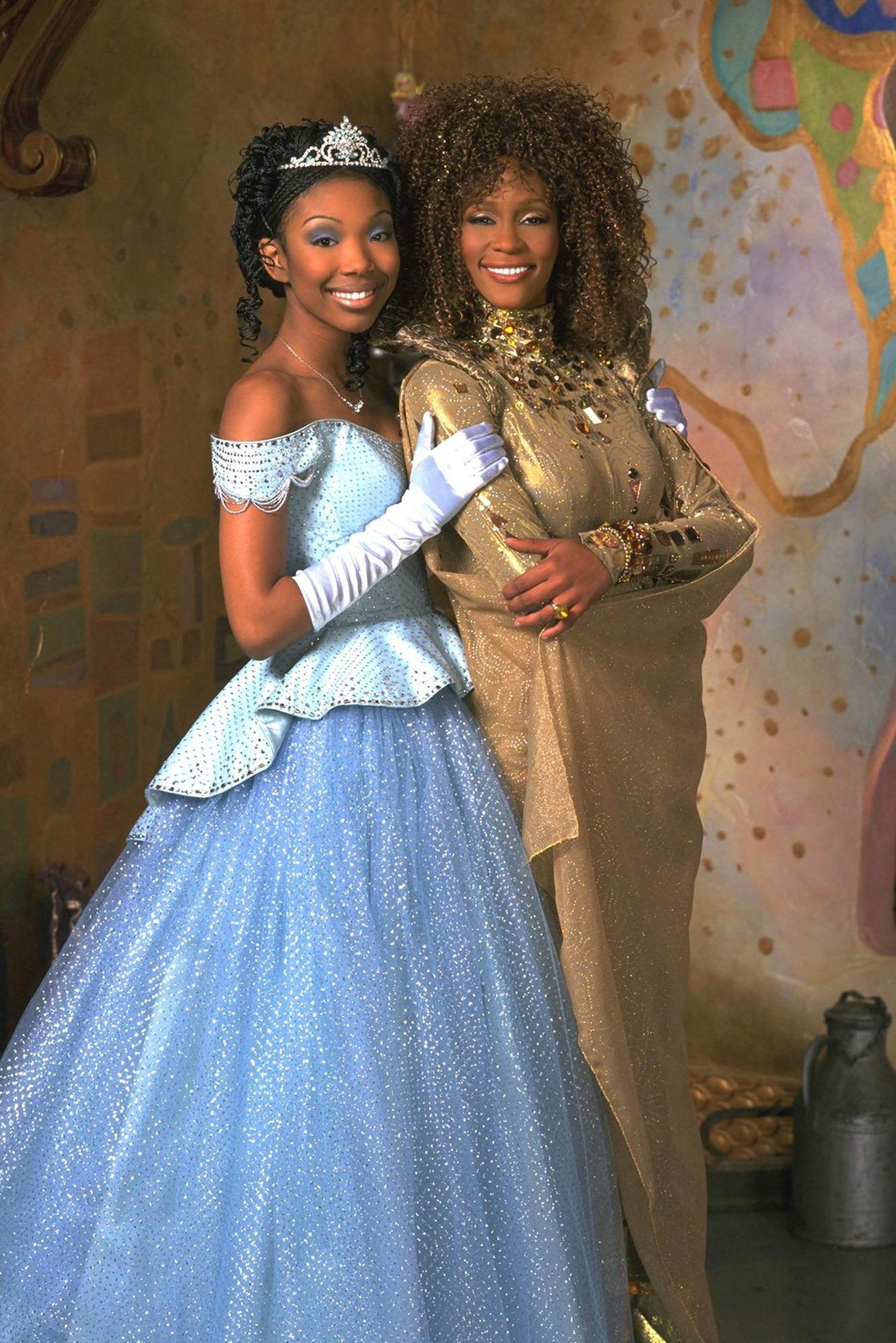

The Cinderella story, codified by Charles Perrault as Cendrillon in 1697, has been a movie staple since the beginning of the medium. That prime cinemagician Georges Méliès conjured up a Cendrillon in 1899, employing trick photography to turn a rabbit into a footman, rats into coachmen and a pumpkin into a carriage. The role was played in 1914 by Mary Pickford, the movies’ first star actress, and, in a gender-bending switch, by Jerry Lewis in the 1960 CinderFella. Julie Andrews graced Rodgers and Hammerstein’s 1957 TV musical version, remade in 1966 with Lesley Ann Warren and in 1997 with Brandy. Drew Barrymore brought feminist spark to Ever After: A Cinderella Story in 1998; Anne Hathaway endured ogres and snakes in the 2006 Ella Enchanted. A few months ago, in Into the Woods, Anna Kendrick’s Cinderella found to her chagrin what happens after “happy ever after.”

But if the Cinderella fable has an owner and chief curator, it’s Walt Disney. Of the hundreds of movie versions, his 1950 animated feature is the most popular and best remembered. All these decades later, the studio expects only good luck from the Friday-the-13th release of a lavish live-action version directed by Kenneth Branagh, adapted by Chris Weitz and starring Lily James as Cinderella and Cate Blanchett as the stepmother Lady Tremaine. Most of the industry touts are forecasting at least a $60-million opening in North American theaters.

The Disney fascination with the sooty heroine, the Prince and the glass slipper goes back to Walt’s earlier days as a cartoon producer. He was just a kid when he made his first Cinderella as a Laugh-O-Gram in his Kanas City studio. The movie premiered on Dec. 6, 1922, the day after Walt turned 21 — the same age as his invaluable pal Ub Iwerks, who animated and directed the movie (and, later, the first Mickey Mouse cartoon, “Steamboat Willie”). Running a brisk 7 min. 23 sec., Disney’s first Cinderella is the old fable transplanted to the Jazz Age, with physical comedy trumping dreamy romance.

