Twenty-five years ago, a new film reinvigorated a genre and seemed to point a way forward. Pretty Woman, released on March 23, 1990, established Julia Roberts, already an Oscar nominee for her role in Steel Magnolias, as the queen of the romantic comedy. But perhaps more resoundingly, it established the “high-concept”—the story that could be told in a clear, concise logline—as the order of the day for the genre. Romantic comedies of the past had relied on little but chemistry. Pretty Woman established the appeal of extraordinarily high bars to clear for the couple at a film’s center. It was an innovation that brought the genre short-term gains, but long-term obsolescence.

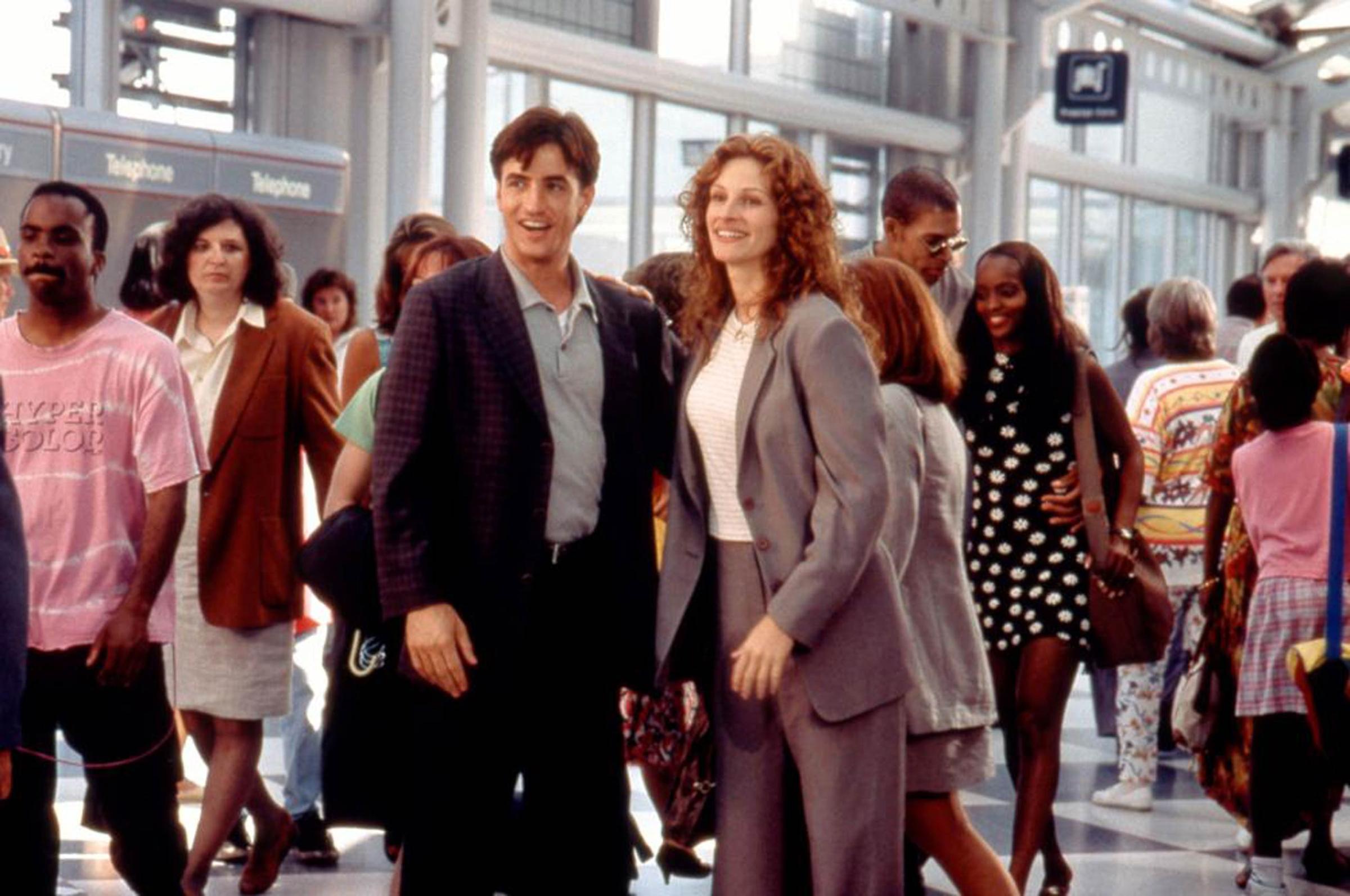

It’s hard to give Pretty Woman too much credit for its originality, considering that, at its center, it’s yet another revision of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (which also provided grist for the musical My Fair Lady). And yet there’s a real frisson to the story of Los Angeles prostitute Vivian (played by Roberts), who is taken on as a client by wealthy traveling businessman Edward (Richard Gere) and taught to fit into polite society. After a few obstacles, the pair end up wiser about one another’s worlds, and, more importantly, together. It seems quotidian today, after not merely endless replays on cable but multiple films that got even closer to fantasy, but the Pretty Woman plot is so outlandish as to be a little funny, taken on its own: Edward realizes, after only a couple of days with Vivian, that he no longer cares about his job and decides to tank a business deal. Sure! The whole thing was significantly softened up from the first draft, in which Vivian was a crack addict whom Edward leaves at film’s end to return to his girlfriend. The final version was much cleaner, if much less realistic.

