Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker made headlines this week after his aide, Liz Mair, resigned on Wednesday and publicly apologized for tweeting some off-the-cuff comments about the early caucus state of Iowa.

You can agree or disagree with what Mair had to say—conservative pundit Jonah Goldberg called them “Disgusting and repulsive. Also, pretty much accurate”—but the real dust-up here has nothing to do with Mair at all.

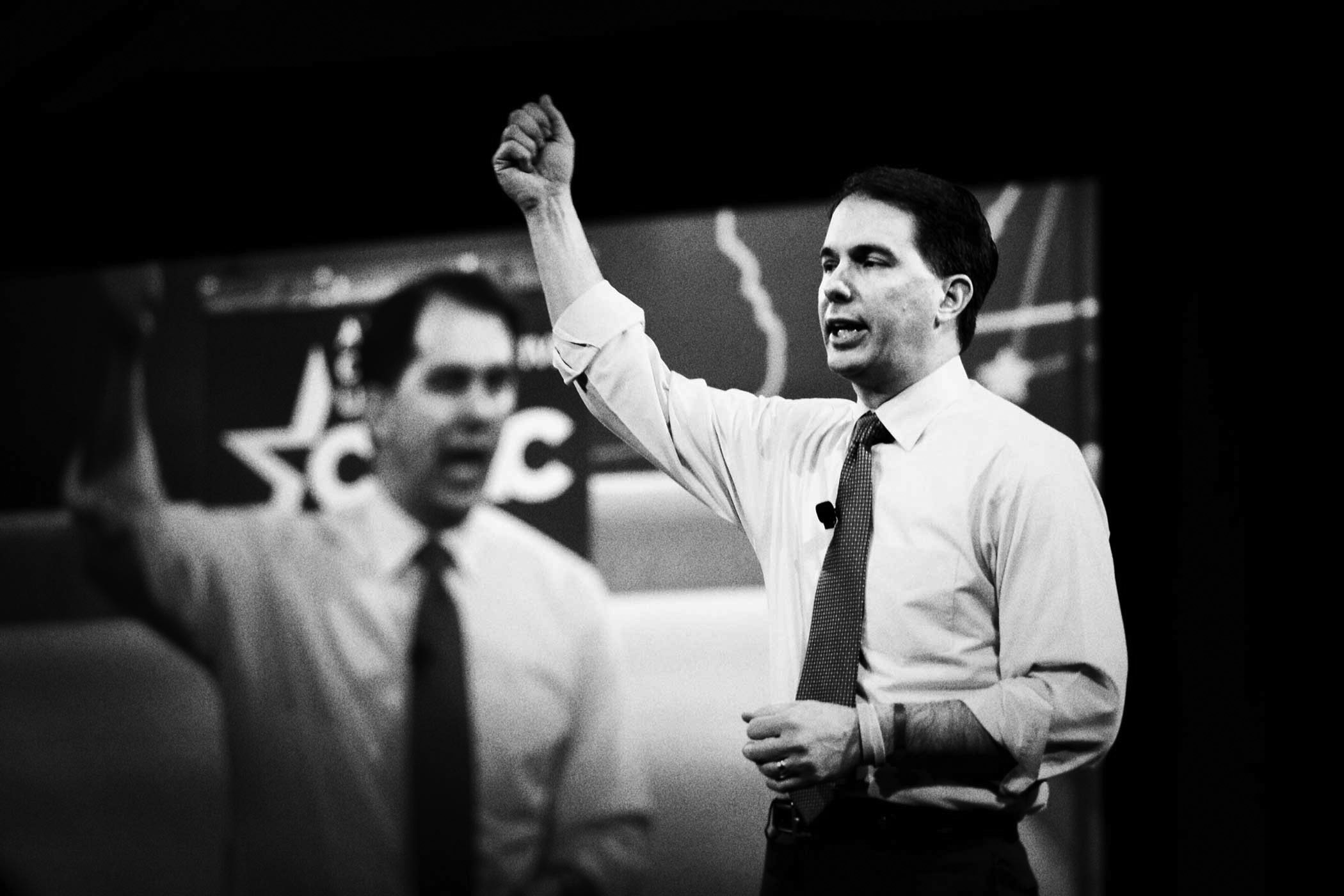

The real issue is the disconnect between who Walker says he is—“bold,” “courageous,” and “unintimidated”—and the rather meek way he handled this mini-scandal and his campaign more generally.