The plucky orphan, “whose only friend was a cat,” gets bossed around by “two lazy and homely step sisters” — but no wicked stepmother. The Prince, “a wonderful fellow” whose only friend is his little white dog, is first shown hunting bears by shooting them in the butt (early Disney is a trove of ass gags). The Prince schedules a ball, for “Friday the 13th,” but Cinderella’s stepsisters say she can’t go. A crone-like Fairy Godmother shows up to give the girl a snazzy flapper gown and change a trash can (not a pumpkin) into a Model T; the black cat is her chauffeur. It’s love at first sight for the Prince; they dance the night away to the strains of a Paul Whiteman-like jazz band. At midnight Cinderella flees, leaving her glass slipper. The chase is on; the Prince finds her and embraces her, as his dog does her cat. “And they lived happily ever after.”

The 1950 version was the studio’s first full animated feature since Bambi eight years earlier, and it rescued the Mouse House from near-bankruptcy. Cherished for the hit songs “A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes” and “Bibidi-Bobbidi-Boo,” it is also the least faithful to its source. About half of the 1hr. 14min. movie is devoted to the shenanigans of the heroine’s closest companions, a quartet of talking mice, and their slapstick battles with Lady Tremaine’s obnoxious cat Lucifer. The feline role reversal from the 1922 cartoon may have been Disney’s attempt to mimic the Hanna-Barbera Tom and Jerry cartoons, which won five Oscars for Best Animated Short between 1943 and 1948 — the very prize Walt had previously monopolized with 10 wins between 1932 and 1942.

The Prince is virtually AWOL in the 1950 movie; he doesn’t appear until two-thirds of the way through and speaks only a few words. (In the duet “So This Is Love,” his singing voice is supplied by future talk-show host Mike Douglas.) He is mainly a pawn in the machinations of his temperamental father the King and a fussy Grand Duke. The big drama is again with the critters: Will the mice Jaq and Gus will be able to lug a key up to the attic that imprisons Cinderella? Whatever its appeal to many generations of children, this is one Disney feature that today looks coarse and ill-conceived.

