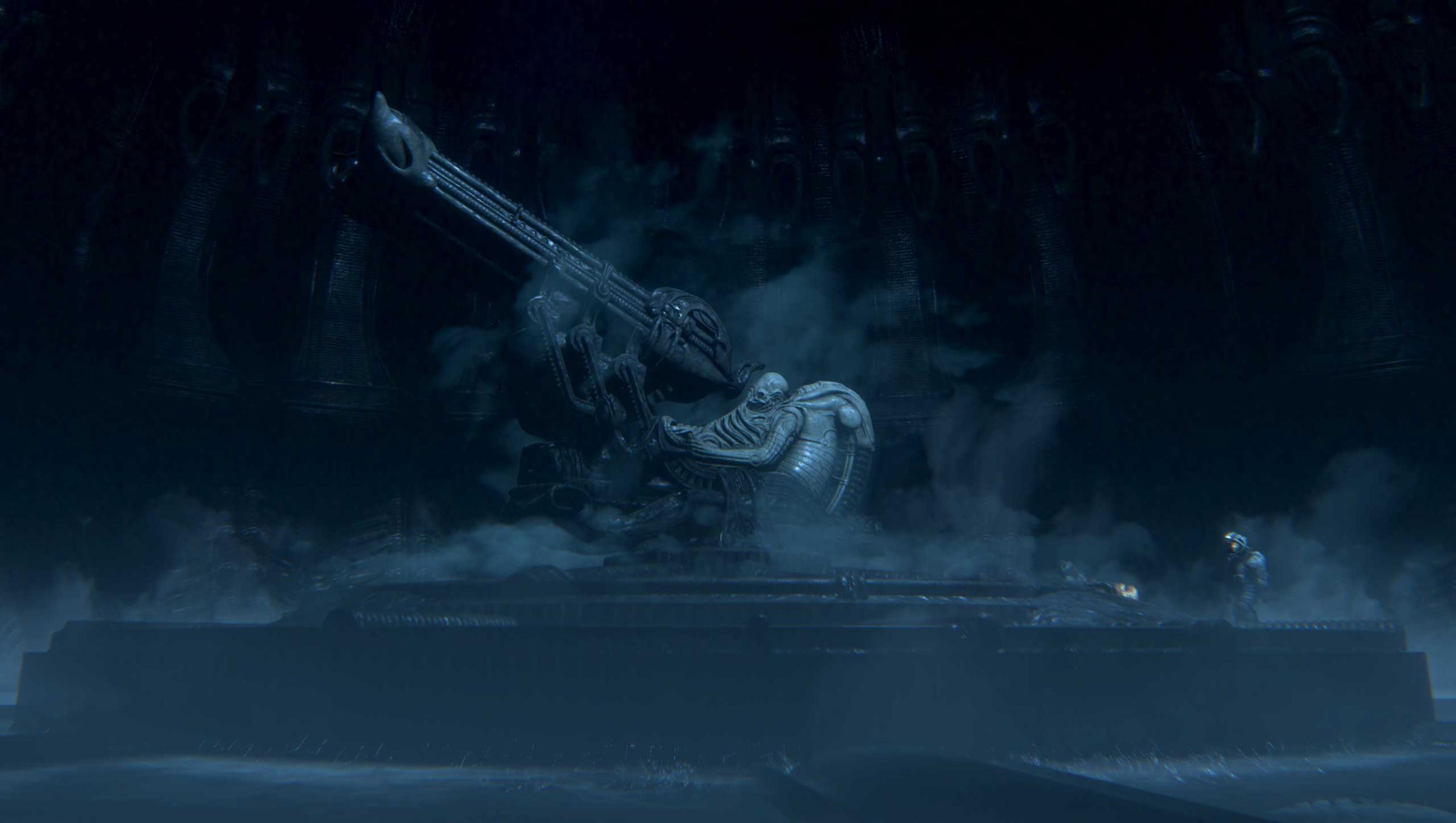

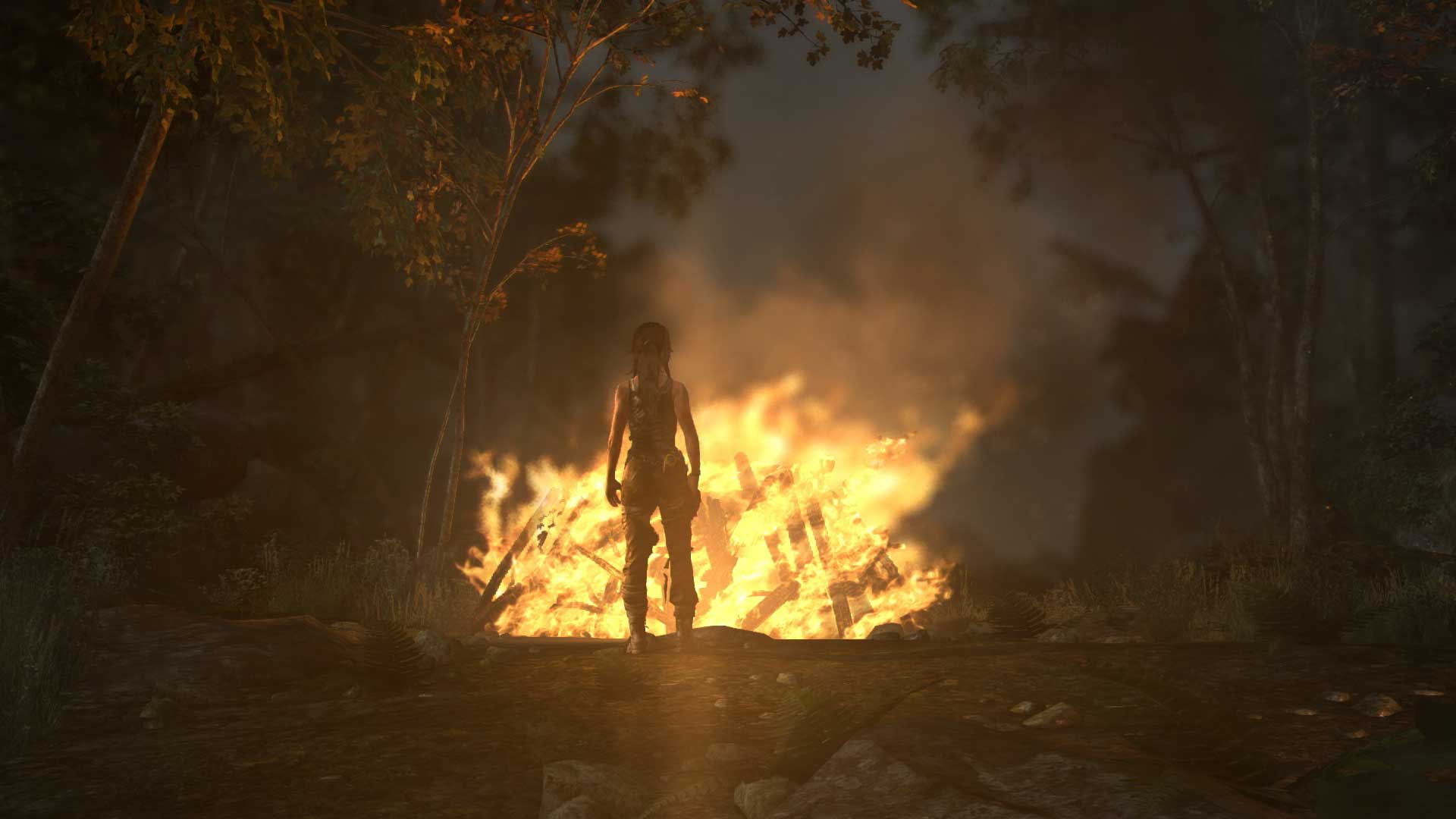

It’s the apotheosis of From Software’s ultra-creepy visual aesthetic

I’ve loved the bleak, convoluted, almost Peake-ian feel of the Souls games for years, but Bloodborne ratchets that up another order of magnitude. In the starter areas, you’ll prowl gorgeously macabre coffin-choked cobblestone streets, observing flamboyant gothic tableaus framed by cathedral structures with coruscating stained glass windows and knuckled spires, while a fat, apocalyptic star baptizes the landscape like something out of a Jack Vance yarn.

