No one sets the table better than Benjamin Netanyahu. With Ehud Barak, his defense minister at the time, the Israeli prime minister pushed the matter of Iran’s nuclear ambitions to the front of the global agenda three years ago by threatening to launch military strikes against Tehran. And he spent the last month or so — while running for re-election back in Israel, no less — stoking the keen, keen anticipation that awaited Tuesday’s joint address to Congress.

By the time he took the rostrum in the House at ten minutes after 11, the drumroll was almost deafening; on Fox News a half hour earlier, the camera was trained on the empty hallway outside the Capitol office of Speaker John Boehner, empty of human traffic but every molecule of air charged.

So perhaps a letdown was inevitable. Going by the speech itself, though, the problem was more that Netanyahu no longer seems entirely certain what he wants, or at least how to put it. He spoke against the agreement that appears to be taking shape between Iran and six world powers, led by the United States. But at one point in the speech he seemed to concede that the agreement would go forward — calling for its final draft to include language that would extend it beyond ten years unless Iran “changes its behavior by the time the agreement expires. If Iran wants to be treated like a normal country, let it act like a normal country,” Netanyahu said.

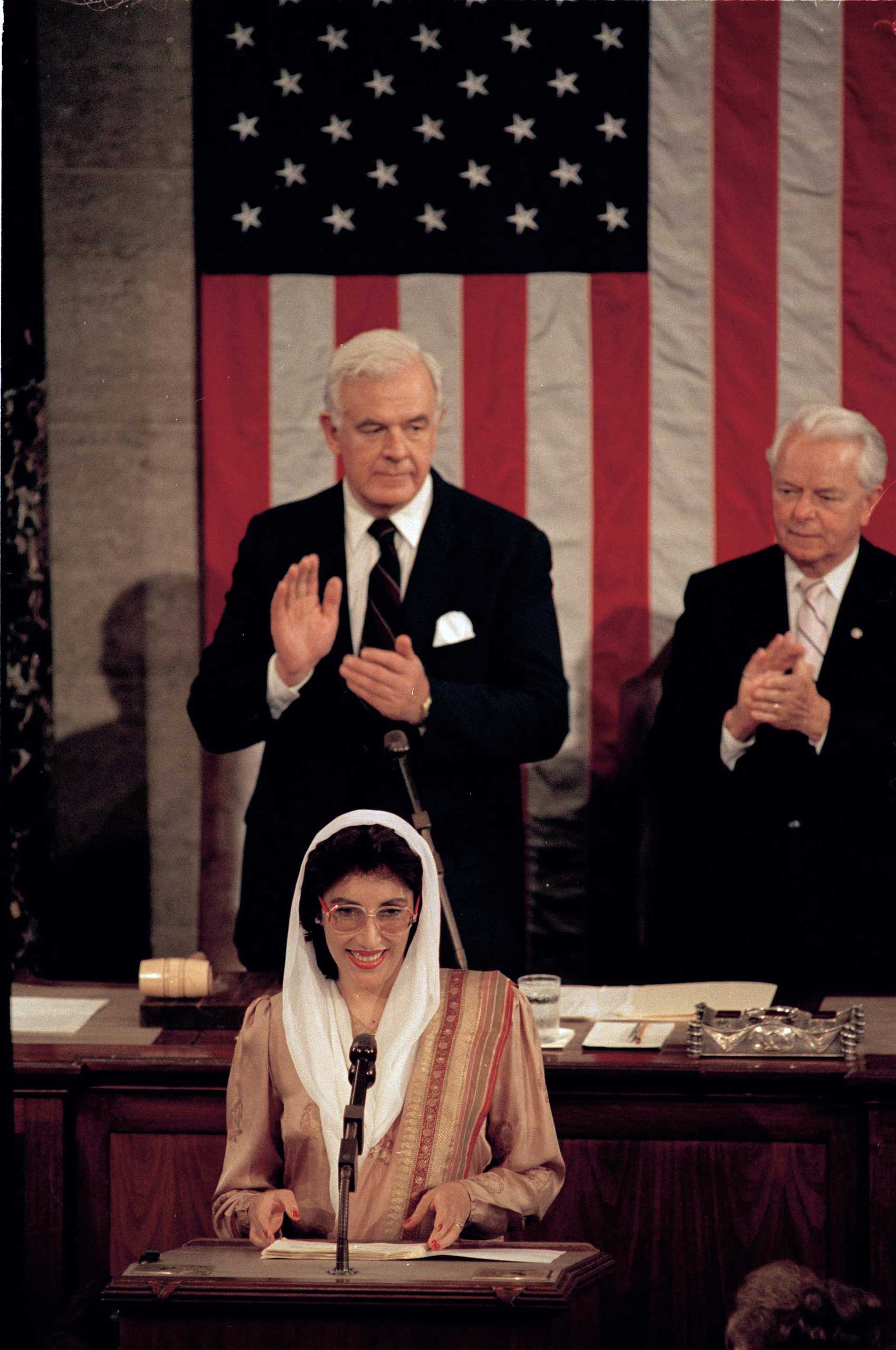

7 Times World Leaders Addressed Congress

Nor was it clear whether Netanyahu’s words were backed by the possibility of an Israel military strike, the barely veiled threat that had proved so effective in galvanizing world attention to Iran’s pursuit of the atom. Halfway through the speech, he essentially took the gun off the table by suggesting the next step would be another round of talks: “Now we’re being told, the only alternative to this deal is war,” Netanyahu said. “That’s not true. The alternative to a bad deal is a much better deal!”

