Gurdeep Pall was confident Skype’s automatic translation program would work. But as Microsoft’s corporate vice president in charge of Skype prepared to hold the first public demonstration of the program last May, Pall found himself worrying about the room itself. “Any sound that goes into the microphone, you basically have logic running trying to figure out what the sound said,” he says. “You can have feedback or you can have somebody coughing faraway that the mic picked up, somebody shifting far away, the squeak from their foot.”

Pall’s anxiety was for naught. An audience of several hundred reporters and industry insiders watched on as Pall and a native German speaker held a nearly flawless conversation through the company’s prototype of Skype Translator. Roughly a second after Pall Spoke, subtitles in German and English appeared at the bottom of the screen, and a synthetic Siri-like voice read the words aloud to the German caller. The audience murmured in astonishment, but the program didn’t falter as it shot back a translation from German to English. Pall, on the other hand, was flustered as his jitters about the room metastasized to two presenters who were whispering to one another nearby throughout the demonstration. “I’m thinking, ‘Get out of here!’” Pall recalls, laughing.

Researchers working on automatic translation technology like this are familiar with this blend of hope and anxiety. The concept of a universal translator has long been a fixture of science fiction, not to mention a dream of inventors and linguists since long before computers existed. The granodiorite slab announcing the kingly reign of Ptolemy V in Egypt circa 196 BC, better known as the Rosetta Stone, might be considered an early stab at the idea. In the 1930s, two inventors filed patents for “mechanical dictionaries” promising to translate words in real time. And in more recent decades, firms ranging from NEC to Jibbigo have periodically tried to crack the problem. But as practical reality, the idea has been perennially delayed.

