Hi. My name is Carl and I’m a Facebook addict.

(“Hi, Carl!”)

This past weekend, against my better judgment, I got into an unpleasant debate in a Facebook group with a young person whom I do not know. No need to go into details here — let’s just say that by the end, nobody was edified. Much of my weekend got swallowed up in a back-and-forth conversation that generated much more heat than light. I’m embarrassed that I allowed myself to get so thoroughly triggered, and that I kept going back for more, even once I realized that the conversation was not productive. Unfortunately, it wasn’t the first time. But hopefully, this was a “bottoming out” experience, that will force me to create a new relationship with social media: a contemplative relationship rather than a compulsive (addictive) one.

Monks like to say that the heart of monasticism is “I fall down, I get up; I fall down, I get up.” Apparently that’s true for social media as well—at least for me.

As a first step in my “recovery,” I’ve done something I’ve been thinking about doing for a while now. I asked Facebook to convert my personal account (with thousands of friends, most of whom I have never met in real life) and merge it with my existing Facebook Page dedicated to my professional life as a writer and speaker. By doing so, in one fell swoop I have unjoined all the groups I was a member of, and my FB presence is now centered on my work life rather than my personal life. In essence, it’s wiping my slate clean so I can start fresh.

I’ve known a lot of people who have done variations on this: put their Facebook account on ice for Lent, or simply deleted a bloated account and starting fresh with a new one. Since all the conventional wisdom about being a freelance writer nowadays is that one must be on social media, I resisted the temptation to simply nuke my entire Facebook presence (but yes, I was tempted). After all, recovering from a social media addiction can be like recovery from overeating or compulsive spending: the goal is to form a new and healthier relationship with the addictive substance.

So what can someone like you or I do to foster a contemplative relationship with social media, rather than an addictive one where too much time is spent online or too much arguing and debate happens there? Here are a few thoughts on the matter, and I’d be curious to hear from others about what they think.

1. Follow the Rules. Facebook recommends its users only initiate (or accept) friend requests with “people who know you well, like friends, family and coworkers.” In a similar way, LinkedIn recommends only sending “Invitations to connect” to people “you know and trust.” Clearly, there’s no hard and fast rule about what this means — but in the past, I was too quick to accept friend requests from anyone who wandered by. Not only has this meant I’ve had to spend lots of time reading posts that weren’t relevant to my life, but also that I’ve had to deal with too many spammers and trolls. I’m an American and so I’m susceptible to our national dogma that “more is better” — but on Facebook, more friends is not necessarily better. Quality, not quantity.

2. Know the difference between an account and a page. Facebook frowns on using one’s personal account to promote a business, and suggests that if you have a product or a service you want others to know about — even if it’s just a blog — that you set up a public page to get the word out. I’ve had a public page for some time now, enabling me to keep my personal and professional lives separate (posting links to my blog on my page, pictures of my cats on my account) but the lines have often seemed too blurry. But it seems to me that Facebook guidelines can sort this out: the personal account is for a relatively small number of close friends, family and co-workers. The page is for everybody.

3. Be careful about joining groups. My unpleasant conversation this weekend took place in a group, and I should have known better: the group where it happened embodies a certain perspective and I was arguing for a point contrary to that position. No wonder it ended badly. But even when it’s all peace and love in a group, it can be the kind of setting where someone like me can invest a lot of time agreeing with people who agree with me. And then the weekend’s gone and the lawn never got mowed.

4. Manage the timeline. I have some family and friends who I love dearly, but in real life we don’t talk politics. So why do I allow myself to read their political rants on Facebook? All it does is make my blood boil, and there’s no point arguing back — the few times I’ve tried, it always just escalates. Facebook allows you to remain a friend with someone but to disallow their posts from showing up on your timeline. Obviously, if you want to stay in touch with someone this might not be an ideal option, but it can be a great way to keep loved ones in your FB circle while also protecting your blood pressure.

5. Make use of Facebook’s “Friends List” feature. Some people are close friends. Others, just acquaintances. Facebook allows us to invisibly mark each connection accordingly (we can also tag family members and set up custom lists). Then, when we post something, we can decide if the general public sees it, or just friends/acquaintances, or just close friends. It’s a good way to manage who gets to see pictures of the new kitten and who gets to read about our deepest hopes and fears.

6. Disengage. Obviously, from what happened this past weekend, I’m still working on this one. But it’s a simple principle: if someone posts something I vehemently disagree with, I don’t have to post a clever or snarky reply. I’m sorry to say it, but I find it’s all too easy to get argumentative with people online, usually about something I feel passionate about — but online arguing rarely does anybody any good. If I must post something, I’m going to try to be as objective/factual as possible, state my case, and then let it go. If the other person(s) tries to pick a fight with me? Disengage.

7. Forgive. When I make a mistake online — whether spending too much time on Facebook, or getting caught up in an unpleasant exchange — I have to remember to forgive myself; after all, we all do foolish or hurtful things from time to time. And when it involves somebody else, I need to forgive them too, if necessary. Forgiveness doesn’t mean I can avoid making positive changes — but it does mean I can let go of the sting of old mistakes when what’s done is done. I once heard a recording of Thomas Keating where he suggested that remorse is healthy only for about 30 seconds! The point behind remorse or contrition is that it impels us to make positive changes. After that, it has served its purpose and needs to be released. Forgiveness is how such release takes place.

