It was late April of 1968 when Ronald Ridenhour “first heard of ‘Pinkville’ and what had allegedly happened there.”

Thus began the letter that he sent to several government officials, including President Richard Nixon, in March, 1969. What followed was an account of the March 16, 1968, massacre at My Lai. “Ridenhour did not witness the incident himself, but he kept hearing about it from friends who were there,” TIME, which misidentified him as “Richard,” recounted after the news became public. “He was at first disbelieving, then deeply disturbed.”

That letter would soon change the way American citizens thought and talked about the war in Vietnam. This is how Ridenhour described what had happened:

One village area was particularly troublesome and seemed to be infested with booby traps and enemy soldiers. It was located about six miles northeast of Quang Nh,ai city at approximate coordinates B.S. 728795. It was a notorious area and the men of Task Force Barker had a special name I for it: they called it “Pinkville.” One morning in the latter part of March, Task Force Barker moved out from its firebase headed for “Pinkville.” Its mission: destroy the trouble spot and all of its inhabitants.

When “Butch” told me this I didn’t quite believe that what he was telling me was true, but he assured me that it was and went on to describe what had happened. The other two companies that made up the task force cordoned off the village so that “Charlie” Company could move through to destroy the structures and kill the inhabitants. Any villagers who ran from Charlie Company were stopped by the encircling companies. I asked “Butch” several times if all the people were killed. He said that he thought they were men, women and children. He recalled seeing a small boy, about three or four years old, standing by the trail with a gunshot wound in one arm. The boy was clutching his wounded arm with his other hand, while blood trickled between his fingers. He was staring around himself in shock and disbelief at what he saw. “He just stood there with big eyes staring around like he didn’t understand; he didn’t believe what was happening. Then the captain’s RTO (radio operator) put a burst of 16 (M-16 rifle) fire into him.” It was so bad, Gruver said, that one of the men in his squad shot himself in the foot in order to be medivaced out of the area so that he would not have to participate in the slaughter. Although he had not seen it, Gruver had been told by people he considered trustworthy that one of the company’s officers, 2nd Lieutenant Kally (this spelling may be incorrect) had rounded up several groups of villagers (each group consisting of a minimum of 20 persons of both sexes and all ages). According to the story, Kally then machine-gunned each group. Gruver estimated that the population of the village had been 300 to 400 people and that very few, if any, escaped.

After hearing this account I couldn’t quite accept it. Somehow I just couldn’t believe that not only had so many young American men participated in such an act of barbarism, but that their officers had ordered it.

The full letter, which is widely available these days, ran to about 2,000 words worth of evidence that “something very black indeed” had happened. Further publicity came in the form of an investigation by reporter Seymour Hersh — which originally ran in a Washington news service after LIFE magazine rejected it.

More from TIME

In the fall of 1969, one of the leaders of the platoon implicated in the massacre — his name was actually spelled Calley — was charged with murdering civilians; other charges against other soldiers and officers followed. Comparisons to the Nuremberg Trials were many, especially as many of the soldiers there argued that they had just been following orders. There were several legal difficulties in pursuing a lawsuit against them, both logistical and sentimental, as TIME polls found that many Americans either did not believe Ridenhour’s account or thought that such killing was a natural result of war.

Several trials did move forward, however. In 1971, Calley was found guilty. (Other trials for those present continued, but Calley was the only one convicted.) The sentencing did not end My Lai’s reverberations. At a protest in New York, future Secretary of State John Kerry read this statement: “We are all of us in this country guilty for having allowed the war to go on. We only want this country to realize that it cannot try a Calley for something which generals and Presidents and our way of life encouraged him to do. And if you try him, then at the same time you must try all those generals and Presidents and soldiers who have part of the responsibility. You must in fact try this country.” The verdict split the U.S. between those who thought that punishments for the massacre should instead go all the way up to the Commander-in-Chief, and those who thought that condemning soldiers for killing was a travesty in its own right.