If Walker is indeed bold and courageous, willing to “take on the unions,” stand up to 100,000 protesters, and endure death threats “to do what’s right,” as he argues in his speeches on the early campaign trail, pundits on both sides of the aisle are asking, why didn’t he stand up for his own staffer? Why is he being intimidated by the minor vagaries of an early presidential race?

“If Walker is the guy I hope he is,” writes Goldberg, a self-described Walker booster, “He won’t just have to take on his enemies, he’ll have to take on his friends, too … Isn’t that the point of the anti-establishment movement on the right?”

Republicans and Democrats in Wisconsin explain it this way: Walker-the-governor is very, very different than Walker-the-candidate.

Walker-the-governor is bold. As governor, he has consistently pushed through far-reaching policies and then stood his ground in the face of all kinds of threats.

But Walker-the-candidate is nothing of the sort.

As a candidate, Walker has a history of being blandly genial and preternaturally vague. When he’s asked policy questions, he gives squishy, milquetoast answers, and seems willing to go to great lengths to avoid saying anything that could get him in trouble later:

Should the U.S. do more to combat ISIS? “That’s certainly something I will answer … in the future.”

Who should be Chairman of the Federal Reserve? “I’ll punt on that.”

Is President Obama a Christian? “I don’t know.”

Should the U.S. arm Ukrainian rebels? “I have an opinion on that … but I just don’t think you talk about foreign policy when you’re on foreign soil.”

What’s Walker’s position on the idea of evolution? “That’s a question politicians shouldn’t be involved in one way or another.”

Does Obama love America? “I’ve never asked him so I don’t know.”

While Walker’s supporters argue that some of those questions were unfair—and some were, admittedly, downright trolling—his colleagues in Wisconsin say that Walker has a habit of describing his policy goals as broad, ideological soundbites that sound good to moderates and conservatives, but he doesn’t tell voters what he actually plans to do.

John Torinus, a Republican commentator in Wisconsin and a former supporter of Walker, lamented recently in a column entitled, “Do Wisconsin Campaigns Mean Anything Anymore?” that Walker’s was a “government by surprise.” Torinus described Walker’s “style of governance” as “throwing out broad-brush policy shifts without a lot of input beforehand.”

