According to a recent report by an Alabama-based civil rights group, the Southern Poverty Law Center, the number of extremist and anti-government “patriot” groups in the United States declined to around 2,000 in 2013 — after reaching an all-time high of almost 2,400 in 2012. Rather than a positive development, however, the SPLC notes that the lower number of hate groups might well be the result of the mainstreaming of far-right ideas into state legislation across the U.S.

But even if the number fluctuates by a few hundred year over year, the fact remains that Neo-Nazis, “Christian Identity” cults, white supremacist militias and other anti-Semitic, anti-foreign nativist groups exist in all 50 states.

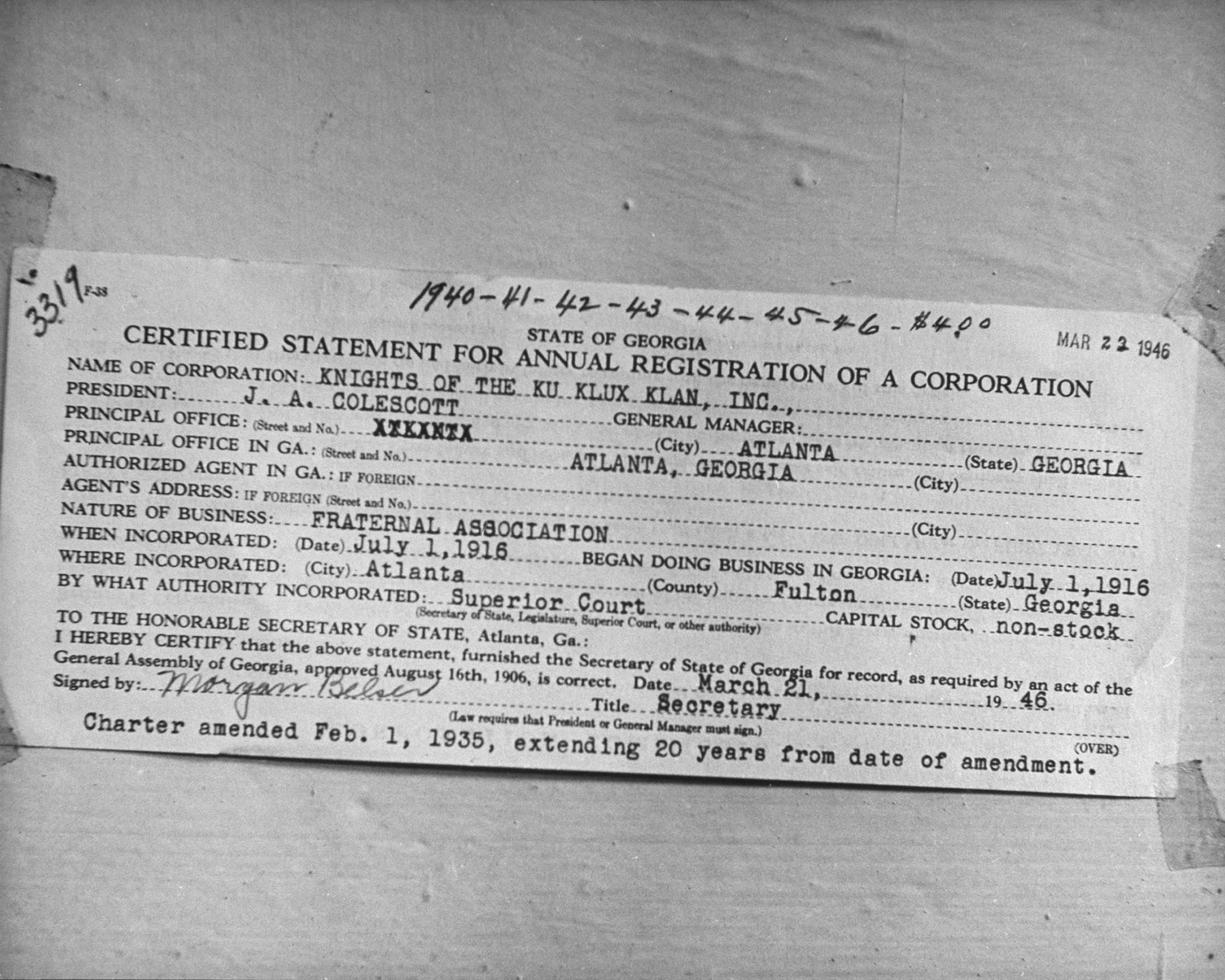

When it comes to extremist groups in America, of course, the longest-lived and most readily identifiable remains the Ku Klux Klan, which has been operating at varying degrees of influence and strength for close to 150 years. Hundreds of Klan groups are actively working and recruiting in the U.S., with more than two dozen in Texas alone. The KKK’s fortunes as a cultural and political force have waxed and waned over the decades, with Klan membership peaking in the 1920s, during the era of the “Second Klan.” (The First Klan, in the post-Civil War South, lasted from 1865 to 1874; the Second Klan from 1915 until about 1944; and the Third from roughly the end of WWII until today.)