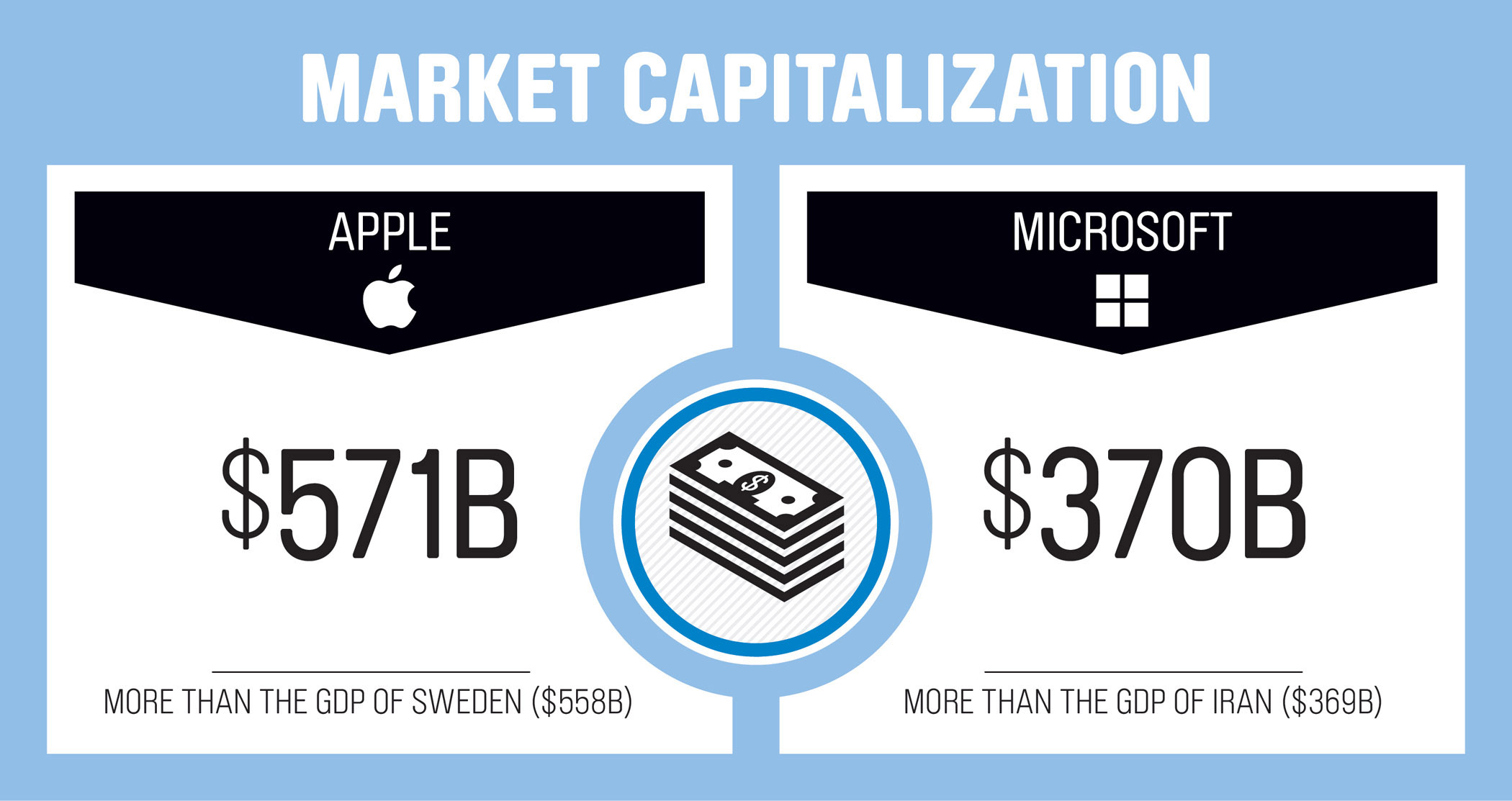

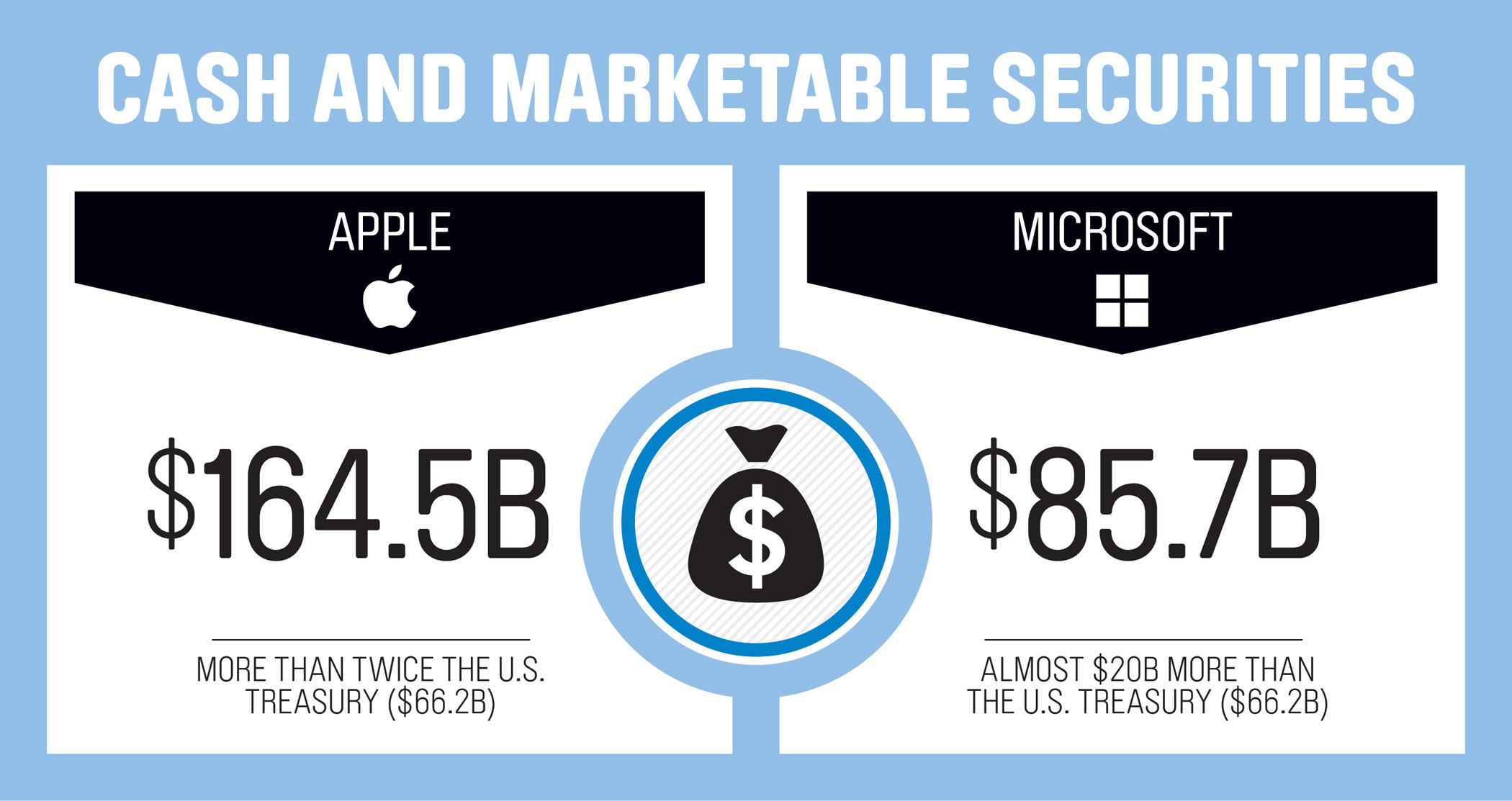

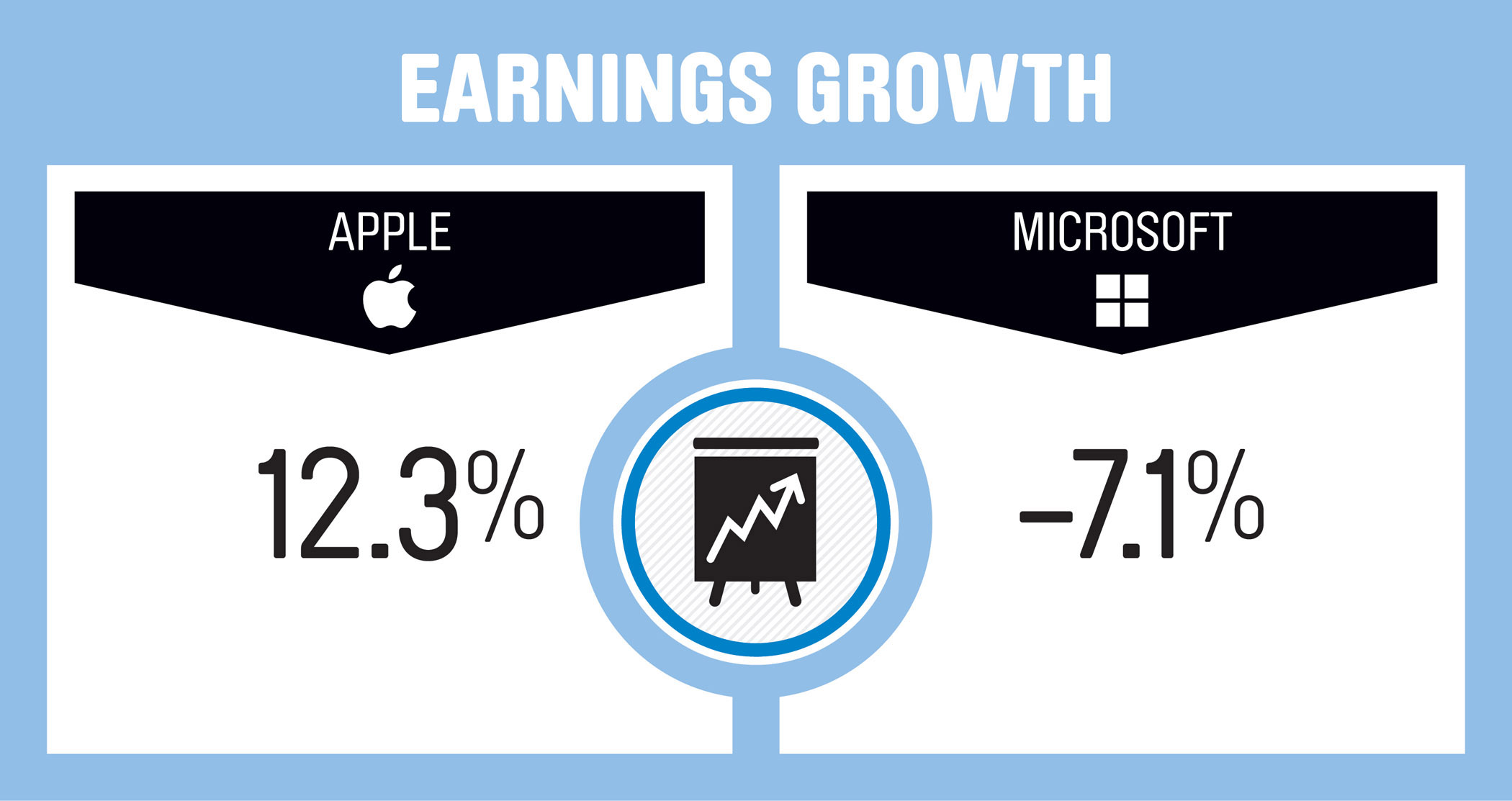

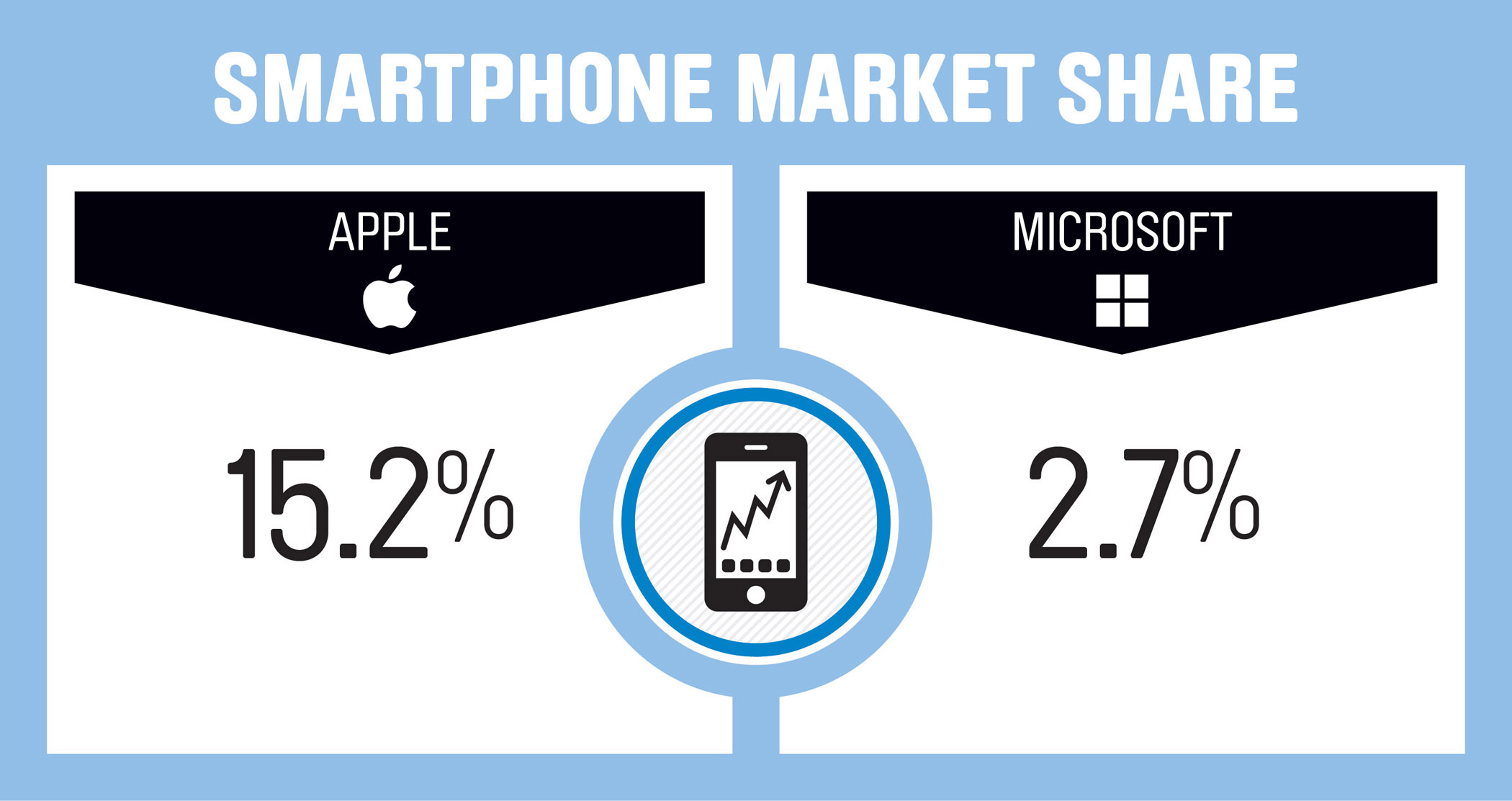

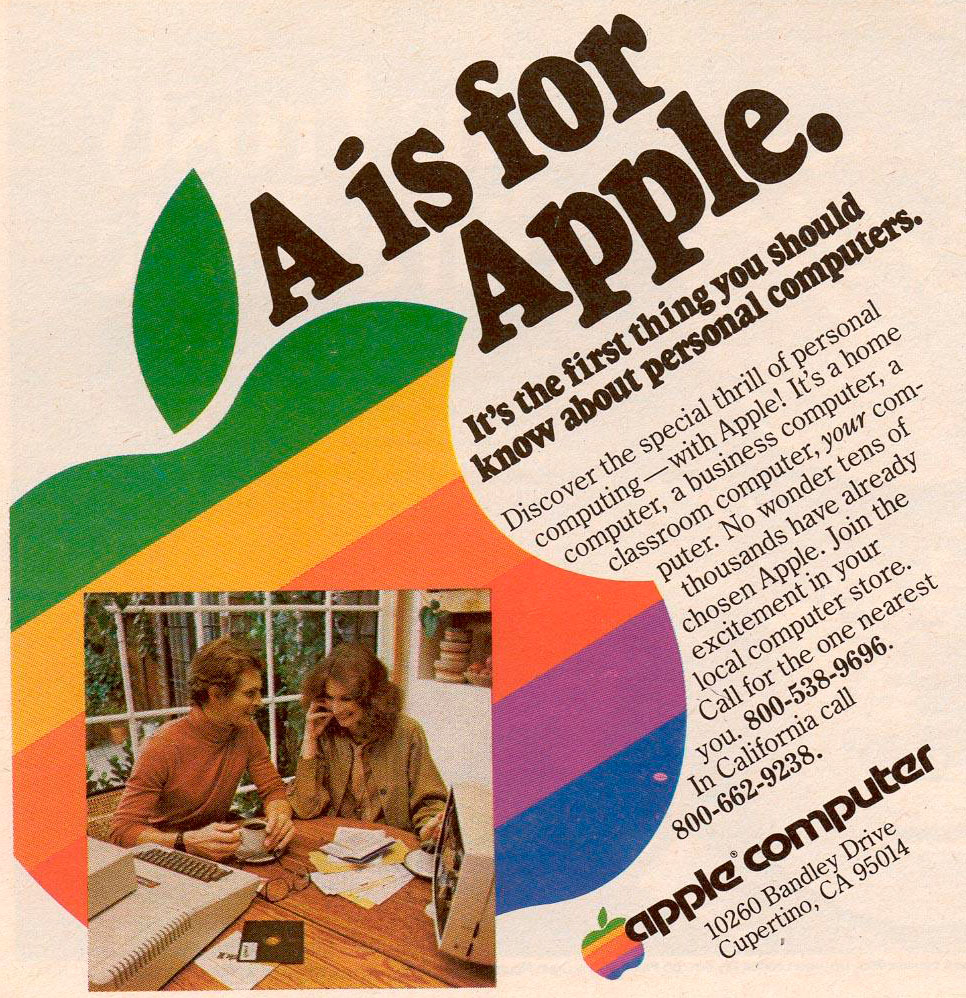

Apple vs. Microsoft in 11 Slides

Now, advances in so-called machine learning—computer programs that can essentially self-teach with enough exposure to spoken language—hope for a universal translator is increasingly replacing anxiety. What has changed from previous generations is that the underlying technology thrives through use, trial and error, recorded and reviewed, ad nasueam. The current crop of translation software gets smarter, researchers and programmers say, the more it absorbs. “The more data you have, the better you’re going to do,” explains Lane Schwartz, a linguistics professor at the University of Illinois.

Which is why Microsoft released a preview version of Skype Translator to a limited number of users last December. (The Redmond, Washington-based tech giant bought Skype for $8.5 billion in 2011.) The program is expected to reach a major milestone near the end of March. Late last year, Google announced its translation