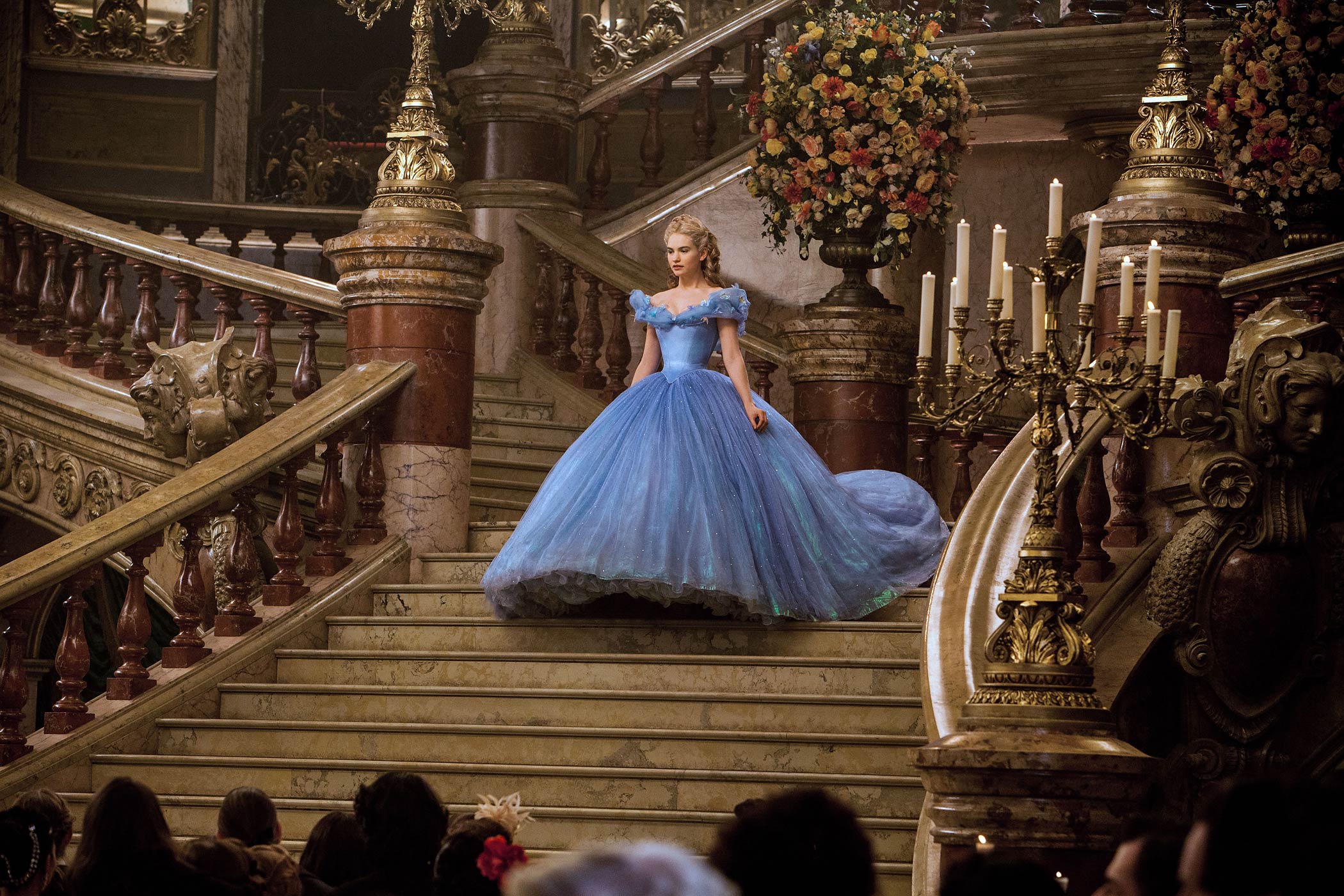

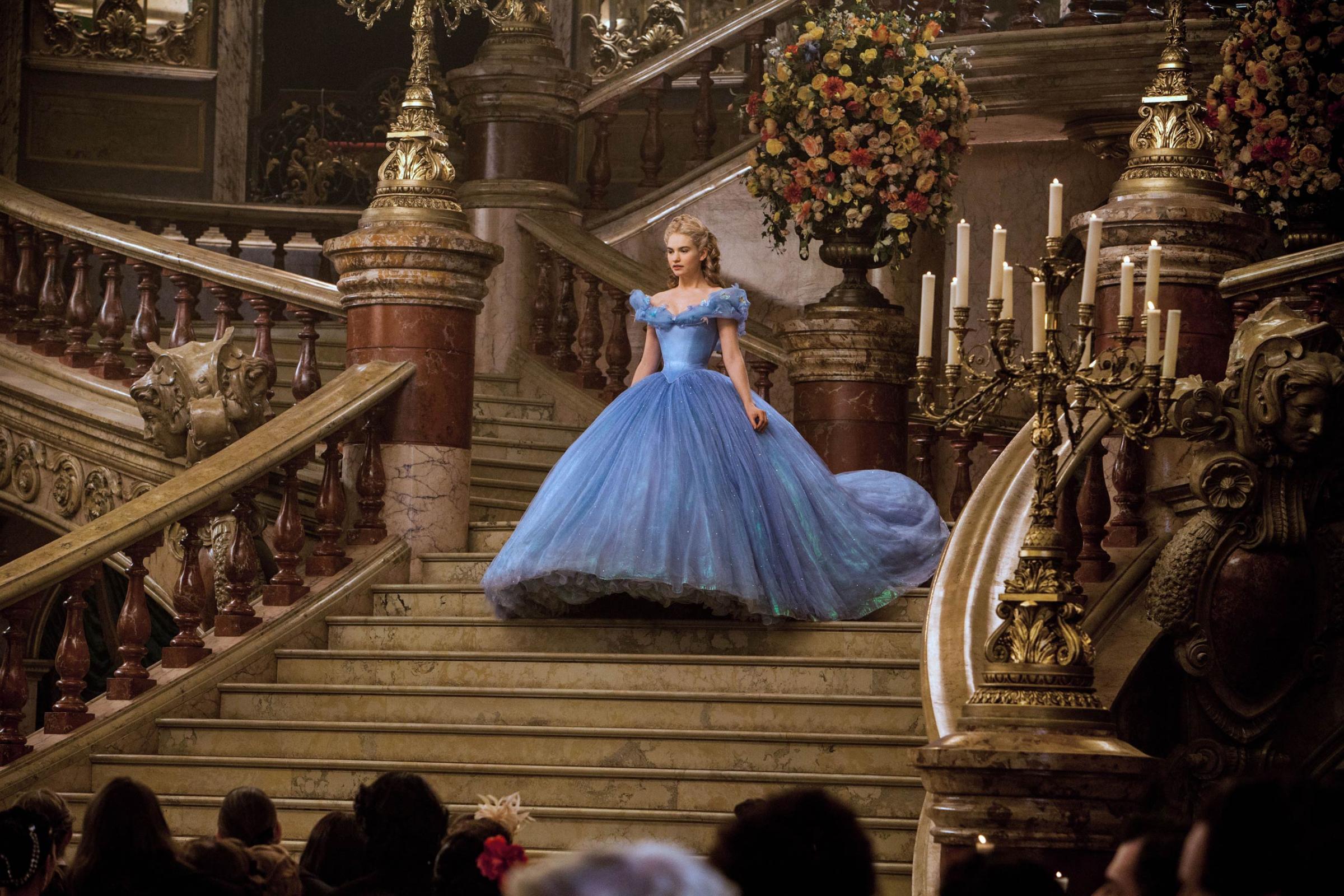

The latest version proves that third time’s the charm, with a Cinderella that is not revisionist but plain old visionist. In the recent Disney tradition of live-action film spun off from classic cartoon features — after Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland in 2010 and, last year, the Angelina Jolie Maleficent, from Sleeping Beauty — this Cinderella plays it straight and pretty. Make that gorgeous: the settings by Dante Ferretti and the gowns by Sandy Powell (each with three Oscar wins) turn the film into a fantasy land that is its own theme park. Even the attic to which James’s Ella is consigned by Blanchett’s Lady T. is less a Tower of Terror than an airy aerie.