The Klan claimed literally millions of members at the height of the Second Klan era; today, Klan watchers estimate that number to be fewer than 10,000. The good news is that’s a precipitous drop, to say the least, in the number of people officially associated with the KKK; the bad news is that many thousands of Americans who might have joined the Klan in the past have instead aligned with a host of extremist splinter groups, militias and other organizations, making the far-right fringe as dangerous as it’s ever been.

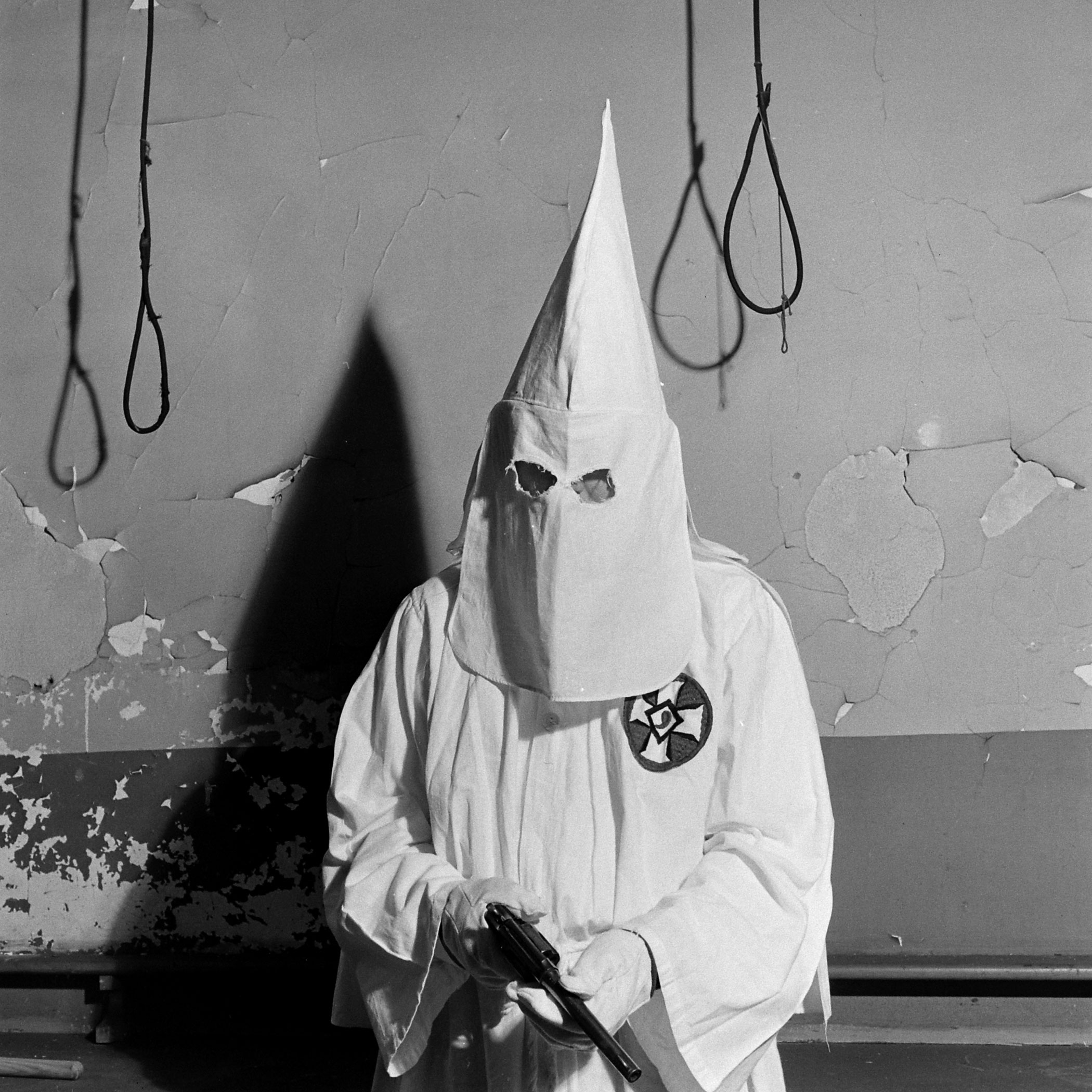

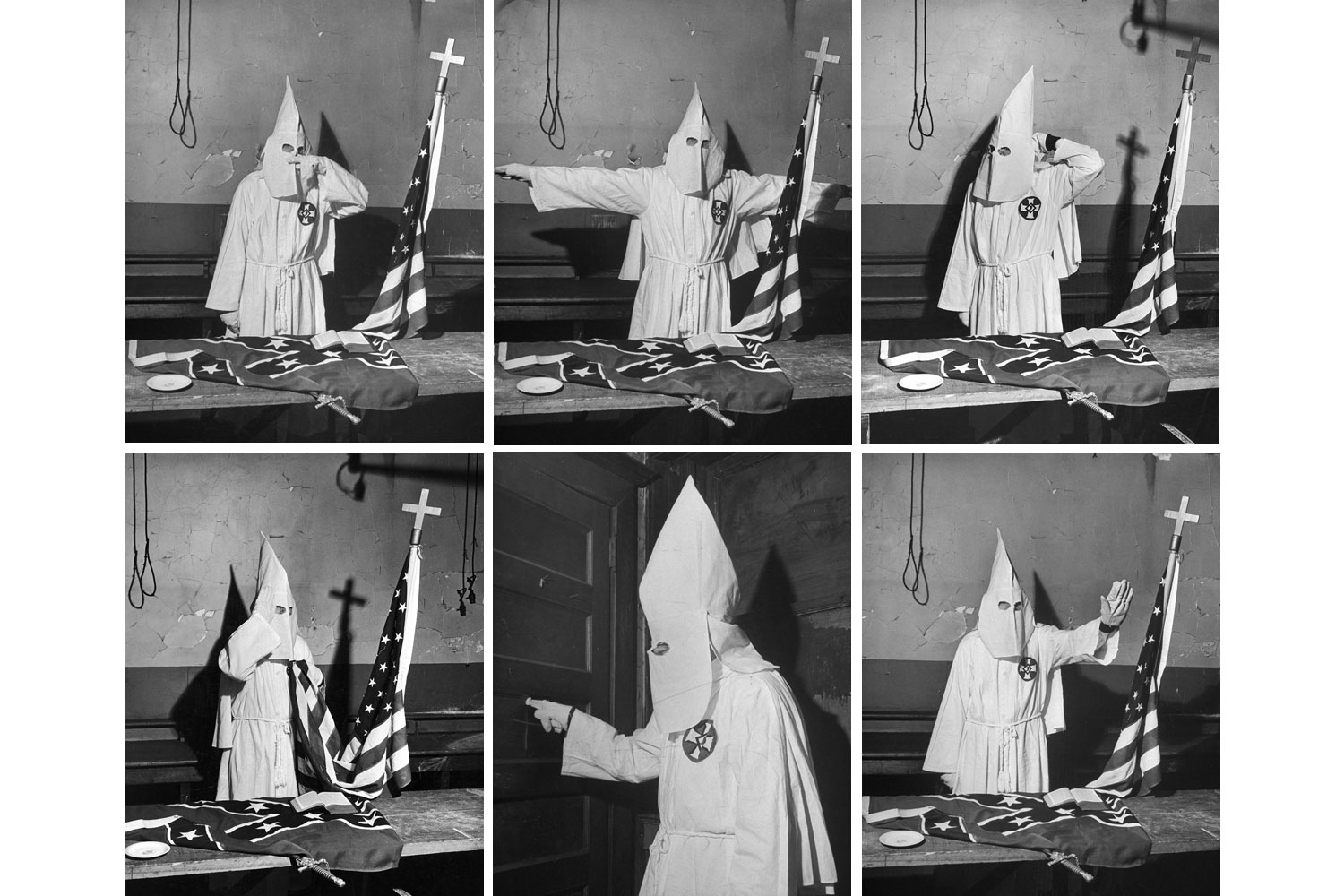

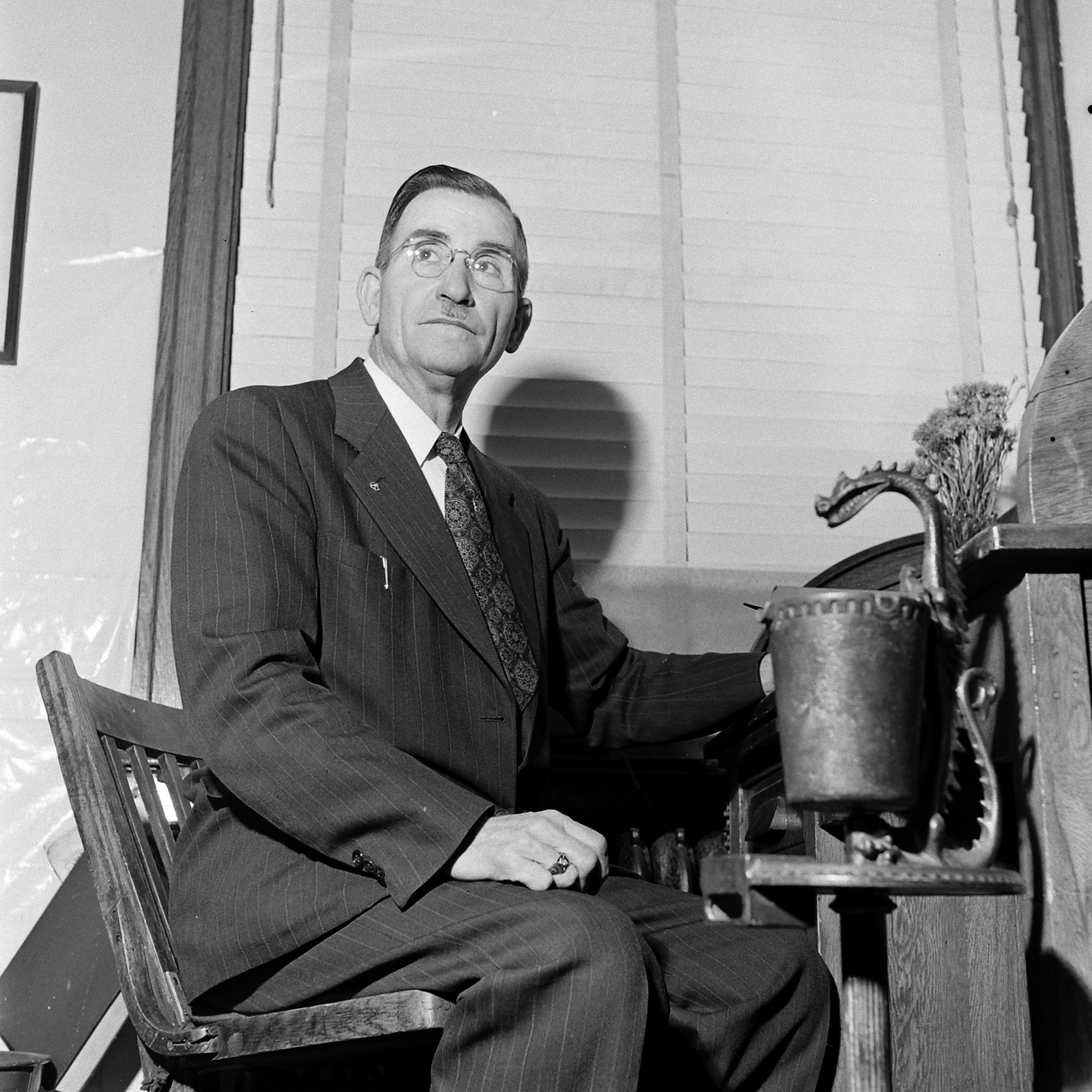

In May 1946, LIFE magazine ran a series of remarkable pictures from a Klan initiation in Georgia, at the start of the Third Klan era. Titled “The Ku Klux Klan Tries a Comeback,” the article noted that the KKK pledged initiates “in a mystic pageant on Georgia’s Stone Mountain.” The language that accompanied photographer Ed Clark’s pictures, meanwhile, made clear that, as newsworthy as the story of this particular initiation