The revision process made Edward and Vivian into guileless figures able to overcome any obstacle, but not every audience member was along for the ride. Wrote TIME’s critic Richard Corliss: “No one has yet made a romantic comedy in which, say, a toxic-waste dumper falls for a terrorist hijacker. […] But Pretty Woman comes close to finding the least admirable characters to build a feel-good movie around.” Corliss went on to cite, as evidence against the movie, its fusing of utterly predictable beats with age-of-irony noxious characters. His headline, summing up the movie’s decadence and its familiarity, was perfect: “Sinderella.” But this merger of old and new worked, to many moviegoers, in the movie’s favor. Roberts was nominated for her second Oscar, this time for Best Actress, for Pretty Woman; the film came in fourth in the domestic box-office tally that year, a rarity for a film released outside summer or the holidays. The number-one hit of 1990 was Ghost, a romantic drama that assayed the only barrier greater than that between prostitute and john.

Roberts’s post-Pretty Woman years were a series of ups and downs: She worked in several films that sought to replicate whatever it was that had made her 1990 turn so electric. When Corliss wrote about Roberts’s 1991 film Sleeping With the Enemy, he indulged suspicions that “Roberts has been more lucky than smart,” noting “an emptiness at the core of her charm.” That perceived emptiness allowed Roberts to outlast the other actresses he cited as her superiors, including Winona Ryder and Michelle Pfeiffer, as she brought much willingness and little spiky resistance to projects whose main draw was an out-there conceit; in more generic rom-coms, like I Love Trouble, she added little (reviewing that film, Corliss called Roberts “a Lamborghini that few people know how to drive”). And the less said about her mid-1990s experimentation with period drama, in Michael Collins and Mary Reilly, the better. But once Roberts embraced her role as a path-breaking star of a very specific sort of movie, she rose again.

In My Best Friend’s Wedding, Roberts played a near-demonic figure, a restaurant critic bent on sabotaging the nuptials of her pal so that she could cash in on a marriage pact they’d made years before. She was unsympathetic in the extreme—and, more notably, playing her part in a romantic comedy with a concept so high it could give the casual viewer altitude sickness. It was a hit, and restored Roberts to prominence in a genre she was helping to define with her willingness to go to the edge. A few years later came Notting Hill, in which Roberts played a world-famous actress crossing the fame divide to date a bookstore owner, and Runaway Bride, in which she re-teamed with Gere to play a woman terrified of marriage. Gere was the journalist profiling her…who ends up wanting to marry her, despite her impulses and his job.