app for text would include a “conversation mode” for the spoken word. Baidu, the so-called Google of China, has had a similar feature available in its home market for several years. And the forthcoming release of the Apple Watch, a powerful computer with echoes of Dick Tracey’s famous wrist wear, has some speculating that near-instant translation might be the nascent wearables market’s killer app.

That leaves a handful of search giants—Microsoft, Google and Baidu—racing to fine-tune the technology. Andrew Ng, Baidu’s chief scientist likens what’s coming next to the space race. “It doesn’t work if you have a giant engine and only a little fuel,” he says. “It doesn’t work if you have a lot of fuel and a small engine.” The few companies that can combine the two, however, may blast ahead.

So Many Fails

There’s no shortage of false summits in the history of translation. Cold War footage from 1954 captured one of the earliest machine translators in action. One of the lead researchers predicted that legions of these machines might be used to monitor the entirety of Soviet communications “within perhaps 5 years.” The demonstration helped generate a surge of government funding, totalling $3 million in 1958, or $24 million in present-day dollars.

But by the 1960s, the bubble had burst. The government convened a panel of scientific experts to survey the quality of machine translations. They returned with an unsparing critique. Early translations were “deceptively encouraging,” the Automatic Language Processing Advisory Committee wrote in a 1966 report. Automatic translation, the panel concluded, “serves no useful purpose without postediting, and that with postediting the overall process is slow and probably uneconomical.”

Funding for machine translation was drastically curtailed in the wake of the report. It would be the first of several boom and bust cycles to buffet the research community. To this day, researchers are loath to predict how far they can advance the field. “There is no magic,” says Chris Wendt, who has been working on machine translation at Microsoft Research for nearly a decade. But he admits that the latest improvements resulting from artificial intelligence can, at times, be mystifying. “There are things that you don’t have an explanation for why it works,” he says.

