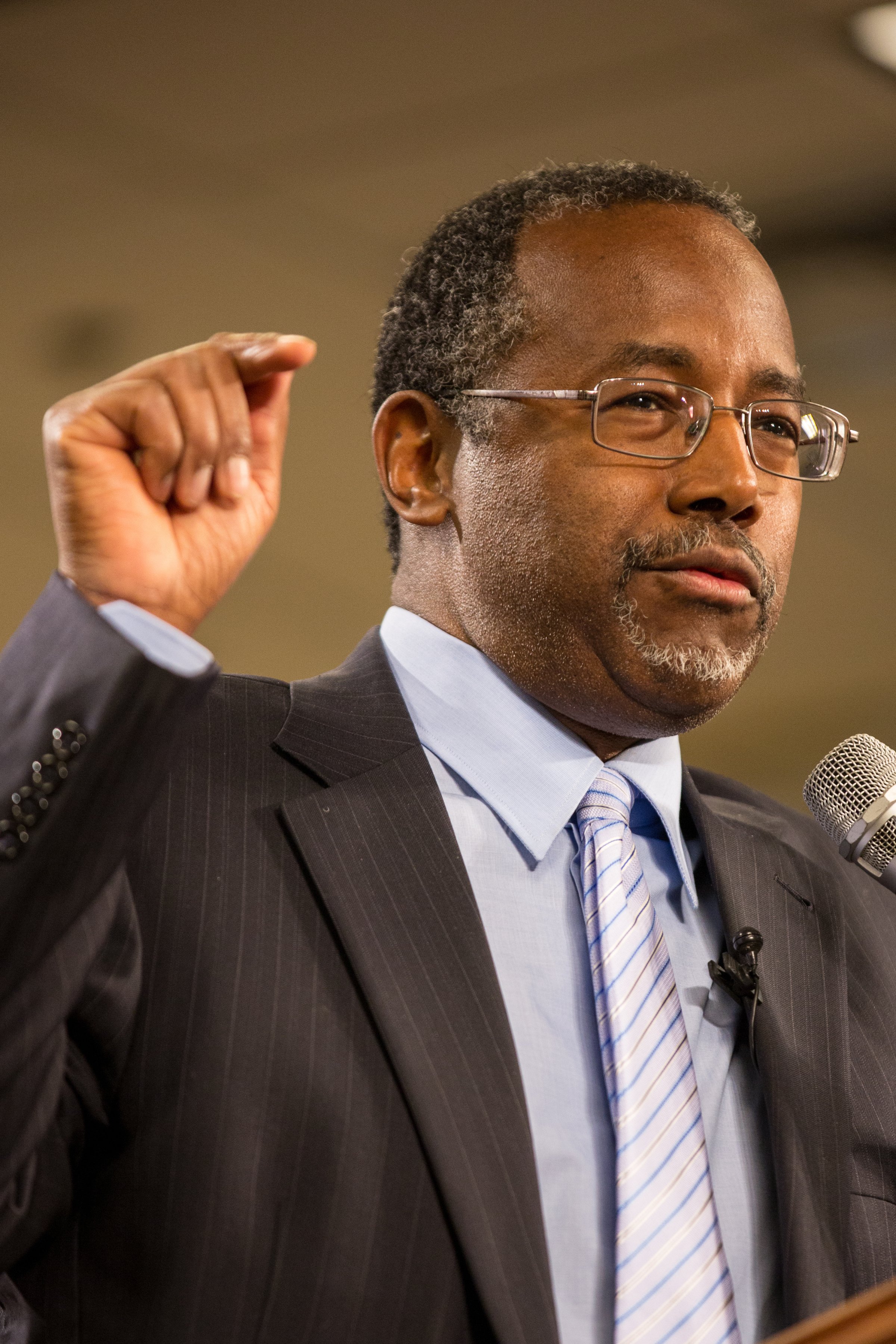

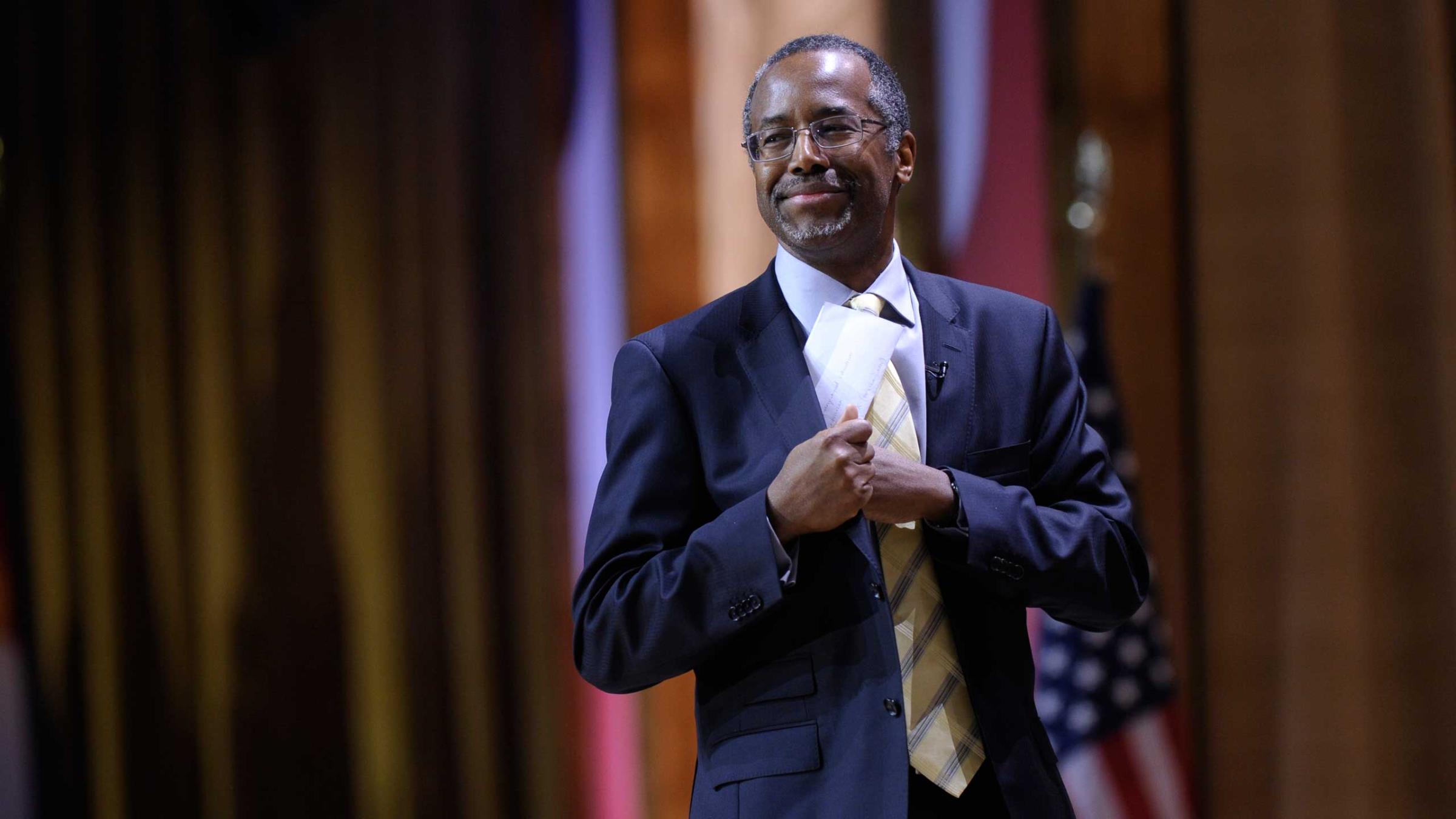

If you’re a candidate dreaming of the White House with virtually no chance of actually winding up there, it sometimes helps to say something ridiculous—if only to get your name-recognition numbers up. That is the very best and most charitable explanation for comments by Dr. Ben Carson, a neurosurgeon, on CNN, arguing that homosexuality is “absolutely” a choice. His evidence? Prison.