“The crisis of conscience caused by the Calley affair is a graver phenomenon than the horror following the assassination of President Kennedy,” TIME opined. “Historically, it is far more crucial.”

Though the nation was divided at the time, history has come out fairly firmly on one side: in 1998, three men who turned their weapons on fellow soldiers instead of My Lai residents were honored in Washington — shortly before Ridenhour died at 52 of a heart attack — and in 2009 Calley apologized for his role in what happened. “There is not a day that goes by,” he said, “that I do not feel remorse.”

Read TIME’s 1969 issue about the fallout from My Lai: The Massacre: Where Does the Guilt Lie?

See how LIFE reported on My Lai: American Atrocity

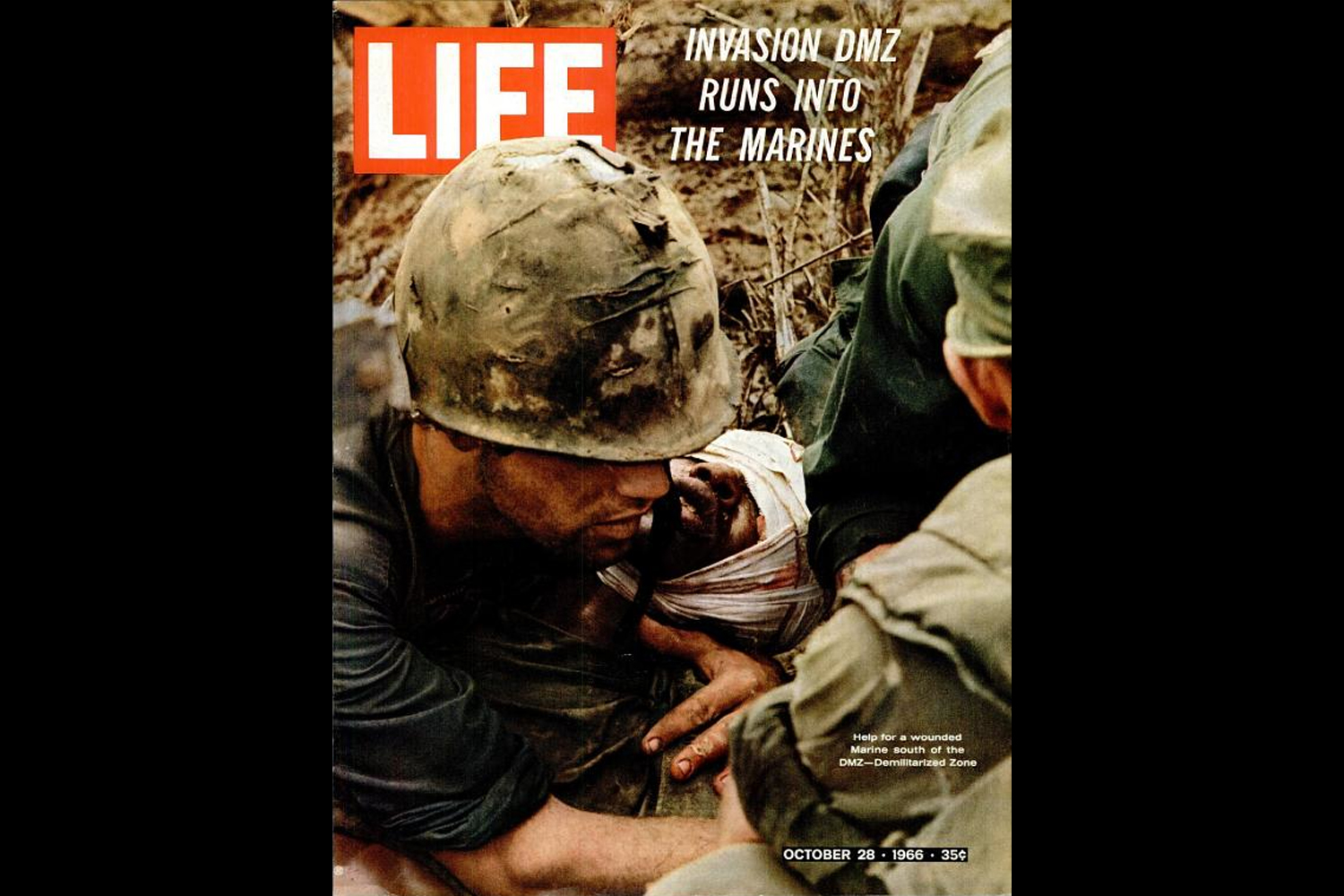

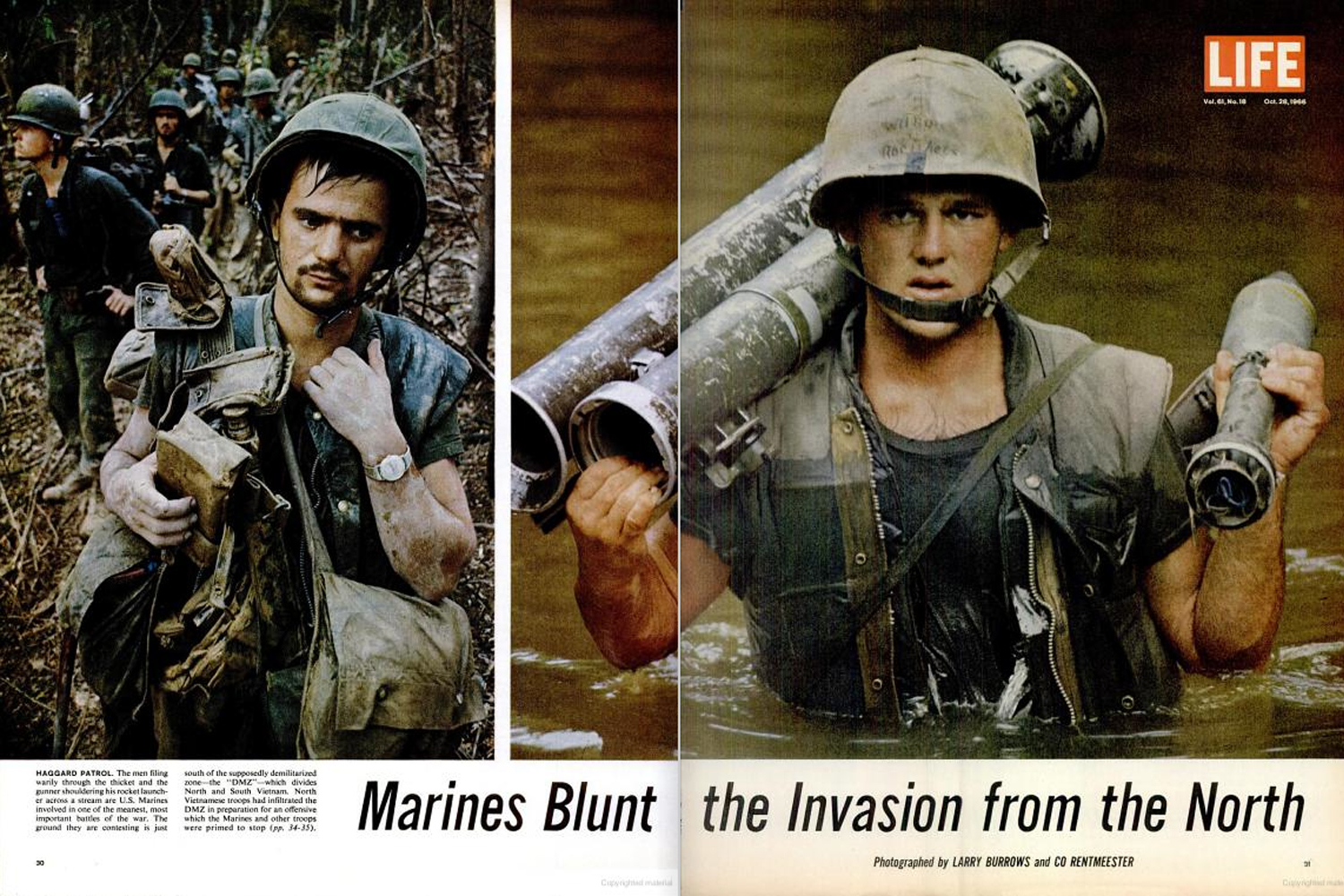

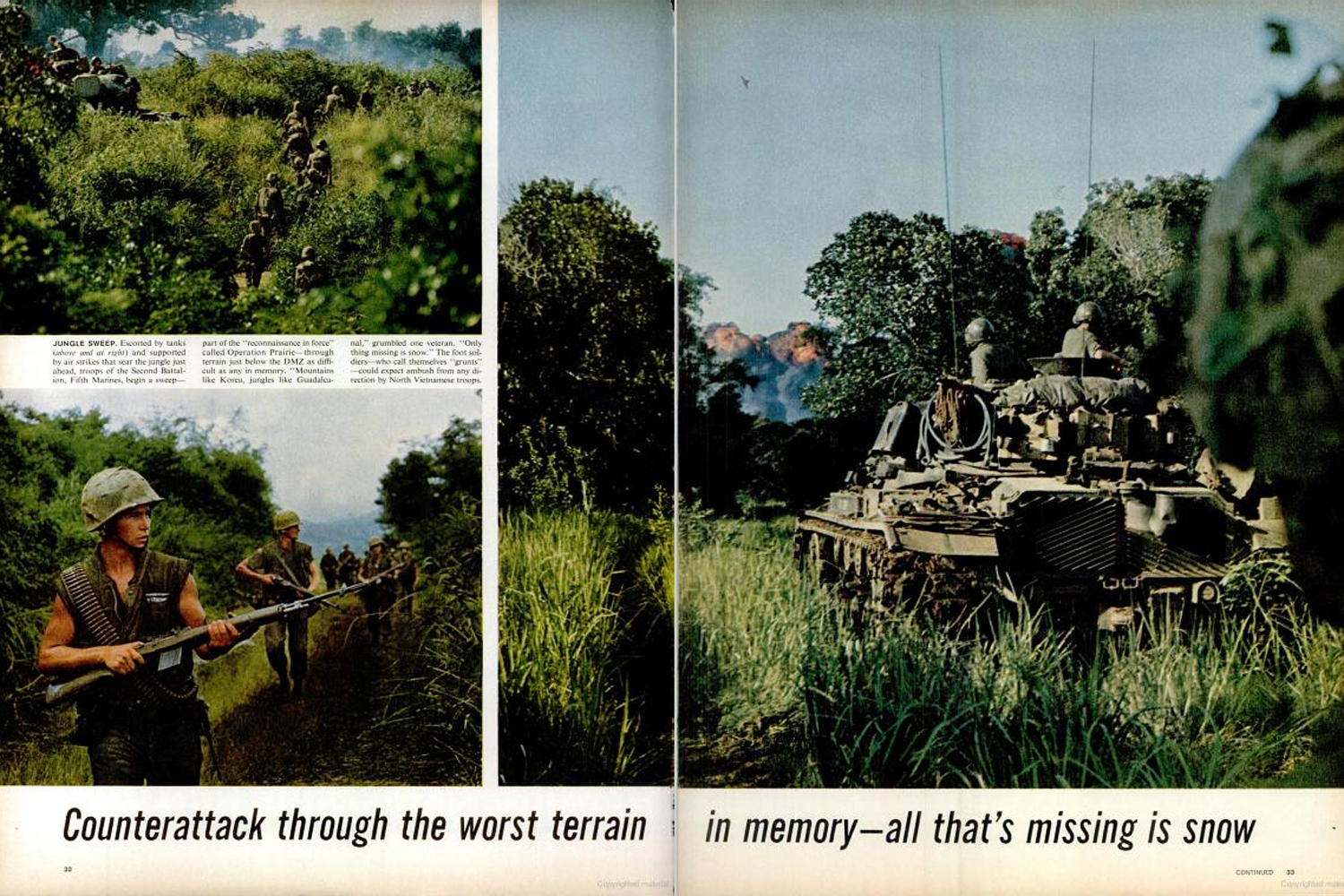

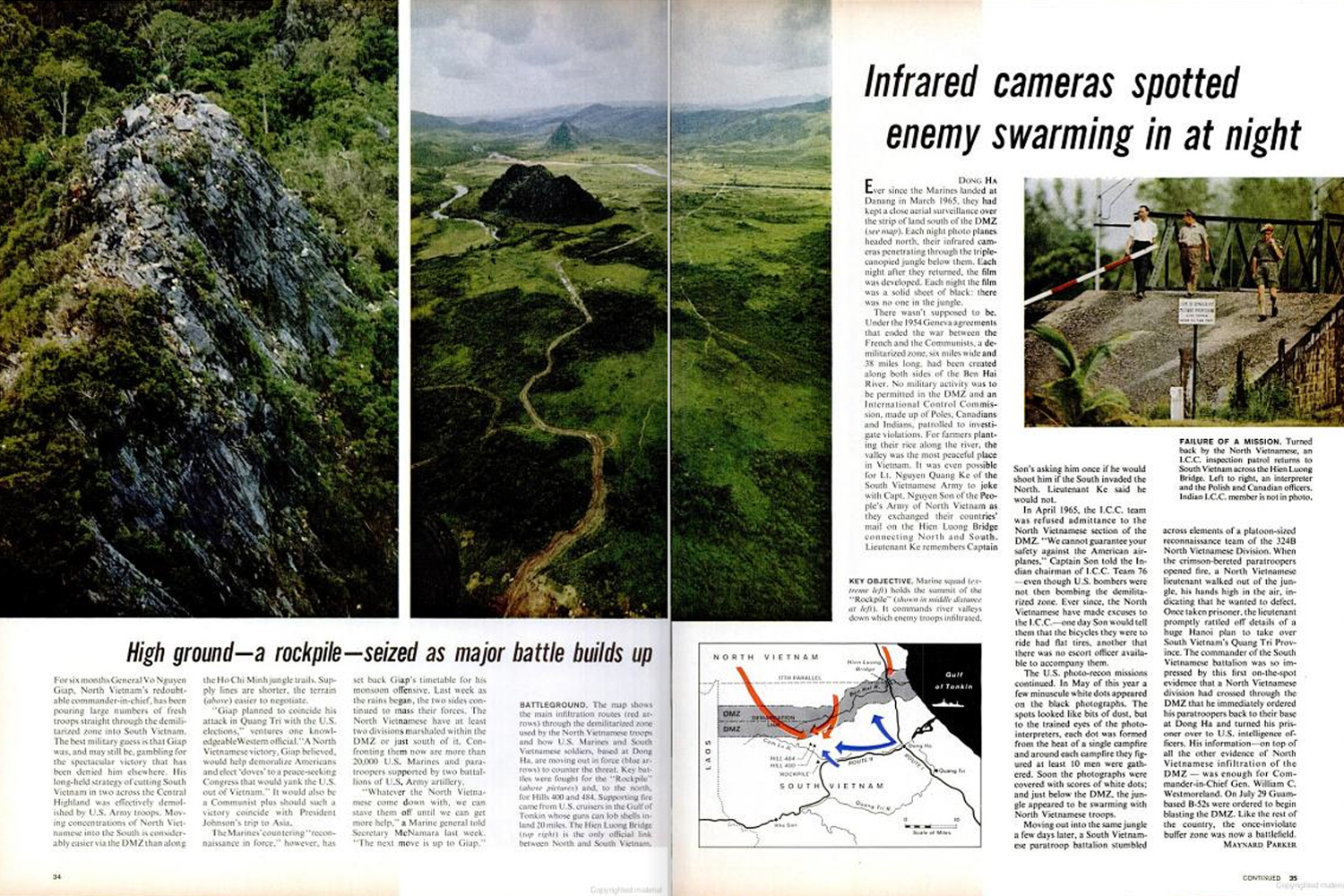

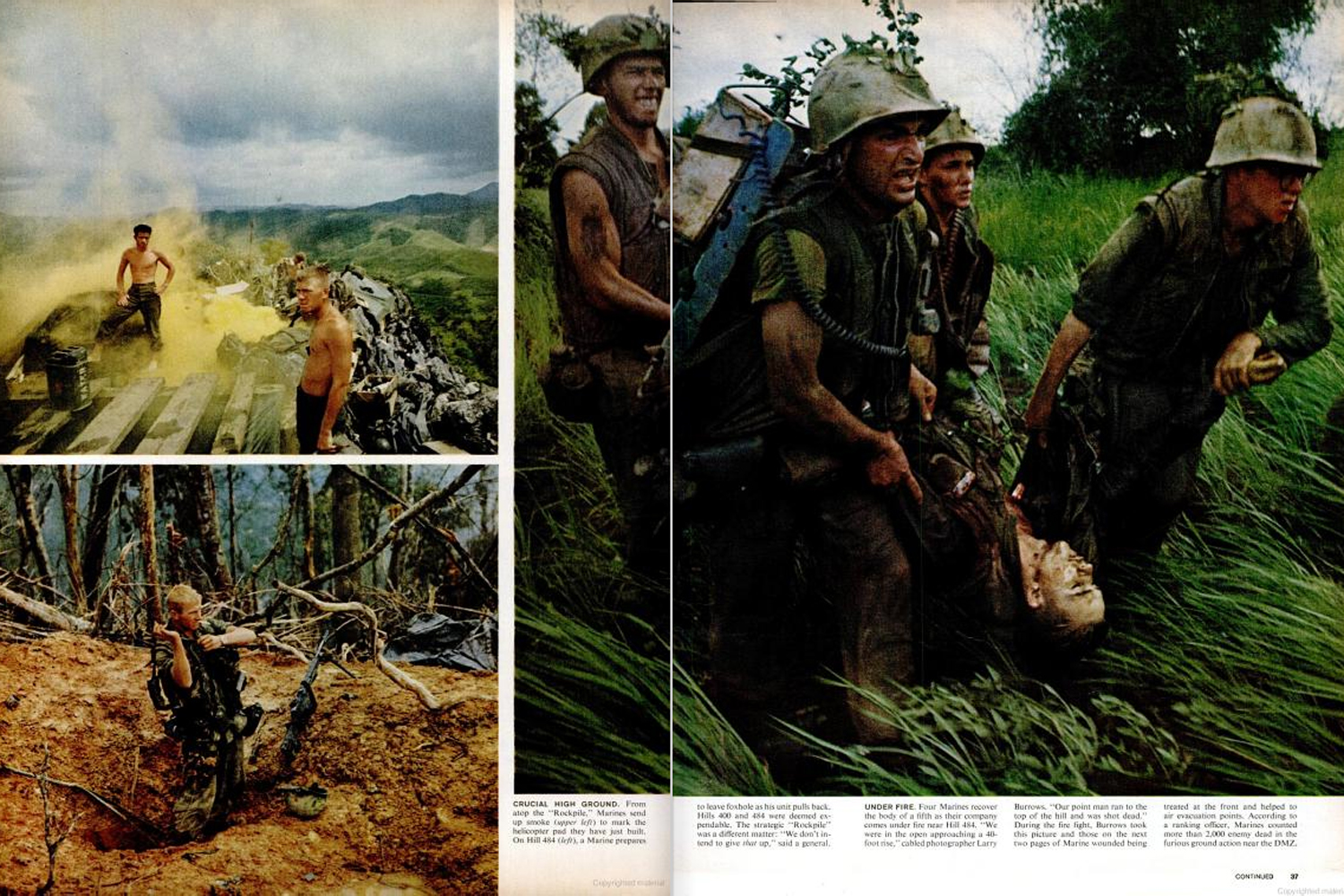