Wendt works out of Building 99, Microsoft’s research hub on the western edge of its Redmond campus. The building’s central atrium is wrapped by four floors of glass-walled conference rooms, where Microsoft engineers and researchers can be seen working on pretty much any project they please. The open-ended aspect of their work is a point of pride enshrined in the lab’s mission statement. “It states, first and foremost, that our goal as an institution is to move the state of the art forward,” said Rick Rashid in 2011, twenty years after he launched the lab, according to a Microsoft blog post celebrating the milestone. “It doesn’t matter what part of the state of the art we’re moving forward, and it doesn’t say anything in that first part of the mission statement about Microsoft.”

In other words, if Microsoft’s researchers want to tinker with strange and unproven technologies, say motion-sensing cameras or holographic projectors, nobody is likely to stop them. In the mid-2000’s, there were few technologies quite as strange and unproven as “deep neural networks,” algorithms that can parse through millions of spoken words and spot the underlying sound patterns. Say, “pig,” for instance, and the algorithm will identify the unique sound curve of the letter “p.” Expose it to more “p” words and the shape of that curve becomes more refined. Before long, the algorithm can detect a “p” sound across multiple languages, and exposure to those languages further attunes its senses. “P” words in German (prozent) improves its detection of “p” words in English (percent).

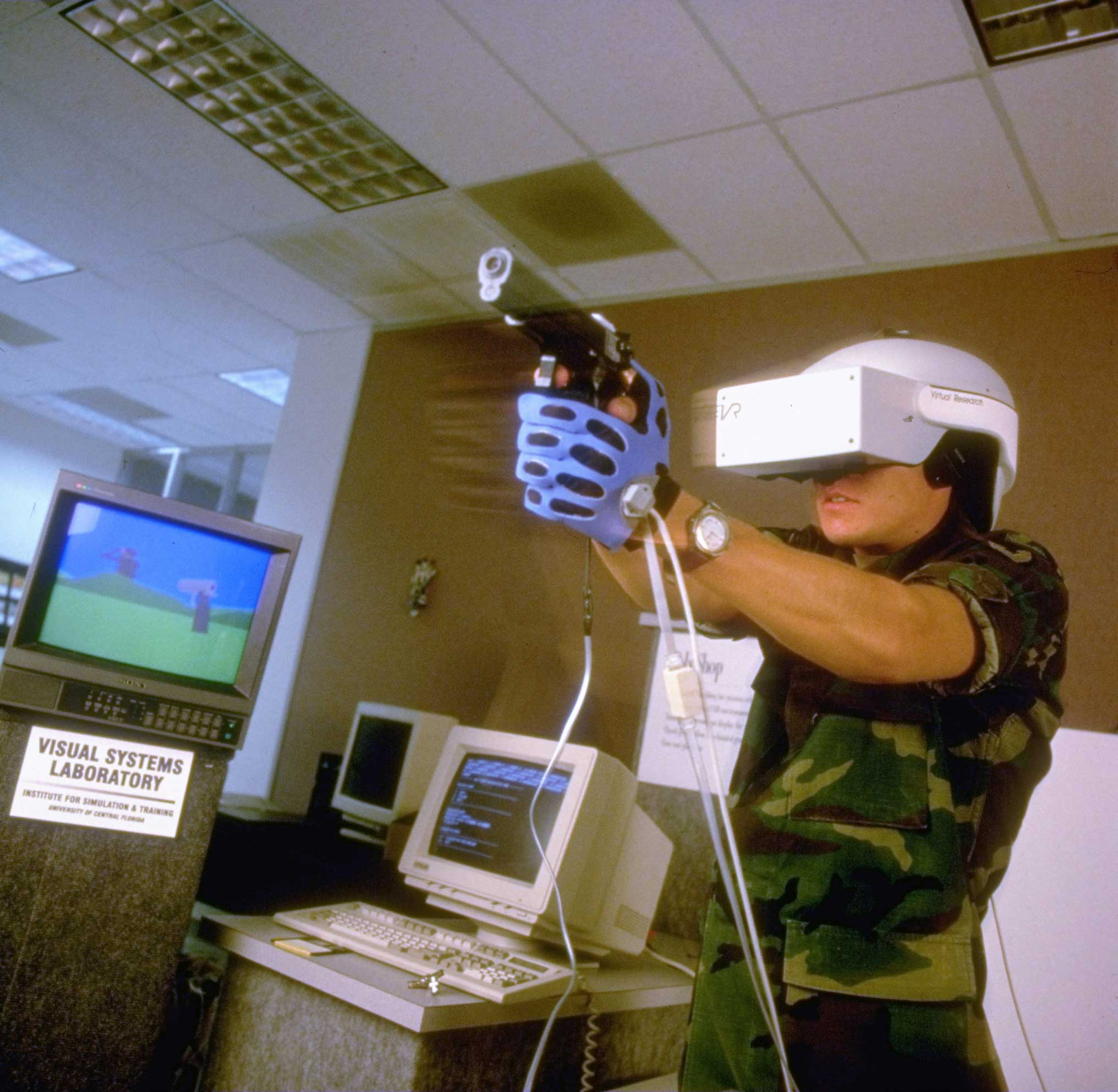

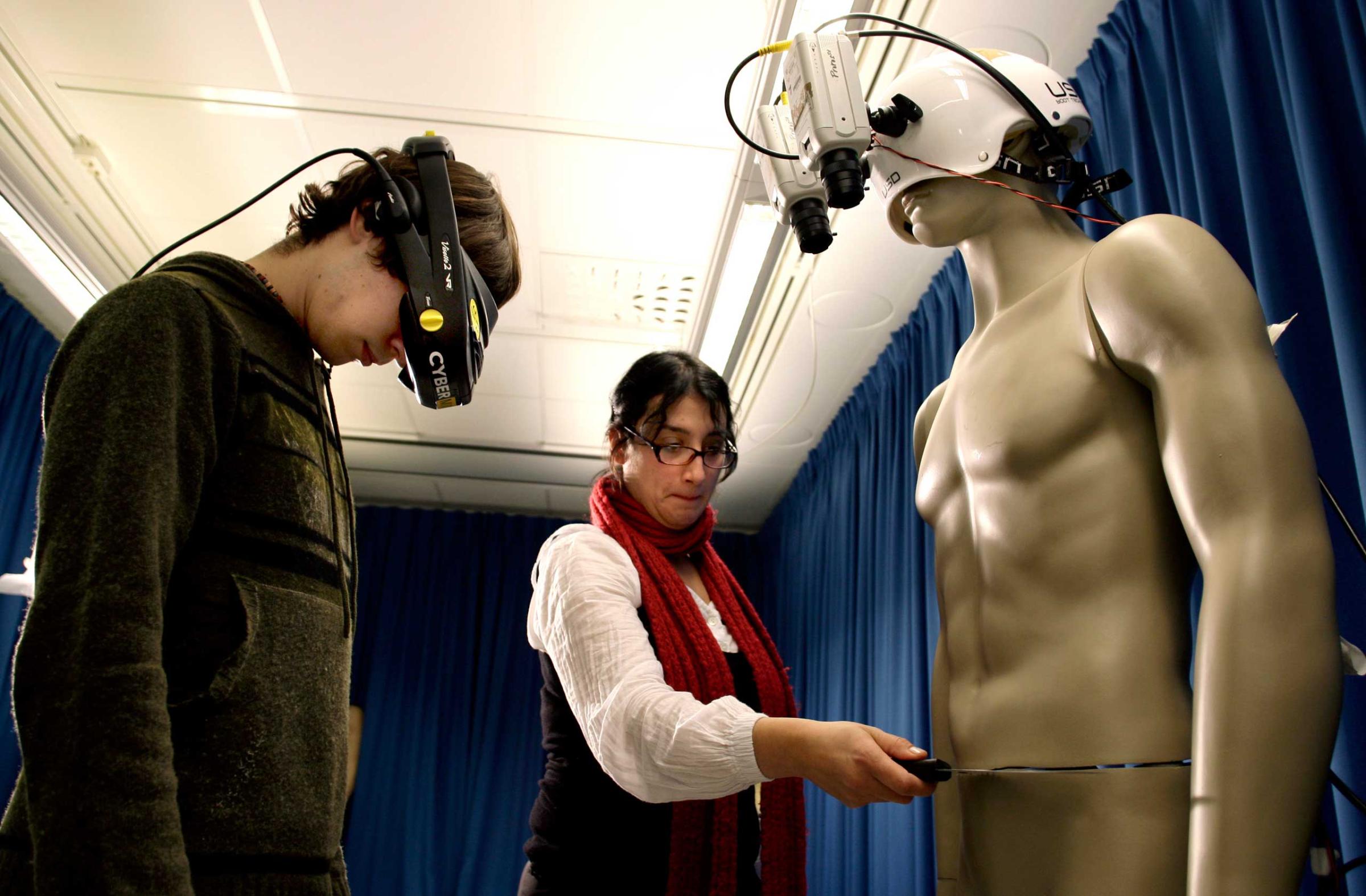

See The Incredibly Goofy Evolution of Virtual Reality Headsets

Those same lessons, it turns out, apply to volume, pitch or accents. A lilt at the end of the sentence may indicate that the speaker has asked a question. It may also indicate that the speaker talks like a Valley girl. Expose the deep learning algorithm to a range of voices, however, and it may begin to notice the difference. This profusion of voices, which used to overwhelm supercomputers, now improves their performance. “Add training data that is not perfect, like people speaking in a French accent, and it does not degrade overall quality for people speaking without a French accent,” says Wendt.

The results of deep neural network research in language applications stunned Microsoft’s research team in 2011. Error rates in transcription, for instance, plummeted by 50%—from one out of every four words to one out of eight. Until then, the misunderstood word was one of the most persistent and insurmountable obstacles to machine translation. “The system cannot recover from that because it takes that word at face value and translates it,” explains Wendt. “Employing deep learning on the speech recognition part brought the error rate low enough to attempt translation.”

Speaking into Skype Translator, the commercial face of all of Microsoft’s linguistic research, shows how far things have come. The sound of your voice zips into Microsoft’s cloud of servers, where it is parsed by a panoply of software developed by the company. The team that developed those green squiggly lines under grammatical errors in Word documents laid the groundwork for automatic punctuation, for example. The team that created Microsoft’s translation app, which is currently used to translate posts on Facebook and Yelp, provided the engine for text translation. The team that developed the voice for Cortana, Microsoft’s voice-activated personal assistant similar to Apple’s Siri, helped develop the voice for Skype.

When Microsoft’s researchers debuted a prototype of Skype Translator at the company’s version of an annual science fair, they enclosed it in a cardboard telephone booth, modeled after the time-traveling machine from the Dr. Who television series. Co-founder Bill Gates stepped inside and phoned a Spanish speaker in Argentina. The speaker had been warned that when the caller said, “Hi, it’s Bill Gates,” it wasn’t a joke. It really would be Bill Gates. What did Gates say? Pretty much what everyone says at first, according to the team: “Hi. How are you? Where are you?”

My Turn

I posed the same questions to Karin, a professional translator hired for a hands-on demonstration at Microsoft’s Building 99. She answered in Spanish, and paused as Skype’s digital interpreter read a translated reply: “Hello, nice to meet you. Now I’m in Slovakia.”

The program has the basic niceties of conversation down cold, and for a moment, the Star Trek fantasy of a “universal translator” seemed tantalizingly within reach. But then a few hiccups emerged as the conversation progressed. Her reason for visiting New York was intelligible, but awkwardly phrased: “I want to meet all of New York City and I want to attach it with a concert of a group I like,” from which I gathered that she wanted to see a concert during her visit. I asked her if the program often faltered in her experience. “In the beginning,” came the translated reply, “but each time it gets better. It’s like one child first. There were things not translated, but now he’s a teenager and knows a lot of words.”

With some 40,000 people signed up to use Skype Translator, it has been getting a crash course in the art of conversation, and those words could work wonders on its error rates. An odd quirk of machine translation systems is that they tend to excel at translating European Union parliamentary proceedings. For a long time the EU produced some of the best training data out there: a raft of speeches professionally translated into dozens of languages.

But Microsoft is rapidly accumulating its own record of casual conversations. Users of the preview version are informed that their utterances may be recorded and stored in an anonymous, shuffled pile that makes it impossible to trace the words back to their source, Microsoft stresses. The team expects the error rate to drop continuously as Skype Translator absorbs slang, proper names and idioms into its system. Few companies can tap such a massive corpus of spoken words. “Microsoft is in a good position,” says Wendt. “Google is also in a good position. Then there’s a big gap between us and everyone else.”

For now, the Skype team is focused on adding users and driving down error rates, with the long-run goal of releasing instant translation as a standard feature for Skype’s 300 milllion users. “Translation is something we believe ought to be available to everybody for free,” says Pall.

That raises an awkward question for professional translators like Karin. “Do you feel threatened by Skype Translator,” I asked her through the program. “Not yet,” was her translated reply, read aloud by her fast-developing, free digital rival.