“A lot of people who go into prison go into prison straight and when they come out, they’re gay,” he said. “So did something happen while they were in there?”

Prison, of course, is the worst of all possible examples Carson could have chosen—conflating sexuality with circumstance. Men confined together for years without women remain sexual beings and may take whatever outlet is available to them. Something similar was true in a less enlightened era of gay men and women who were forced to marry people of the opposite sex, and who dutifully produced children and tried to satisfy their partners despite the fact that they were getting little satisfaction themselves.

Carson, who was blowtorched in both social and mainstream media for his remarks, quickly walked them back, issuing a statement that, in some ways, only made things worse. “I’m a doctor trained in multiple fields of medicine, who was blessed to work at perhaps the finest institution of medical knowledge in the world,” he wrote. “Some of our brightest minds have looked at this debate, and up until this point there have been no definitive studies that people are born into a specific sexuality.”

That statement could indeed have the virtue of being true—provided it was issued in 1990. But since then, there’s been a steady accumulation of evidence that sexuality—like eye color, nose size, blood type and more—is baked in long before birth. The first great breakthrough was the 1991 study by neuroscientist Simon LeVay finding that a region in the hypothalamus related to sexuality known as INAH3 is smaller in gay men and women than it is in straight men. The following year, investigators at UCLA found that another brain region associated with sexuality, the midsagittal plane of the anterior commissure, is 18% larger in gay men than in straight women and 34% larger than in straight men.

One cause of the differences could be genetic. In 1993, one small study suggested a connection between sexual orientation and a section on the X chromosome called Xq28, which could predispose men toward homosexuality. The small size of the study—only 38 pairs of gay brothers—made it less than entirely reliable. But a study released just last year expanded the sample group to 409 pairs of brothers and reached similar conclusions.

Genes are not the only biological roots for homosexuality. Womb environment is thought to play a significant role too, since part of what determines development of a fetus is the level and mix of hormones to which it is exposed during gestation. In 2006, psychologist Anthony Bogaert of Brock University in Canada looked into the never-explained phenomenon of birth order appearing to shape sexuality, with gay males tending to have more older brothers than straight males. Working with a sample group of 944 homosexual and heterosexual males, Bogaert found that indeed, a first born male has about a 3% chance of being gay, a number that goes up 1% at a time for each subsequent boy until it doubles to 6% for a fourth son.

The explanation likely involves the mother’s immune system. Any baby, male or female, is initially treated as an invader by the mother’s body, but multiple mechanisms engage to prevent her system from rejecting the fetus. Male babies, with their male proteins, are perceived as slightly more alien than females, so the mother’s body produces more gender-specific antibodies against them. Over multiple pregnancies with male babies, the womb becomes more “feminized,” and that can shape sexuality.

A range of other physical differences among gay men and lesbians also argue against Carson’s thinking—finger length for instance. In heterosexual men, the index finger is significantly shorter than the ring finger. In straight women, the index and ring fingers are close to the same length. Lesbian finger length is often more similar to that of straight males. This, too, had been informally observed for a long time, but in 2000 a study at the University of California, Berkeley, seemed to validate it.

Lesbians also seem to have differences in the inner ear—of all unlikely places. In all people, sound not only enters the ear but leaves it, in the form of what are known as otoacoustic emissions—vibrations that are produced by the interaction of the cochlea and eardrum and can be detected by instruments. Heterosexual women tend to have higher frequency otoacoustic emissions than men, but gay women don’t. Still other studies have explored a link between homosexuality and handedness (with gays having a greater likelihood of being left-handed or ambidextrous) as well as hair whorl (with the hair at the crown of gay men’s heads tending to grow counterclockwise), though there are differing views on these last two.