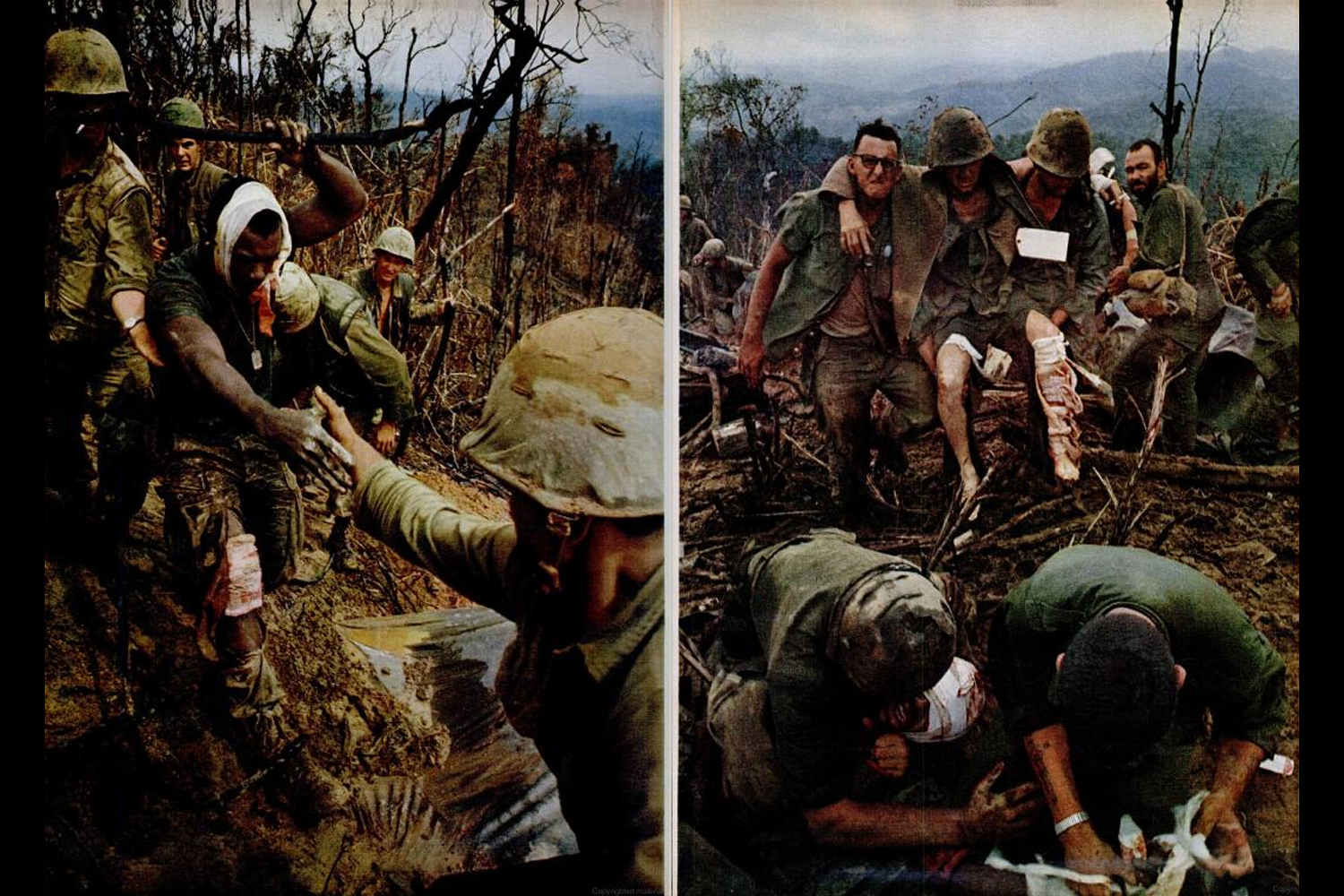

LIFE Behind the Picture: Larry Burrows' 'Reaching Out,' Vietnam, 1966

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com