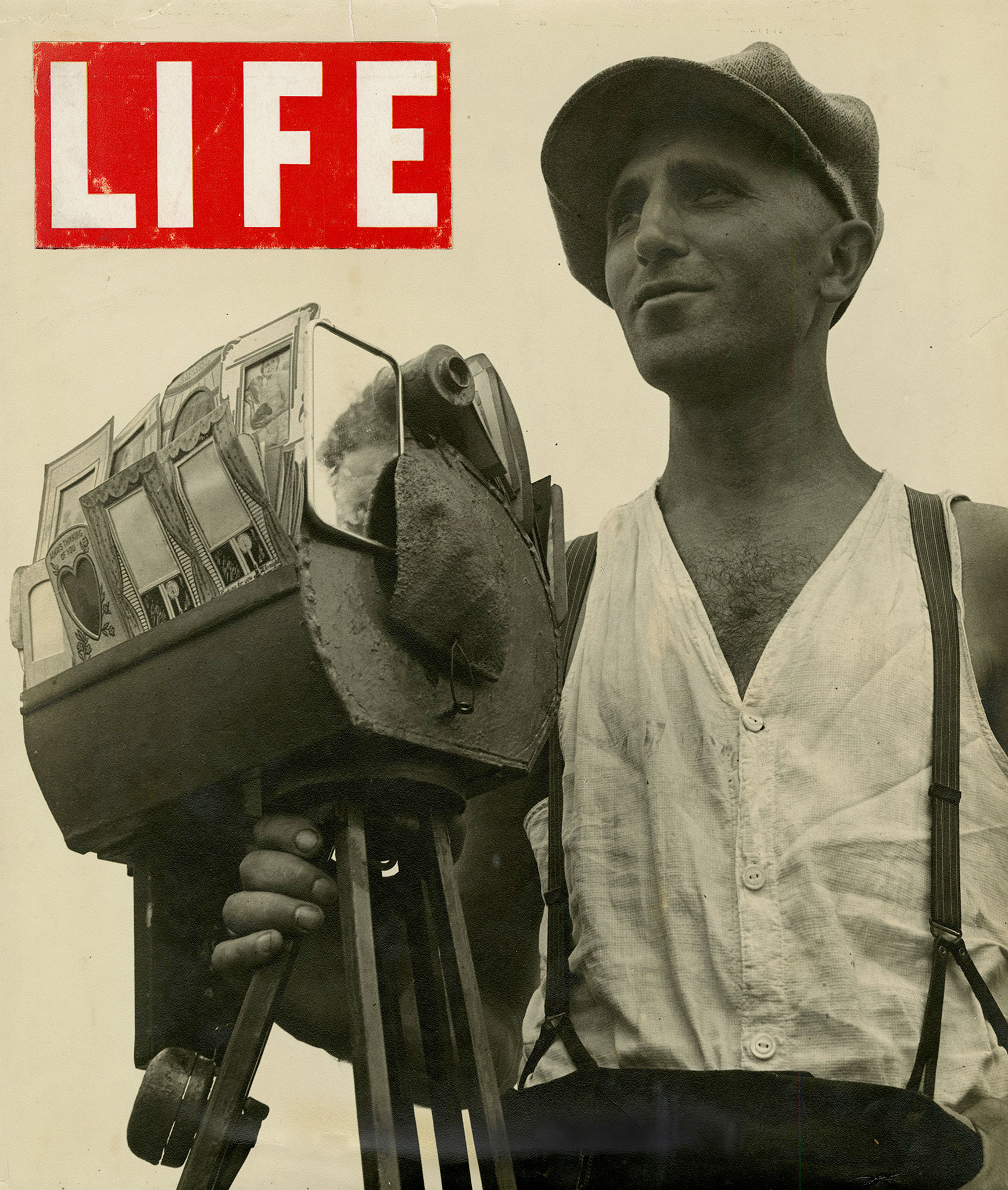

War correspondent, art collector, color consultant, creative director, world traveler — there were very few things Eliot Elisofon didn’t do during his long tenure as a staff photographer for LIFE Magazine. But as diverse as his talents were, they can all be traced to the first two jobs he ever held: artist and social worker.

Elisofon, whose work is featured in an exhibit at New York City’s Gitterman Gallery through April 18, would come to be known as one of the first photographers to extensively document Africa in photographs. But he made a compelling body of work on more familiar territory long before making his way onto LIFE’s payroll. Born in New York’s Lower East Side in 1911, Elisofon received a degree in social science from Fordham University in 1933. While studying and after graduation, he took a job as a social worker for the New York State Labor Department, snapping photos in his spare time.