Clearly, none of us choose our genetics or finger length or birth order or ear structure, and none of us choose our sexuality either. As with so many cases of politicians saying scientifically block-headed things, Carson either doesn’t know any of this (and as a doctor, he certainly should) or he does know it and is pretending he doesn’t. Neither answer reflects well on his fitness for political office.

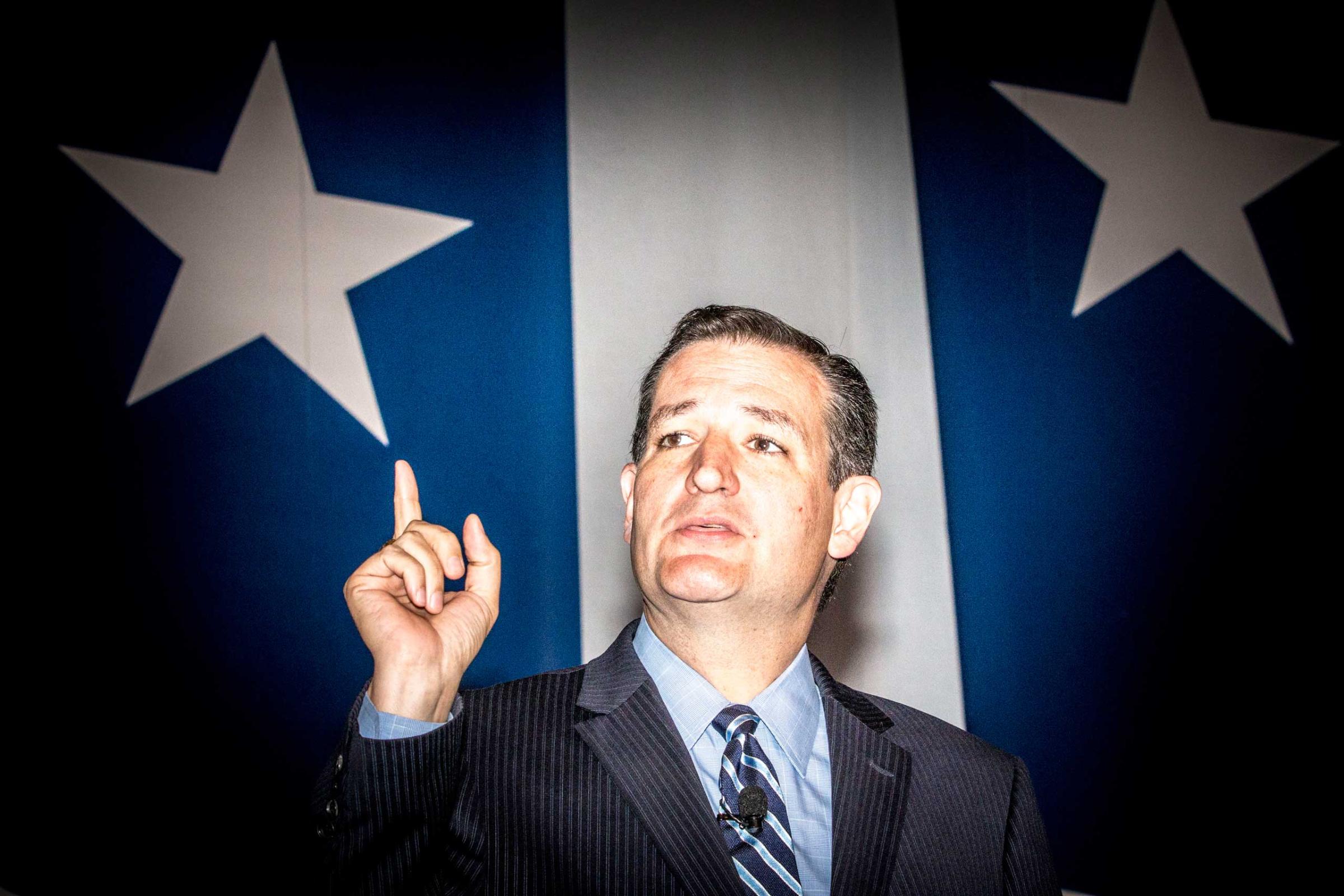

