Anyone learning about Islam from the headlines alone might think it was a faith powered by violence, inflexible laws, and sexism. In Nigeria, the extremists of Boko Haram kidnap schoolgirls to use as sex slaves and suicide bombers. A manifesto distributed by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) allows girls to marry at age nine and states that women should work outside the house only in “exceptional circumstances.” It’s not only extremist movements that treat women as second-class citizens, but also Western allies in the fight against them. Whether it’s Saudi Arabia, where women are banned from driving, or Egypt, where a husband can divorce his spouse without grounds or going to court, options denied to his wife, most Muslim countries run on the premise that men have a God-given authority over women.

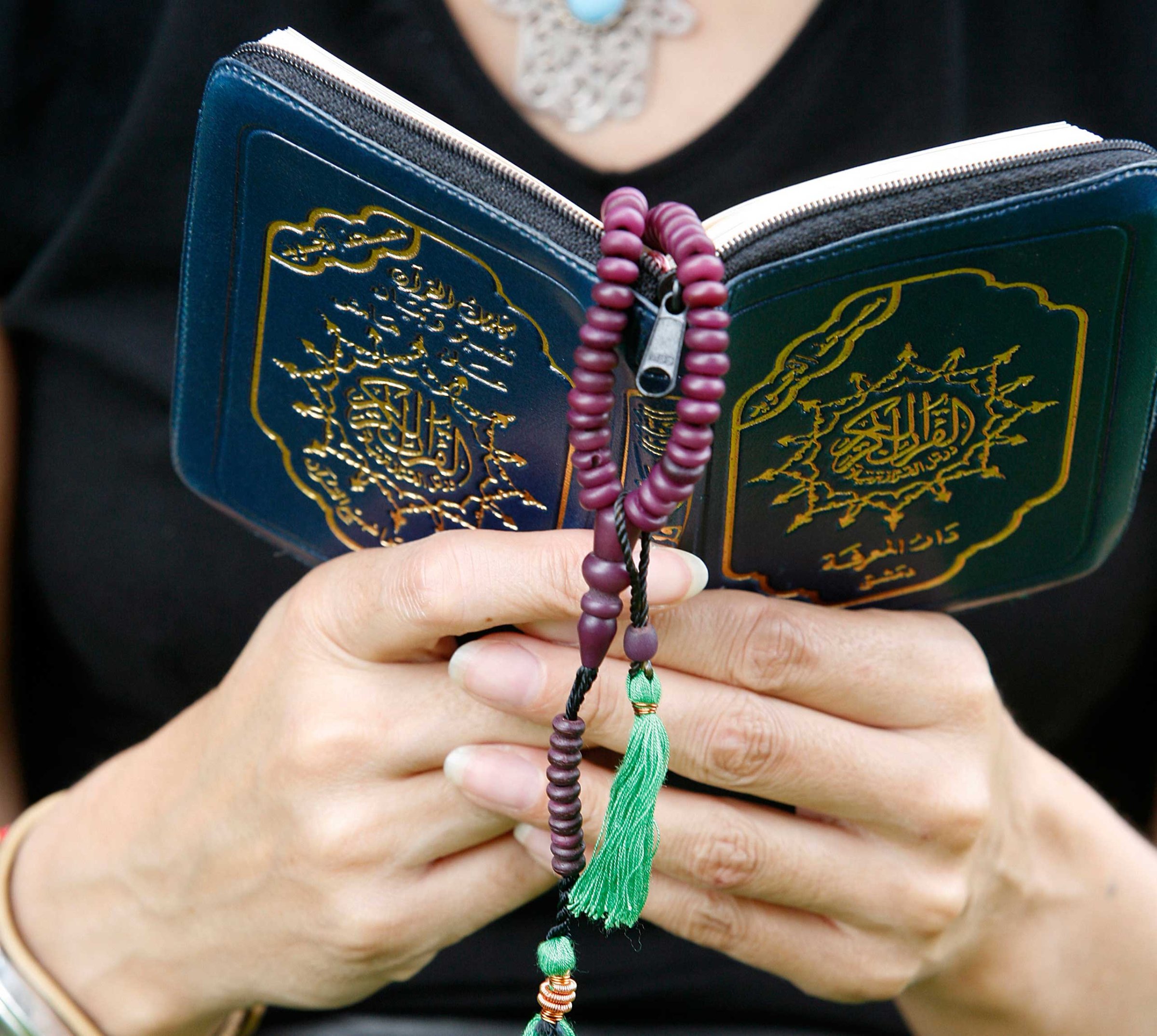

But Muslim women are fighting back. While despotic governments and extremists battle for power, Islamic scholars, community activists, and ordinary Muslims are waging a peaceful jihad on male authority, demanding what they say are God- given rights to gender equality and justice.

