Rachel Elizabeth Seed and Brian Seed are on the phone. They’re talking about music and whether Rachel, a photographer and filmmaker, might have been a musician had her father chosen music instead of photography as a profession. He prefers classical. She likes folk, soul and R&B. “Rachel is an American girl, is what it comes down to,” her father says. “And I am still a Brit, God help me.”

Divided as they may be on music and national allegiance (Rachel was born in England but raised in the U.S.), the Seeds have been long united by a passion for photography. And it has brought them together, more recently, on a new project by Rachel that rediscovers the work of Sheila Turner-Seed, Brian’s wife and Rachel’s mother, who died at the age of 42 in 1979.

Brian stumbled into photography at a young age, with no discernible interest to speak of other than his father’s regular reading of LIFE Magazine. When he was a teenager in London, his father saw a newspaper ad for an office boy at the TIME/LIFE office. Brian responded to the ad and became one of four “really incredibly scruffy and ill-educated urchins” running errands for a weekly wage of around 30 shillings.

When his superiors recognized that Brian was, in his own words, “maybe slightly more promising than the rest,” they promoted him to work exclusively for LIFE. There, he became steeped in photojournalism: handling equipment, assisting photographers and shipping LIFE’s daily take from London to New York. He started working closely with the legendary Cornell Capa, the younger brother of fellow LIFE photographer Robert Capa. Seed eventually left the LIFE office to become Capa’s assistant. He soon began shooting his own work, placing it in TIME, LIFE and Sports Illustrated.

Capa would play an instrumental role in Brian’s life, not only taking him under his wing as a developing photographer, but also introducing him to his future wife. When Sheila Turner, a multi-media journalist from New York, began a project interviewing photography greats, Capa helped arrange a meeting with the photojournalist Don McCullin in London. He gave her Brian’s contact information should any needs arise. Upon discovering the dismal conditions of her lodging situation, Brian helped arrange more suitable housing. The relationship blossomed from there.