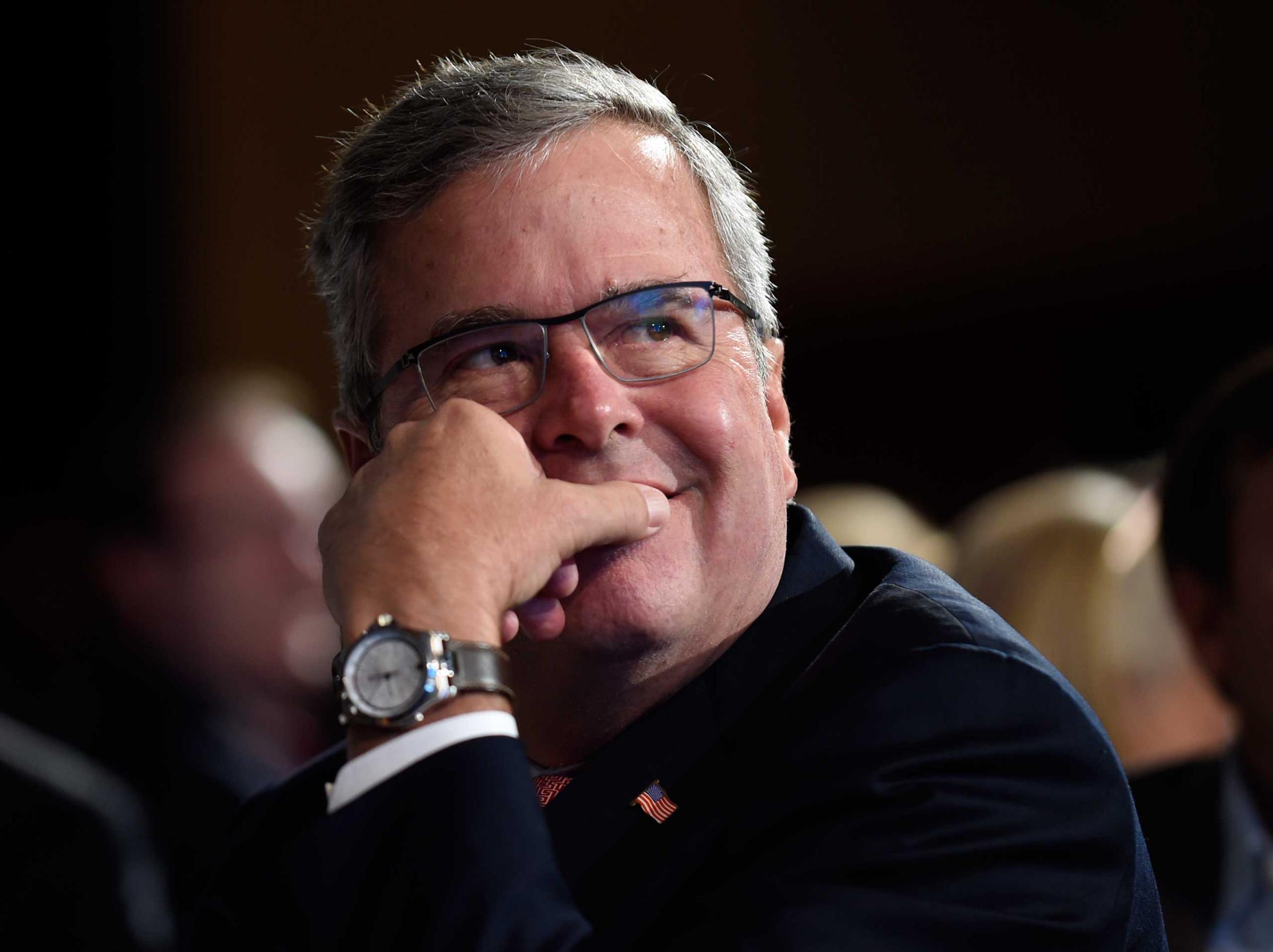

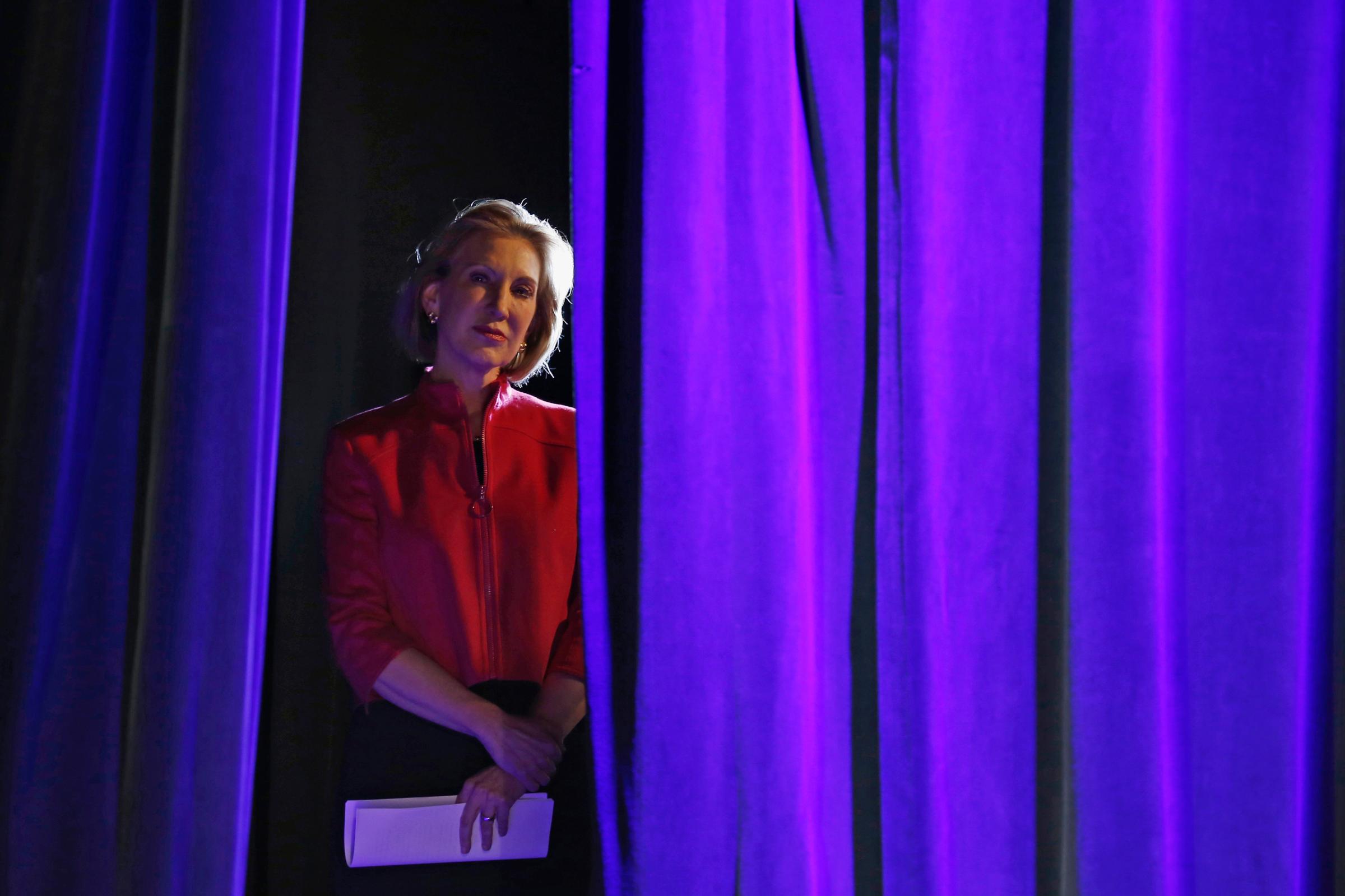

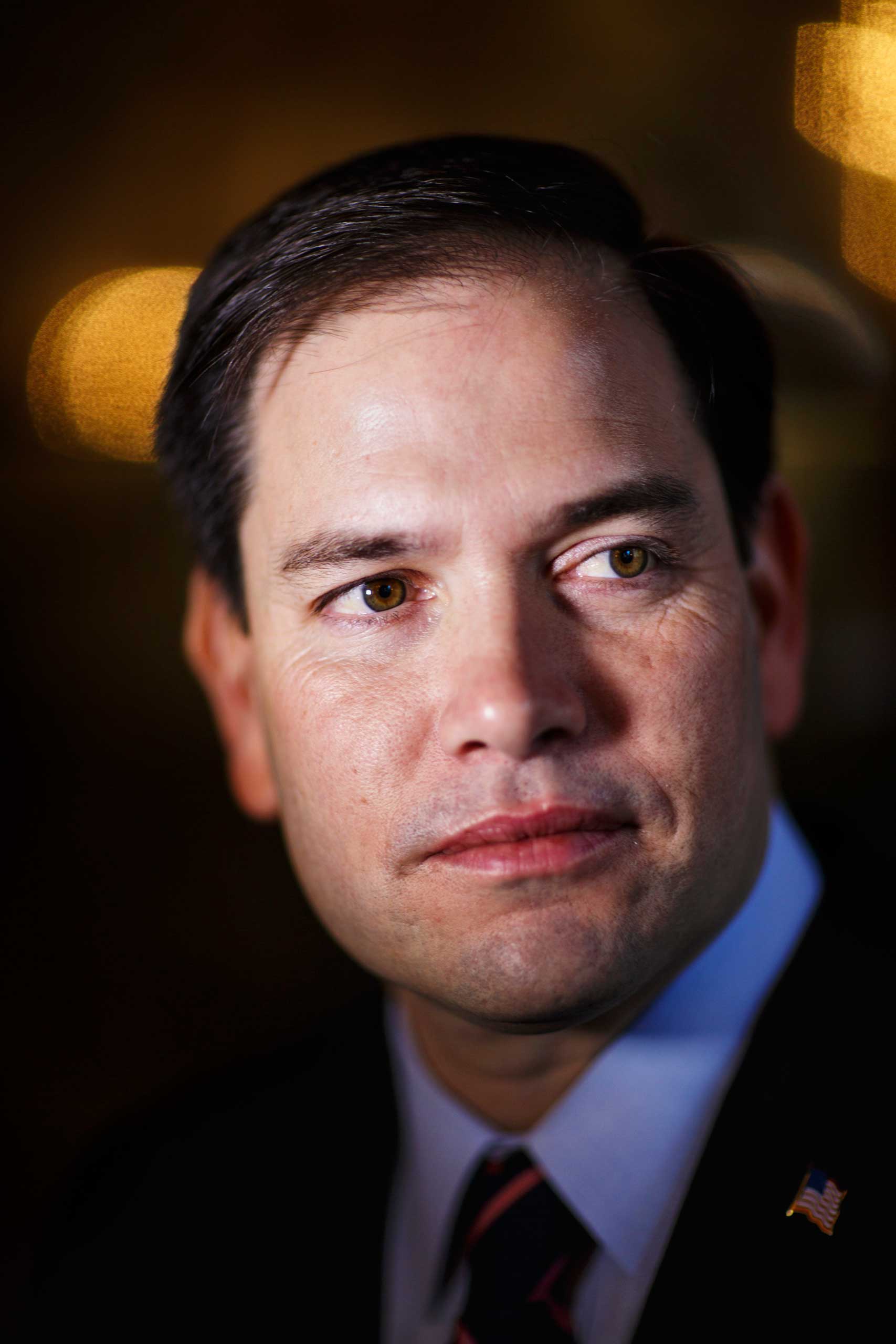