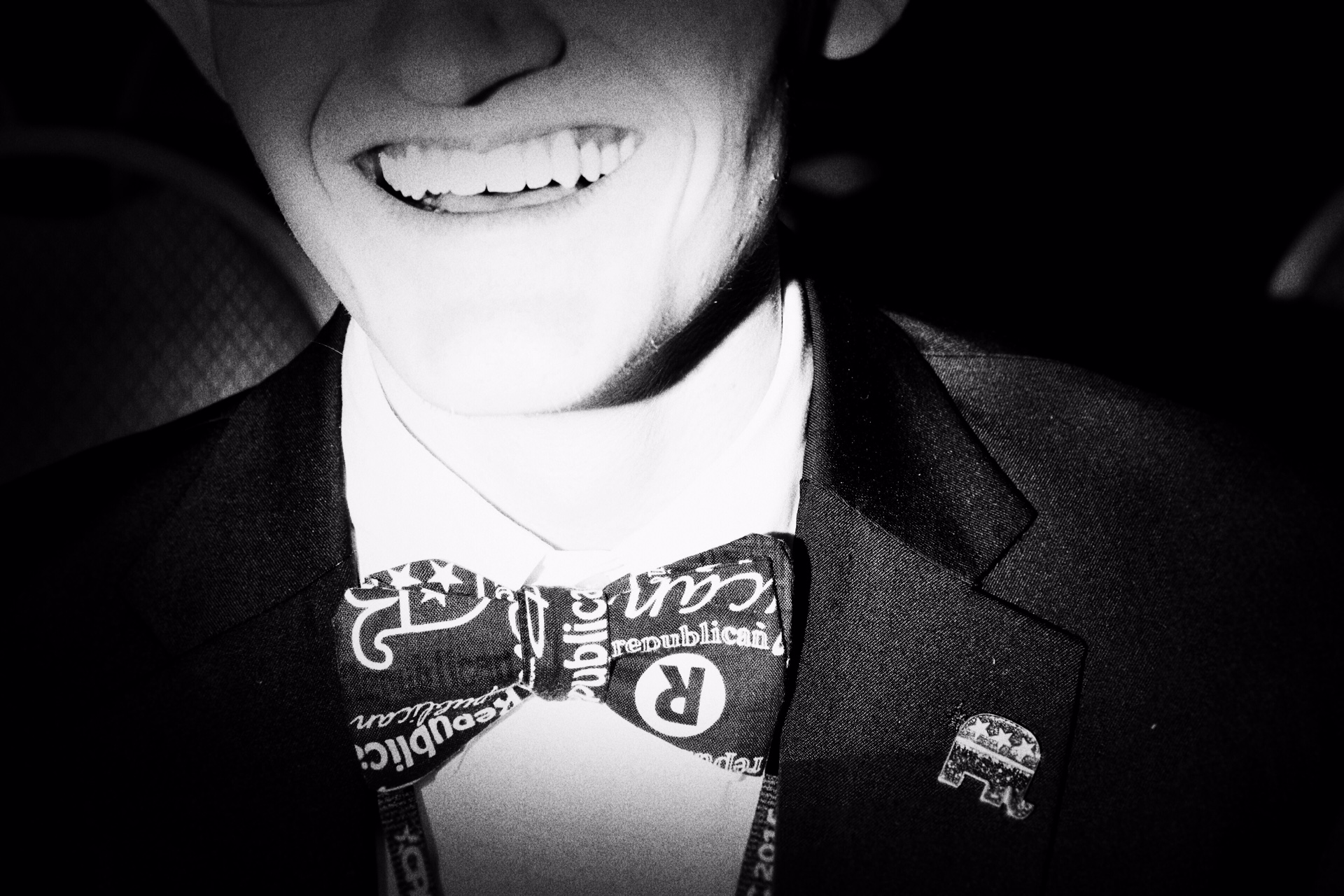

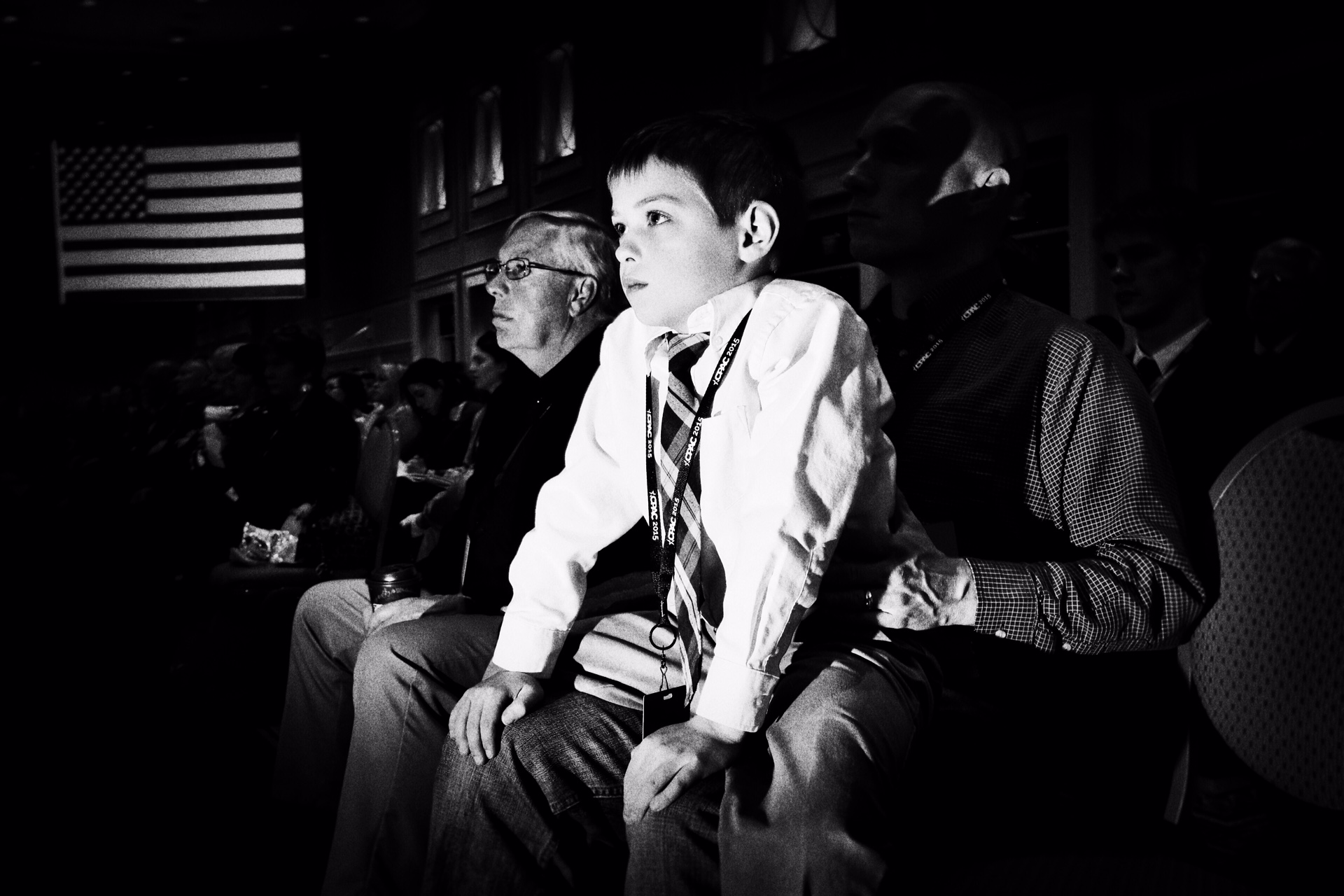

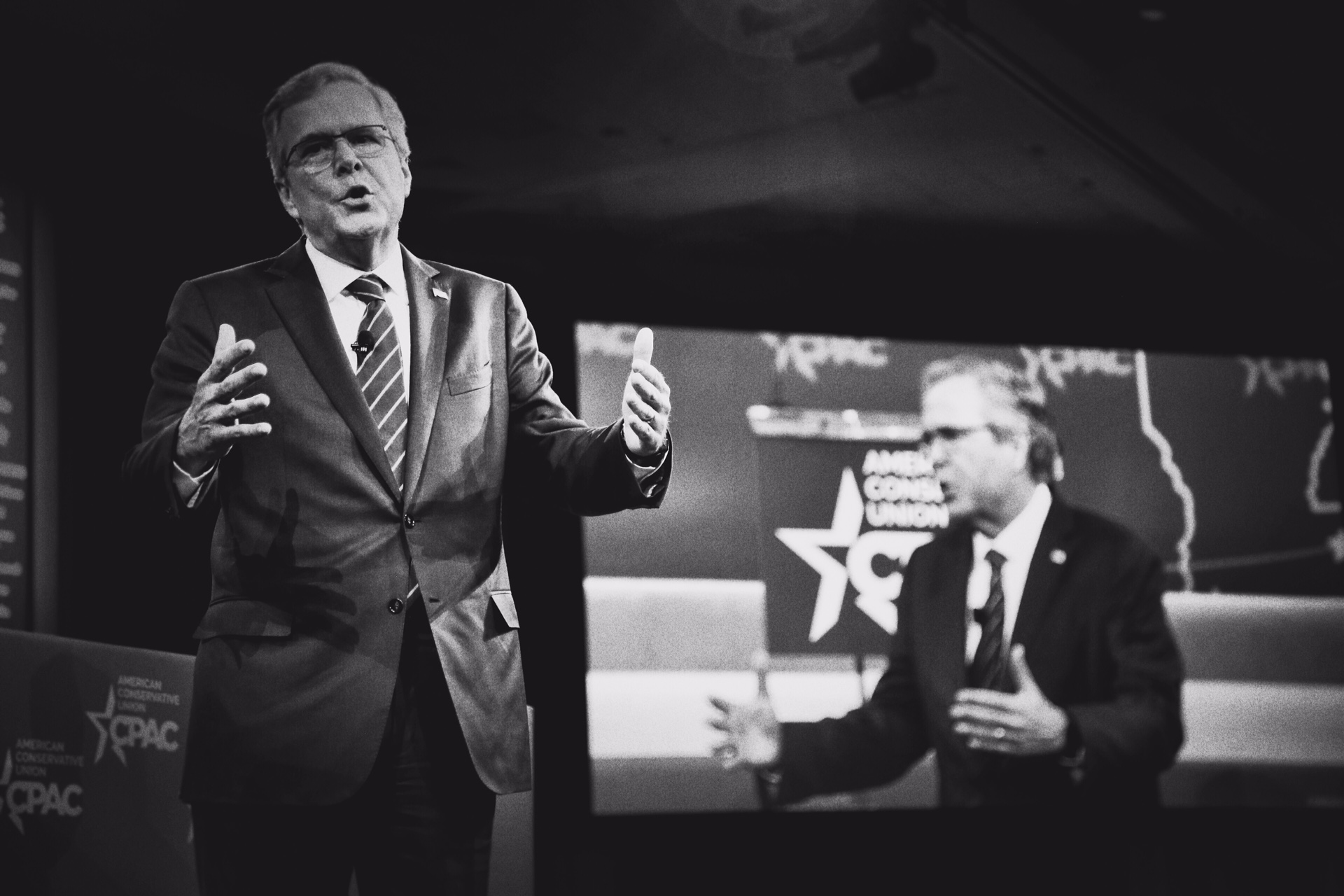

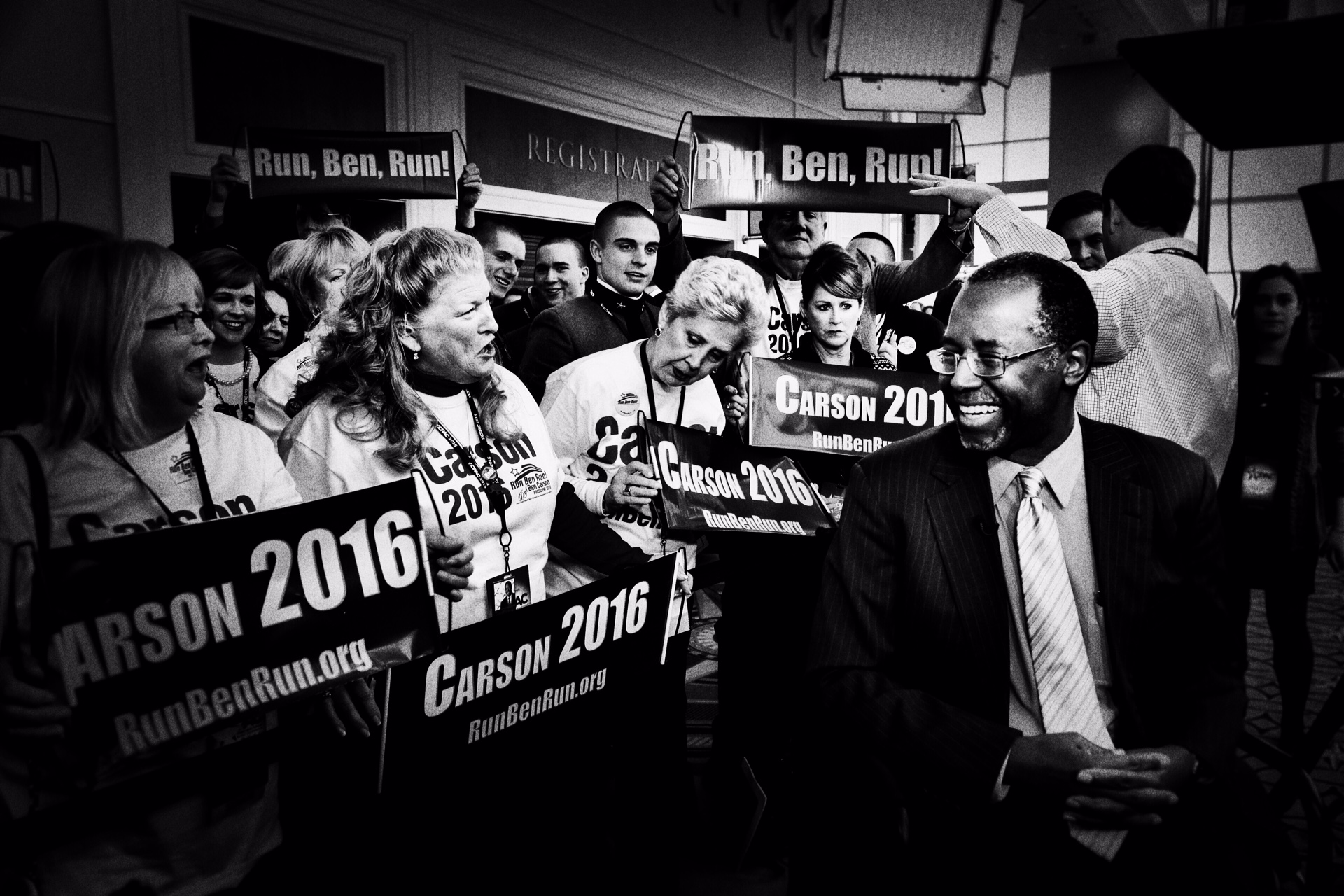

Behind the Scenes of CPAC

Jennifer Shilling, the Wisconsin senate minority leader told TIME that Walker operates in a series of “sneak attacks.” “There is this mentality that what is said doesn’t have consequences,” she said. “It’s, ‘Say whatever you need to say—we can do whatever we want once we’re in.’”

A few examples?

Right-to-work legislation. Since 2011, Walker has said on dozens of occassions that he did “not support” making Wisconsin a so-called right-to-work state. “I have no interest in pursuing right-to-work