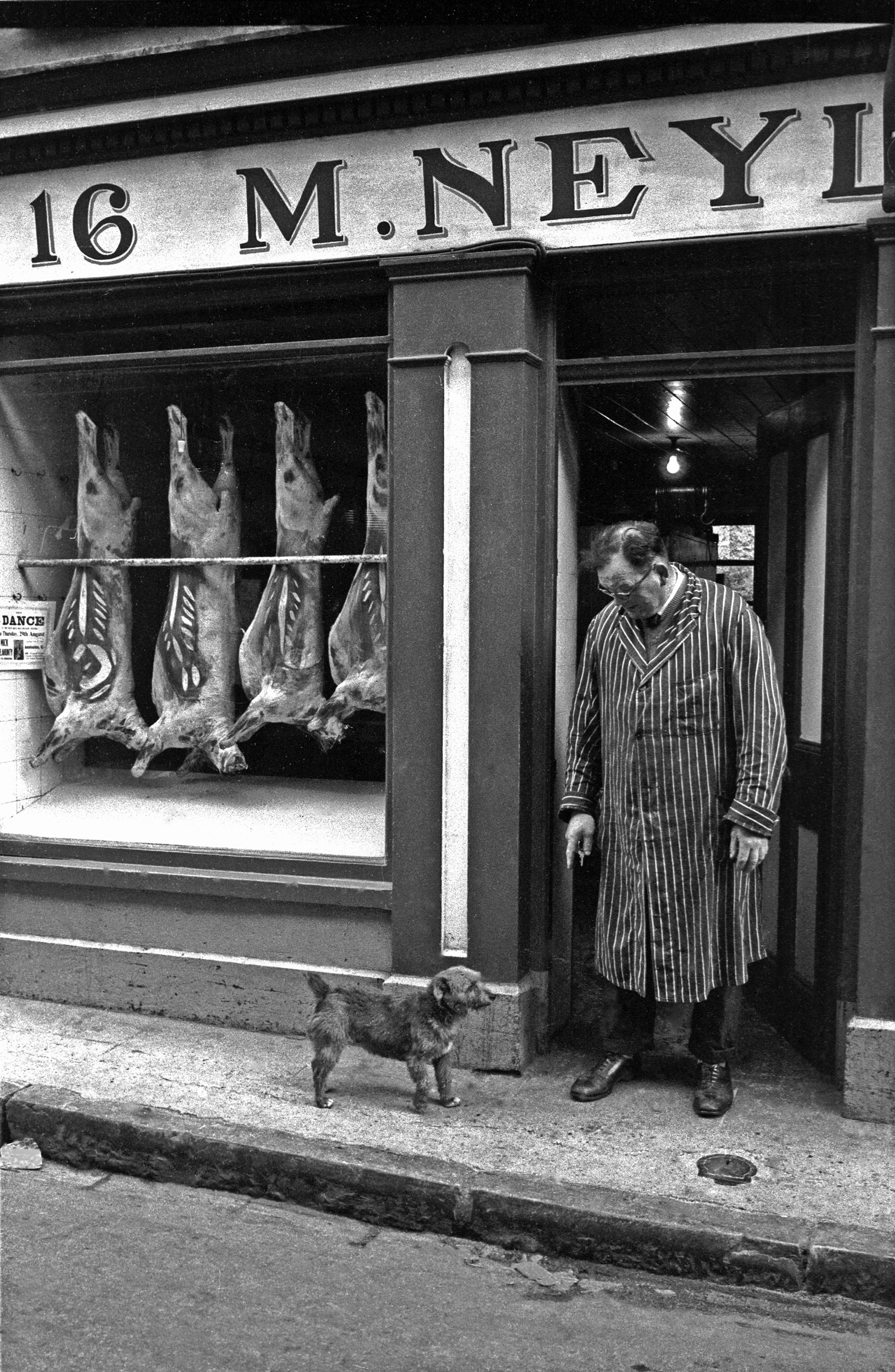

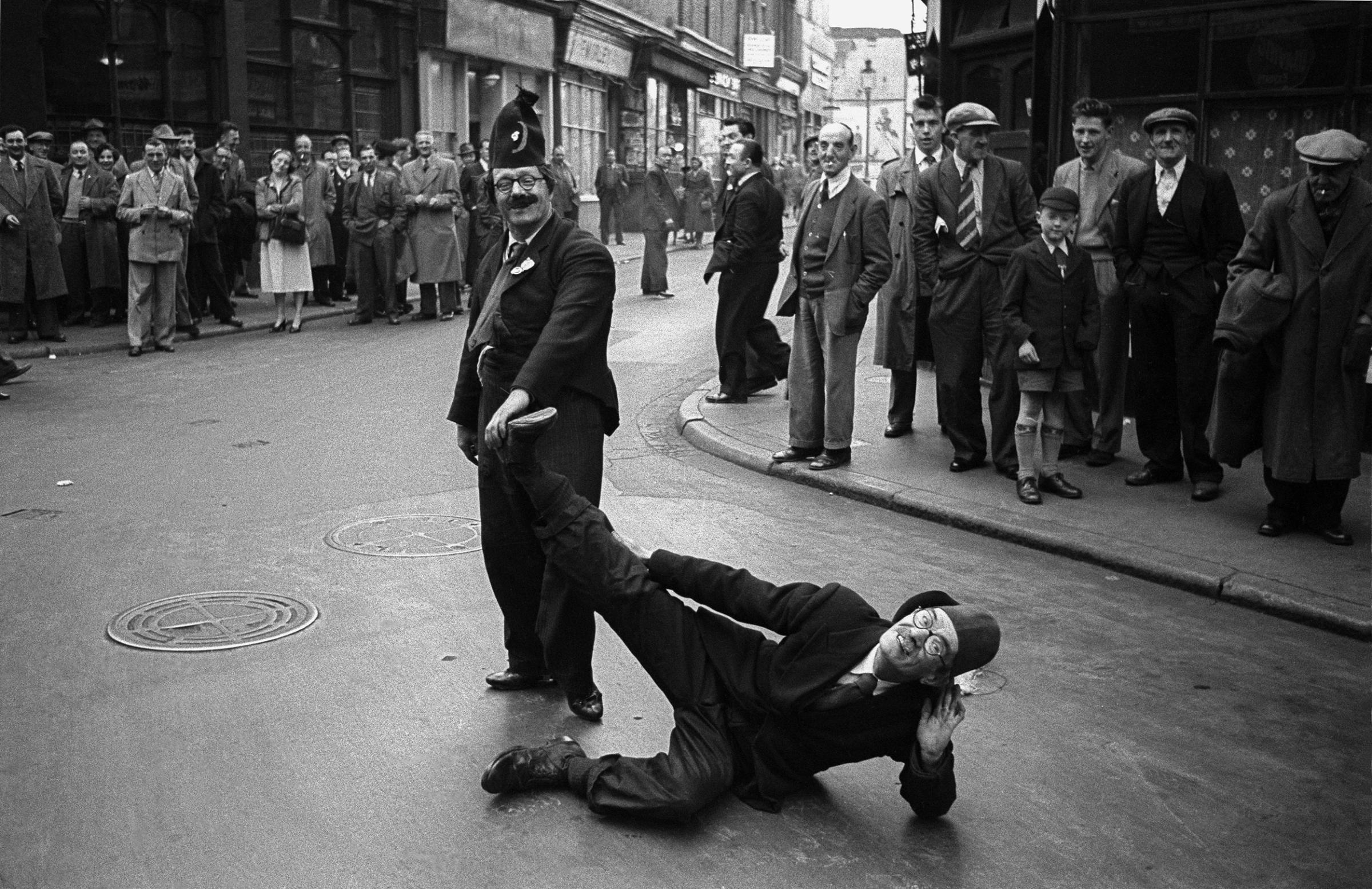

Though his work took him throughout the U.K. and beyond, it’s clear that England offered Brian’s greatest inspiration. As he says, “The British are nuts, basically. We’re a country of eccentrics.” That levity is evident throughout his work, from a photograph of a man using his bulldog as a pillow to a rugby fan caught celebrating mid-leap. He often brought this lighthearted approach to his coverage of world-famous names like Marilyn Monroe, Muhammed Ali (then Cassius Clay) and Queen Elizabeth. His eye for quirk was unmatched.

Rachel’s entry into the family business was as purposeful as her father’s was not. Between heaps of equipment and the household darkroom where Brian spent much of his time, her father’s work provided a backdrop to her childhood. When her work as a writer had her yearning to trade the solitude of her desk for more human interaction, she gravitated toward the camera.

But Rachel’s penchant for photography was not exclusively passed along by her father. The project that brought her mother to London—and, of course, to her father—stemmed from Sheila’s own love of the medium. She interviewed influential photographers like McCullin, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Lisette Model and Bruce Davidson, producing several box sets and audiovisual programs for Scholastic and Capa’s Fund for Concerned Photographers. She left in her wake boxes upon boxes of raw material, including recordings of her own voice as an interviewer, which never featured in the final edits of her work.

Then, when Rachel was just eighteen months old, Sheila died suddenly. Brian shipped her boxes to the International Center of Photography, which Capa had established five years earlier, for safekeeping. Growing up, Rachel knew that they existed. It was just a matter of feeling ready to seek them out.

It was in Capa’s office, largely untouched since his death in 2008, that Rachel heard her mother’s voice for the first time since she was a baby. Rachel then set out to interview the photographers her mother once interviewed, getting to know Sheila through them. Gradually, her excavation of her mother’s project became her own project: a documentary film called A Photographic Memory, which she is currently in the process of editing.

