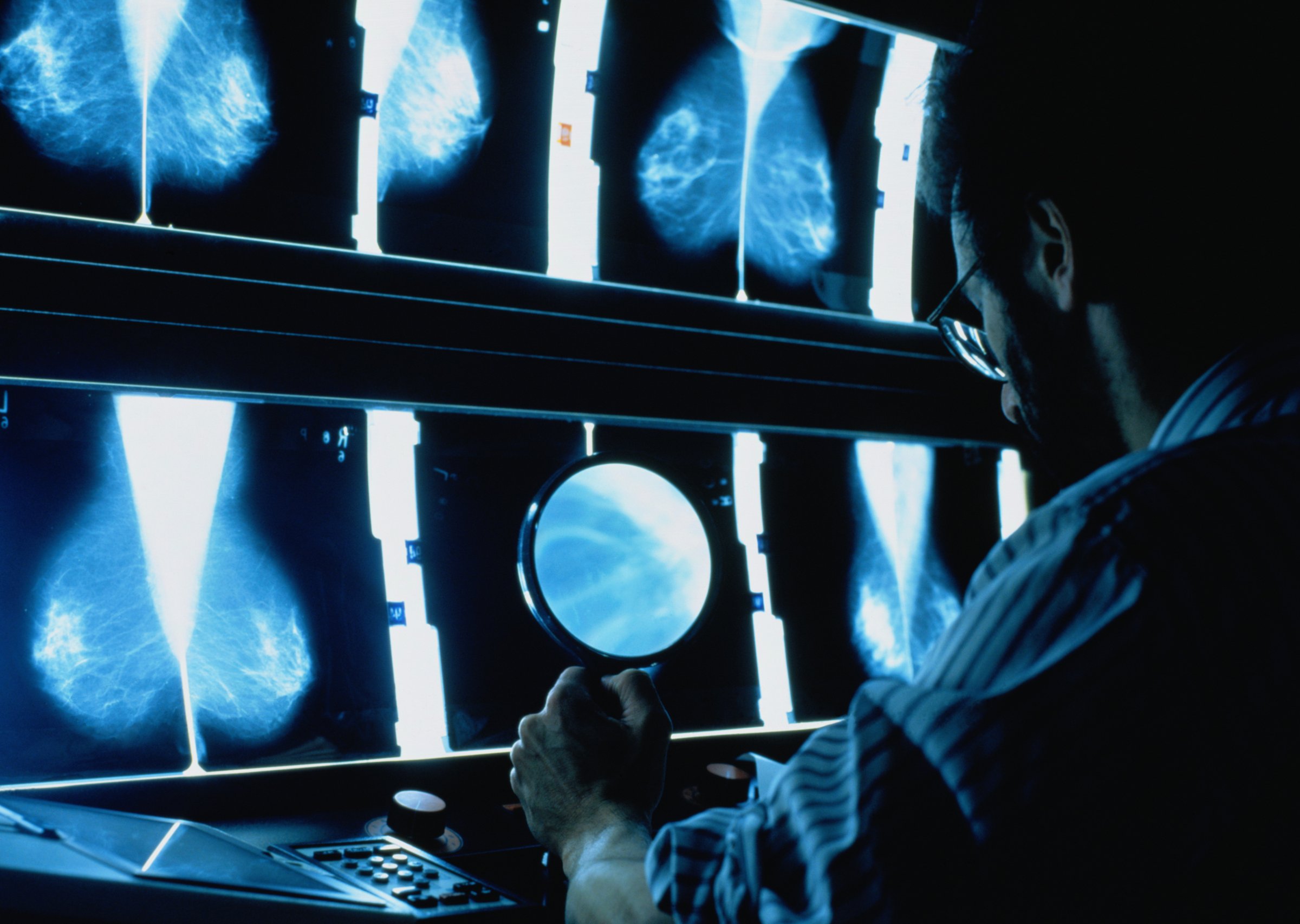

A new study shows that when it comes to diagnosing breast cancer, doctors do not always agree on what the biopsy slides reveal.

Every year, about 1.6 million women in the United States undergo a breast biopsy. In some cases, the biopsy results are obvious; a woman has breast cancer or she doesn’t. But other cases are more uncertain.

According to new research in the journal JAMA, when it comes to less obvious cases, the doctors making the call—pathologists—only agree with outside experts about 75% of the time.

In the study the researchers asked 115 U.S. pathologists to assess 240 breast cancer biopsy slides and make a diagnosis. Their responses were then compared to what a panel of three highly regarded experts determined to be the correct diagnosis.

Fortunately, when it came to diagnosing invasive cancer, there was broad consensus; the pathologists agreed with the panel 96% of the time. When it came to non-cancerous biopsies, the pathologists agreed 87% of the time, but 13% of the time they misdiagnosed.

When it came to more challenging cases—like atypia, where breast cancer cells are abnormal but not cancerous—the pathologists only agreed 48% of the time. In 17% of the cases, the pathologists diagnosed atypia when the expert panel did not, and 35% of the time the pathologists missed the diagnosis.

Another challenging diagnosis is ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), which happens when the cancer is inside the milk ducts but considered non-invasive. When it came to DCIS biopsies, pathologists agreed 84% of the time. Three percent of the time they diagnosed DCIS, and 13% of the time they missed it.

Though the study did not examine the clinical impact of incorrect diagnoses, the findings raise concern about cancer over-diagnosis and over-treatment, as well as missed opportunities to catch true cancer early.

“These findings are disconcerting but perhaps not altogether surprising,” write the authors of a corresponding editorial. (The editorial authors were not involved in the study.) In the real world, pathologists do have the opportunity to consult with others, they note. They conclude that the findings underline the value of having a second opinion in more ambiguous cases.

“The agreement on the diagnosis of invasive carcinoma was quite high, and that should be reassuring,” says Dr. Benjamin Calhoun of the anatomic pathology department at the Cleveland Clinic, who was also not involved in the study. He sees the results as an opportunity to improve continuing medical education for pathologists. “Instead of a lecture from an expert with a few carefully chosen representative images, pathologists need a more ‘hands-on’ experience,” he says, “and the opportunity to compare their diagnoses with an expert panel.”

For now, more research is needed to understand how such findings may be affecting patients.

Before Angelina: Portraits of Breast Cancer Previvors and Survivors

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com