When the Supreme Court last considered the Affordable Care Act, the argument was easy to follow: Does the federal government have the power to force people to buy health insurance?

The question this time is a lot more complicated.

As the justices discussed a single line in the law Wednesday, they were debating issues of administrative law precedent, congressional intent and interpretation of statutory language. But the bottom line is still the same. If the court’s majority rules a certain way, the law would collapse, causing as many as eight million people to lose their health insurance.

The case centers on whether states need to set up their own health insurance exchanges under the law for their residents to qualify for subsidies that make it affordable.

Here’s a quick look at four ways the court could rule.

The Liberal Hail Mary

The ruling: The majority finds that the people bringing the lawsuit don’t have the standing to sue and throws out the case without ruling on the merits.

The argument: One plaintiff listed her address as a motel. The others might qualify for veterans health care or Medicare, which would make their claims of being hurt by the law a moot point.

Why they would do it: Chief Justice John Roberts might agree with the liberal justices as a face-saving way to make the case go away. He was quiet during oral arguments Wednesday.

Why they wouldn’t do it: Even if three of the four plaintiffs don’t have standing, if the fourth did, the case could move forward. It’s a longshot.

The Ironic Precedent

The ruling: The majority finds that forcing states to create their own health insurance exchanges at the risk of their residents losing subsidies is improper coercion.

The argument: Without the subsidies, a state’s health insurance market would fall into a “death spiral.” That means the law would effectively force states to build one.

Why they would do it: In its last decision, the court overturned a part of the law forcing states to expand Medicaid, saying it was coercive. Justice Anthony Kennedy seemed open to that logic again.

Why they wouldn’t do it: It’s a constitutional argument, which is a bigger deal than for the justices to simply interpret the law’s wording.

The ‘Not Our Problem’

The ruling: The majority finds that the law is poorly written but needs to be interpreted strictly, essentially saying the court’s hands are tied.

The argument: Congress didn’t do its job well when it passed the final version of the bill, but it’s not up to the White House — or the court, for that matter — to fix it.

Why they would do it: The Supreme Court regularly throws laws back to Congress to fix. They’ve done it recently it with a fair pay law, the Voting Rights Act and campaign finance law.

Why they wouldn’t do it: Precedent. In the most-cited administrative law case in history, the Supreme Court found that the White House should have leeway to interpret poorly worded laws.