First, though, the movie has to kill off Ella’s loving parents, with the ruthless efficiency that Disney perfected in such early features as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Bambi. Ella’s mother (Hayley Atwell) succumbs to the sort of genteel movie disease that deprives her of life but not of luster, instructing the child to “Have courage and be kind.” Father (Ben Chaplin), hoping to give Ella another mother and two new sisters her own age, marries the widow Tremaine, then dies while on a business trip. In short order, we see that Tremaine is no lady; she spits out her stepdaughter’s name as a cruel, cackling curse.

Tremaine has demoted Ella to charwoman in the service of the Lady’s sullen, stupid daughters Anastasia (Holiday Grainger) and Drizella (Sophie McShera). When the King (Derek Jacobi) invites every maiden to a ball at which the Prince (Richard Madden, who played Robb Stark on Game of Thrones) will choose his bride, Ella is left at home, finding transportation as well as transformation courtesy of her fairy godmother (Helena Bonham Carter). Ella leaves a glass slipper fit for a princess bride. Prince meets commoner, and the rest is fantasy.

Less a remake of the 1950 movie than a sensible correction, the Branagh Cinderella does without the old hit tunes or new any ones. Though it often seems ready to burst into song, it doesn’t, instead relying on Patrick Doyle’s sumptuous, nonstop score. It also reduces the mice, now CGI critters, to minor characters; Cinderella chats with them but they don’t talk back, content to await their roles as pumpkin-coach horses when the fairy godmother, in Bonham Carter’s mildly campy approximation, materializes. The movie’s only nod to modernity is in the casting of Afro-Brit Nonso Anozie (Xaro Xhoan Daxos on Game of Thrones) as the Prince’s stalwart Captain of the Guards.

Like Jolie in Maleficent, Blanchett gets top billing here. She earns it by radiating a hauteur that chills as it amuses; the performance is grand without skirting parody. The movie doesn’t rehabilitate Lady T., as Maleficent did for its sorceress. (In Disney’s 1950s Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty, both the Stepmother and Maleficent were voiced by Eleanor Audley.) But it does allow its star to sizzle as Cate the Blanch-ificent.

Blanchett’s Tremaine is the prisoner of her personality, parrying Cinderella’s aghast “How could you?” with a vitriolic and poignant “How could I not?” Behind her sadism is the sad awareness that her stepchild has all the graces her daughters lack. Her only blessing is that she finds an ally in the venal Grand Duke (Stellan Skarsgård), as adept as palace intrigue as Lady T. is at domestic iniquity. Perhaps these meanies should star in a sour sequel: Sinned- or Chagrined-erella.

The wicked stepmother gets a suitable antagonist in James, who plays Lady Rose on Downton Abbey as a figure of whim and rebellion: flirting with a black jazzman, marrying a Jewish lord. Her blond hair framing subversive dark eyebrows, James creates a Cinderella that is both classic and modern, the sculptor of her destiny.

This Cinderella needn’t wait for the royal ball to dazzle the Prince; she meets him earlier — as an equal, on horseback in the forest, with neither knowing the other’s identity — and persuades him to spare a stag he was hunting. He knows instantly he must marry the girl, who has been true to her mother’s last words: she is courageous and kind.

As expansive and well-scrubbed as any of the floors the heroine is obliged to scour, this PG-rated treat rekindles the old Disney magic in a ballroom dance of two strangers becoming lovers. It mixes romance and a measure of droll wit without ever evoking the dread phrase “rom-c0m.” Doing it the old way has paid off for the studio. Nearly a century after that black-and-white cartoon short, and 65 years after a “classic” animated feature that missed the mark, Disney finally got Cinderella right — for now and, happily, ever after.

See Cinderella Through the Years

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com