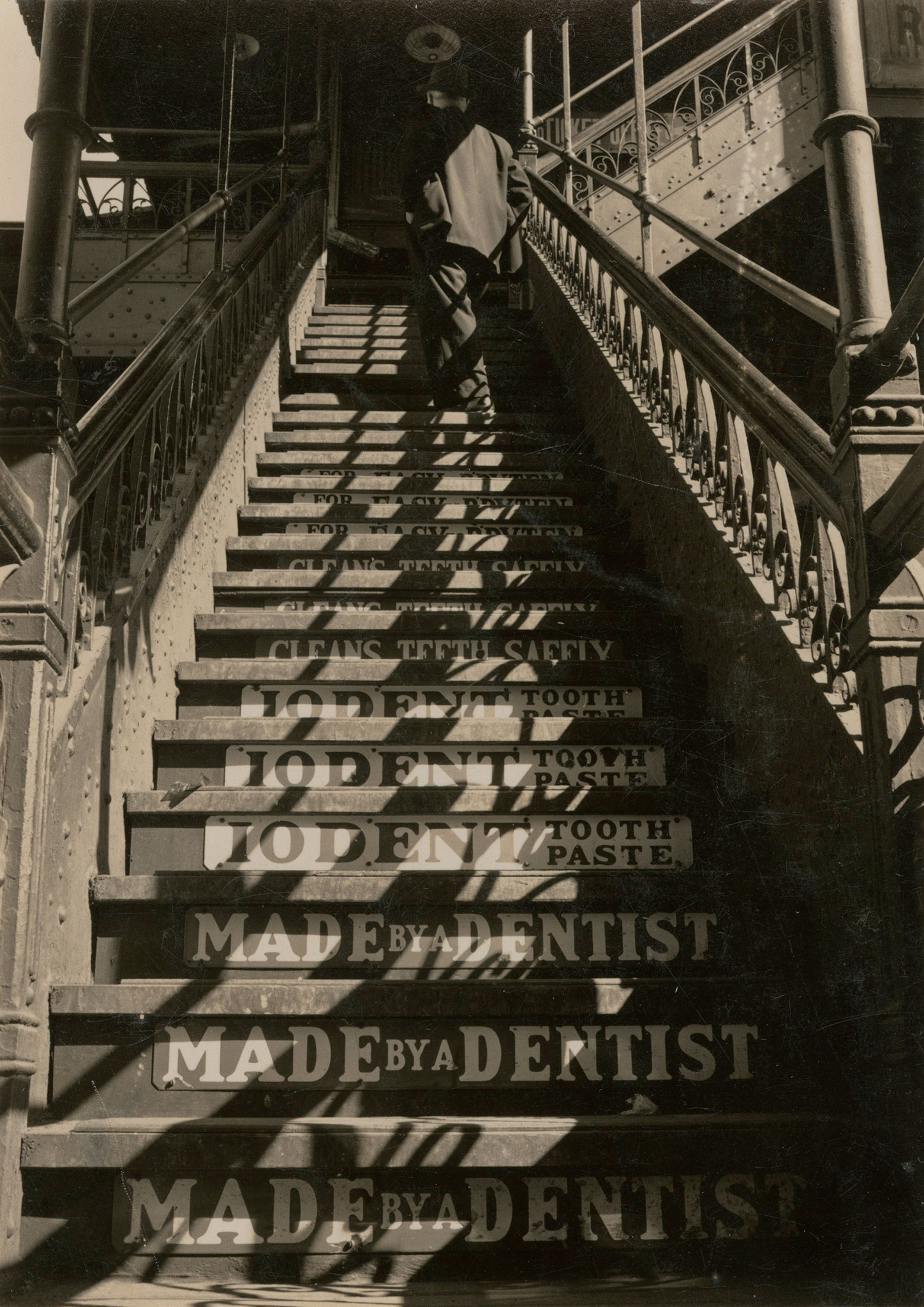

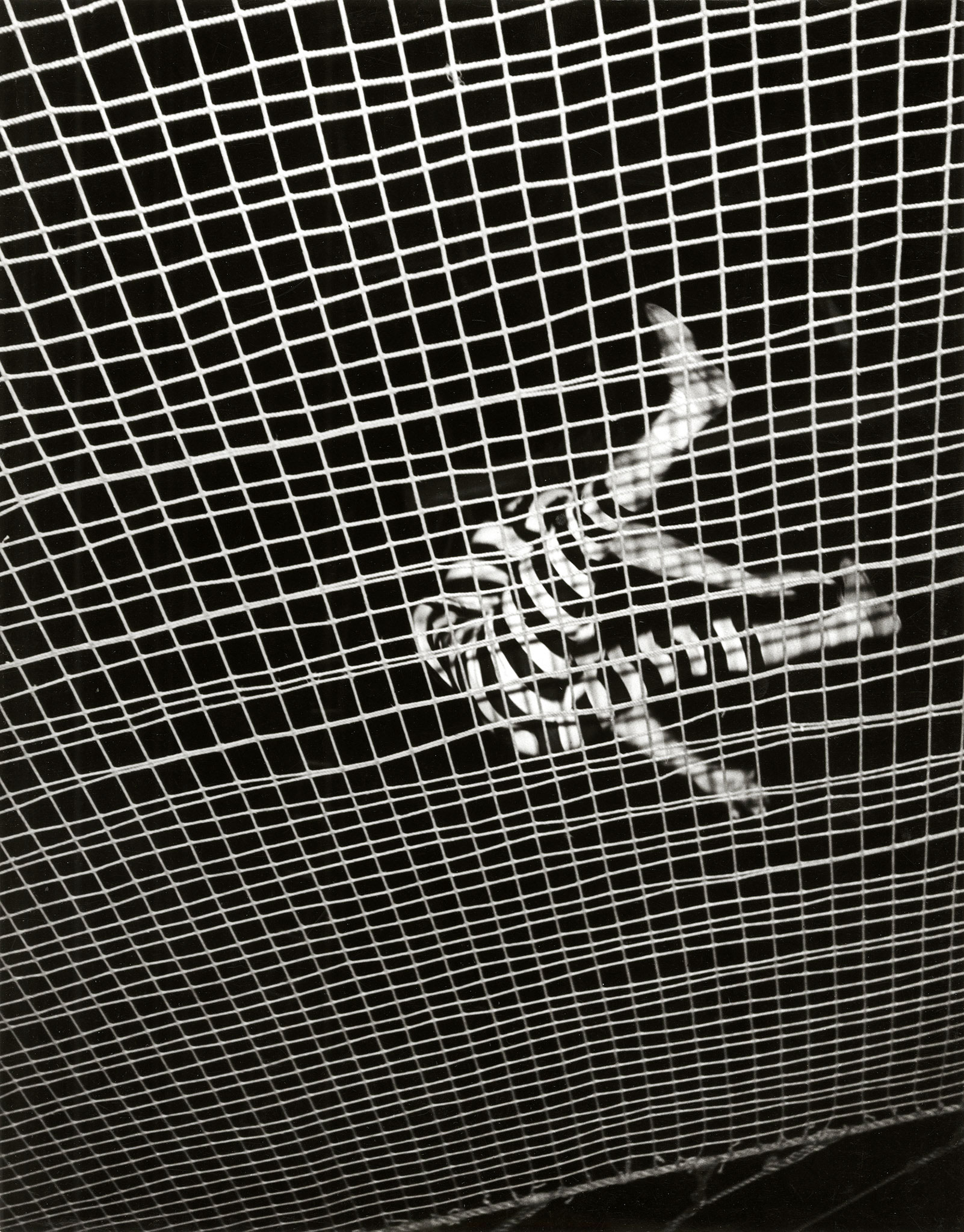

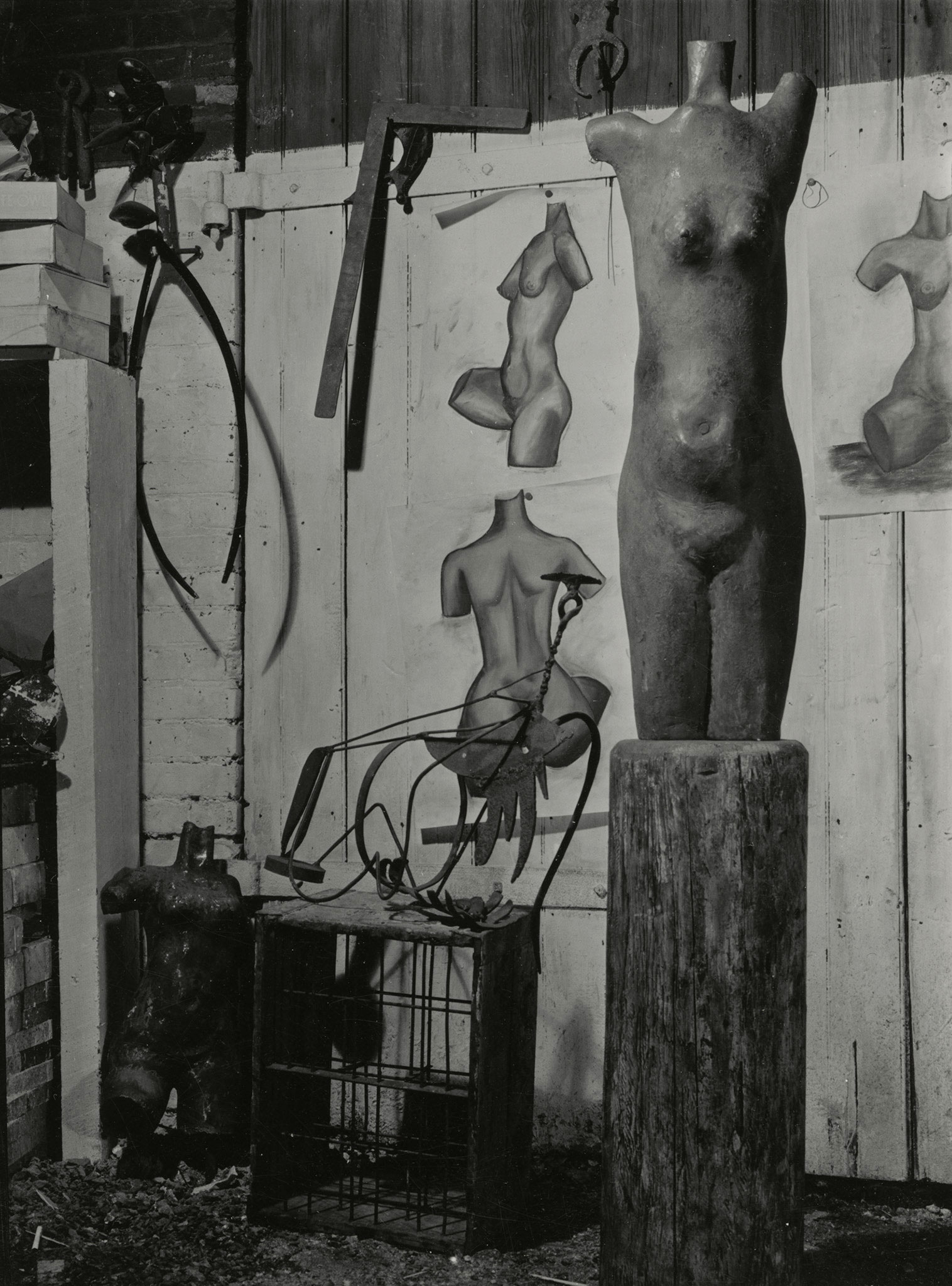

An admirer of Margaret Bourke-White and Picasso, Elisofon nursed a soft spot for painting that grew into a full-fledged portfolio of watercolors exhibited at museums and galleries around the world. As sensitive to light, texture and composition as he was to urban decay and social injustice, Elisofon’s early work was a combination of modern art and photojournalism, a blend that evolved over his lengthy career and positioned him as a versatile shooter. He was as comfortable creating Hollywood glamor shots as he was making candid portraits of African tribal leaders.

Like many young photographers, Elisofon’s first paying jobs were in advertising. While he would later revisit the techniques he learned from commercial photography, Elisofon had a fierce sense of artistic integrity and a keen understanding of the challenges artists face in making meaningful work while still earning a living.