Read next: Here’s Why Microsoft Is Giving Pirates the Next Windows for Free

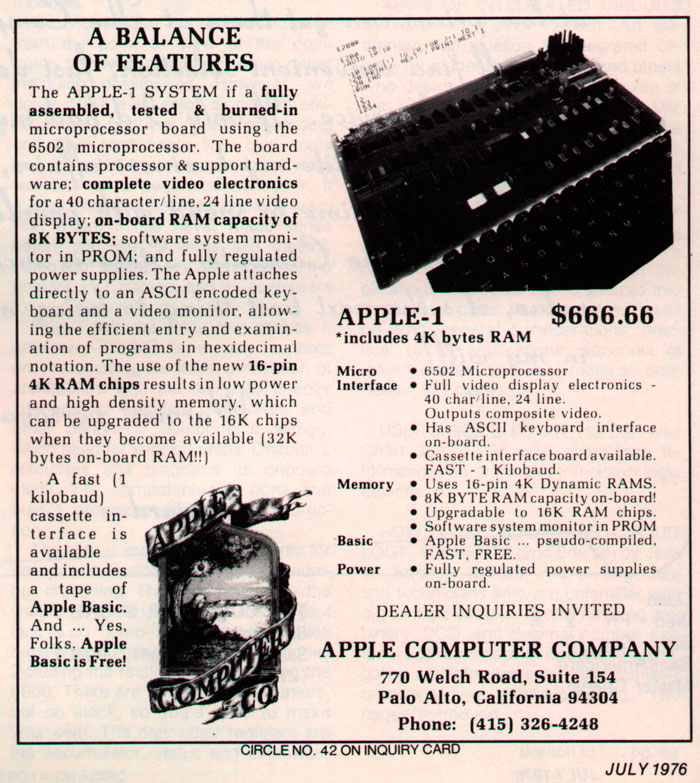

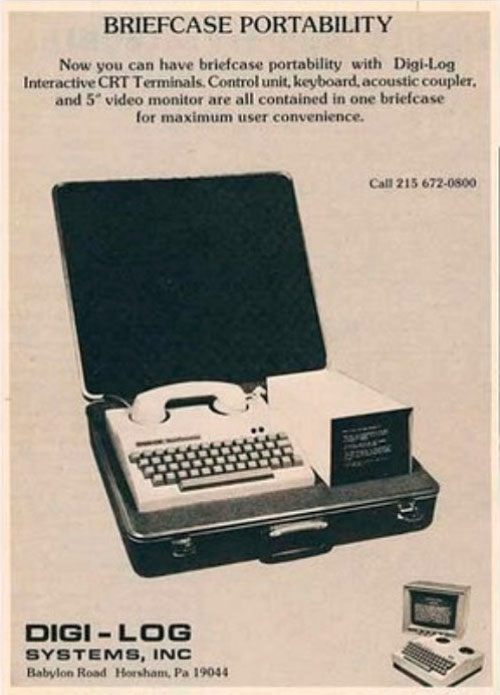

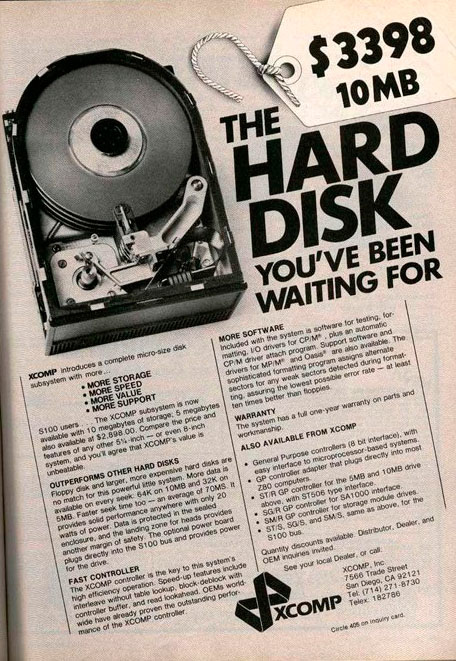