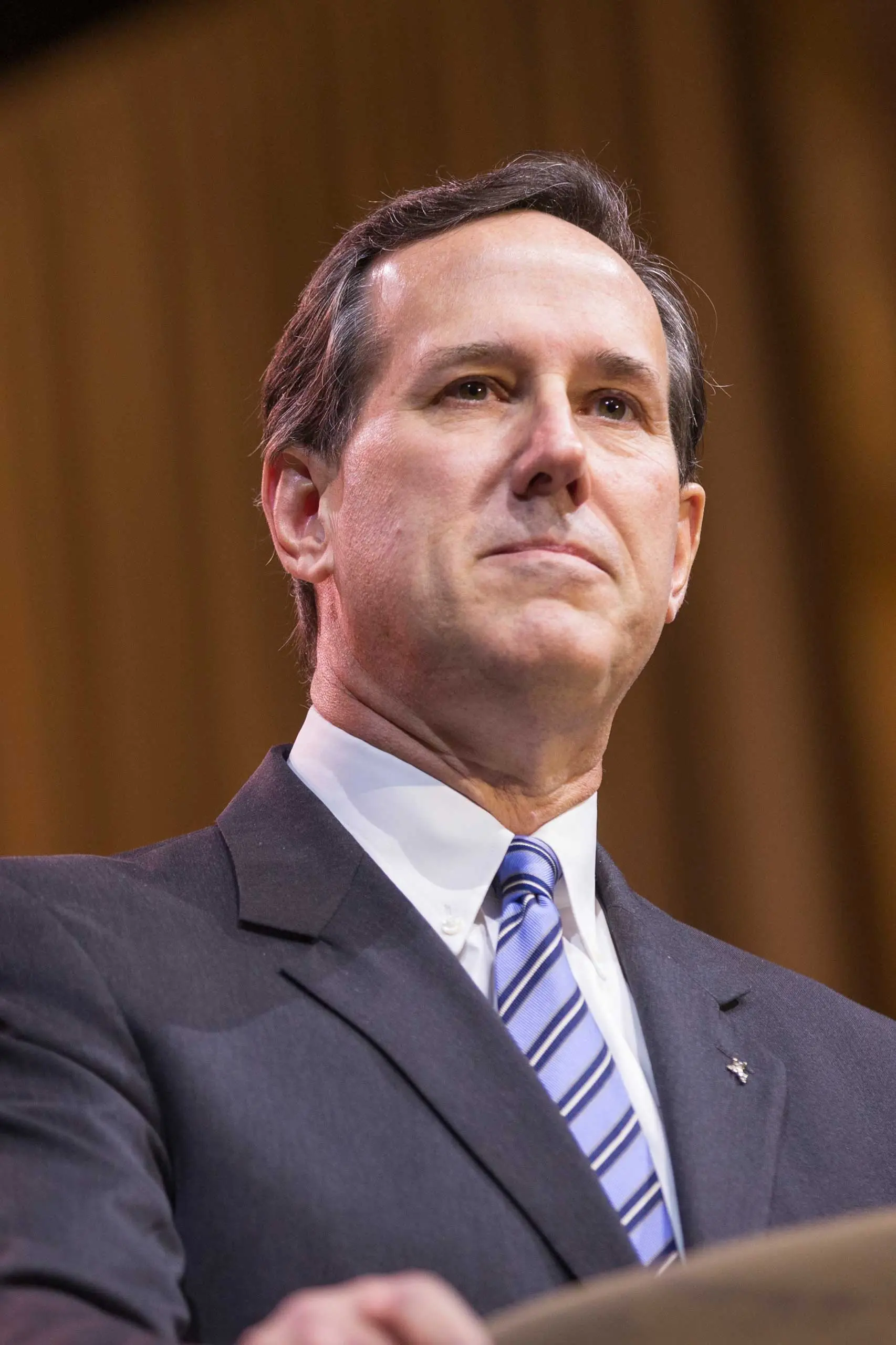

See the 2016 Candidates Looking Very Presidential

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com