8. Pray. It’s humbling for me to admit that, after having a Facebook account for six years, I still don’t do a very good job at limiting the amount of time I spend on it, or maintaining boundaries between my personal and professional lives, or avoiding getting into useless debates and arguments. Well, I’m only human: “I fall down, I get back up.” But maybe the single best strategy is to remember the Jesuit principle that we can find God in all things. Yes, even social media. If I can bear in mind that my time on Facebook or Twitter or Patheos is time spent in the presence of God, maybe that can help me to be a bit wiser, a bit more loving, a bit more present. Which leads to my final and most important point:

9. Be Silent. I’m still working this one out, but it’s becoming obvious to me that silence needs to be an ingredient in my social media engagement. I need time off from Facebook, whether that means a Sabbath day when the computer never gets turned on, or a “Great Silence” period of eight hours or so each evening/night to give it a rest. Just as important, silence needs to be an element of how I am present online: this is a corollary to #6 above, where I can choose to respond to inflammatory or triggering posts with the generosity of silence rather than the intensity of debate.

Okay, this is a work in progress. I’d love to know your thoughts: what do you do to maintain a contemplative relationship with social media?

Carl McColman is a life-professed Lay Cistercian — a layperson under formal spiritual guidance at a Trappist monastery. He is also an instructor with Emory University’s certificate program in creative writing, and regularly teaches the craft of nonfiction, as well as writing and journaling as a spiritual practice.

This article originally appeared on Patheos.

Read more from Patheos:

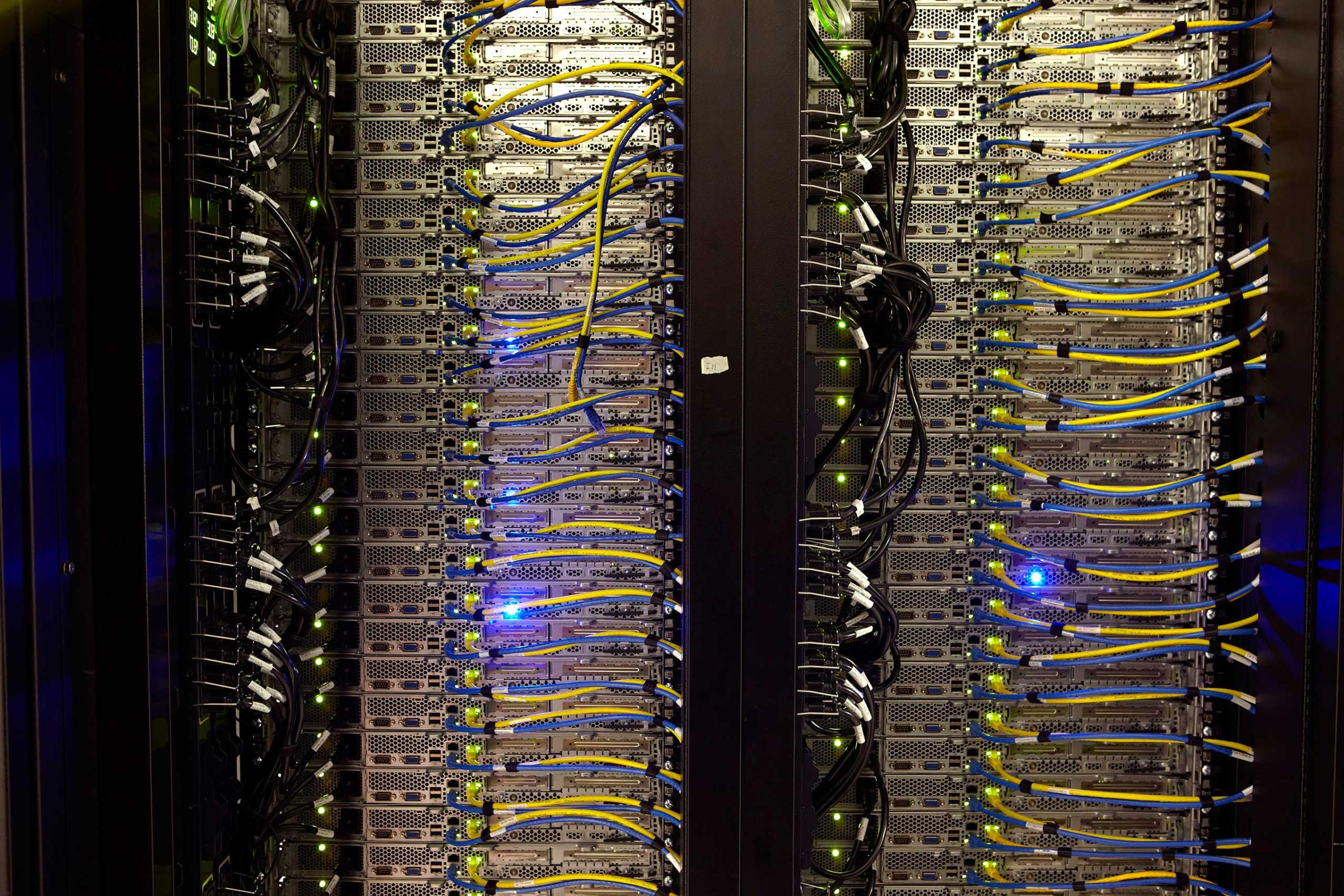

A Glimpse Inside A Facebook Server Farm

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com