I imagine you’re going to see the adjective “Lovecraftian” slung around a lot here, and fair enough, since he’s clearly an influence. But after reading Jeff Vandermeer’s hypnotically weird Southern Reach trilogy last year (if you’ve read it, I’m thinking specifically of the tunnel/Crawler sequences), I have a new word to describe how these games work on me: Vandermeerian.

Access points are just access points (again)

Dispensing with Dark Souls’ “campfires-make-it-all-better” approach to vitality replenishment, where you could heal by tagging the nearest bonfire, Bloodborne’s lantern-lit checkpoints are simply I/O ports to and from the game’s safe hub (that is, they’re more like Demon’s Souls’ bonfires). If you want to heal, you instead have to quaff blood flasks swiped from defeated enemies.

The only problem: so far, those blood flasks are pretty easy to come by. You can carry up to 20 on your person off the bat, and store another 100 in the safe hub (they’re a lucrative business, too: I’ve probably sold half as many as I’ve gulped). I have yet to run short of flasks during the toughest boss battles, where when I’ve died, it’s because I didn’t drink them fast enough.

And the levels cross-connect in fascinating ways

I’m not sure we’ll ever see an open-world From Software game (or that we’d even want to), nor is Bloodborne in so much as the same hemisphere as those sorts of games. But the levels I’ve plumbed are far more intertwined, and in cleverly concealed ways, offering, among other things, the option to take on certain bosses out of sequence. If you enjoy hunting for secret avenues or byways, some that lead to secret items, others that open up shortcuts or ways of cutting ahead, Bloodborne is flush with them.

But some of the boss fights are too pattern-enslaved

Maybe this changes further along, but all the end-area creatures I’ve battled have been tediously bipolar: you’re either destroyed quickly for lack of pattern recognition, or winning almost effortlessly once you’ve sussed the latter.

The most interesting thing about Bloodborne (so far, for me) is the crowd-control dynamic that coalesces spontaneously in the midst of a level, defying rote approaches. The boss fights, by contrast, come off too much like the same old static puzzles: once you’ve solved for X, you’re just going through the motions.

It really is Dark Souls with shotguns (but they’re not the main attraction)

That’s what a Sony community manager called it. It sounds glib, but only because it misses Bloodborne’s real star: its transformable arsenal of melee weapons. Brandish the game’s cane, for instance, and you’ll execute a series of fast, nominally damaging hits at short range. But pull one of the gamepad’s triggers and, after rapping the cane on the cobblestones (transformations aren’t instantaneous), it’ll change into something Castlevania’s Simon Belmont would appreciate: a jangling whip that, while slower to strike, deals pain at much greater range and lets you tag entire swathes of enemies.

Projectile weapons, by contrast, are more adjuncts to your melee armory, used offhand to stun or drive back enemies before you launch the coup de grace from your main hand. They’re helpful, in other words, but only as blowback tools. There’s no ballistic finesse involved, and since the main action’s happening in your other hand, that’s as it should be.

The chalice dungeons are kind of boring

The idea with chalice dungeons is that you stumble on goblets in the main game, then perform a “chalice ritual” in the game’s safe zone to spawn mini-dungeons from random seeds, which you can then visit at leisure to practice or level up. Each time you perform the ritual, the layout of the dungeons — including creature placement, trap arrangements and boss finales — gets rejiggered.

Random generated dungeons are already dull by design, but here they feel doubly so. After slogging through Bloodborne’s handcrafted main levels hundreds (and eventually thousands) of times, who wants to plow through haphazardly computer-built ones?

As an alternative to grinding out the same choreographed battle maneuvers in the primary areas to level up, introducing optional mini-dungeons isn’t a terrible idea. And the way the game mashes up enemy types and difficulty levels makes for a curiously asymmetric (and in that sense, unique) experience. But so far, they’re too arbitrary to hold my interest, though perhaps that’ll change once I’ve had a chance to try them in cooperative or player-vs.-player modes.

See The 15 Best Video Game Graphics of 2014

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com