“Shy,” “self-effacing” and “introspective.” The words LIFE used to describe Cesar Chavez in 1966 may not sound like the qualities befitting one of America’s most effective labor leaders. But Chavez’s power, at least as LIFE observed in that year, was not to be found in displays of volume or might. It was his quiet leadership and deep commitment to nonviolence that empowered thousands of farm workers to transform their working conditions into something more humane.

This legacy has, in recent years, been both recognized and complicated. Last year, President Obama declared Chavez’s birthday, March 31, a national holiday. Also in 2014, author Miriam Pawel published The Crusades of Cesar Chavez, the first comprehensive biography of Chavez, offering a more nuanced view of his leadership. For decades, Chavez had been held up more as hero than human, and Pawel’s thorough excavation of his life injects humanity—blemishes and all—into the narrative.

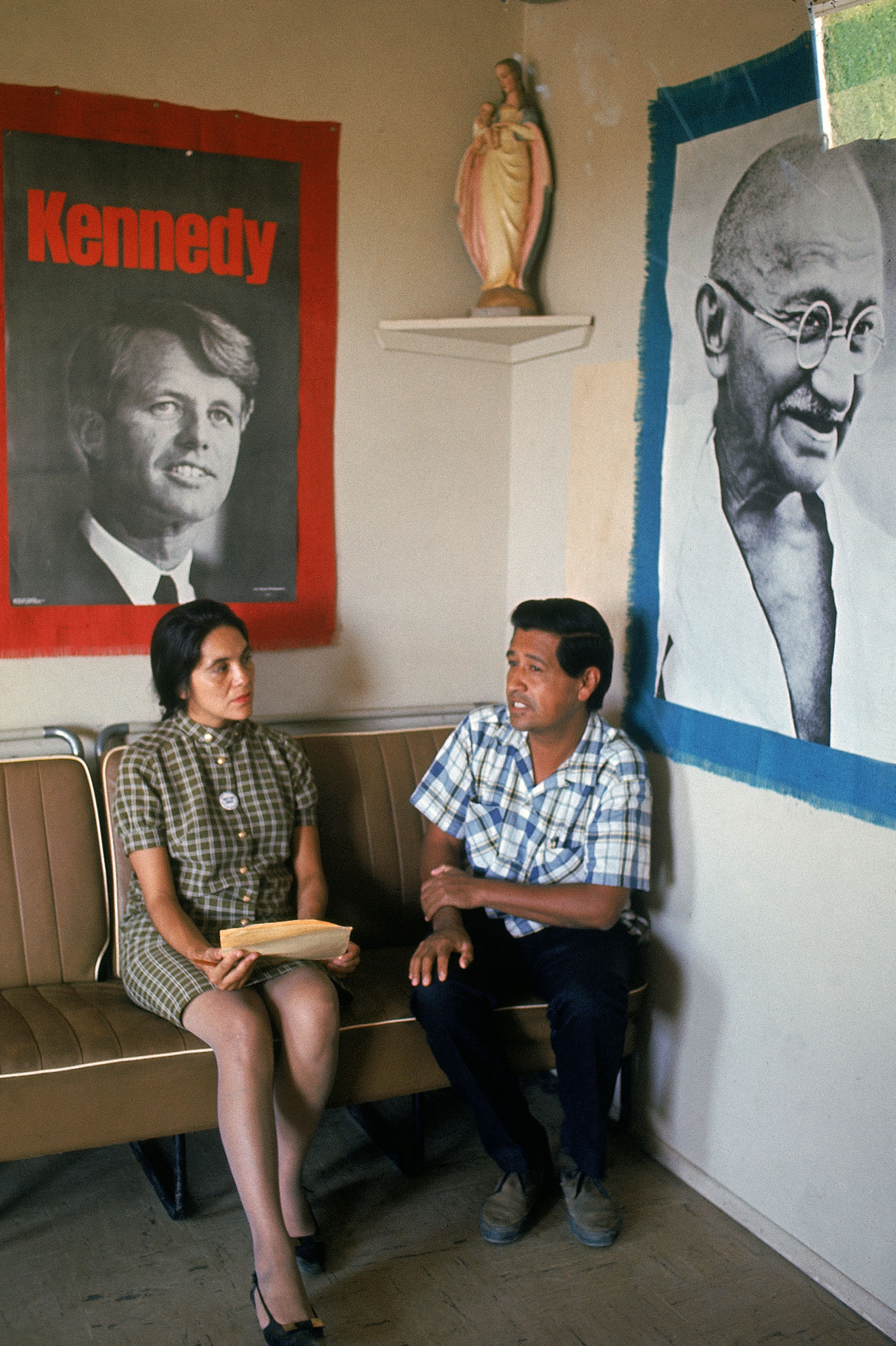

But when LIFE covered him during the mid-1960s, the prevailing image of Chavez was that of the quiet leader. Chavez, LIFE wrote, did not seek out the spotlight. During a 25-day, 250-mi. march to Sacramento, he “marched in the third row, largely unnoticed.” Neither did he dictate orders. When giving driving directions, one follower observed, “He doesn’t say, ‘Turn here, go there.’ He says, ‘Now we turn here. Now let’s stop there.’”

The son of a migrant farmworker, Chavez was exposed to the plight of laborers from a young age. He left school after seventh grade to work in the fields himself, so his mother would not have to. Addressing the kinds of conditions under which his family lived and worked would become his own life’s work, as he would go on to co-found the National Farm Workers Association with fellow labor leader Dolores Huerta.

In 1965, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee—with which the NFWA would soon merge to form the United Farm Workers of America—launched what would be a five-year strike against grape growers in California. When LIFE dispatched Arthur Schatz to cover the strike in 1968, Schatz’s lens found the introspective leader the magazine had profiled two years earlier. Standing in solidarity with workers, he physically embodied his own philosophy on the work he did: “In organizing people, you have to get across to them their human worth and the power they have in numbers.”

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com