From Cambridge to Cairo to Jakarta, women are going back to Islam’s classical texts and questioning the way men have read them for centuries. In the Middle East, activists are contesting outdated family laws based on Islamic jurisprudence, which give men the power in marriages, divorces, and custody issues. In Europe and the United States, women are chipping away at the customs that have had a chilling effect on women praying in mosques or holding leadership positions. This winter, the first women-only mosque opened in Los Angeles.

These efforts are localized and diverse. But all are part of the multi-faceted struggle in today’s Islamic world between fundamentalist rigidity and a pluralist, inclusive faith. “We represent hope, hope for the future, and for what it means to be Muslim today,” said Zainah Anwar, director of the global Muslim women’s organization Musawah—Arabic for ‘equality’—at a recent conference in London. “Do we want to choose ISIS? Or do we want to choose musawah?”

Anwar was addressing a packed auditorium at the University of London’s School of Oriental and Asiatic Studies for the release of a powerful new weapon for Islamic gender warriors: a book examining how a single verse in the Quran became the basis for laws across the Islamic world asserting Muslim men’s authority—and even superiority—over women. In Men in Charge?, scholars tackle what Musawah has dubbed “the DNA of patriarchy” in Islamic law and custom: the thirty-fourth verse in the fourth chapter of the Quran, among the most hotly debated in the Islamic scripture. The English translations of the verse vary, but one popular one conveys the mainstream takeaway: “Men are in charge of women, because Allah hath made the one of them to excel the other, and because they spend their property [for the support of women.]”

For centuries, male jurists have cited 4:34 as the reason men have control over their wives and the female members of their family. When a wife doesn’t want to have sex, but feels she should submit to her husband, this sense of duty derives from the concept of qiwamah—male authority—derived from Verse 4:34. When a Nigerian wife reluctantly has to agree to her husband taking a second or third wife, this is qiwamah in action, notes the book. The concept of qiwamah “is one of the most flagrant misconceptions to have shaped the Muslim mind over the centuries,” Moroccan Islamic scholar Asma Lamrabet writes. “It assumes that the Quran has definitively decreed the absolute authority of the husband over his wife, and for some, the authority of men over all women.”

While the overall message of the Quran is unchanging, say Muslim reformers, new generations must find their own readings of the sacred texts. As it stands, Islamic fiqh, or jurisprudence, was largely forged during the medieval period, when women’s roles and the concept of marriage and male authority were very different. Why, they ask, should the way that 10th-century Baghdadi men read the Quran dictate the rights of a 21st-century woman? To the reactionaries who charge that these reformers are deviating from Islam, Islamic feminists point out that there is a difference between Islamic jurisprudence—a man-made legal scaffolding developed for the specific conditions of medieval Muslim life—and the divine law itself, which is eternal, unchanging and calls for justice. It’s not the Quran they question, but how particular interpretations of it have hardened into truth. “The problem has never been with the text, but with the context,” legal anthropologist Ziba Mir-Hosseini told the Musawah seminar.

For activists battling for reform of discriminatory laws, there’s hope—at least on paper. In 2004, Morocco redrafted its family law code to state that husbands are no longer the heads of the household and marriage is a matter of “mutual consent” between husband and wife. But even ten years on, “the results are very weak, because of the mentality here,” Lamrabet conceeded. She once addressed a group of male religious scholars about equality in the Quran. “It was like an inquisition,” she recalled wryly. “Everybody was standing up, and saying, Qiwamah [male authority] is here to demonstrate that there is no musawah [equality] in our religion!”

Not as it’s practiced in most places now. But the mood at Musawah is optimistic. At the United Nations, Musawah’s Anwar reminded the Commission on the Status of Women that Muslim women don’t need to choose between Islam and equal rights; while 4:34 is invoked by sexists, there are many more passages calling for justice, and a sound Quranic tradition saying that all humans are equal as God’s creations. In London, Anwar asked the crowd of Muslim women a fundamental question: “If we are equal before the eyes of God, why not before the eyes of men?”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com