In a 1953 lecture hosted by the Jewish Theological Seminary of America on “The Ethics and Morals of Creative Expression,” Elisofon explored the moral responsibility of the artist:

Am I immoral if I compromise my career? I began as a photographer in a commercial studio who spent the weekends photographing slum conditions in New York City. Some of my first magazine assignments were negative social reports in the South. I discovered that although great interest was shown by a few people in these studies that I could not get these stories published. Photography, and especially photo-reportage, is a medium which requires an audience. It soon became apparent to me that my career was at a standstill and I became a photographer of wider scope doing a variety of stories from the stars of Hollywood to the Atlantic Coast of the United States in order to gain recognition. I also managed to obtain assignments which interested me and which I felt had real value.

If Elisofon felt he had compromised by photographing celebrities, you’d never know it to look at the photos, as he approached these shoots with the same care and attention that he gave his work in Africa and on city streets. Equal parts technical virtuoso and acute observer, he saw social issues with an artist’s eyes, and documented them as a concerned photojournalist. His ability to turn urban decay into abstract art in his early work was an indication of the kind of duality and balance he would maintain throughout his career. He believed in the power of photography to inspire change, but he never underestimated the value of a beautiful image.

Krystal Grow is an arts writer and photo editor based in New York City. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram @kgreyscale

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com