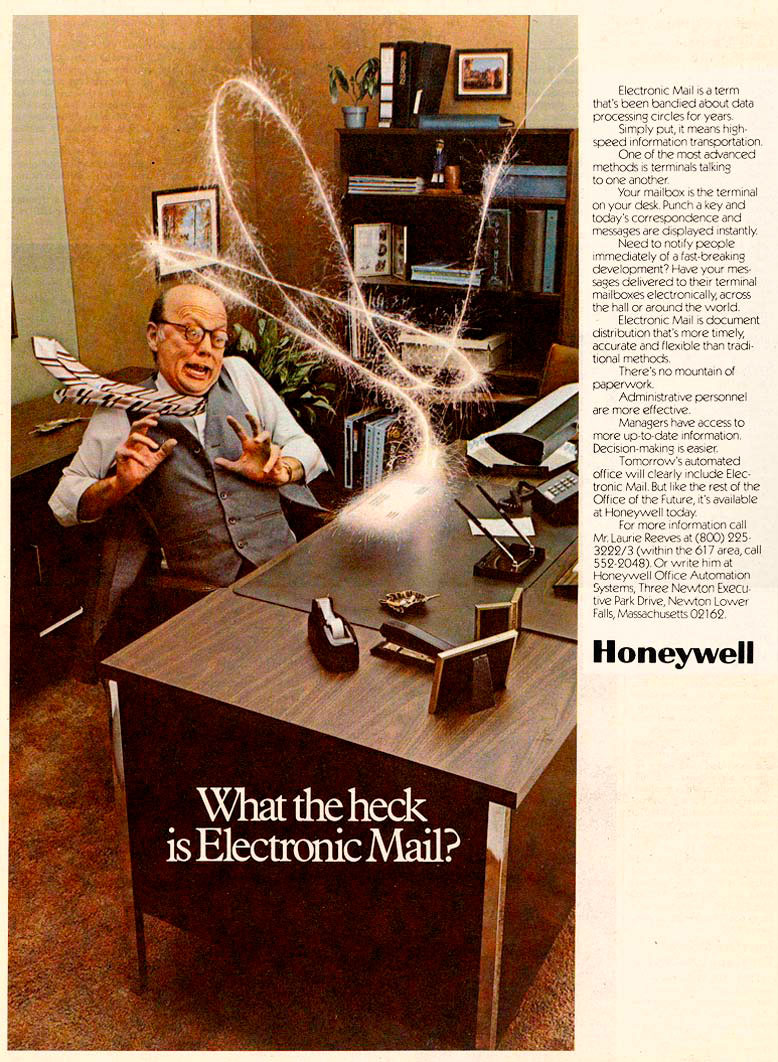

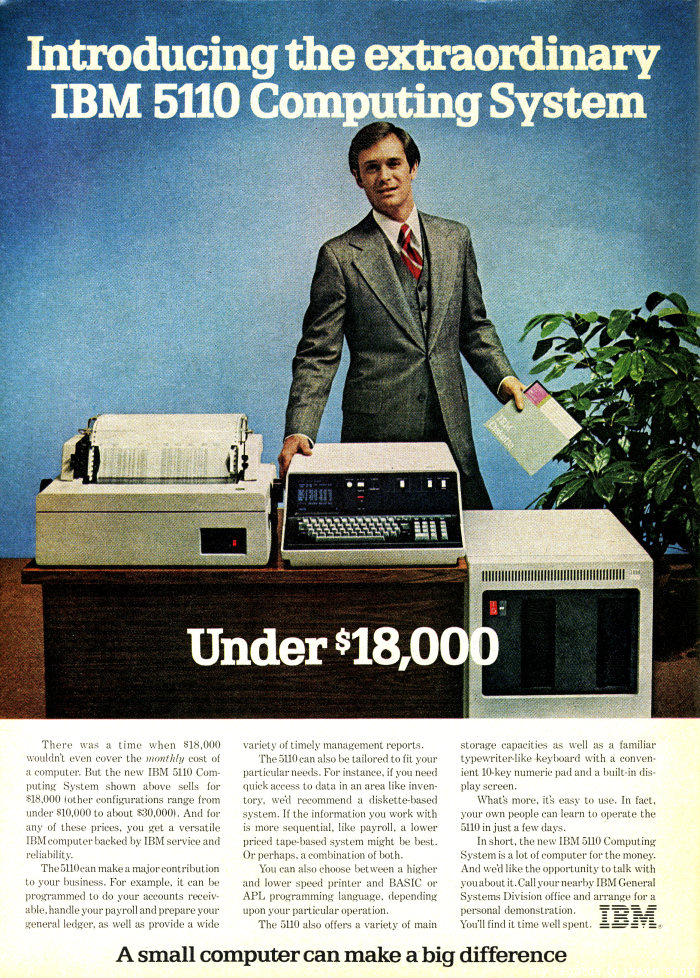

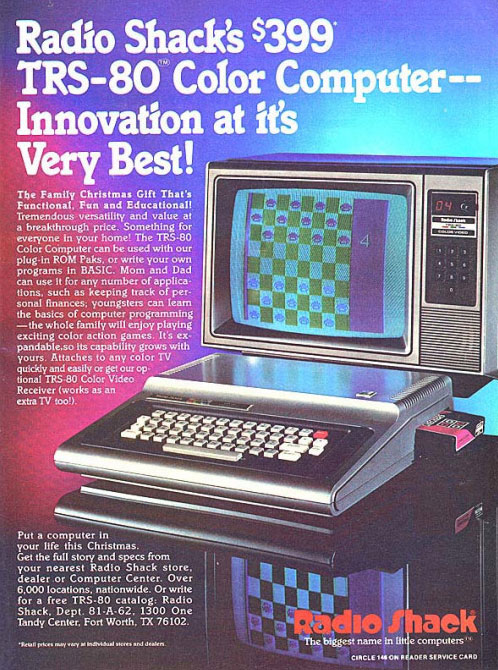

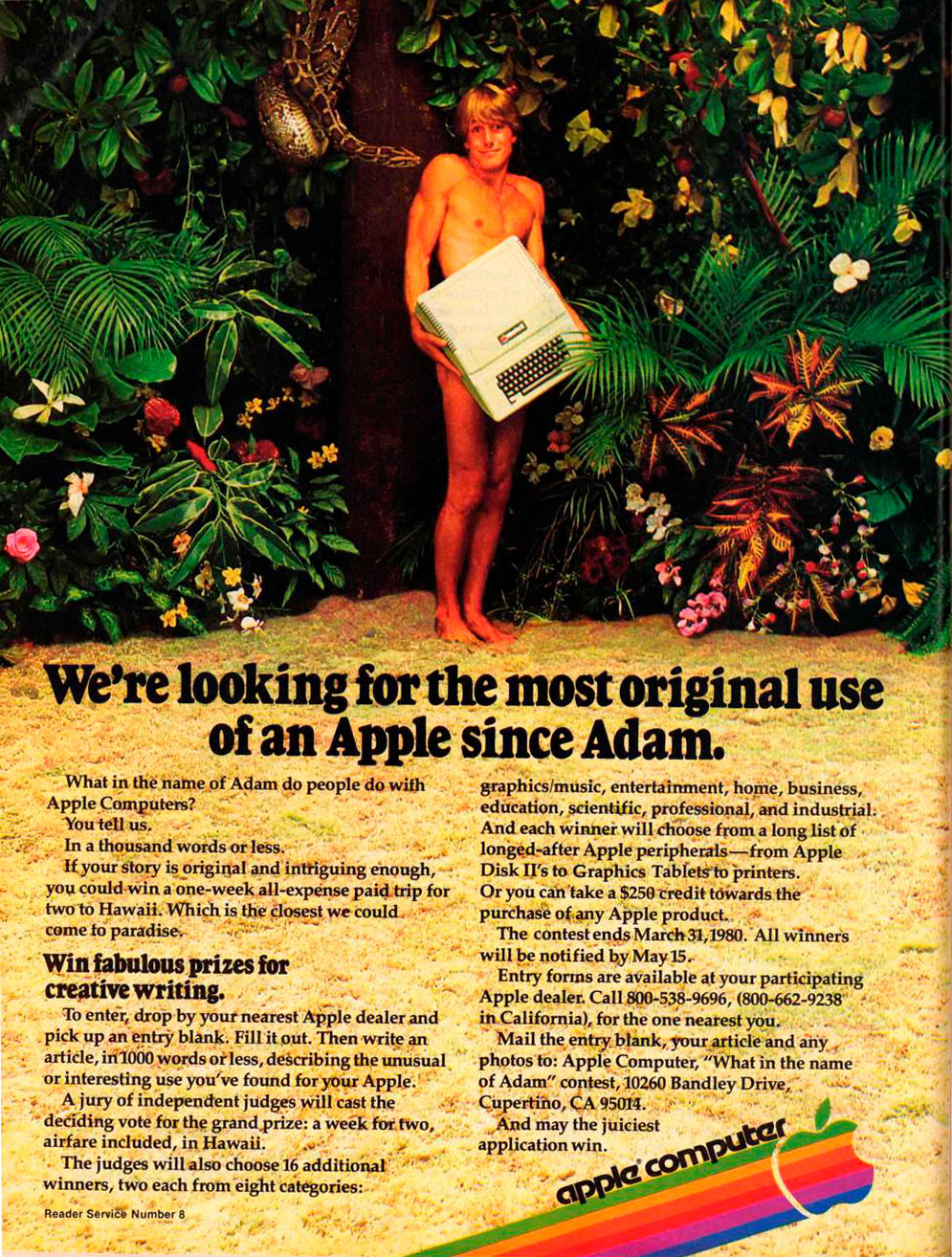

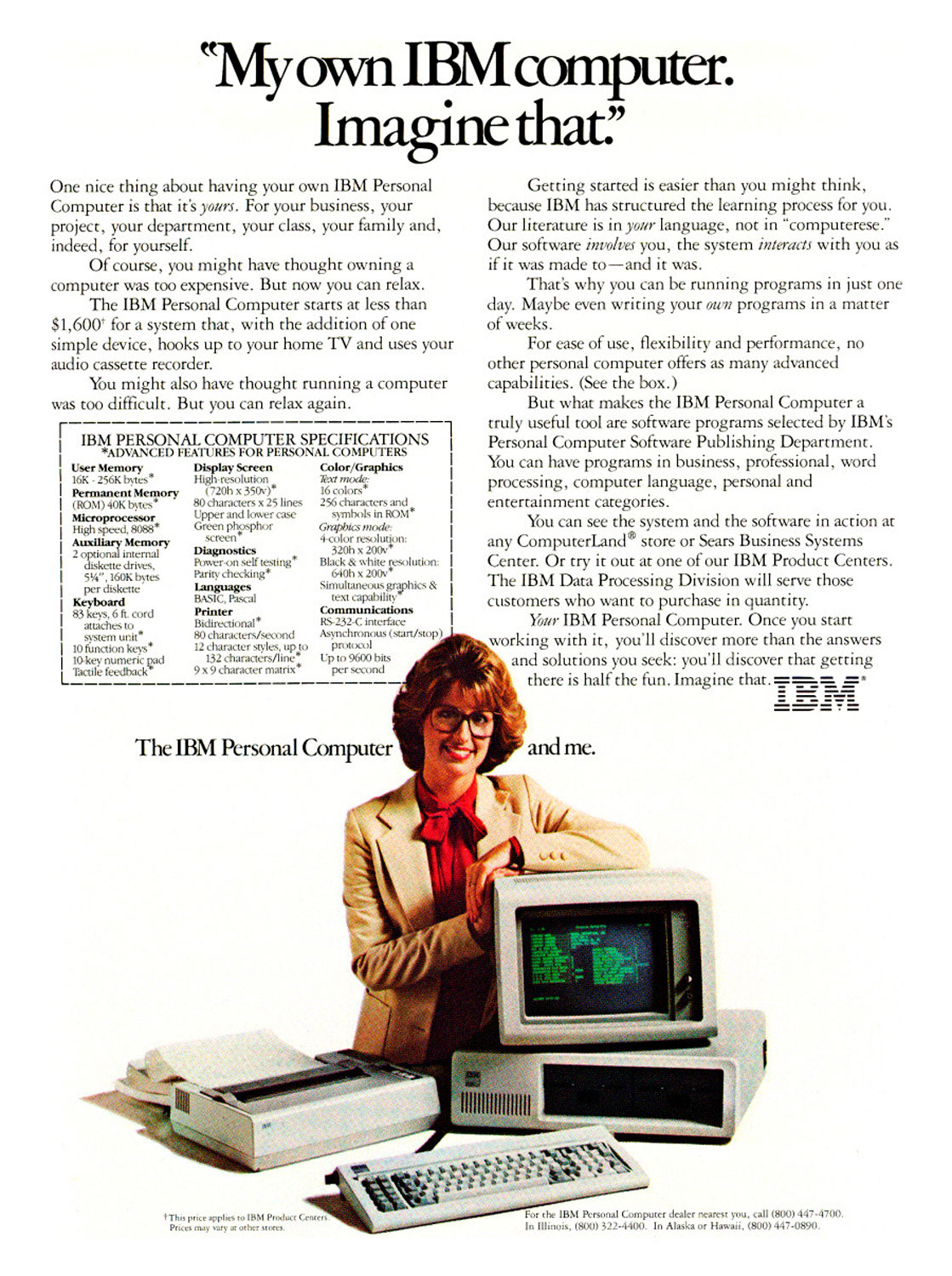