While the lens on the world she’d inherited from her father was more obvious, Rachel began to discover that her own sensibilities as a photographer had striking similarities to her mother’s. “It seems like there’s a kind of communication going on that’s not conscious,” she observes, “a sort of innate connection.” A year ago, she photographed the apartment building where Sheila had lived in New York City. The following day she found an old contact sheet of her mother’s with uncannily similar shots of the same building. After photographing her cousin’s daughter playing piano, she found a picture her mother had taken of her cousin at the same piano, a generation ago.

Brian, for his part, has been an integral part of the documentary, sitting for as many as 15 interviews and discussing subjects he and Rachel had never previously discussed. “When your child shows an interest in something, then you encourage them,” he says. “She started taking photographs and clearly from the beginning was taking quite good photographs. I mean, some people are born to it and some people aren’t.”

For the Seeds, photography has been more than just a shared passion and a common language. It has been, against metaphysical odds, a collaboration.

For print inquiries for Brian Seed Photography, please email Brian Seed at seed.brian@gmail.com.

For more about A Photographic Memory, please visit the website of Women Make Movies or email Rachel Elizabeth Seed at racheleseed@gmail.com.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

![Liberace [& Family] Entertainer Liberace (L) sitting with his mother (R) and looking out at his fans.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/150319-brian-seed-08.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Billy Graham [Misc.] Young members of Pentecostal sect respond to preaching of Billy Graham during his visit to London.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/150319-brian-seed-10.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Elizabeth II [RF: Misc.] Woman celebrating the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/150319-brian-seed-15.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com