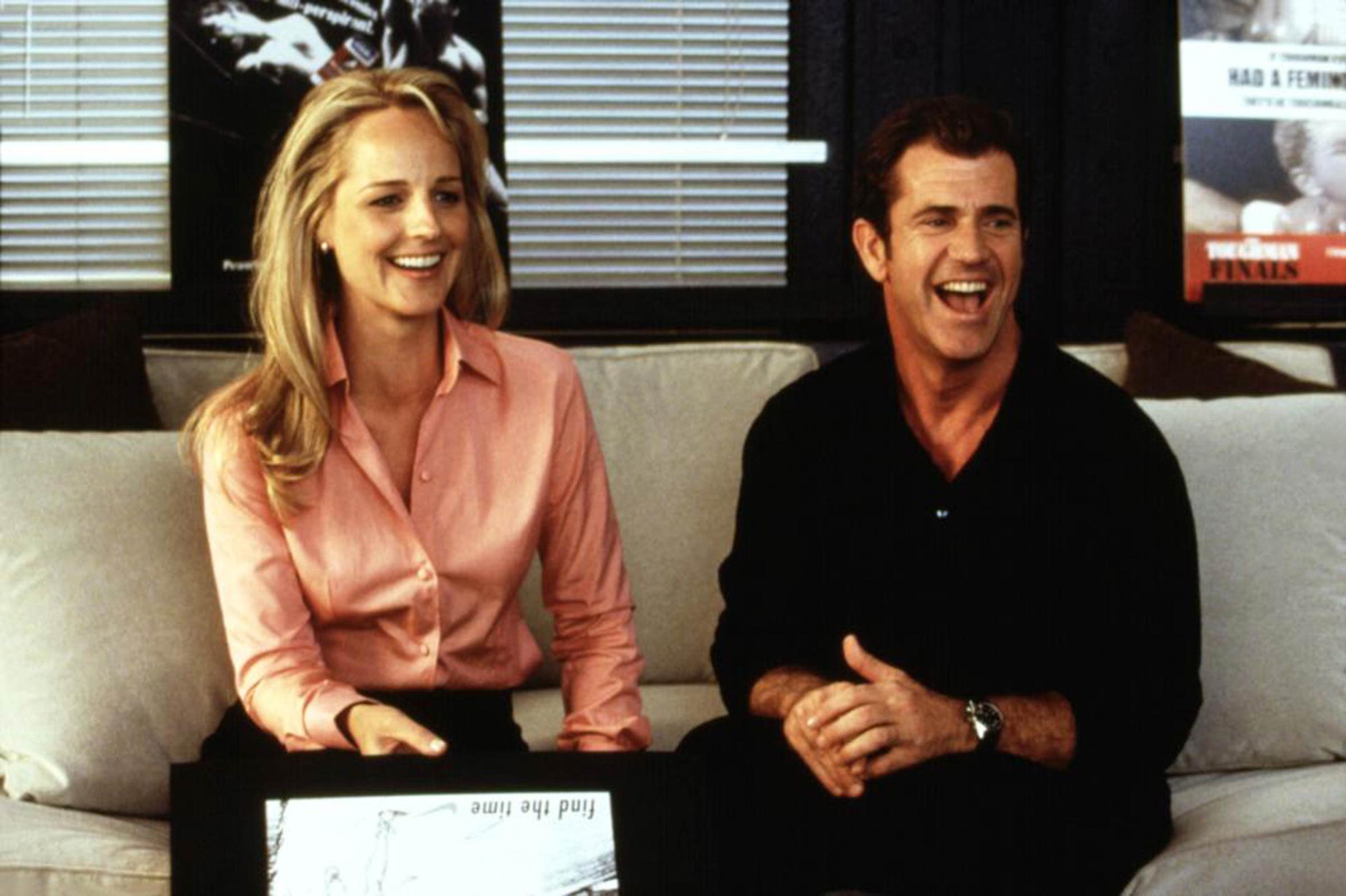

Roberts’ willingness to take on relatively outré plots, at least for a genre historically designed to get men and women together by film’s end with only the cutest of obstacles, and her ability to sell lines with a coltish smile or a quivering upper lip, made her a star. It also changed the game. In 2007, TIME’s Belinda Luscombe reported on the end of the movie romance, citing Notting Hill writer Richard Curtis, who said: “[I]f you write about two people falling in love, which happens about a million times a day all over the world, for some reason or another, you’re accused of writing something unrealistic and sentimental.” In 2007’s big-hit movie romance, Knocked Up, one sees the fundamentals of a Roberts hit: A preposterously unbridgeable divide crossed, ultimately, against the bounds of good sense. Katherine Heigl, that film’s star, criticized the film’s writing for making her seem “humorless and uptight.” She was no less uptight than was Roberts doggedly seeking to ruin a wedding or, 25 years ago, refusing kisses on the mouth, but the blueprint of bizarre-seeming boundaries between stars was now so firmly established as to seem invisible. Heigl may not have thought the divide between the characters made Knocked Up funny, but the laughing audience didn’t notice.

Today, the romantic comedy is yet more moribund than it was in 2007; after the flukey success of Knocked Up and Roberts’s transition into dramas, no one has taken the crown. Jennifer Lawrence and Emma Stone have both done one fairly down-to-earth entry (respectively, Silver Linings Playbook and Crazy, Stupid, Love) and then had their fill. Maybe that’s for the best. For a ten-to-15 year span following Pretty Woman, the genre was defined by more-and-more excessive spins on how to keep stars apart. (In 2005, the putative rom-com queen filed her last entry in the genre with Just Like Heaven, in which she played a ghost. It was Ghost… but a comedy, and a signal that the high-decadent phase of romantic comedy had reached its terminus.) As the field lies fallow, maybe a new Roberts will assert herself and indulge audiences’ taste for baroque obstacles and unrealistic final pairings. Or maybe there’s one more pairing left in Roberts and Gere—though given the places they’ve been, it’s hard to imagine where they’d go next.

One possibility, suggested by the success of lower-fi films like Silver Linings Playbook, is that a quarter-century may be long enough for the trend started by Pretty Woman to last—and the rom-coms of the future may have more to do with conditions found on planet Earth.

Read TIME’s original review of Pretty Woman, here in the TIME Vault: Sinderella

Read next: 12 Fascinating Facts to Celebrate Pretty Woman’s 25th Anniversary

See the 20 Most Successful Romantic Comedies

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com