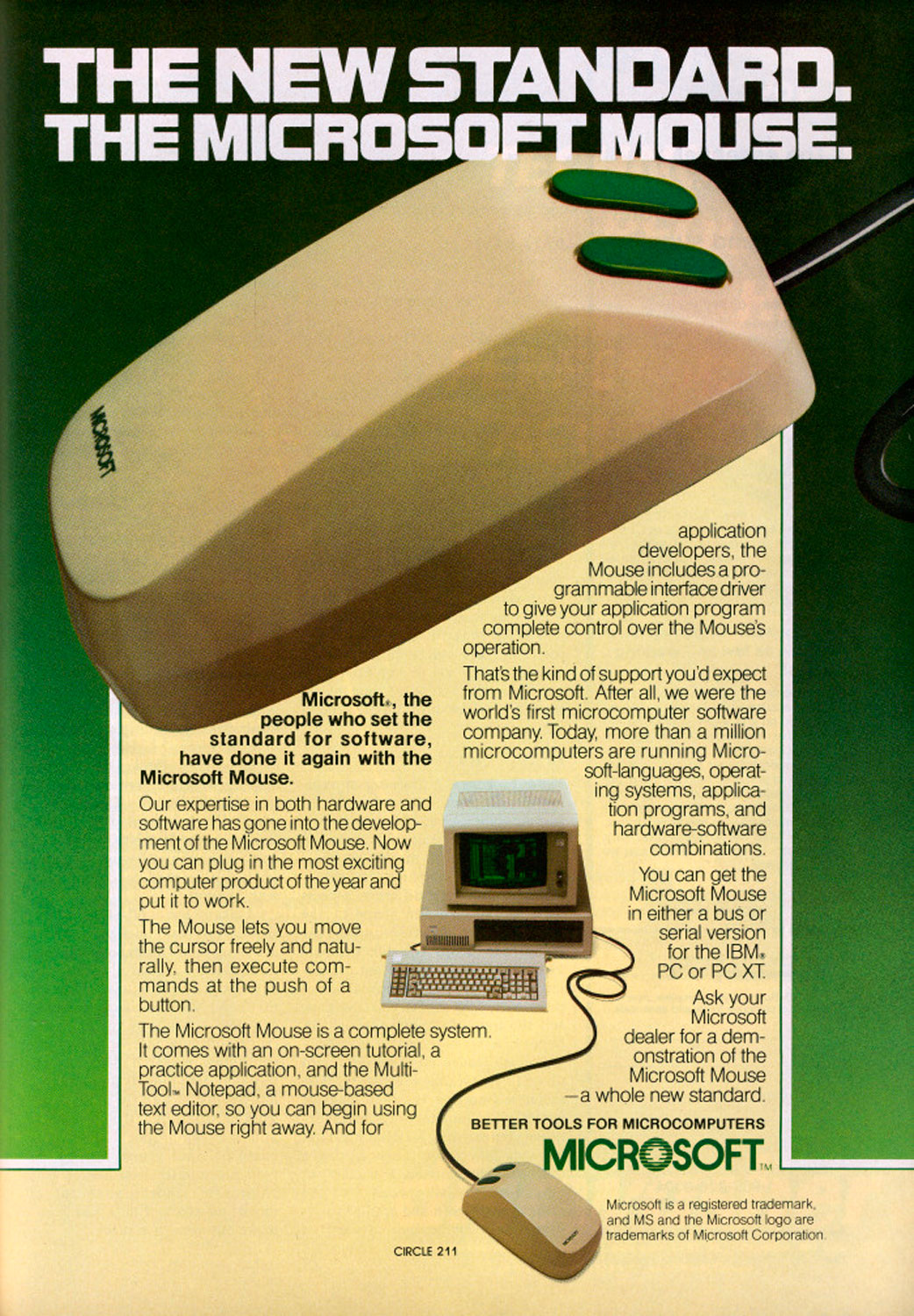

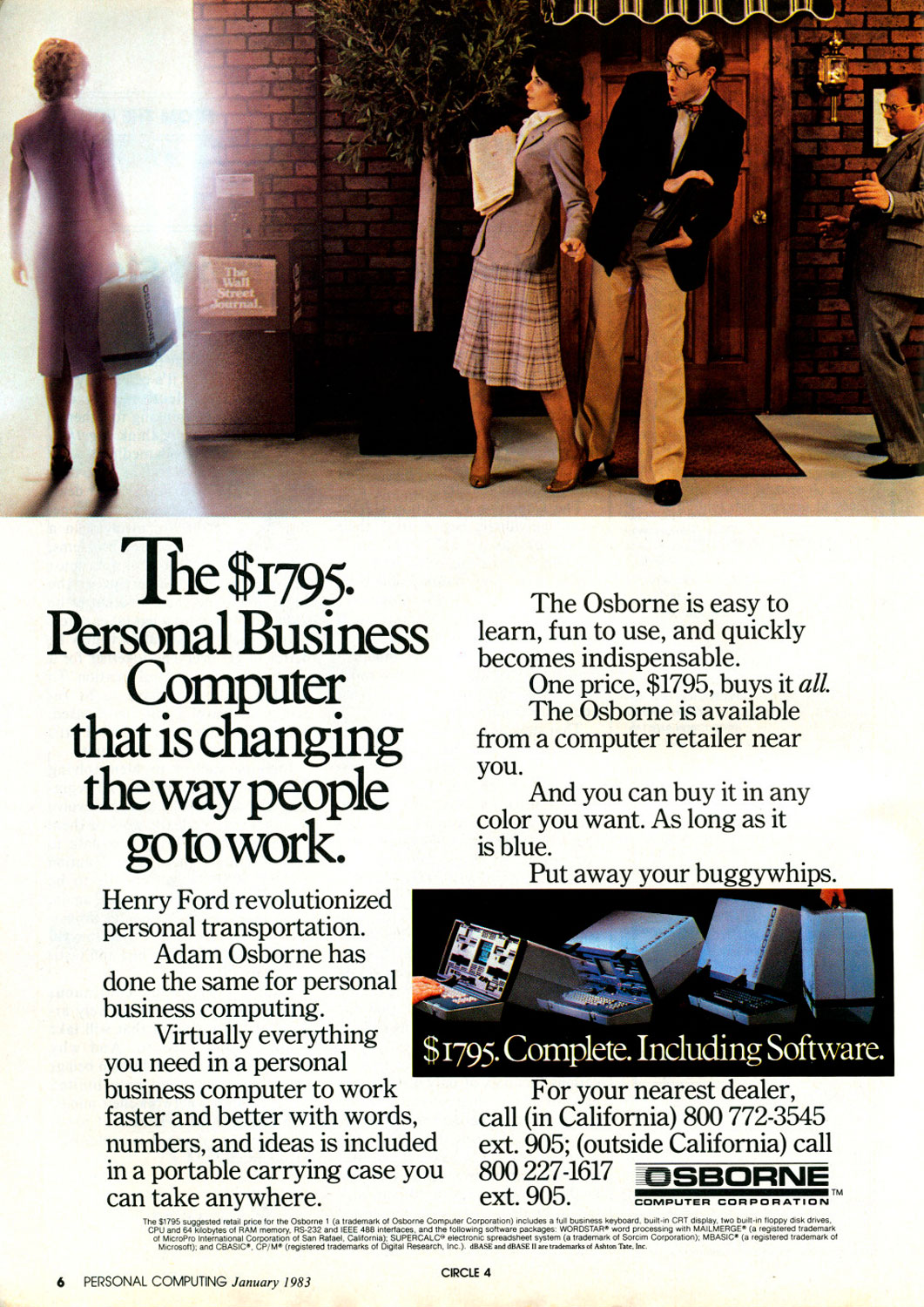

These Vintage Computer Ads Show We've Come a Long, Long Way

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com