It’s been five decades since American astronaut Edward White pushed himself out of his Gemini 4 capsule, stepped into the void — if one can “step” into anything while traveling at 17,000 m.p.h. — and became the first American to walk in space. It is a pivotal, celebrated moment in NASA’s annals; the space-age equivalent of a ship captain sketching a small human hand with a pointing finger in the margin of his otherwise perfunctory daily log, indicating an especially notable occurrence.

This mattered, the drawing says. This will be remembered.

Of course, the men and women at NASA and other space agencies around the world haven’t exactly been resting on their laurels since that day. More than a few humans have walked on the moon; the Space Shuttle program has come and (lamentably) gone; intrepid souls have engaged in “untethered extra-vehicular activities” a hundred miles above the planet; we’ve landed a prodigiously sophisticated, El Camino-sized roving laboratory on Mars; and not that long ago, the middle-aged and still-frisky Voyager 1 probe left our solar system and entered that mysterious realm known as interstellar space.

[MORE: Read Jeff Kluger’s “Gravity Fact Check: What the Season’s Big Movie Gets Wrong.”]

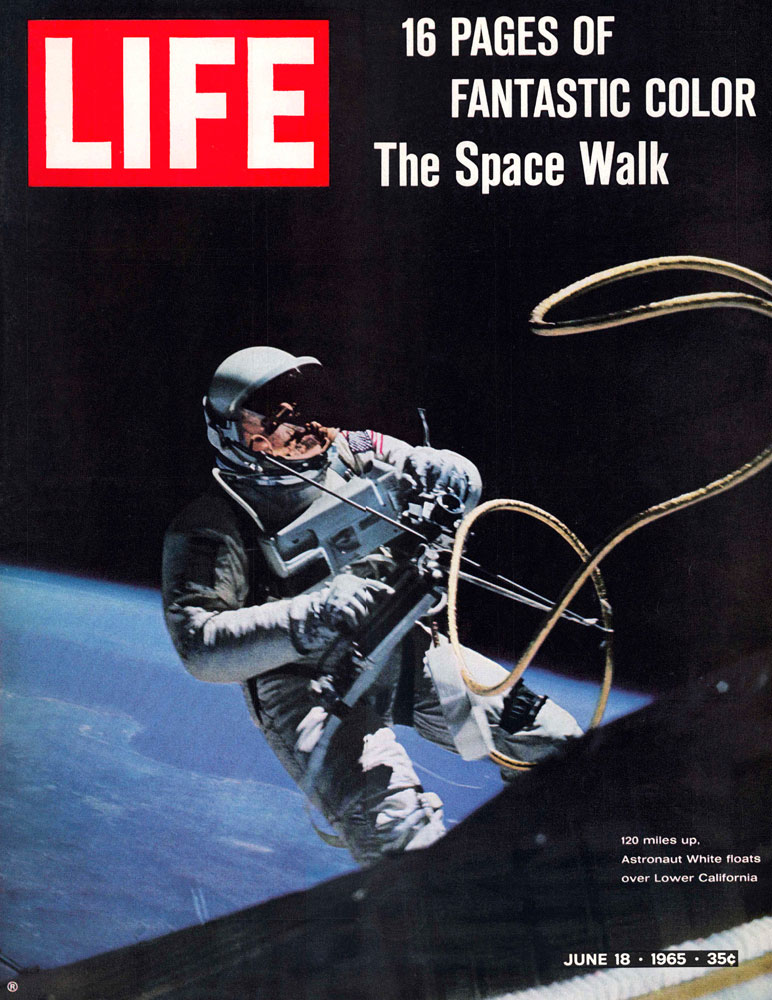

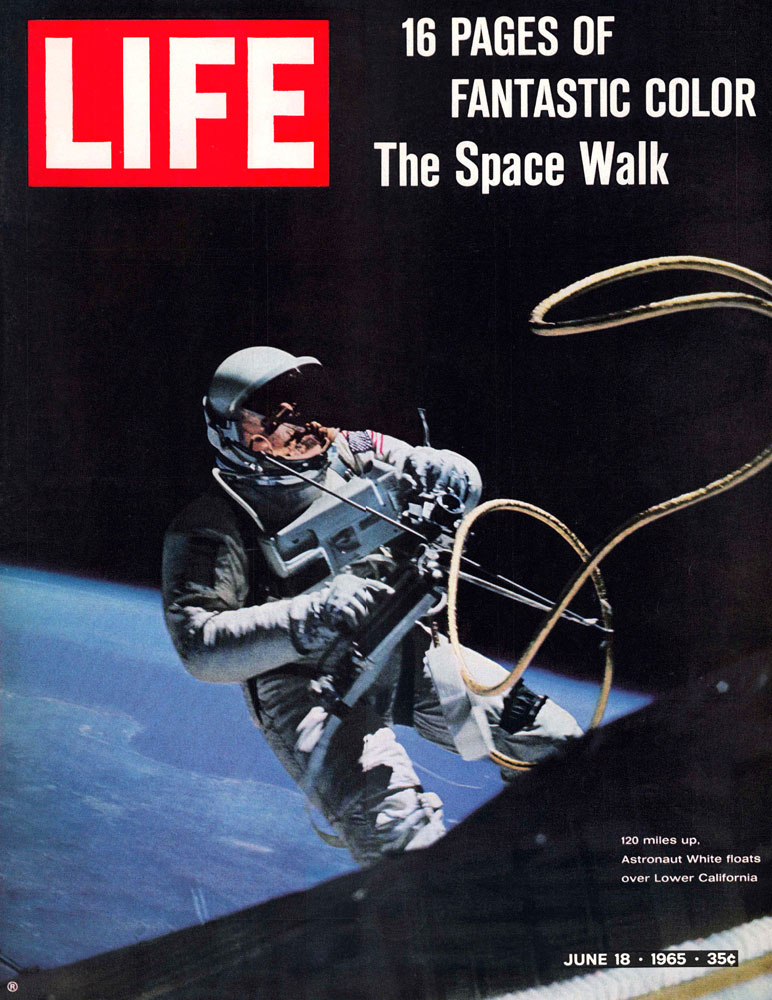

Still, all these years later, there’s something about White’s space walk — and, especially, about the wonderful color photographs of the endeavor made by Gemini 4 commander James McDivitt — that stirs heady emotions in the viewer.

There is a kind of riveting unease in the acknowledgment that the white-suited figure in the photos willingly left the relative safety of a cramped, 4-ton sardine can in order to float in space — a speck in the cosmos — and that no amount of testing can truly prepare anyone, or any mission, for that sort of landmark maneuver.

There is awe at the unparalleled beauty of the blue Earth so far below, weaving its ancient, elliptical course through the heavens.