legislation in this state,” he said at the state Republican annual convention in 2012. “It’s not going to get to my desk … private sector unions have overwhelmingly come to the table to be my partner in economic development.” During the 2014 campaign, he those same lines, telling interviewers at TIME, the New York Times and in his debate with his Democratic opponent that he would “not support” right-to-work legislation.

But then, just a month into his second term, Walker announced that he would sign a right-to-work bill if the legislature passed it. On March 9, he made good on his offer. Making Wisconsin a right-to-work state “sends a powerful message across the country and across the world,” he said in celebration.

Abortion. Last October, when he was running for reelection–and the polls were tight in his famously blue state—Walker cut an ad in which he stared directly into the camera and promised to support a law that would leave “the final decision” about abortion “to a woman and her doctor.”

But then, four months later, Walker announced that he would sign a law banning abortions of any kind after 20 weeks.

Limiting collective bargaining. Walker’s signature law, Act 10, which passed in early 2011 and gutted collective bargaining for almost all public sector unions, catalyzed a massive, nationwide reaction on the left. At some point, 100,000 protesters convened on the Wisconsin statehouse for months on end. One reason for the outrage? No one—including Wisconsin state legislators—had any idea whatsoever that Walker had Act 10 up his sleeve. During his 2010 campaign, He never said he planned to go after collective bargaining. He never so much as hinted at it—not in his campaign material, not in his stump speeches, and not during the debates or in conservations with top allies in the state legislature.

But then, less than a month into his term, in February 2011, he, in his words, “dropped the bomb.”

Walker’s political campaign staff point out that he never lied. Walker never said he wouldn’t sign right-to-work, and he has always been a pro-life, fiscal conservative.