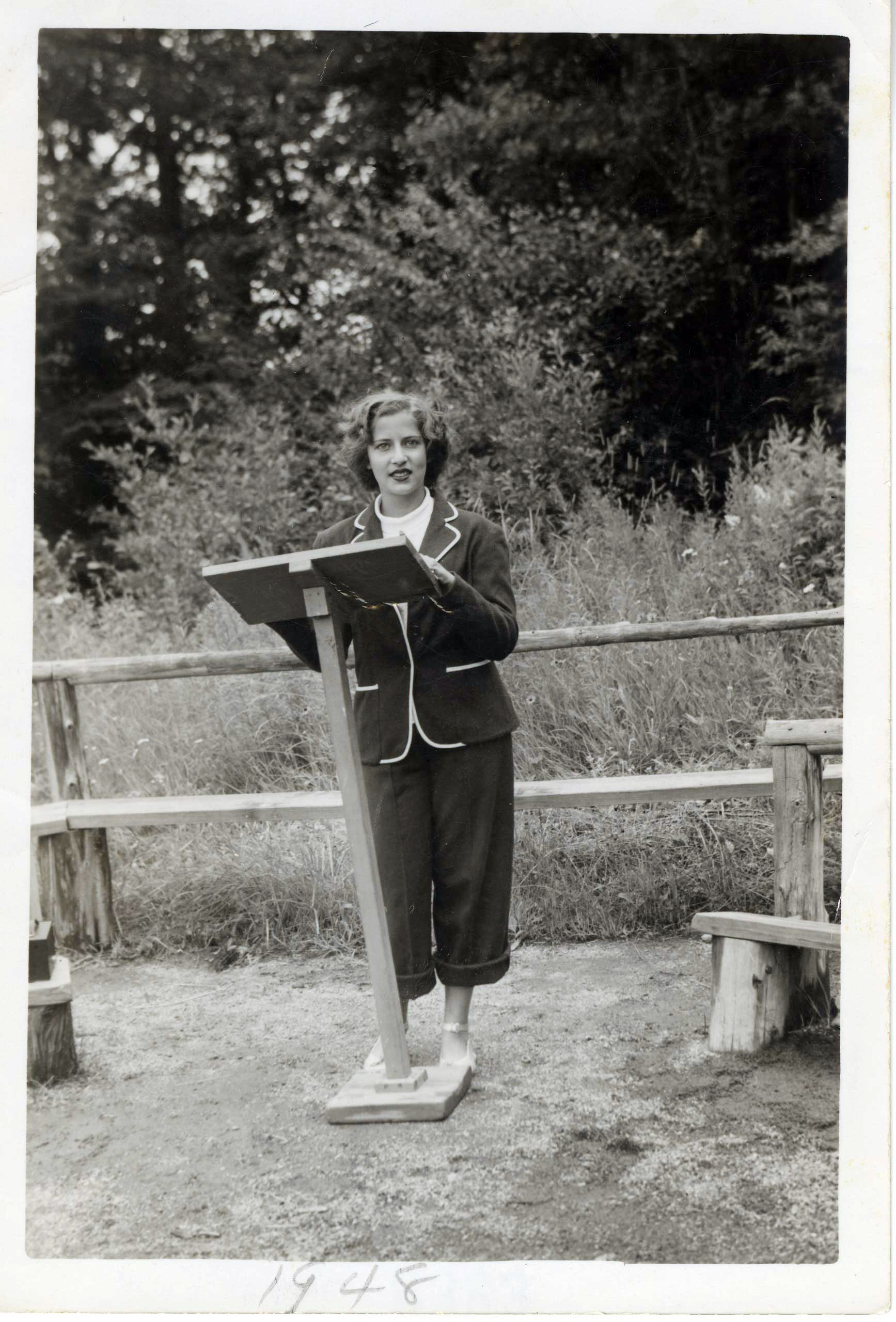

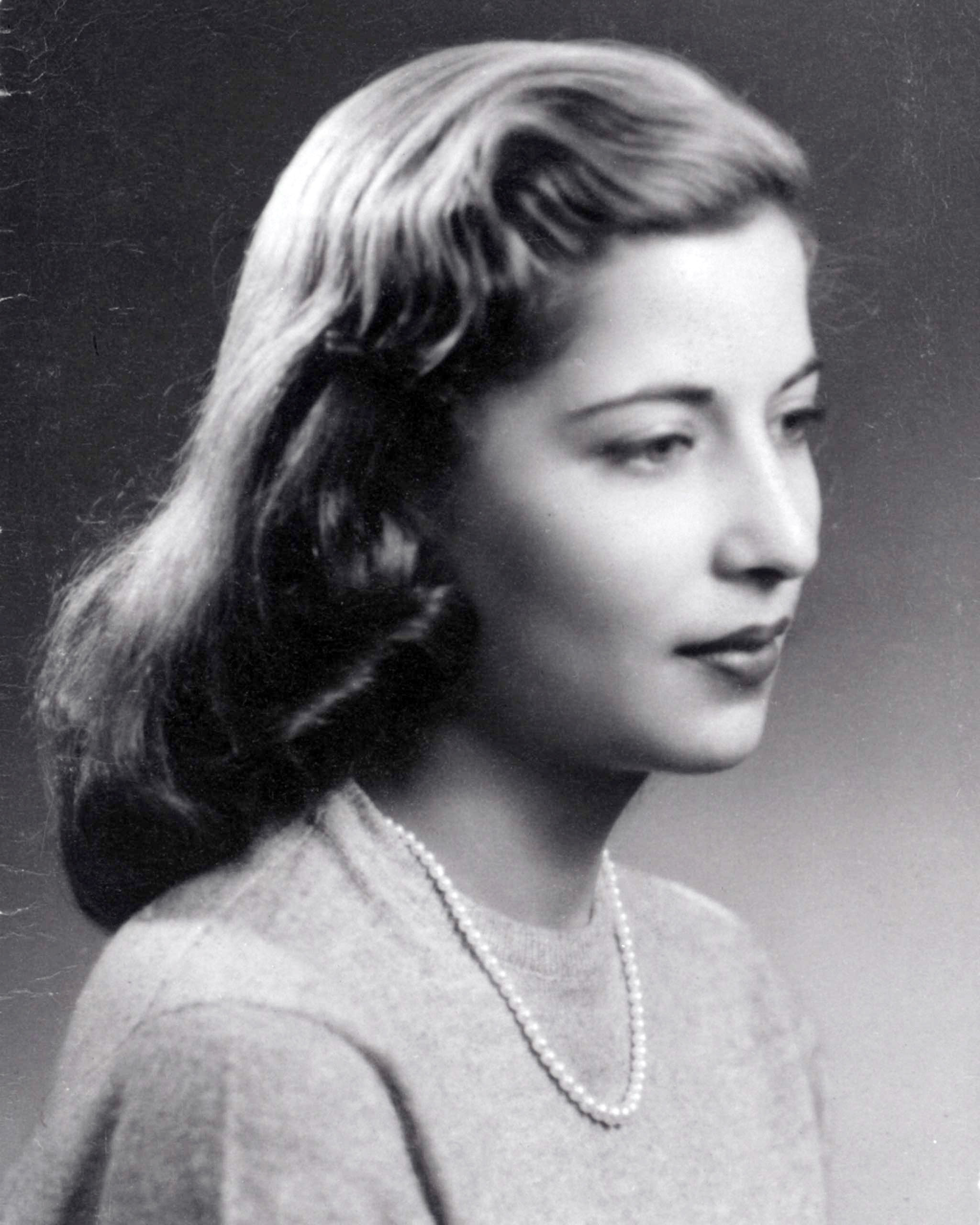

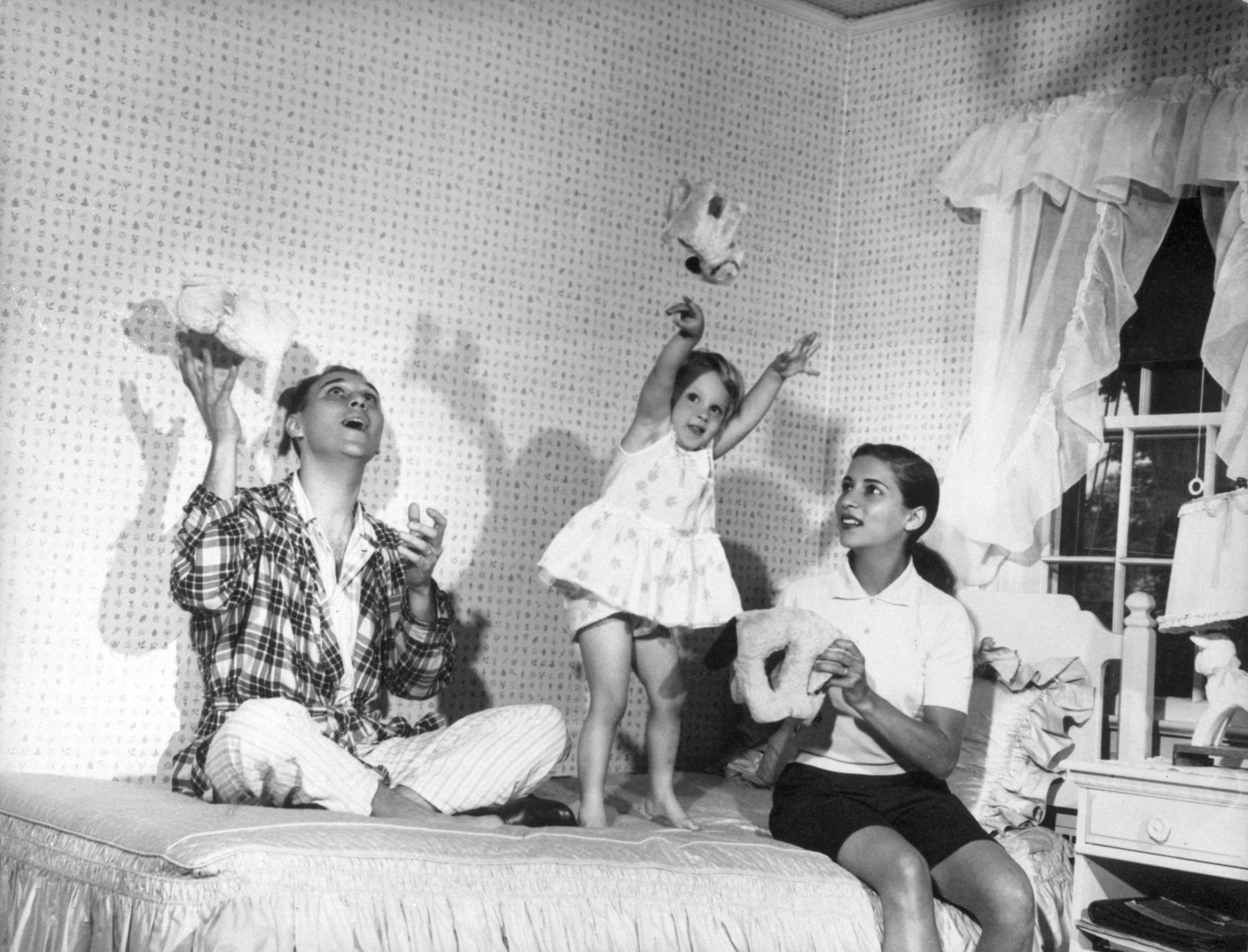

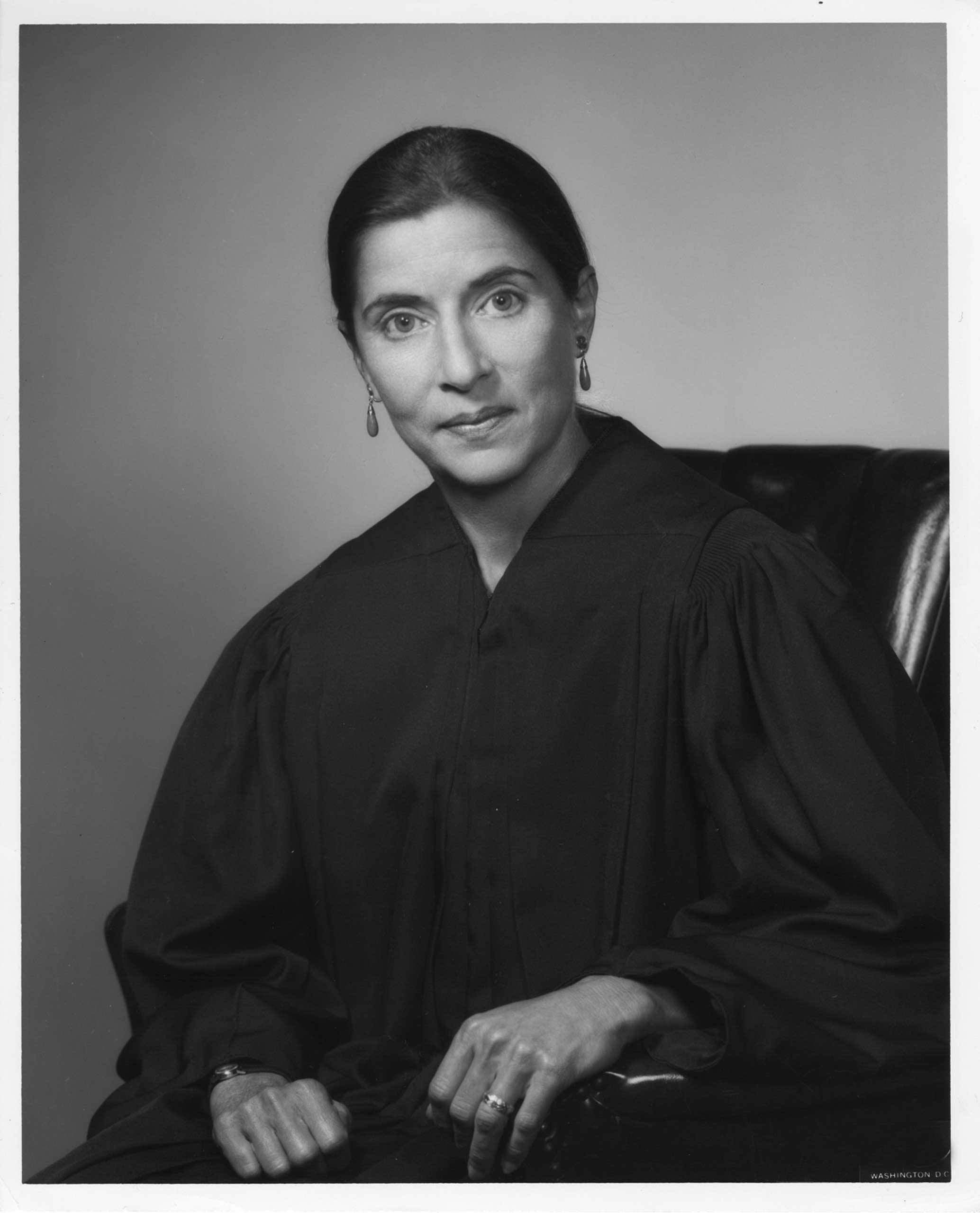

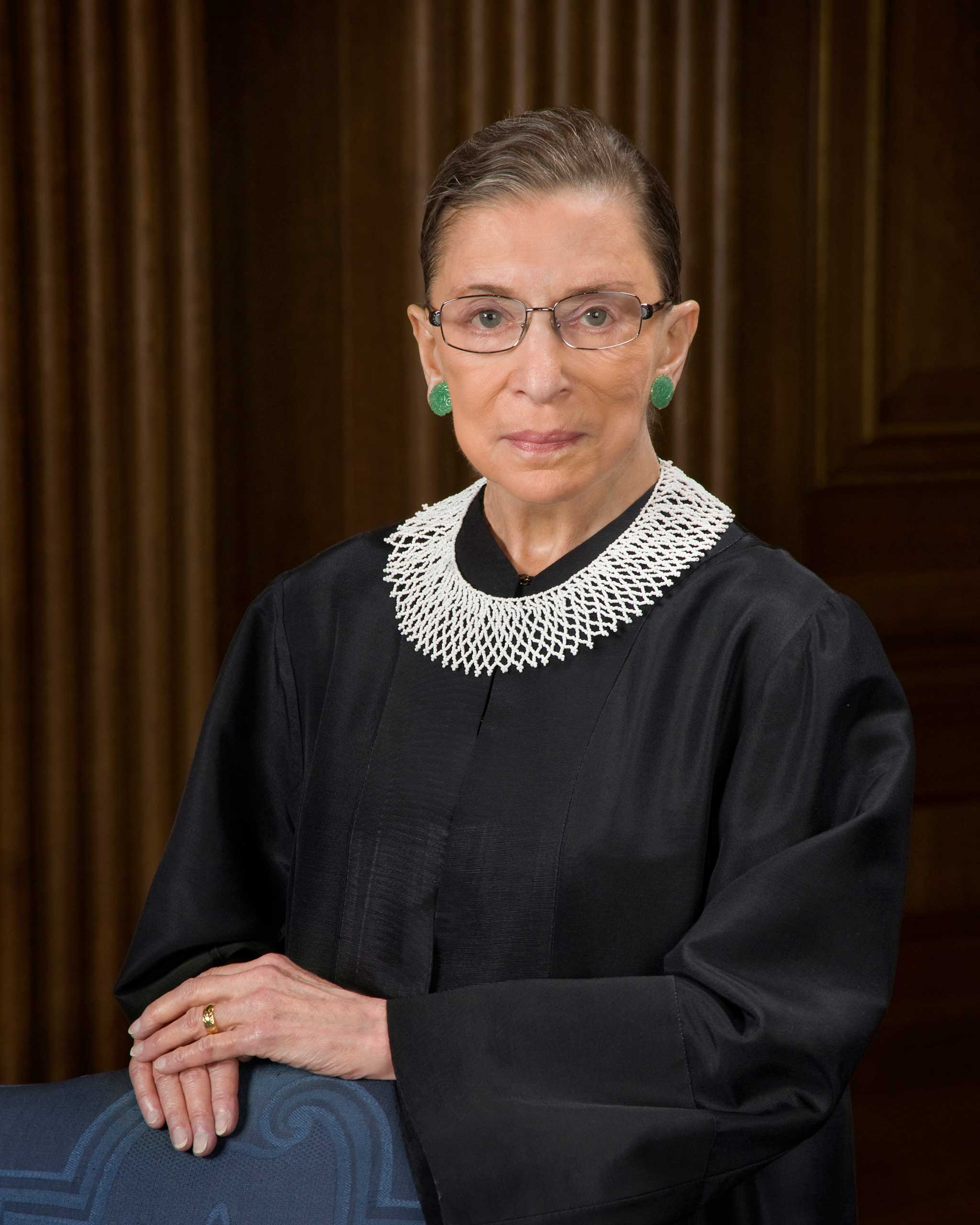

See Ruth Bader Ginsburg Grow from Toddler to Supreme Court Justice

The Conservative Hail Mary

The ruling: The majority finds that Congress intended for a state’s residents to be denied subsidies if the state didn’t set up its own insurance exchange.

The argument: An MIT economist who helped design the law once said that in an academic lecture that has since gone viral in conservative circles.

Why they would do it: The lawsuit’s supporters have argued that Democrats in Congress intended this all along. Going along with that argument would avoid the problem of legal precedent.

Why they wouldn’t do it: There’s lots of evidence, such as interviews with the staffers who actually wrote the law, that Congress didn’t intend this. It’s a longshot.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com