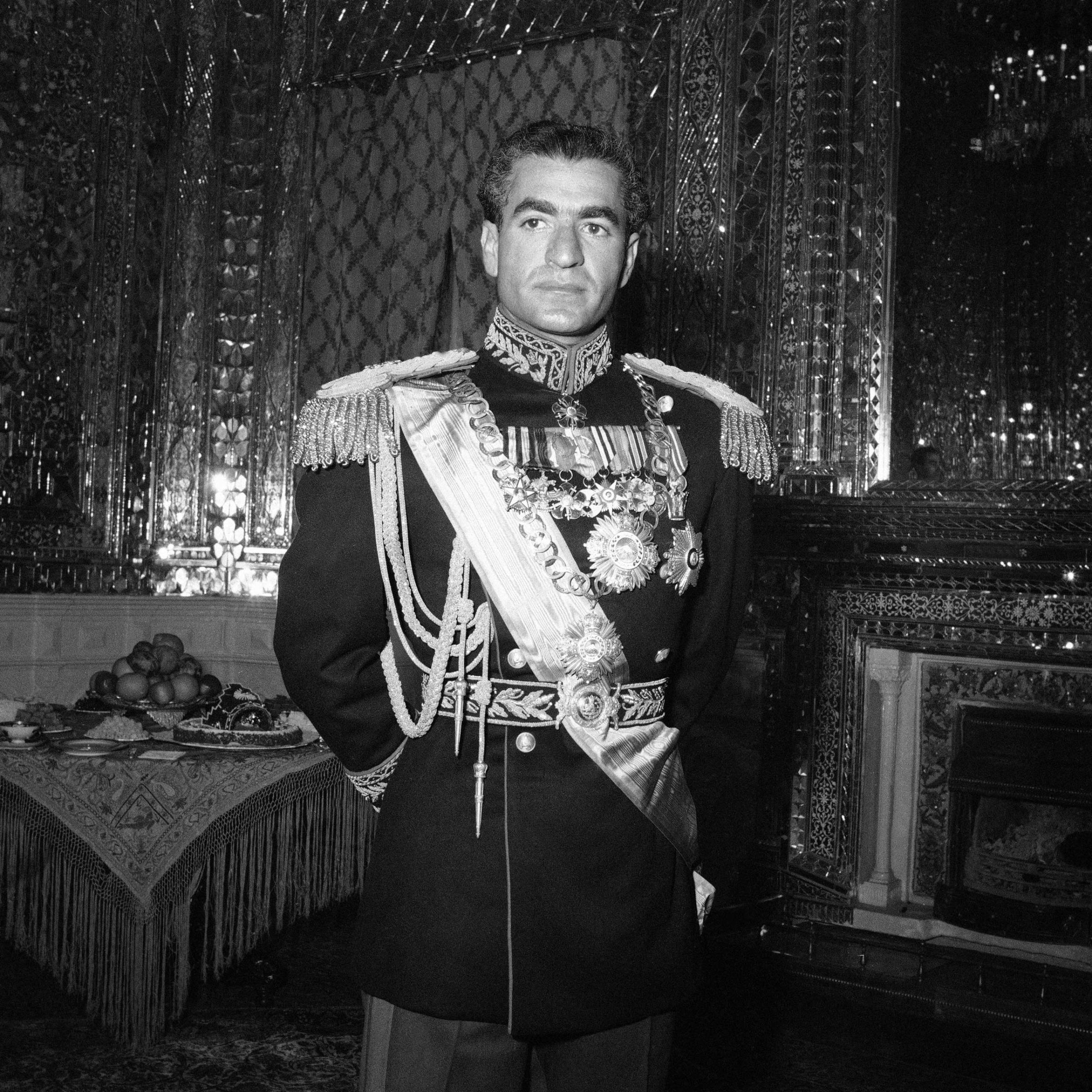

Why would that be? It turns out the country that Netanyahu passed almost all of 40 minutes describing as single-mindedly obsessed with achieving nuclear weapons, may, he said, want something else as well: “If Iran threatens to walk away form the deal – and this often happens in a Persian bazaar — call their bluff. Because they need the deal a lot more than you do.”

The observation, puzzling only in the context of the speech, may well be correct. Even before plummeting oil prices delivered another staggering blow to the petroleum exporter, Iran’s economy was crippled by the array of economic sanctions that President Obama rallied world powers to impose on Tehran (operating on the logic that peaceful coercion was better than the military option Israel appeared poised to exercise). The problem is that Israel no longer appears poised to launch air strikes, yet its leader appears trapped in the rhetoric that made the threat of them credible. It’s a binary equation, where Netanyahu reliably offers the negative to whatever the question at hand: warning that sanctions won’t work, then that they must be left in place, that an interim agreement must be avoided lest it become permanent, then that talks continue beyond the March deadline both sides say they want to honor.

MORE: Why Bibi and Barack Can’t Get Along

It’s a rhetorical trope that may or may not become a trap, but certainly becomes predictable, which in speeches may be as bad. As the prime minister’s address wore on, the applause in the chamber appeared to drift into the dutiful.

Only when he turned to the Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel (the Holocaust survivor Netanyahu tried in vain to persuade to run for the largely ceremonial office of Israel’s President) did the response reach the tumult that greeted his March 24, 2011, address, a frankly cocky appearance that cemented Netanyahu’s mastery of The Hill.

The Wiesel introduction came amid the customary expression of defiance — “Never again” — and vow that Israel would protect itself, which Netanyahu immediately walked back with the observation that the United States of course could be counted upon to do the same. Left unsaid, as always, amid the talk of an existential threats is the matter of Israel’s own nuclear arsenal, and its refusal to sign the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty that is providing so much leverage against signatory Iran.

Speeches may be what the man does best; Netanyahu cut his teeth in politics as Israel’s videogenic spokesman in America, where he attended high school and college, and Hebrew-speakers say he is every bit as effective in that language. But having assigned himself the mission of derailing the negotiations he had basically set in place, then warned against, then said must continue, Netanyahu had to thread a needle, and could not help ending up in a bit of a snarl.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com