Finally, there is at least a small measure of pride, warranted or not, in the realization that a mortal man, one of us, had the guts, the smarts and faith enough in himself and in his colleagues to do what Edward White did. (Note: Soviet cosmonaut Alexey Leonov was the very first person to walk in space, just three months before White’s walk, in March 1965.)

White and McDivitt’s adventure, meanwhile, remains notable not merely because it was a technical and imaginative touchstone of the Space Race, but because it produced some of the most memorable quotations from any NASA mission. And in light of the laconic charm that seems a key characteristic of so many astronauts, that’s saying something.

For instance, the jaunty, buddy-movie banter between White and McDivitt eventually wound down to one profoundly moving utterance, as White lets down his guard at the end and acknowledges the magnitude — the sheer, irreducible thrill — of what he has done:

McDIVITT: They want you to get back in now.

WHITE (laughing): I’m not coming in . . . This is fun.

McDIVITT: Come on.

WHITE: Hate to come back to you, but I’m coming.

McDIVITT: OK, come in then.

WHITE: Aren’t you going to hold my hand?

McDIVITT: Ed, come on in here … Come on. Let’s get back in here before it gets dark.

WHITE: I’m coming back in . . . and it’s the saddest moment of my life.

In that instant, with those words, we understand that White’s space walk was both an ennobling and profoundly humbling experience. He did not want it to end.

And who could blame him? What else, after all, could possibly compare?

Married and the father of two children, Lt. Col. Edward White was killed, along with fellow astronauts Gus Grissom and Roger Chaffee, when a fire broke out in their command module on Jan. 27, 1967, during a test countdown for their planned Apollo 1 mission. All three men were posthumously awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Honor — the highest award NASA bestows on its heroes.

— Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

t

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com