might have been, LIFE’s editors considered the figures in their white robes and hoods to be rather laughable — if their rhetoric and arcane, pseudo-mystic shenanigans weren’t so unsettling.

On the evening of May 9 at 8 p.m. a mob of fully grown men solemnly paraded up to a wide plateau of Stone Mountain outside Atlanta, Ga., and got down on their knees on the ground before 100 white-sheeted and hooded Atlantans. In the eerie light of a half-moon and a fiery cross they stumbled in lockstep up to a great stone altar and knelt there in the dirt while the “Grand Dragon” went through the mumbo jumbo of initiating them into the Ku Klux Klan. Then one new member was selected from the mob and ceremoniously “knighted” into the organization in behalf of all the rest of his fellow bigots.

This was the first big public initiation into the Klan since the end of World War II. It was put on at a carefully calculated time. The anti-Negro, anti-Catholic, anti-Semitic, anti-foreign, anti-union, anti-democratic Ku Klux Klan was coming out of wartime hiding just at the time when the CIO and the A.F. of L. were starting simultaneous campaigns to organize the South. . . . But it is doubtful that the Klan can become as frighteningly strong as it was in 1919. One indication of the Klan’s impotence was its lack of effect on Negroes, who were once frightened and cowed by the white-robed members. More than 24,000 Negroes have already registered for next July’s primaries in the Atlanta vicinity alone, where the Stone Mountain ritual was held.

As mentioned in one of the captions in the gallery above, the Stone Mountain ceremony was put off several times during the preceding year because of wartime sheet shortages. Or at least that’s what LIFE reported at the time.

The magazine also made a point of characterizing the garb and actions of members at Klan meetings (slides #10 through 15) as both creepy and pathetic. “Childish ritual and secretiveness,” the magazine noted, “have always been the great attractions for the kind of people who make good Klansmen.”

The more things change. . . .

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com