More Must-Reads from TIME

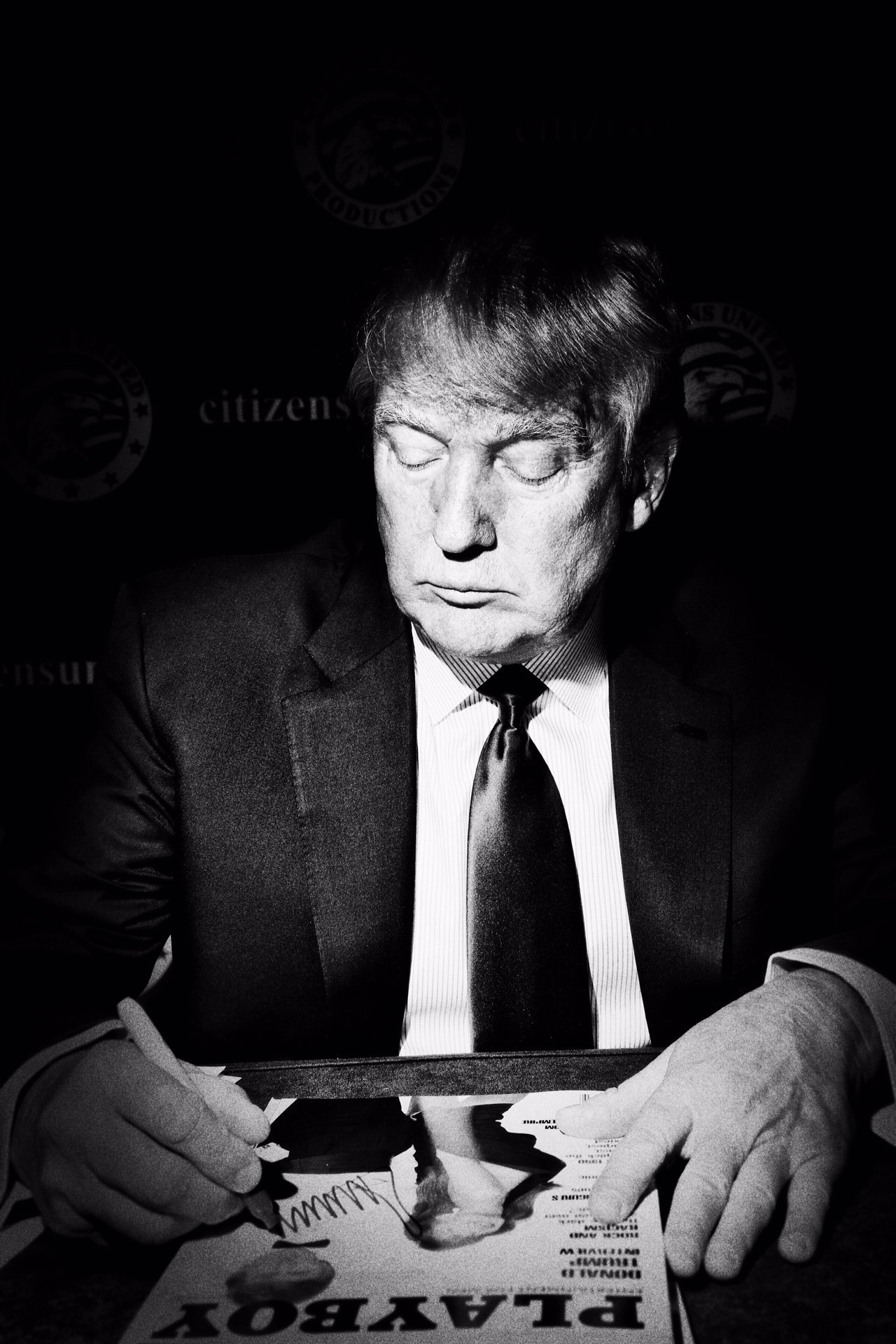

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Haley Sweetland Edwards at haley.edwards@time.com